-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2015; 5(2): 62-70

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150502.03

Gaze Fixation and Receptive Prosody among Very-Low-Birth-Weight Children

Motohiro Isaki1, 2, Tadahiro Kanazawa1, Toshihiko Hinobayashi1, Jiro Kamada3

1Department of human science, Osaka University, Suita, Japan

2Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan

3Department of social welfare, Kansai University of Welfare Sciences, Kasihara, Japan

Correspondence to: Motohiro Isaki, Department of human science, Osaka University, Suita, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study examined the accuracy in a receptive prosody task and gaze fixation pattern in very-low-birth-weight school-aged children. We recorded participants’ eye movements during the task using an eye-tracking methodology. The results showed that the very-low-birth-weight group fixated on eyes significantly shorter than normal-birth-weight group. More autistic traits and lower verbal ability were associated with shorter fixation time on the eyes. More autistic traits were associated with longer fixation time on the mouth. The fixation pattern may reflect a compensatory strategy for solving the receptive prosody task.

Keywords: Very-Low-Birth-Weight children, Autistic traits, Prosody, Gaze, Eye tracker

Cite this paper: Motohiro Isaki, Tadahiro Kanazawa, Toshihiko Hinobayashi, Jiro Kamada, Gaze Fixation and Receptive Prosody among Very-Low-Birth-Weight Children, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 62-70. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150502.03.

1. Introduction

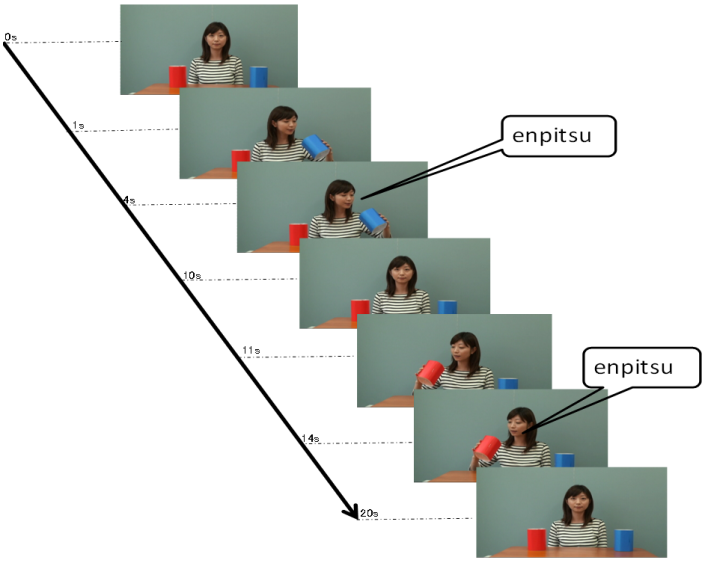

- Very-low-birth-weight (VLBW; with birth weight less than 1500 g) and/or very-preterm (VPT; gestational age under 32 weeks) infants have a high risk of long-term developmental difficulties. Many studies have revealed that VLBW and/or VPT children were associated with some social deficits (that is autism or autistic traits) [1, 2]. In recent years, studies about VLBW and/or VPT children focused on the effect of their early development In early infancy, VLBW and/or VPT infants showed atypical gaze behavior during mother-infant dyadic communication [3, 4] and they have deficits of understanding prosody (that is, the rhythm of speech) [5]. The deficits of gaze behavior during communication and understanding prosody are the signs of social deficits. But there are few studies about the gaze behavior and prosody among VLBW and/or VPT school-aged children. Weak prosody skill as a social deficitProsody refers to suprasegmental features of speech, such as voice pitch, intensity and duration [6]. Prosodic ability in VLBW school-aged children has not been investigated at all [7]. As for the relation between prosodic ability and autism, abnormal prosodic features have been observed in individuals with autism who speak [8, 9]. Moreover, the receptive prosody skills of high-functioning autism children during school days were weaker than those in typically developed children, and this skill correlated with chronological age [10]. We are concerned with whether receptive prosody skill among VLBW children remains weak or not.Atypical gaze fixation pattern as a social deficitThe abnormality of eye gaze behavior is a notable symptom of ASD. Many studies have revealed that individuals with autism exhibit deficits in gaze behavior. Children with autism also have joint attention behavior deficits [11, 12], and children with pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) differ from normal children in the timing of social gaze behavior [13]. Children with autism have problems with gaze-following behavior [14]. These studies suggest that children with autism have unique developmental ordering patterns affecting the ability to understand an other’s gaze.Eye-tracking technology is a current technique used to monitor the eye movement of individuals with autism. Klin and colleagues investigated the eye movement of adolescents with autism [15]. While watching video, these participants focused longer on the mouth of the characters in the video clips than typically developed adolescents did and spent less time focused on the eyes. Several works using the eye-tracking methodology have revealed the tendency for reduced fixation time to the eyes in individuals with autism [16-20]. Very few studies have investigated the association between the fixation time on eyes and mouth and measures of autistic traits in individuals who did not meet the criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The siblings of individuals with ASD also spent significantly less time fixated on eyes than typically developed participants [21]. This result revealed that a relationship exists between some autistic traits and abnormal fixation pattern. Freeth and colleagues revealed that a high Autism-spectrum Quotient score in undergraduate students was correlated with fixation time on the face in video clips [22]. They reported a relationship between autistic traits in normal individuals and fixation time on the face. However, they did not find an association between autistic traits and fixation time on the eyes and mouth. Moreover, the association between autistic traits in children who did not meet the criteria for ASD and fixation pattern remains unknown.This phenomenon may evidence perceptual or higher cognitive impairment concerning the ability to read others’ intentions in their eyes and the tendency to avert one’s eyes [23]. But klin and colleagues suggested that increased fixation time to the mouth represents a compensatory strategy to understand the social world [15].The aims of this study were to investigate the accuracy of receptive prosody skill using the turn-end task in Peppé and colleagues [10] and fixation patterns during the task using an eye-tracking system. We calculated the accuracy of the task and the time spent fixated on the eyes or mouth of the individual on the screen and correlated the accuracy or the fixation pattern with measures of autistic traits. Our hypotheses in this study were as follows.(1) We predicted that there were significant differences in accuracy in the receptive prosody task or the fixation pattern between VLBW children and normal birth-weight children.(2) We predicted that there was an association between accuracy in the receptive prosody task and autistic traits in VLBW children. (3) We predicted that there were associations between the fixation time on the eyes or mouth and autistic traits such that the more severe the autistic traits, the shorter the fixation time on the eyes and the longer the fixation time on the mouth.

2. Method

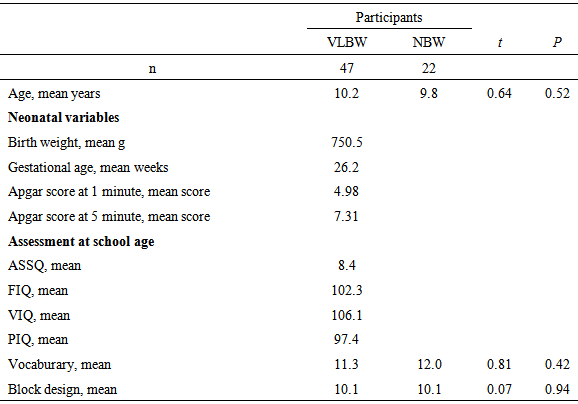

- ParticipantsThe sample consisted of 47 VLBW children and 22 normal birth-weight (NBW) children. As for VLBW group, children weighing under 1500 g at birth and with a gestational age of under 32 weeks were recruited from the hospital A. The original study cohort was enrolled in a long-term developmental follow-up. We carried out a developmental follow-up for school-aged children and 50 VLBW children participated in this study.In this experiment, we excluded the children with neurosensory impairments (deafness, blindness, or developmental disability) and intellectual disabilities. (Many researchers in previous works only included the participants with normal intelligence.) Moreover, three children were excluded due to a lack of eye movement data. (Their total fixation time was more than 1 SD below the mean fixation time of all participants.) Thus, we could use data from 47 children for fixation time. Participants and their parents provided informed written consent for entry into this study. The neonatal characteristics of these children were presented in Table 1.

|

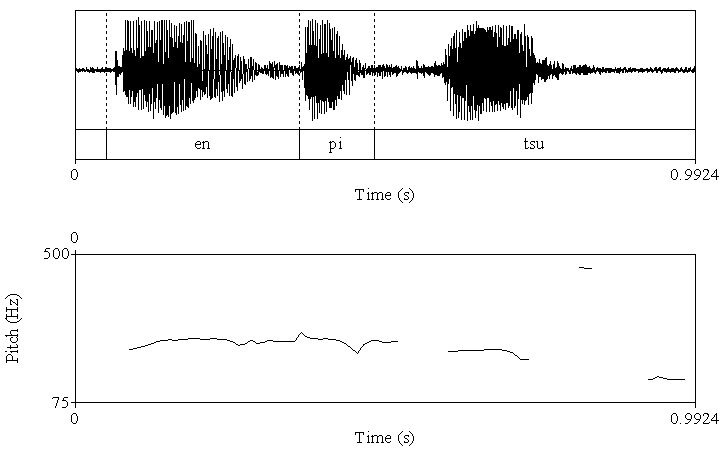

| Figure 2a. The acoustic analysis for the utterance with low pitch in the end. Upper fig shows wave form. Lower fig shows fundamental frequency |

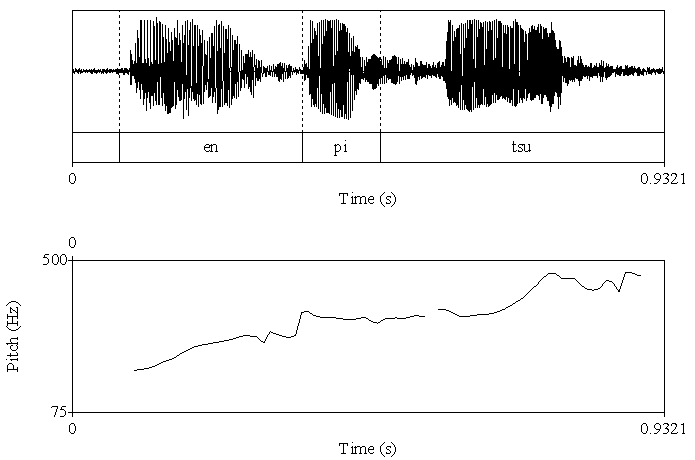

| Figure 2b. The acoustic analysis for the utterance with high pitch in the end. Upper fig shows wave form. Lower fig shows fundamental frequency |

3. Results

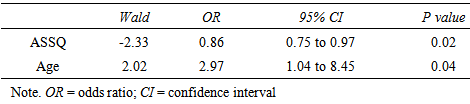

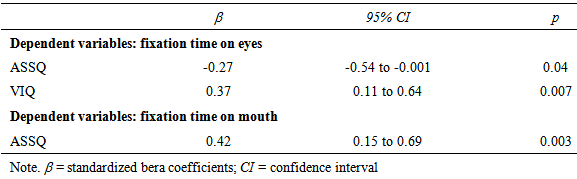

- AccuracyEach clip contained utterances with low pitch at the end and utterances with high pitch at the end. The utterance with low pitch indicated a declarative statement, whereas the utterance with high pitch indicated a question. Thus, the box containing a pencil was the box the woman indicated when ending her utterance with a low pitch. Thus, the accuracy was calculated as the number of times that the participants chose that box.First, we calculated the mean percentage scores of the accuracy in the VLBW group with those in the NBW group. All NBW children achieved 100% accuracy on this task. Compared to NBW group, some VLBW children did not achieve 100%. The mean scores in VLBW group were significantly lower than those in NBW group (t(46)=2.34, p=0.02).Next, to investigate the association between the participants’ characteristics and accuracy in VLBW group, ASSQ score and age and VIQ in association with receptive prosody accuracy were entered into a multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the relative contributions. The model containing ASSQ and age yielded the best fit to the data (AIC=29.21). ASSQ score and age accounted for the variance in the accuracy of receptive prosody (Table 2). Moreover, the VIF for the independent variables was 1.053, indicating that multicolliniarity was absent in this model. Thus, lower ASSQ and older participants were associated with high accuracy in the receptive prosody task.

|

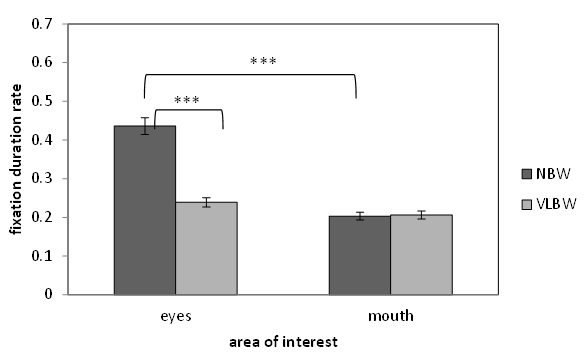

| Figure 3. Fixation duration rate spent looking at face by NBW and VLBW children. Note. ***p<0.001 |

|

|

4. Discussion

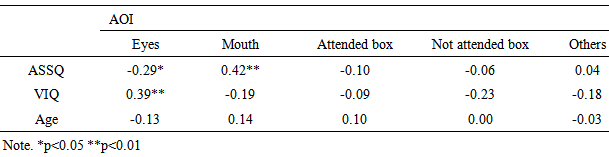

- At first, we revealed that VLBW children were different from NBW children about the accuracy and eye movement on this task. Next, we explored the relationship between comprehension of prosody and autistic traits in VLBW children and used the eye-tracking methodology to investigate how autistic traits are related to fixation patterns. Accuracy in the prosody taskFor the receptive prosody task, the logistic regression analysis revealed that the relationships between accuracy in this task and autistic traits and age were significant but that between accuracy and verbal IQ was not significant. Low accuracy in this task was linked to more autistic traits and younger participants. In this experiment, the utterance with the low pitch contour indicated a declarative statement, implying certainty in the pencil being in the box, whereas the utterance with a high pitch contour indicated a question, implying uncertainty in whether the pencil in the box. Thus, an accurate answer means that participants could identify whether the speaker indicated “certainty” or “uncertainty” using only one cue, which was derived from pitch contour. Our results show that younger participants with more autistic traits tended not to use the prosodic cue to decide whether the utterance of the speaker means certainty or uncertainty. This result was in line with Peppé and colleagues [10], in which participants had been diagnosed with high-functioning autism, representing individuals with a narrow and categorical diagnosis [31]. It was important that our participants included a wide range of autistic traits. Moreover, age was related to accuracy in the receptive prosody task. Concerning this point, our result was similar to that of Peppé and colleagues [10] but contrary to that of Chevallier and colleagues [32]. In our study and Peppé and colleagues [10], the participants were school-aged children; however, in Chevallier and colleagues [32], the participants were adolescents. This prosody task might be easier to resolve for adolescents with ASD. However, school-aged children with autistic traits might develop accuracy in this task. One possibility was the maturation of receptive prosody skill. The individuals with autistic traits delay in the acquisition of receptive prosody skill compared with typically developed individuals [10]. To understand the utterance intention with prosodic cues, children need to acquire the ‘theory of mind’ ability [33]. Children with ASD may delay understanding of the receptive prosody skill because of a disability affecting theory of mind [34]. Another possibility is the development of compensatory strategies [35]. Studies using functional MRI showed evidence of compensatory strategies. Children with ASD showed greater activity in the right inferior frontal gyrus and bilateral temporal regions, which are considered to be involved in theory of mind abilities, relative to typically developed children [36]. Interestingly, autistic children with high verbal IQ showed greater activity in these regions. Hesling and colleagues found a correlation between the left supra marginal gyrus, which is the phonological storage area, and the receptive prosody task in individuals with high-functioning autism [37]. We did not adopt the fMRI methodology, using an eye-tracking system as a physiological measure. Eye-tracking data may be helpful in discussing compensatory strategies, as will be described later.Gaze fixation patternIn the current study, we found an association between more autistic traits in school-aged VLBW children and longer mouth fixation time and shorter eyes fixation time while watching a video. Freeth and colleagues showed that typically developed individuals with more autistic traits spent less time looking at other people’s faces [22]. Our results were similar to those in Freeth et al.’s work in that the viewing pattern was related to not only ASD diagnosis but also autistic traits. However, Freeth et al.’s work did not clarify whether autistic traits influence the viewing time for the eyes or mouth. Thus, our study was the first to reveal that autistic traits in school-aged children affect fixation time on the eyes or mouth. Previous studies of adolescents or adults with ASD have shown that individuals with autism tend to spend less time to looking at others’ eyes. Our results agreed with these previous studies. Our results show that fixation pattern on eyes or mouth may be related to not only autism diagnosis but also autistic traits.This eye fixation pattern may relate to the fact that individuals with autism tend not to meet others’ gazes. Individuals with autism exhibit reduced eye contact when listening to another’s speech [38]. Dalton et al. mentioned that eye fixation patterns in individuals with autism may indicate active avoidance of eye contact [16]. The symptom of failing to make eye contact may be a precursor of theory of mind deficits [39]. Interestingly, our eye-tracking data revealed that school-aged VLBW children with higher verbal IQ exhibited increased fixation time on the eyes. This result means that the eye fixation pattern may relate not only to the autistic traits but also verbal skill. One possible explanation of this result is that verbal ability relates not to general autistic traits but to a specific autistic trait. We created three sub scales based on a factor analysis on ASSQ [40]. However, there were no significant correlations between VIQ and the three sub scales.A second possibility is that this result indicates that fixation time on eyes is related to listening or thinking strategy in individuals with autism. Children with autism exhibited increased gaze aversion with increasing cognitive demand [41]. The video clips in our experiment required the participants to answer the question by listening to the utterance. Participants with low verbal IQ might require more effort to solve our task, corresponding to increased gaze aversion and reduced fixation time on eyes. Our results showed that the accuracy of this task was not associated with VIQ. Participants with low VIQ could solve the receptive prosody task, but they might need to exert more effort. Previous researches suggested that fMRI data indicate the use of a compensatory strategy to solve the prosody task [36, 37]. Klin and colleagues [15] suggested that increased fixation time to the mouth represents a compensatory strategy to understand the social world. That is, our eye-tracking data that VIQ was associated with fixation time to mouth may indicate the use of compensatory strategy to solve the task.

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, we explored accuracy in a receptive prosody task and gaze fixation pattern in school-aged VLBW children. Our results led to two main conclusions: (1) accuracy in the prosody task was associated with autistic traits; (2) the fixation time on eyes and mouth were associated with autistic traits, and the fixation time on eyes was associated with VIQ. Thus, the receptive prosody skill and face fixation pattern in VLBW children are related to autistic traits. VLBW children with more autistic traits and lower VIQ looked spent less time looking at others’ eyes. The fixation patterns might indicate the use of a compensatory strategy to solve the receptive prosody task.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are indebted to all the staff in the hospital for permitting us to execute this study. We would like to thank the children and their families for participating in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML