-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2015; 5(2): 98-107

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150502.07

A Cross Cultural Comparison of Disability and Symptomatology Associated with CFS

Maria Zdunek1, Leonard A. Jason1, Meredyth Evans1, Rachel Jantke1, Julia L. Newton2

1Center for Community Research, DePaul University, Chicago, USA

2Institute for Ageing and Health, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Correspondence to: Maria Zdunek, Center for Community Research, DePaul University, Chicago, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Few studies have compared symptomatology and functional differences experienced by patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) across cultures. The current study compared patients with CFS from the United States (US) to those from the United Kingdom (UK) across areas of functioning, symptomatology, and illness onset characteristics. Individuals in each sample met criteria for CFS as defined by Fukuda et al. (1994). These samples were compared on two measures of disability and impairment, the DePaul Symptom Questionnarie (DSQ) and the Medical outcomes study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Results revealed that the UK sample was significantly more impaired in terms of mental health and role emotional functioning, as well as specific symptoms of pain, neurocognitive difficulties, and immune manifestations. In addition, the UK sample was more likely to be working rather than on disability. Individuals in the US sample reported more difficulties falling asleep, more frequently reported experiencing a sudden illness onset (within 24 hours), and more often reported that the cause of illness was primarily due to physical causes. These findings suggest that there may be important differences in illness characteristics across individuals with CFS in the US and the UK, and this has implications for the comparability of research findings across these two countries.

Keywords: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), Cross Cultural Comparison, United States, United Kingdom, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)

Cite this paper: Maria Zdunek, Leonard A. Jason, Meredyth Evans, Rachel Jantke, Julia L. Newton, A Cross Cultural Comparison of Disability and Symptomatology Associated with CFS, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 98-107. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150502.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is highly debilitating and affects individuals across different cultures and countries [11]. Individuals with CFS often experience multiple symptoms including post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and memory problems [5].Within the United States (US), the earliest prevalence estimates of CFS published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ranged from .002% to .0073% [6]. Following these early estimates, Jason et al. [12] calculated a prevalence estimate of .42% utilizing a randomized community based sample. Another community-based study by the CDC indicated an estimated prevalence of .24% [22] but estimates by the CDC have been as high as 2.54% [21]. Within the United Kingdom (UK), estimates of prevalence have also been variable, ranging from .2% [19] to 2.6% [25]. One possible reason for the variability in prevalence estimates for both countries is the use of different ways of operationalizing case definitions to select participants with the illness. For example, in the study by Jason et al. [12], which found a prevalence rate of .42%, the Fukuda et al. [5] case definition was used to screen individuals for the illness, whereas Reeves et al. [21] found a prevalence rate of 2.54% when using an operationalized CFS case definition. In terms of the UK prevalence studies, Nacul et al. [19] estimated a prevalence of .19% when using only the Fukuda et al. [5] criteria and a prevalence of .11% when only using the Canadian Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Clinical Case criteria (CCC) [2]. Wessely et al. [25] estimated the prevalence of CFS as 2.6% when using the Fukuda et al. [5] criteria, a prevalence of 2.2% when using the Oxford [23] criteria, a prevalence of 1.2% when using the Holmes et al. [8] criteria, and a prevalence of 1.4% when using the Lloyd, Wakefield, Boughton, and Dwyer [16] criteria. The variety of case definitions used in research studies, as well as differences in how case definitions are operationalized can lead to considerable heterogeneity among individuals and different prevalence rates across study samples. Additionally, the use of varying case definitions can create problems when trying to make cross-cultural comparisons of CFS on variables such as socio-demographic characteristics, symptoms, and impairment level. Such issues could make it hard to determine whether differences across cultures are due to the case definitions used to select samples or true differences across the samples. For example, in one study among severely impaired individuals with CFS who were referred to clinics in Germany, the UK, and the US, no significant differences in impairment levels were found [7]. This study was limited in that the clinics in each country used a variety of case definitions to select participants, with the US clinic using the Fukuda et al. [5] criteria, the UK clinic using the Oxford criteria [21] and the Germany clinic using the Holmes et al. [8] case definition. Though Hardt et al. [7] indicated that the “majority” of the UK sample and 83% of the German sample met Fukuda et al. [5] criteria, it is unclear whether the lack of differences were truly representative of the samples or resulted from the three different case definitions used to select participants. In a similar study, individuals from eight clinics in the UK, US, and Australia completed a self-report questionnaire that assessed for the presence, severity, and frequency of CFS symptoms, cause of illness onset, sudden or gradual mode of illness onset, and general health symptoms [27]. The results revealed that there were no significant differences across the centers or countries on any items of the measure. However, Wilson et al. [27] also used multiple case definitions to select participants: two centers used the Fukuda et al. [5] definition, two used the Holmes et al. [8] criteria, two used the Oxford [23] criteria, and two used Lloyd et al. [16] criteria. In preparation for a meeting of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a survey was conducted that involved a large sample of individuals from around the world who self-reported as having a diagnosis of CFS, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), or ME/CFS (L. Chu, personal communication, March, 2013). Results of the survey revealed the US sample was significantly older and had a longer illness length. Individuals in the UK sample reported significantly more impairment with regard to physical functioning, and more frequently described their activity level on their “best days” as bedridden. The participants all self-identified as having either a CFS, ME, or ME/CFS diagnosis, but it cannot be assumed that participants were diagnosed with the same case definition. Even with this limitation, these findings suggest there are potential key differences across the samples of patients from the US and UK, with regard to age, illness length, and impairment level. Recently, Jason, Brown, Evans, Sunnquist, and Newton [10] used the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ) to compare three samples of individuals on the criteria for two different case definitions: the CFS Fukuda et al. [5] case criteria and the CCC [2]. Of the three sample populations, two were US based and one was UK based. The results of the study revealed that 96.3% and 92.6% of the two US based samples met the CFS Fukuda et al. [5] criteria compared to 86.5% of the UK sample. Furthermore, 77.2% and 72.7% of the two US based samples compared to 72.9% of the UK sample met the CCC [2]. Jason, Sunnquist, Brown, Evans, and Newton [14] also compared the same US based sample and a UK sample using the Myalgic Encephalomyelitis International Case Criteria (ME-ICC) [2] and found that a comparable percentage in both the US based and UK based samples met the ME-ICC (57.1% and 58.3%, respectively). This suggests that differing criteria may include distinct percentages of individuals from the US and the UK. More research is necessary to examine possible differences between individuals with CFS in the US and the UK, when using one uniform case definition, to eliminate possible differences from distinct criteria. Given the differences in the percentage of individuals meeting Fukuda et al. [5] case criteria across the US and UK samples, it is unclear whether there are other differences between those in the US and UK. Prior reports did not assess for possible differences across the US and UK samples diagnosed with the Fukuda et al. criteria [5] in terms of demographic information, functioning level, symptoms, and illness characteristics, but rather solely compared prevalence rates [10, 14] or assessed for symptoms and functional impairment using multiple case criteria [7, 27]. In the current study we assess, for the first time, differences on a wide variety of symptom and disability measures for individuals meeting the Fukuda et al. [5] case definition in the US and the UK. Given the contradictory results of past cross-cultural studies [7, 27] we are not able to make specific predictions, therefore, this is an exploratory study that will assess differences between a US and UK sample on symptoms, measures of functional impairment, onset, and illness characteristics.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

- Participants in the current study were derived from a US and a UK sample. The US sample, also referred to as the DePaul sample, was derived from a convenience sample of international adults who self-identified as having ME and/or CFS. International participants within the US sample were removed for the purposes of investigating a strictly US sample. The UK sample, also referred to as the Newcastle sample, was comprised of participants who were referred by primary care physicians to the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Royal Victoria Infirmary clinic in England.

2.1.1. DePaul Sample

- The US sample included adults between the ages of 18 and 65 recruited through various means, such as internet forums, and who had previously participated in studies at DePaul University. Those who were recruited self-identified as having CFS or ME and were required to provide informed consent before participation in the study. For the purpose of this study, participants were selected using the Fukuda et al. [5] criteria, removing those with exclusionary conditions (e.g. BMI > 45, lifelong fatigue, medically or psychiatrically explained fatigue), and international participants, removed for the purposes of investigating a strictly US sample.

2.1.2. Newcastle Sample

- Participants from the UK sample included adults between the ages of 18 and 75 who were identified by primary care physicians as possibly having CFS and who were referred to the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Royal Virginia Infirmary clinic for a full medical assessment. All participants were assessed by a consultant physician. The individuals, who were fully assessed and found eligible, were required to provide informed consent prior to participation in the study. For the purpose of this study, individuals were selected using the Fukuda et al. [5] criteria, removing those with exclusionary conditions (e.g. BMI > 45, lifelong fatigue, medically or psychiatrically explained fatigue).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. DePaul Symptom Questionnaire

- Participants from both samples completed the DePaul symptom questionnaire (DSQ), a self-report measure of ME, ME/CFS and CFS symptomatology that includes items which assess medical and social history. The questionnaire includes items that assess the frequency and severity of 54 symptoms related to the illness on a Likert scale of 0-4, with frequency scales of 0 = none of the time, 1 = a little of the time, 2 = about half the time, 3 = most of the time, and 4 = all of the time, and severity scales of 0 = not present, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, and 4 = very severe. A composite score of the symptoms is calculated by multiplying the frequency and severity symptom composite scores by 25 and averaging the sum, resulting in a 100-point scale. Other questions include time of onset, symptoms present before illness, diagnosis, and activity levels before and after onset. The DSQ has been found to have good test-retest reliability as a standardized method to identify individuals with CFS, ME, or ME/CFS [13]. It also has strong construct, convergent, and discriminant validity [1].

2.2.2. Medical outcomes study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36 or RAND Questionnaire)

- The SF-36 is a short form self-report measure on functional status related to health [23]. The SF-36 assesses functioning on eight subscales including domains of physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, vitality, role emotional, and mental health on a 0-100 scale, where a higher score indicates better functioning. The measure has been found to have good discriminant validity as a measure of mental health and also physical functioning, and is both psychometrically and clinically valid [18]. It has shown strong internal consistency and the ability to identify functioning for a variety of participant populations [17].

3. Results

3.1. Description of Samples

3.1.1. DePaul Sample

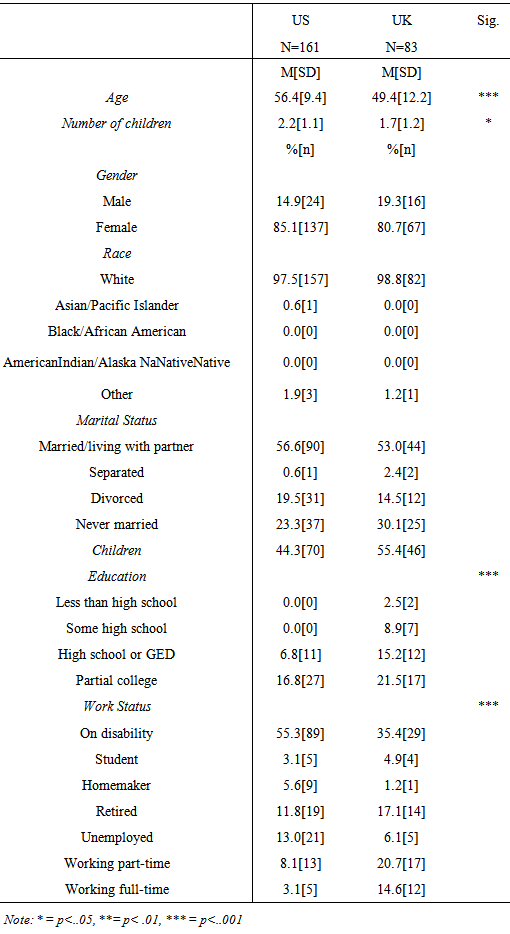

- 217 participants from the US sample completed the DSQ and a total of 162 participants were included in the current study, after participants were removed for exclusionary conditions or not meeting the Fukuda et al. [5] criteria. The mean age of the participants was 52.01 (SD=11.5). 85.1% of the participants identified as female and 14.9% identified as male. 97.5% of the sample identified as White with 1.9% identifying as Other and 0.6% as Asian/Pacific Islander. Of the sample, 56.6% of participants identified as married, 23.3% identified as never married, 19.5% identified as divorced, and 0.6% identified as separated. In terms of educational status, 39.8% of participants reported completing a graduate or professional degree, 36.6% reported completing a standard college degree, and 23.6% reported finishing high school or some college. With regards to work status, 55.3% of participants reported that they were on disability at the time of the study, and 11.2% reported working either full-time or part-time.

3.1.2. Newcastle Sample

- The UK sample was comprised of 100 participants. Data from 83 participants was used for the present study. The mean age of the 83 participants in the UK sample was 45.9 years (SD=13.6). 80.7% of the sample was female and 19.3% was male. Of the sample, 98.8% identified as White, and 1.2% identified as Other. Fifty-three percent of the sample identified as married, 30.1% identified as never married, 14.5% identified as divorced, and 2.4% identified as separated. Of the sample, 55.4% reported having children, with the mean number of children as 1.7 (SD=1.2). With regard to education level, 20.3% reported having a professional or graduate level degree, 30.4% reported having a college degree, 21.5% of participants reported having completed part of college, 26.9% reported having a high school diploma or less. In terms of work status, 35.3% reported working either full-time or part-time, and 35.4% of the UK’s sample reported being on disability.

3.2. Demographics

- Table 1 includes demographic data for the two samples. A univariate analysis of variance test revealed the average age of the US sample was significantly older than the UK sample (F(1, 242) = 13.41, p < .001) and the US sample had significantly more individuals with children than the UK (F(1,125) = 5.05, p = .026). In addition, chi-square analyses and Fisher’s exact tests revealed the US sample had a higher proportion of participants with a higher education level than the UK sample, (p < .001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) as well as a higher proportion of participants on disability than the UK sample ( p < .001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test).

|

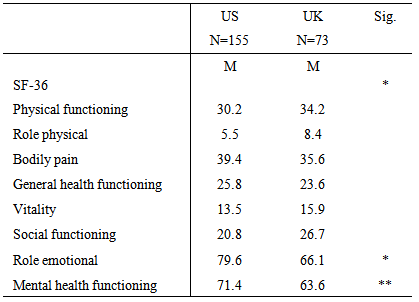

3.3. Functional Status

- Table 2 represents data from the SF-36. MANCOVA results revealed the two samples were significantly different overall on this measure (Wilks’ Lambda=.91, F(8,218)= 2.57, p = .011). The variables of education and age were controlled due to their significance. Furthermore, the univariate outcomes showed that the UK sample was significantly more impaired on role emotional (F(1,225) = 3.05, p = .022) and mental health functioning (F(1,225) = 9.39, p = .002) than the US sample.

|

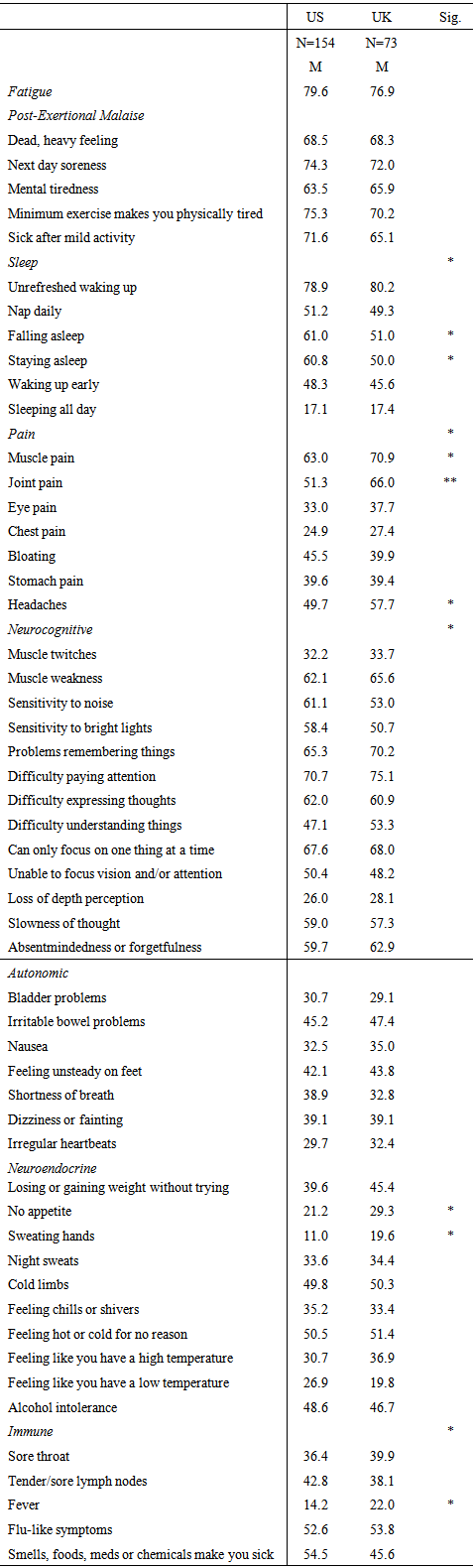

3.4. DePaul Symptom Questionnaire

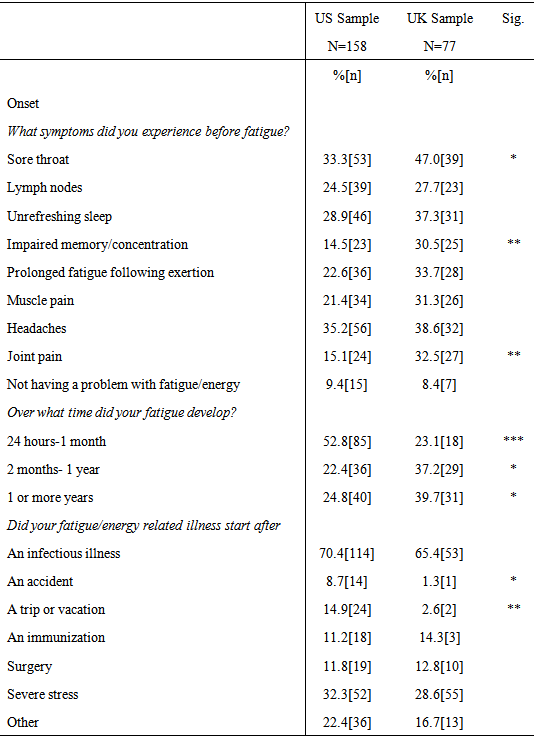

3.4.1. Onset Characteristics

- Table 3 includes data from questions of onset of individuals that completed the DSQ. Chi-square analyses revealed significant differences between the US and UK sample with regard to the number of symptoms that preceded the onset of the illness and onset duration. Participants in the UK sample were significantly more likely to report experiencing sore throats (χ2 (1, N = 83) = 4.32, p = .038), impairments in memory or concentration (χ2 (1, N = 82) = 8.71, p = .003), and joint pain (χ2 (2, N = 83) = 10.35, p = .006) before the start of their illness. With regard to illness onset, the US sample had a significantly higher percentage of participants who reported their fatigue or energy related illness developed between twenty-four hours to one month (χ2 (1, N=161) = 18.92, p < .001), whereas the UK group had significantly more participants who reported their illness developed between two months to one year (χ2 (1, N=78) = 5.83, p = .016). The UK sample also had significantly more patients who reported their illness developed over one or more years (χ2 (1, N=78) = 5.59, p = .018). The US sample had significantly more participants who reported that their illness began after an accident (p = .04, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) and after a trip or vacation (χ2 (1, N=161) = 7.97, p = .005).

|

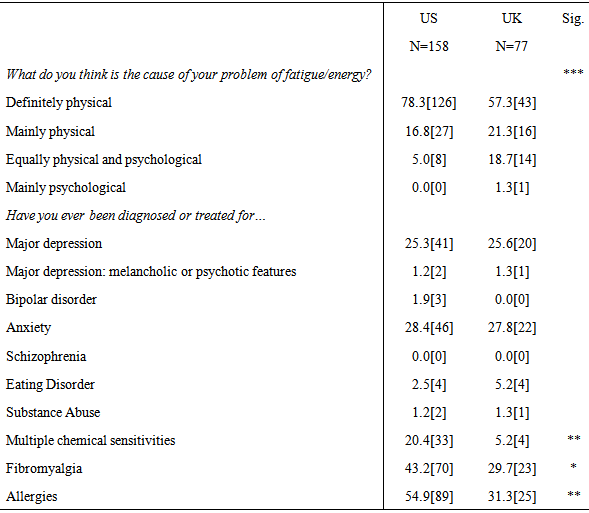

3.4.2. Perceptions of Illness Cause

- A Fisher’s exact test revealed the US sample had a significantly higher proportion of individuals who believed the cause of their fatigue related illness was ‘definitely physical’, while a higher proportion of the UK sample reported the cause of their illness was ‘equally physical and psychological’ (p <.001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) (See Table 4).

|

3.4.3. Comorbid Health Conditions

- With regard to comorbid health conditions, the US sample had significantly more participants who had been diagnosed or treated for multiple chemical sensitivities (χ2(1, N=162) = 9.19, p = .002), fibromyalgia (χ2(1, N=162) = 4.73, p = .03), and allergies (χ2(1,162) = 12.06, p = .001) than the UK sample (See Table 4).

3.4.4. Activity Level

- One-way ANOVAs using Brown-Forsythe indicated that individuals in the US sample spent significantly more time on work related activities on average before the onset of their fatigue-related illness (F(1, 132.4) = 12.28, p = .001), whereas individuals in the UK sample spent significantly more time on work related activities on average during the past four weeks (F(1, 97.1) = 10.61, p = .002) (See Table 3). Since multiple one way ANOVAs were conducted, there is an increased risk of Type 1 error, therefore, p-values with a significance of less than .01 should be considered more highly than those greater than .01. A Fisher’s exact test on the question assessing fatigue or energy during the past six months in relation to activity level and working status revealed that the UK group differed significantly from the US group (p = .044, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test); the UK sample had a higher proportion of individuals working full time, but having no energy left for anything else when compared to the US sample, which had a higher proportion of individuals on disability.

|

3.4.5. Composite Symptom Scores

- MANCOVAs were performed, controlling for the variables of education and age, on the composite symptom scores of the US and UK samples. Table 4 includes specific data on symptom domains and specific symptoms. The analysis revealed significant differences between the two samples with regard to the sleep category when controlling for education level and age (Wilks’ Lambda= .889, F(13, 190) = 1.83, p = .041), with univariate analyses showing that the US sample was more significantly impaired with regard to falling asleep and staying asleep than the UK sample. There were also significant differences between the two samples in the pain category (Wilks’ Lambda = .928, F(7,214)= 2.37, p = .024), with the UK sample group reporting significantly more impairment with regard to muscle pain, joint pain, and headaches. There were significant differences between the groups with regard to neurocognitive difficulties confirmed by a MANCOVA (Wilks’ Lambda = .887, F(13,198) = 1.95, p = .027). The UK group also reported significantly more difficulties with sweating hands and having no appetite than the US sample. There was a significant difference between the two samples in the immune category (Wilks’ Lambda = .940, F(5,215) = 2.76, p = .019). Univariate tests revealed the UK sample was experiencing significantly more impairment than the US sample with regard to experiencing a fever.

4. Conclusions

- The current study involved the utilization of one uniform case criteria [5] to determine whether key differences exist between individuals with CFS from the UK and US. Results of the study revealed several significant differences across the samples in terms of demographic characteristics, disability level, onset characteristics, activity level, and symptom severity. The UK sample was significantly more impaired with regard to role emotional and mental health functioning, multiple symptoms, experienced a more gradual onset of illness, and believed the cause of the illness to be both physical and psychological. The US sample experienced more sudden onset of illness, more frequently believed their illness to be physical, and more often were on disability. These results suggest possible differences in illness experience across the two samples.Analysis of the DSQ between the two samples on perceptions of illness cause revealed a higher proportion of the UK sample endorsed the belief that their illness was of equally physical and psychological causes, while a higher proportion of the US sample believed their illness was definitely physical. A further analysis of the UK sample revealed those who endorsed the cause of their illness as “equally physical and psychological” or “mainly psychological” more frequently endorsed having been previously diagnosed or treated with depression than the group who endorsed “definitely physical” or “mainly physical”. These results suggest those who believe their illness is partly psychological may have had previous experience with a psychological illness such as depression, which may influence their perception of the illness. Furthermore, these individuals had been previously diagnosed with a psychiatric illness (depression) by a physician. It is possible if a physician believes the cause of the illness is more psychological than physical, they may be more likely to diagnose an individual with a psychological illness, such as depression. The perception of the illness by the physicians may then also influence the beliefs of the patients, which may account for the difference in belief of illness cause between the US and the UK samples. Previous research has suggested individuals with CFS use different methods of coping, including “maintaining activity,” where individuals disregard their symptoms and continue to participate in daily activities, and “illness accommodation”, in which individuals plan their amount of activities based on impairment levels [20]. Ray et al. [20] found that individuals who were coping through “maintaining activity” were positively correlated with less impairment in symptoms, but also positively correlated with higher anxiety. Similarly, in the current study, the UK sample more often reported their activity level as “working full-time,” and had endorsed significantly worse mental health functioning impairment on the SF-36. In Ray et al.’s study, those using the coping mechanism “illness accommodation” were positively correlated with higher impairment in symptoms, active planning of activities, feelings of positive reinterpretation, and acceptance of limitations. These results are also consistent with findings from the current study, which found that the US sample worked significantly less hours than the UK sample, and the US sample was significantly less impaired in terms of role emotional or mental health functioning. However, unlike the study by Ray et. al [20], the UK sample, which endorsed a higher activity level, reported higher impairment in symptoms, while those in the US sample, who endorsed less activity, reported less impairment in symptoms. It is possible that these distinct results from the two studies may be influenced by the different beliefs of illness cause between the two samples. The similarities between the current study and the Ray et al. [20] study on coping further support the possible differences between the UK sample and the US samples regarding mental health impairment and current activity level.There were significant differences between the two samples on the SF-36, with the UK sample experiencing significantly more impairment on the subscales of mental health functioning and role emotional. Results of a recent FDA survey (Chu, personal communication, March, 2013) showed that individuals from the US were significantly more impaired in terms of physical functioning on the SF-36 than those from the UK, while the present study did not yield any significant differences in physical functioning impairment across the UK and the US samples. These results suggest there may be differences between the UK and US in relation to impairment in functioning, where the UK is more impaired in terms of mental health. This impairment in mental health may be linked to the UK sample’s higher activity level, as well as their higher symptom frequency and severity. It is possible that, because the individuals in the UK are maintaining activity, they see an increase in impairment due to symptoms, which also may affect their mental health functioning. The differences between the results of the UK samples’ impairment in physical functioning may possibly be related to recruitment methods, as the individuals who completed the FDA survey were derived from a convenience sample.The UK sample’s significantly lower mental health functioning and role emotional scores reported on the SF-36, as well as the higher endorsement of belief that the cause of their illness is equally physical and psychological, suggest that individuals selected into the UK sample may experience more psychological impairment than those in the US sample. Furthermore, the higher proportion of individuals in the UK sample reporting a gradual illness onset is consistent with previous research which has suggested that gradual onset may be associated with more psychiatric diagnoses than sudden onset [4]. The UK sample’s more frequent endorsement of symptoms prior to onset of illness (e.g. joint pain, sore throats, and cognitive impairments) may also explain their endorsement of a more gradual onset. However, it is important to note that while the UK sample showed worse impairment in mental health functioning and more individuals believe their illness is partly psychological, there were no significant differences with regard to the frequency of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses reported across the US and UK samples. These results suggest there may be differences between the two cultures in terms of perception of the illness.Of the 100 participants in the UK sample, 4 were not included in the analysis because they met exclusionary criteria, and 13 were excluded because they did not meet the Fukuda et al. [5] case definition. More specifically, 13% of the UK sample did not meet the Fukuda et al. [5] criteria, versus 5% of the US sample. This discrepancy further suggests there may be a difference in the physicians’ interpretation of certain criteria when diagnosing individuals with the illness across cultures. These differences may lead to distinct samples, and may account for further differences between the US and UK samples.One limitation of the present study involves the lack of diversity apparent in all samples. The two samples are predominantly comprised of individuals identifying as White. Community-based epidemiology research has suggested a higher number of individuals from minority populations, especially Latino female groups, make up the overall prevalence for the illness [12]. An additional limitation of the current study is the difference in recruitment methods across the US sample and the UK sample. Specifically, the US sample was collected from a variety of sources of individuals who initially self-reported a diagnosis that was confirmed by their endorsement of symptoms and illness characteristics on the DSQ, while the UK sample was collected from physicians who referred individuals to an infirmary clinic. These two convenience samples also may include individuals who are motivated to take part in research, which may be distinct from the general population. Furthermore, there is a disparity between the sizes of the two samples, where the UK sample is smaller than the US sample. Future studies should utilize similar recruitment methods across samples in order to remove possible differences occurring as a result of recruitment, and obtain more similar sample sizes.The present findings have implications for research of treatments for ME and CFS conducted in the US and UK. Previous studies conducted in the UK and the US have also revealed conflicting results with regard to effective treatments of ME and CFS. For instance, White et al. [26] in the UK compared the effectiveness of four non-pharmacologic treatments for CFS: pacing, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Graded Exercise Therapy (GET), and specialized medical care. The results revealed that CBT and GET were more effective treatments for individuals compared to pacing. In contrast, a study by Jason et al. [15] in the US compared CBT, cognitive therapy, anaerobic activity, and relaxation and found that cognitive therapy was the most effective treatment for improving overall fatigue and health. However, a re-analysis of the data showed that participants who stayed within their energy envelope, or those who expended close to the amount of energy they had available per day, had higher improvement in physical functioning and fatigue severity than individuals who did not stay within their energy envelope [9]. These contrasting results suggest there may be differences between the two studies in terms of recruitment, methodology, or cultural differences. There have been many criticisms of the PACE trial [26] including the use of selection criteria for patients that were confounded with recovery outcomes. Kindlon (2013) found that of the 640 participants in the trial, at baseline, 12% of the CBT and 9% of the GET groups had already met the criteria for recovery in terms of physical functioning before the start of the trial. This information suggests the results of the PACE trial [26] may be affected by the amount of participants who had been considered recovered at the start of the trial. Based on the findings from the present study, it is also possible that the two populations may differ on key aspects, such as perceptions and mental health impairment, which may also contribute to the different results of these non-pharmacological treatment studies. The current study compared the UK and US samples using uniform case criteria and assessment measures. The results suggest that key differences may be present across these two samples. There may be a variety of reasons why these differences exist between the US and UK samples, including the methods used to interpret case criteria and make diagnoses, the general population’s perception of the illness, and resources available for individuals with the illness cross culturally. Another possibility for differences between the two samples is the healthcare system each country utilizes. Since the UK offers universal free health care, it may be easier for an individual in the UK to be diagnosed and treated for CFS than an individual in the US, where health care is not free. As a result, more individuals in the US who may be experiencing symptoms may not seek a physician for diagnosis because of cost. Alternatively, since the health care system in the UK is free, it may be more highly regulated and as a result, individuals who are able to be assessed may experience more severe symptoms. The results of the present study have implications for future research on cross-cultural comparisons of this debilitating illness. It is recommended that future efforts to study cross-cultural differences of ME and CFS continue to use uniform selection criteria. Specifically, future research is needed to gain a better understanding of the possible relationship between mode of illness onset, functional impairment, and perceptions of illness etiology in individuals with ME and CFS across cultures. Continued research on ME and CFS across cultures may help to inform health care providers and researchers of the reasons for differences in treatment outcomes and research findings in terms of illness experience across cultures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors appreciate the financial assistance provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number AI055735) and ME Research UK.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML