-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2015; 5(4): 169-177

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150504.05

Anxiety as a Predictor of Academic Achievement of Students with Learning Difficulties

Mahfouz Abdelsattar Abuelfadl

Associate Professor of Mental Hygiene, Hurghada Faculty of Education, South Valley University

Correspondence to: Mahfouz Abdelsattar Abuelfadl, Associate Professor of Mental Hygiene, Hurghada Faculty of Education, South Valley University.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The current study investigates the relationship between foreign language anxiety (FLA) and academic achievement of LD pupils in Kuwait. Two main tools have been used; Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) (Horwitz et al., 1986) and a standardized achievement test in English. Results revealed that there is a positive correlation between anxiety and academic achievement. Also, it was shown that females are more anxious than their male counterparts. It is recommended that more studies should be directed to the field of anxiety in the field of learning difficulties.

Keywords: Anxiety, Academic achievement, LD

Cite this paper: Mahfouz Abdelsattar Abuelfadl, Anxiety as a Predictor of Academic Achievement of Students with Learning Difficulties, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 169-177. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150504.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Introducing the Problem

- Researching foreign language anxiety is itself a complex process that could be caused by multiple factors, such as competition, real difficulties in language processing and production, personal and interpersonal anxieties and beliefs, and also because foreign language learning can challenge the self-concept of the learner, so foreign language learning anxiety cannot be studies in isolation. MacIntyre and Gardner (1994:2) report that understanding the mechanism of anxiety in language learning has been of major concern to educators and researchers. Since its emergence in the 1970s, research in affective variables of Second/Foreign language learning has caught increasing attention in the third millennium (Liu, 2006; Cheng, Howritz & Schallert, 1999; Howritz, 1995; Howritz, Howritz & Cope, 1986). Foreign language scholars, teachers and learners have long been interested in identifying variables that affect foreign language learning (Adeel, 2011). Foreign language learning is affected by certain factors; one of the top factors affecting language learner process is the affective factor. (Salem & Abu Al Dyiar, 2014). Hence, there are three affective variables are argued to influence foreign language learning; attitude, motivation and anxiety.

1.2. Literature Review and Related Studies

- Foreign language anxiety has become a great concern in foreign and second language research over the last three decades (Trang, 2012, p.69) due to the specific nature of foreign language and the amount of fear and apprehension relate to learning such languages (Horwitz. Horwitz, and Cope 1986). In general academic anxiety can be defined as "a unifying formulation for the collection of anxieties learners experience while in schools" (Cassady, 2010, p.1). Also, Zhang (2001) defined anxiety as "the psychological tension that the learner goes through in performing a learning task". Moreover, Scovel (1978, p. 134) defined anxiety as "a state of the individual when he/she feels uneasiness, frustration, self-doubt, apprehension, or worry." Specifically, foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) is defined as "a distinct complex construct of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of language learning process (Horwitz. Horwitz, and Cope 1986, p.128), it has also been defined as "a phenomenon related to but distinguishable from other specific anxieties." Clement (1980) defined FLA as a " complex construct that deals with learner's psychology in terms of their feelings, self-esteem, and self-confidence." On a related context, MacIntyre, (1994b, 1999) defined it as "a feeling of tension and apprehension specifically associated with second or foreign language contexts, including speaking, listening, and learning, or the worry and negative emotional reaction arousal when learning or using a second or foreign language.Abu-Rabia (2004: 711) defined anxiety as fear, panic, and worry". Anxiety is divided into three different types:1. Trait anxiety, which is a personality trait (Eysenck, 1979)2. State anxiety, which is apprehension experienced at a particular moment in time.3. Situational anxiety, which is anxiety experienced in a well-defined situation (MacIntyre & Gardner, 1991a).According to Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986), there is a unique type of anxiety that is specific to foreign language which is originated form a situation-specific anxiety. This coincides with the results of Chen and Chang (2004) study as it found that academic learning history as well as test characteristics was not predictive variables of foreign language anxiety. Young (1986) found no relationship between state anxiety and oral proficiency in French, German and Spanish when students' ability was controlled. Chastain (1975) concurrently found positive, negative, and near zero correlations between anxiety and French, German and Spanish second language learning. While finding a negative correlation between French students' scores on tests and anxiety, Chastain also discovered a positive correlation between anxiety and the scores of German and Spanish students. Traditionally, anxiety research has focused mainly on the state-trait anxiety in investigating the role of anxiety in language learning. According to such an approach, language anxiety is a transfer of other more general types of anxiety. Therefore, test- anxious students feel so because they fell that they are constantly tested. Also, shy people feel uncomfortable when asked to communicate publicly. Early studies adopting such approach yielded conflicting results about the effects of anxiety on achievement and performance. (Trang, 2012, p.70)Studying foreign language anxiety not only "contributes to our understanding language achievement, but it also it is fundamental to our understanding of how learners approach language learning, their expectations of success or failure, and ultimately why the continue or discontinue study" (Horwitz, 2001, p.122). FLA has adverse impact on students' performance; it has more potential for embarrassing themselves, frustrating their self-expression, and challenging their self-esteem and sense of identity than almost any other learning activities (MacIntyre, 1999, p.33). It goes without saying that anxiety arousal could act as a causal agent that produces individual differences in foreign language learning. Hence, high-achievers might "freeze up" on a test; anxiety is more to be likely a cause rather than a consequence of poor performance. (Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope, 1986, MacIntyre, 1995b). On the contrary, Sparks and Ganschow (1995) inquire whether language difficulty causes anxiety or anxiety causes the language anxiety. In various researches, Sparks and Ganschow (1991, 1993a, 1993b, 2007) report that it is doubtful to assure the importance attributed to FLA in learning the foreign language. According to MacIntyre (1995a), the relationship between anxiety and task performance is cyclical one, each construct leads to the other.Foreign language anxiety is closely associated with problems in language learning such as deficits in listening comprehension, reduced word production, impaired vocabulary learning, lower grades in language courses, and lower scores on standardized tests (Howritz and Young, 1991). In spite of the great amount of research in the field of foreign language anxiety has not yielded a clear-cut relationship between anxiety and foreign language achievement (Scovel, 1978). One of the studies is the one conducted by Awan et al., (2010) who investigated foreign language classroom anxiety in its relationship with students' achievement. It is revealed that language anxiety and achievement are negatively related to each other. It is also found that female students are less anxious in learning English as a foreign language than male students. Speaking in front of others is rated as the biggest cause of anxiety followed by "worries about grammatical mistakes", pronunciation and "being unable to talk spontaneously". In addition, Dordinejad and Ahmadabad (2014) investigated the relationship between foreign language classroom anxiety and English language achievement among male and female high school third-graders in Iran. Foreign language classroom anxiety was found to be significantly and negatively correlated with English language achievement. Females were found to be more anxious than their male counterparts. There are certain factors that can alleviate anxiety inside the classroom especially in foreign language learning contexts, among such factors are the learning strategies followed by learners and teaching strategies used by teachers. Therefore, Wei (2007) has drawn attention to how language learning contexts particularly affect anxiety arousal. Kondo and Ying-Ling (2004) reported 70 basic tactics for coping with language anxiety that cohered into five strategy categories: Preparation (e.g. studying hard, trying to obtain good summaries of lecture notes), Relaxation (e.g. taking a deep breath, trying to be calm), Positive Thinking (e.g. imagining oneself giving a great performance, trying to enjoy the tension), Peer seeking (e.g. looking for others who are having difficulty controlling their anxiety, asking other students if they understand the class), and Resignation (e.g. giving up, sleeping in class). According to Hembree (1988, p. 67), anxiety remediation has intensely focused on cognitive, affective, and behavioral approaches. According to Awan et al., (2010) foreign language classroom anxiety can be alleviated through producing an encouraging and motivating classroom environment. Also, teachers need to deal with anxiety- provoking situations carefully.Researching anxiety is of paramount importance for all students in all educational stages. Anxiety for students with learning difficulties is also important. Alleviating anxiety of students with learning difficulties undoubtedly helps them achieving better in academic performance. According to Carnine, Jitendra, & Silbert (1997), individuals with learning difficulties may not be intellectually impaired; rather, they suffer from learning problems as a result of an inadequate design of instruction in curricular materials (p.3).Learning difficulties refers to two main types of problems that adversely affect Students' learning. These types of problems vary according to the origin of such difficulty; learning difficulties are situated outside the child whereas learning disabilities are situated in the child's own cognitive development. (Dumont, 1994)

1.3. Questions of the Study

- The present study addressed three main questions: 1. Are there statistically significant differences between the mean scores of LD students in foreign language anxiety and academic achievement in English?2. Are there statistically significant differences between the mean scores of male and female LD students in foreign language anxiety?3. Are there statistically significant differences between the mean scores of LD students in foreign language anxiety based on their age level/grade?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

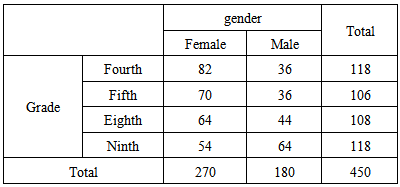

- A total of 450 students with learning difficulties in the mainstream schools in the State of Kuwait. Those students were selected from four main grades; fourth, fifth, eighth and ninth grade. The participants consisted of 118 fourth grade (82 females, 36 males), 106 fifth grade (70 females, 36 males), 108 eighth grade (64 females, 44 males), and 118 ninth grade (54 females, 64 males). The students' English language proficiency level is very high compared with their learning difficulties. Students' ages ranged from 9 to 13. The classes were dominated by female students, with a male-female ratio of 180:270 ( see table 1).

|

2.2. Materials

- Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) (Horwitz et al., 1986) was used to assess students degree of anxiety when learning English as a foreign language inside the classroom in terms of three subscales; communication apprehension, fear of negative evaluation, and state anxiety. The FLCAS consisted of 33 items that were designed on a five-point Likert Scale, ranging from "strongly agree" to" strongly disagree". In order to ensure accurate responses on the scale, an Arabic-translation of FLCAS was provided to the participants. A standardized test in English language as a foreign language was designed and displayed to jury members in the field of language testing to be sure of its reliability and validity. The total score of such a test is 60 points.

2.3. Procedures

- The FLCAS as well as achievement test were administered in the second semester of 2015. Students were asked to respond to the FLCAS questionnaire accurately and to ask their teacher once they encountered difficulties in understanding the scale items. After excluding students who did not fill in the questionnaire thoroughly and considered "drop out". The number of dropped out students was not large as the percentage of drop out students was 2.5%. Data collection was for the most part successful for each target group, with 97.8% of the fourth grade, 96.2 of the fifth grade, 95.3% of the eighth grade, and 94.9 of the ninth grade.

2.4. Data Analysis

- The reliability of the two instruments was determined using Cronbach's α. And a principle component analysis was carried out to analyze construct validity. Also, independent group t-test as well as Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to assess the differences between mean scores. An α level of 0.05 was set for all statistical procedures.

3. Results

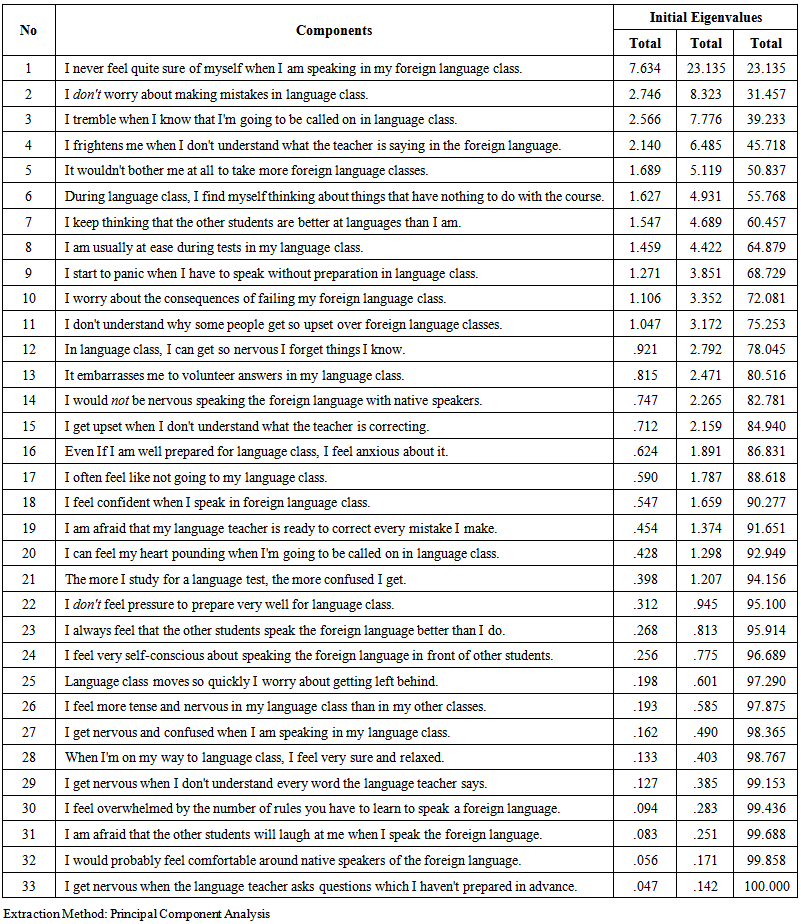

3.1. Reliability of the FLCAS and the Achievement Test

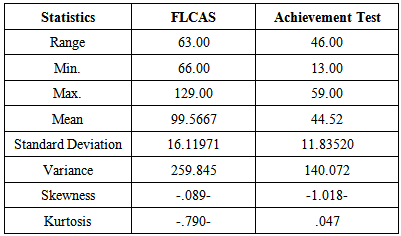

- Internal consistency was computed for each of the two main scales. Cronbach's alpha for the FLCAS was 0.81 (N = 450, M = 99.57, and S.D. = 16.119) and the Cronbach's alpha for the achievement test was 0.43 (N = 450, M = 44.52, S.D. = 11.84). Kurtosis and skewness help determine whether a distribution is not normal, and here kuetosis was -0.790 and normal for the achievement test 0.047 and the skewness was -0.089 for FLCAS and -1.018 for the achievement test. Indicating that it is not normal for FLCAS and normal for the achievement test. See Table 2 for descriptive statistics of the FLCAS and achievement test.

|

|

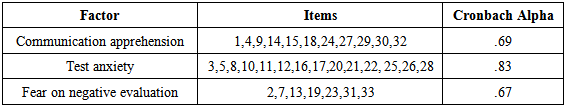

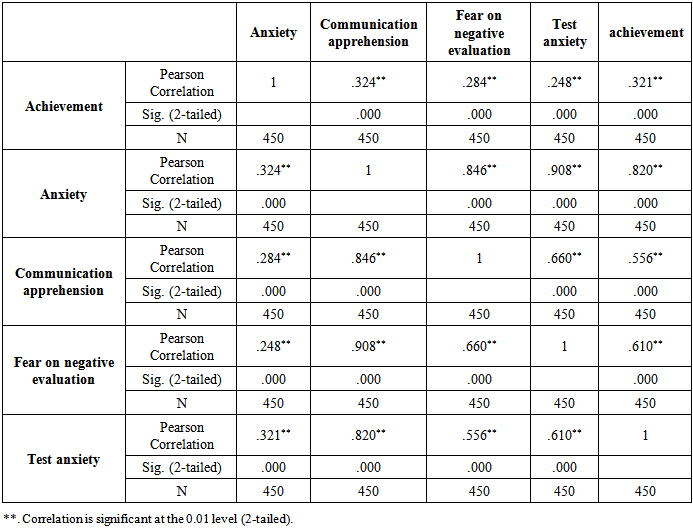

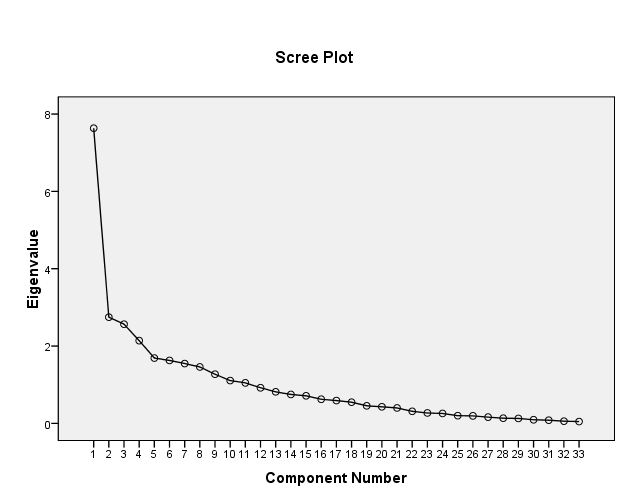

3.1.1. Principle Component Analysis of the FLCAS

- A principle component analysis with varimax rotation produced eleven factors with eigenvalues greater than one. To retain all eleven factors would create a model too complex for our purposes, consequently a smaller number of factors was extracted. Close inspection of scree plot of the eigenvalues for this study showed that the plot turned left following factor two. The last four factors were then discarded based on low factor loadings and communalities. The study is based on the single factor loading as the first factor represents 30.7% of the variance included items related to anxiety, fear, and pressure related to performance in the English classroom. See Table 4 for details of each factor.

| Table 4. Results of factor analysis for FLCAS |

3.1.2. Sampling Subjects

- The factors emerging from factor analysis are affected by subjects. The homogeneity of the subjects is assured through the factor loadings. Since we are trying to investigate the anxiety in relation to academic achievement, decision was made to pool all participants together for the factor analysis. It is clear that homogeneous samples lower variance and, consequently, factor loadings. (Matsuda and Gobel, 2004). See figure 1 for scree plot of the factor analysis.

| Figure 1. Scree plot of the factor analysis |

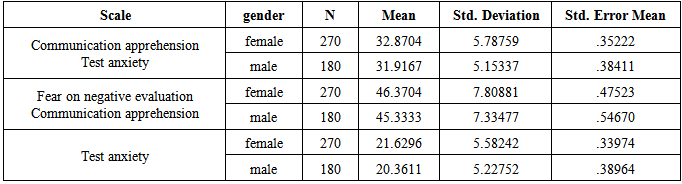

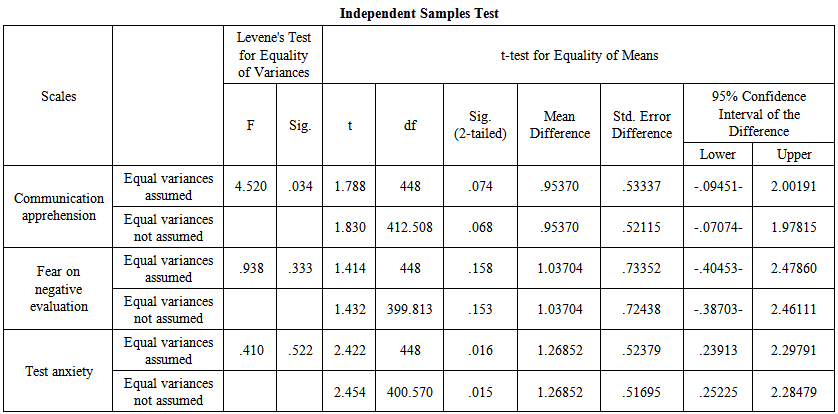

3.2. T-test

- A gender-based independent samples t-test was calculated in order to assess the significance of differences between students' responses on FLCAS and their scores on achievement test. Close inspection of Table revealed that female students have higher levels of anxiety than their male counterparts. See Table for descriptive statistics of anxiety subscales based on gender.

|

| Table 6. Independent samples t-test |

3.3. ANOVA

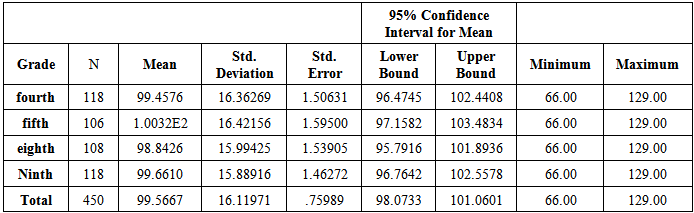

- One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the anxiety scores of the LD students in four different-staged groups; the fourth, fifth, eighth and ninth grades. See Table 7 for descriptive statistics of ANOVA (anxiety based on grade).

|

|

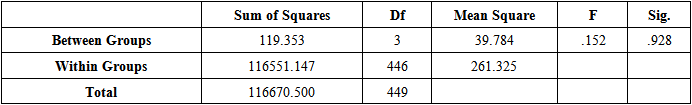

3.4. Correlation

- Bivariate correlation coefficients were conducted to assess the correlation between anxiety students experience and the students' performance in English language. The participants' levels of foreign language classroom anxiety were determined after consulting Horwitz, the developer of FLCAS and calculating the mean score of FLCAS as 99.56 (total FLCAS divide on the number of items, 33). In order to explore the relationship between foreign language classroom anxiety and English achievement, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients was run to answer whether statistically significant relationship existed between foreign language classroom anxiety and achievement. The results from Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients between FLCAS scores and English scores are exemplified in Table 9.

|

4. Discussion

- The findings of the study are not consistent or in line with the literature reviewed except for that females are more anxious than their male counterparts. Almost all studies reviewed have shown that foreign language anxiety was found to be significantly and negatively correlated with English achievement such as the studies of Dordinejad and Ahmadabad (2014) and Awan et al., (2010), Gardner (1997), Horwitz (2001), Park and Lee (2005), Liu (2006), and Atasheneh & Izadi (2012). In contrast with the results of the previous studies, findings of the current study revealed that there is a positive correlation between anxiety and academic achievement. This means that the more anxiety LD students have the higher scores they achieve. This may be explained as we were dealing with exceptional sample of students. Students without learning difficulties do their best to achieve their academic goals to satisfy their parents. Motivation lays behind exerting much effort to achieve academic goals which subsequently results in anxiety symptoms. According to Waseem and Jibeen (2013), instrumental motivation is a significant contributor towards second language anxiety, including fear of negative evaluation, speech apprehension, fear of tests and anxiety of English classes, whereas integrative motivation only contributed towards fear of negative evaluation. This coincides with other studies results that revealed that more instrumental motivation than integrative motivation in situations where English is a perquisite for progress and economic benefits.Another astonishing point about results obtained from the study us that there are no statistically significant differences in the scores of participants based on the age/grade factor. Students with learning difficulties have the same symptoms of difficulties even though they are of different age. However, in accordance with literature reviewed females are found to be more anxious than males based on their self-report responses in the FLCAS. It is argued that gender played an important role in students' classroom performance (Matsuda & Gobel, 2004).

5. Implications

- Results of the study have revealed that LD students are of special nature. Those students have distinguished psychological characteristics compared with normal students at the same age. Thus, it is recommended that more studies should be directed to the field of anxiety in the field of learning difficulties.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML