-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2015; 5(2): 53-61

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150502.02

Sleeping in Separate Rooms due to Marital Conflict: Psychological Characteristics of Married Korean Women

1Department of Psychotherapy, Jeju National University, Korea

2Department of Psychology, Chonnam National University, Korea

Correspondence to: Gahyun Youn , Department of Psychology, Chonnam National University, Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Some Korean couples choose to sleep in separate rooms as a coping mechanism after marital conflict. Thematic analysis with qualitative data of 21 married Korean women explores the entire process of marital conflict, from the cause of marital conflict to the return to co-sleeping. The major findings are: (1) There is no difference between the causes of marital conflict that leads to SSR (sleeping in separate rooms) and those causes of marital conflict that do not; (2) During SSR, Korean women want to sleep with their husband to relieve their own sexual frustration; (3) after SSR there is an intention on behalf of both husband and wife to return to co-sleeping as well as social pressure for the couple to return to a seemingly healthy relationship; (4) the feelings of discomfort are reduced while the pair has sexual intercourse. The findings of this study will help family therapists or clinical psychologists to understand family dynamics as they handle divorce or marital conflict cases.

Keywords: Marital Conflict, Married Korean Women, Sexual Intimacy, Sleeping in Separate Rooms

Cite this paper: Jinhee Park , Gahyun Youn , Sleeping in Separate Rooms due to Marital Conflict: Psychological Characteristics of Married Korean Women, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 53-61. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In most cultures, sharing a bed is a custom and a marital obligation. When a couple has experienced severe marital discord, however, it leads easily to divorce instead of attempts to improve and maintain the relationship [1-3]. Until recently, Korean couples going through marital conflict, though the marital conflict is severe, would not easily divorce due to the traditional viewpoints that a married couple is thought to be of one body, one soul [4-5]. Thus, in Korea, some couples continue living in the same house, but choose to sleep in separate rooms (SSR) for a time period to avoid or resolve extant conflict; this starkly differs from marital conflict strategies in other countries that leads to separation or divorce [6-7]. In a Korean-based study of married men (n=300) and women (n=316) between the ages of 30 and 89, about 30% experienced SSR due to marital conflict at least one point in their marriage. Although the duration of SSR varied, they were typically several days [6-7].Park and Youn [7] found there were no gender differences regarding support or opposition of SSR as a means of avoiding conflict. The idea the anger may be more intense during a face to face argument or a fight is one of the supportive reasons for why men and woman could potentially choose SRR. In roughly half of the study’s cases, sleeping apart from each other not only lowered the degree of personal anger and other negative emotions, but it also offered time to think about and understand the spouse’s position. According to almost one-third of the cases, evidence suggested gender differences underpinning why spouses chose to sleep apart. Men responded that when they fought with their spouse, they could not directly communicate their feelings; they did not want to see their wives. SSR emerged as a strategy to avoid seeing each other. In contrast, women responded that they objected to having any level of intimacy if they were in the same room during fighting with their spouse and/or the aftermath of the fight. Thus, both husbands and wives supported SSR, but ostensibly for different reasons. Examples cited in the study included: the desire to avoid conflicts, desire to dampen personal anger, desire to acquire personal distance in order to think about things, the desire to get home distance so that one is more likely to sleep well, and the fear of potential physical conflict [6-7].The study also examined reasons why husbands and wives opposed SSR. Foremost, the conflict between a husband and wife was ameliorated if, immediately after a couple fought, they shared one blanket and engaged in light physical contact. Traditional Koreans consider marital strife to be similar to “cutting water with a sword.” This means: marital strife can easily be resolved because a wife’s hurt can be soothed via sexual intercourse with her husband. Thus, approximately 45% of respondents reported of having sexual intercourse during or after the process of resolving the conflict. This reflects the Korean belief that if a couple who is fighting shares one blanket they can easily resolve the conflict through close physical contact. Couples also reported that SSR was detrimental to their children’s education or healthy development. Further, couples reported that the (over) use of SSR could lead to more negative outcomes, potentially even divorce. That is, if sleeping apart due to marital conflict became a habit, even the smallest of arguments resulted in the couple’s SSR; in some cases, this pattern of behavior led to separation and divorce.Although most reasons for SSR during marital conflict are related to sexual activity, there was also gender differences discovered within the research. Women believe, if she and her spouse sleep in separate rooms after marital conflict and the man’s opportunity for sexual intercourse is taken away, his sexual frustration will amplify to the point of discomfort. The wife offers her body to the husband to improve his emotional state and to mitigate his sexual anxiety. The man, on the other hand, believes that the woman’s orgasm will calm her if the spouses have sexual intercourse during the conflict resolution. In both cases, each spouse believes that the act of sexual intercourse will allow them to resolve the conflict more easily [7].The present study researched the psychological characteristics of women with respect to sexual activity during the resolution of a marital conflict, from SSR to conflict resolution, defined as a husband’s attempt to cognitively and behaviorally empathize with his wife’s position. The study also brings to light the catalytic role of sexual intercourse during the conflict resolution. A Korean couple’s private life is so secretive that some study participants found it difficult to provide their information. Korean couples believe that any shortcomings in their relationship will cause them embarrassment and shame if discovered, especially with respect to sex and/or marital conflict. This study is of a qualitative nature because a quantitative study cannot reveal a woman’s psychological characteristics during conflict resolution with respect to sexual activity. The chosen qualitative study design is suitable to sufficiently investigate the causes of marital conflicts leading to SSR, the communication style and interaction patterns between the spouses during conflict resolution and the chances of sexual activity or conflict resolution.The purpose of this study, which used a qualitative anecdotal or analytical approach, was to explore the psychological characteristics of married woman during a marital conflict related to the process of conflict resolution, from SSR to once again sleeping together in the same room and eventually to sexual intercourse and final conflict resolution. This study consisted of three phases, starting from the causes of marital conflicts to conflict resolution. In phase 1, the study first questioned the cause of the marital conflict and the wife's psychological characteristics at the beginning of the dispute. Research questions were (1) the causes of marital conflict leading to SSR and (2) the difference between the causes of marital conflict that lead to SSR and those causes of marital conflict that do not. In phase 2, the study categorized situations where spouses began SSR and continued to measure the wives' psychological characteristics as well as began to look at the communication style and interaction patterns between the spouses during the resolution of the conflict. The study investigated (1) who initiated SSR and compared the psychological characteristics of the woman depending on who insisted upon SSR, (2) the communication style and psychological characteristics in the early stage of SSR and (3) the communication style and psychological characteristics in the later stage of SSR. In phase 3, the study investigated the psychological characteristics of the woman from when the couple begins sleeping together again to sexual intercourse at the end of the resolution phase of the conflict. The study looked at (1) the opportunity for co-sleeping during the conflict resolution and (2) how quickly the couple engaged in sexual intercourse upon returning to sleeping together and if, after intercourse, the conflict was considered resolved.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- Some people found it difficult to provide their personal information regarding sexual relationships, sexual activities and marital conflict for this study. The participants were “snowball sampled” and thus may be not representative of married Korean women. The audience at a lecture by a licensed clinical psychologist (the first author) at The Women’s Resources Development Center in Gwangju, Korea, was asked to introduce women who had experienced SSR due to marital conflict to the author of this article. One woman contacted the author telling her of a friend who had such experiences. Her friend was the first participant of the study. Participants were not paid for their time and their participation was on a purely volunteer basis. After interviewing, some of the participants were offered additional counselling free of charge if they wanted.Finally, participants of this study were 21 married women with a mean age of 42.5 years (SD=5.1, Range=34-55) and a mean marriage duration of 15.4 years (SD=5.7, Range=7-28). They had at least three rooms in their living environment and a minimum of 14 years of education. Three of the women were unemployed, 18 were employed and all the participants' husbands had jobs. The criteria for inclusion in this study were as follows: 1) female, 2) has used SSR as a coping method during conflict resolution at least twice, 3) the duration of sleeping apart was between one day and 2 months and 4) at least 5 years of marriage.

2.2. The Interview

- The interviews were conducted by the first author who is female between 2010 and 2012. All participants were informed about the purpose of this study and signed an informed consent. During the interview, if the participants wanted to stop at any time, they could with a simple request without any consequences. No one dropped out. They were also informed that all interview information would be used for the purpose of this study only and anonymity was guaranteed. A particular question was skipped if the participants comfort level was such that she was unwilling or unable to respond to this question.The semi-structured in-depth interviews, which were based on the previous study [7], lasted between 60 and 90 minutes for most of the participants. The participants were interviewed in either an interview room at a local community center (n=15) or at the participant's house (n=6), wherever the participants felt more comfortable. The interviews included questions that measured the following; cause of marital conflict, psychological characteristics of the woman during the resolution of the conflict, sleeping arrangements during the conflict, levels of communication and interaction patterns, opportunity for sleeping together, opportunity for sexual activity, and the women’s perspective on sexual activity.

2.3. Analysis

- The interviews with all 21 women were recorded and fully transcribed. The transcriptions were verbatim. Major data coding strategies used in thematic analysis were applied [8]. As the initial coding stages, familiarizing with data, generating initial codes and searching for themes among codes were done by the current authors. In this stage many codes were redundant to the research questions and thus the level of agreement reached only 73.8% by Cohen's kappa statistic. After the intermediate stages of reviewing, as well as defining and naming themes, the authors asked two professional psychologists to examine the results of both the initial steps and the intermediate steps. Herein, the data were reassembled and condensed based on logical connections between categories. The agreement percentages were over 98.0% between the coders and the examiners at this step. At the last stage of the final report, the core categories were determined according to the three phases of this study. That is, the final codes were refined and grouped in phases. Phase 1 looked at the causes of marital conflict, Phase 2 at the process of sleeping apart and Phase 3 at the resolution of the conflict.

3. Results

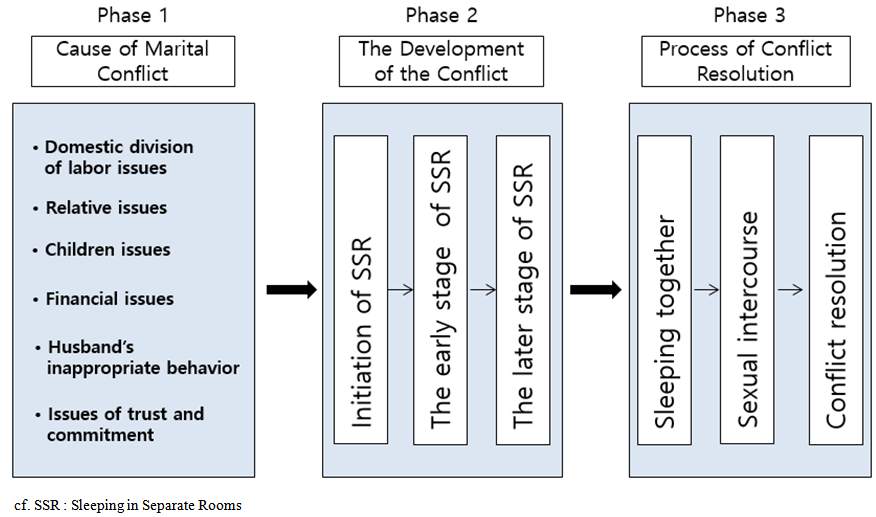

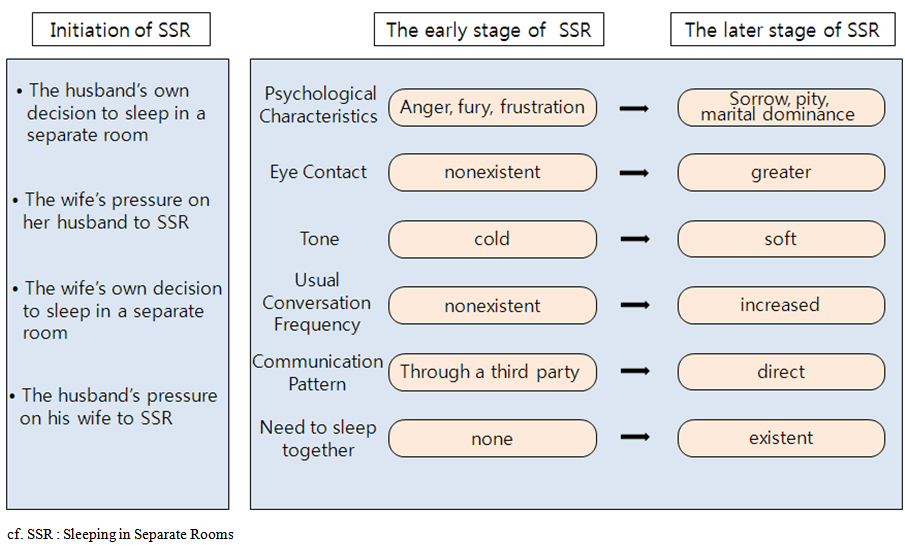

- In this study, the entire process of marital conflict resolution was covered, from the initial argument to the final stage of resolution. Figure 1 shows a synopsis of the different phases of the process, from the causes of marital conflict to steps of SSR to the final resolution. Figure 2 offers a more detailed look at Phase 2, the process of sleeping apart explaining the initial, former and latter stages.

| Figure 1. Three Phases of Marital Conflict |

| Figure 2. The Development of the Conflict |

3.1. Phase 1: Causes of Marital Conflicts

- The causes of marital conflicts listed below are based on the statements of the women’s most seriously perceived marital conflicts regarding SSR. Therefore, those statements were from the point of view of the women and make sense in the Korean culture especially. However, there may be underlying causes that they couldn’t or didn’t recognize or that they didn’t want to say to an interviewer. Also, the husbands may, of course, have seen things differently.Cause of Marital ConflictDomestic division of labor issues: Participants (n=4; 3 employed, 1 unemployed) experience a conflict due to the domestic division of labor. The husband does not help with household chores, but enjoys leisure activities instead, such as hobbies or hanging out with friends. Although the husband helps his wife, the labor is still primarily the wife's responsibility. Either way, it leads to a very heavy workload for the wife. When the husband helps out slightly, he tends to think that he helps out more than he does. From the perspective of the wife, she believes that the responsibility within the family should fall on both, the husband and the wife.Relative issues: For some participants (n=4), the conflict causes are related to a relative issue, the husband's parent’s household, more so when compared to the woman's parent’s household. When the wife airs a grievance to her husband about his parent’s household, the husband does not sympathize. For example, when a couple visits the husband’s family for a holiday or other celebration and the wife is disrespected by a member of the husband’s family, she becomes annoyed and upset and considers herself a victim when the husband does nothing to remedy the situation. There is also the example of a husband’s insistence that his wife respects his mother and father under any circumstances even if he cares little about her family. In each case, marital conflict ensues.Children issues: For other participants (n=4) a conflict occurs when problems arise surrounding the education of their children (e.g., disagreement about attending after-school programs) or in the details of a special event dedicated to their children (e.g., grandeur of a 1-year birthday party).Financial issues: The participants’ financial situation (n=3) are sometimes the root of marital conflict. For example, the husband's income is insufficient and the family cannot afford luxuries as a result. Also, the husband supports his own family but not the wife's family. Those circumstances lead to marital conflict.Husband’s inappropriate behavior: Marital conflict can also arise from the husband's inappropriate behavior, such as heavy drinking, gambling and verbal abuse (n=3). For example, in some of the reported cases, husbands would come home after a night of drinking and cause family discomfort due to noise levels, verbal abuse and other inappropriate behavior. Another example is gambling. A gambling husband is neglecting the family in his wife’s eyes. In case of verbal abuse, the wife’s pride is hurt and she herself feels being neglected by her husband. Each instance can lead to conflicts and ultimately to SSR.Issues of trust and commitment: In other cases (n=3), the personality of either spouse can also lead to marital conflict. For example, the wife doubts the husband's commitment to the marriage (she suspects an affair after seeing a text on her husband’s phone from another woman or after repeated late nights) and complains he is not showing enough sympathy towards her.Unresolved ConflictsThe issues and problems related to the conflict primarily weighed heavy on the wife's psychological state during the disputes due to a lack of communication and common ground. When the two faced each other in the same room, emotions rose out of control and the wife felt anger and animosity towards her husband. For instance, a respondent said:Because we can’t find a common ground I was angry and annoyed. I wanted to end the relationship. I was so disappointed with him I hated looking at his face and couldn't stand to be in the same room as him. (Age 45).

3.2. Phase 2: The Development of the Conflict

- In this stage, the marital conflict was not amicably resolved by one of the spouses. This led to the initial stage of SSR, the request or demand for SSR. The conflict then further advanced to the former and latter stages of SSR, explained in the table below.Initiation of SSRFour conditions of SSRIn this study, four different conditions of SSR were identified. They were as follows: 1) the husband's own decision to sleep in a different room, 2) the wife's pressure on her husband to sleep in a separate room, 3) the wife's own decision to sleep in a different room and 4) the husband’s pressure on his wife to sleep in a separate room.Unresolved ConflictThe wife's relief due to the reduction of contact with her husband was a common result of SSR in all four conditions above. In each condition, even at the request or pressure from the wife, some women believed that couples should sleep together even if they fought. When the husband moved to another room to sleep, 5 out of the 21 women felt betrayed and rejected. Eight women were appalled that her husband would sleep in another room while others were thankful that the husband was gone. Four women, who left the bedroom to sleep in another room, whether it was their decision or from the husband’s pressure to do so, secretly wished the husband would dissuade them from leaving. The other four women wanted their husband to spend a night feeling lonely while others wanted to be in control of their husband's opportunity for sex. They chose SSR deliberately as revenge. The respondents explained:I left the bedroom to sleep in another room. It was my decision but I secretly wanted my husband to try to stop me from going. (Age 51).When he avoided the conflict I took it as him rejecting me. This lowered my respect. I believe that even if a couple is fighting they should sleep together...but he avoided me and so I felt he rejected me. (Age 45).Because my husband avoided the situation I was able to calm down and our fight was done before it went too far. When it gets to that point, if one of us avoids the situation it gives us time to think deeply about our situation and as times goes on we calm down. (Age 46).I left the bedroom so my husband could spend the night feeling lonely. I also wanted to be in control of my husband's opportunity for sex. It was a sort of revenge. (Age 38).The Early Stage of SSRCommunication StyleThe communication style during the former SSR is divided into two categories; verbal and non-verbal. During verbal communication, eye contact was nonexistent and conversation between spouses was short, to the point and in a cold tone. During SSR, the couple communicated mainly through their children or through the use of very short expressions, speaking quickly and briefly and without eye contact. They sometimes treated the other as invisible by not speaking and by communicating through action. For instance, the wife would not announce dinner was ready, but would simply set the table and then leave the dining room.Unresolved ConflictDuring the former SSR, the emotion of most women in this study is described as being furious. She does not want to share a bed with her husband because he has yet to approach her to initiate a resolution of the conflict. In this phase she feels frustrated with her husband because they cannot or will not engage in a healthy conversation needed to resolve the conflict. She therefore avoids him. The wives argued:Even though we talked we had little or no eye contact and our conversations were very short. During this time I treated my husband as an invisible person. (Age 51).I was getting more and more angry. If he would have come into the bedroom and given any indication that he was sorry I would have accepted it. But he didn't, and this made me even angrier. (Age 35).The Later Stage of SSRCommunication patternAccording to the majority of participants the husband became more approachable as the verbal and non-verbal communication increased during the latter stage of SSR. The wife felt slightly sorry for the husband as well, but as time went on that unpleasant feeling subsided. For example, the frequency of eye-contact during the latter stage of SSR is greater than that during the former stage. In addition, the frequency of usual conversations increases during the latter stage and the tone used by each spouse becomes softer.Unresolved ConflictDuring the latter stage of SSR, the communication level returns to approximately normal and the frequency with which the wife refuses to sleep with the husband slightly decreases. Most participants reported their emotional state changes during this stage. For instance, she feels sorry she treated her husband the way she did and begins to feel pity toward him and even guilt for her actions. However, the wives would often not initiate conflict resolution through actively approaching their husband because of fear to lose the role of marital dominance. Instead, they would often wait for their husband's active approach. For example, two women mentioned:When couples live together they have empathy for each other. When I see my husband sleeping in the living room or in the kids' bed alone, I feel sorry for him. (Age 45)If I didn't make a mistake why should I start the conversation to begin reconciliation? He made the mistake. He should come to me. He should apologize to me first. Of course, I can take the first step, but I have to maintain my self-respect. I cannot approach my husband because of fear to lose my marital dominance. (Age 35)

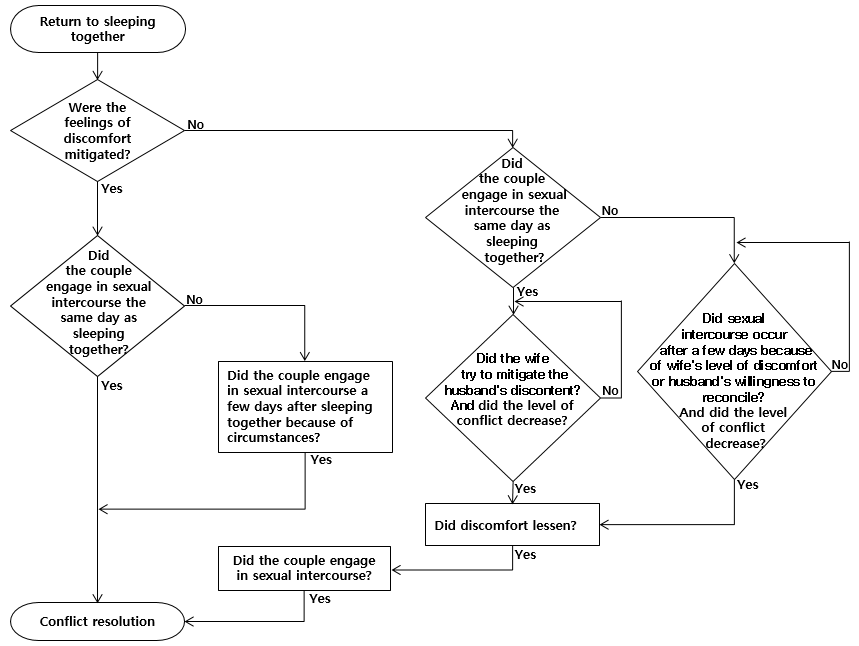

3.3. Phase 3: Process of Conflict Resolution

- In this phase, SSR ends and sleeping together in the same room returns. The speed and degree to which the conflict resolution occurred (e.g., the amount of concern shown by the husband) was shown to depend on how much the wife's discomfort level was resolved. It also depended on when sexual relations occurred upon returning to sleeping together. Also the wife’s perspective before, during and after sexual intercourse was a factor. Thus, this stage is divided into four categories and the process of conflict resolution is summarized as shown in Figure 3.

| Figure 3. Process of Conflict Resolution |

4. Discussion

- This study’s population was composed solely of Korean married women. It looked to understand and analyze the reconciliation process from conflict occurrence to conflict resolution in the lives of married Koreans. In particular, this study investigated the wife’s psychological characteristics as they evolved through the process of conflict resolution. In Korea, when a married couple experiences conflict, many choose SSR to temporarily avoid conflict until it can be resolved later. There are few studies researching this phenomenon. Therefore, this study explored the woman's psychological changes during the phases of a couple’s conflict resolution. It explores the beginning, to the cause of the conflict, the development of the conflict, the levels of interaction between spouses during each phase, the results of SSR and the sexual activity after conflict resolution. Based on the research question of whether SSR would be a means of avoiding or resolving conflict, the following discussion describes the results of the study.First, when a women experiences conflict during the early stage of a dispute, constructive communication breaks down and the level of conflict increases. Couples therefore choose SSR as a means of avoiding conflict.Second, four different scenarios were identified and explored to describe the initiation of SSR: 1) the husband independently chose to sleep in a separate room, 2) the wife forced the husband to sleep in a separate room, 3) the wife independently chose to sleep in a separate room and 4) the wife was forced by her husband to sleep in a separate room. The original belief was that the initial cause of the conflict would predict which scenario would ensue: That was not the case. According to the interviewed women, irrespective of who was the root cause of the conflict, the husband and/or wife chose to avoid conflict by initiating SSR.Third, the women’s psychological state varied at the onset of SSR; there was a wide variety of emotions ranging from relief that the conflict would not continue, to women who viewed SSR as a means to assert power over sexual access, to those who experienced hurt feelings that a husband may be leveraging SSR to avoid sexual activity. Indeed, some women immediately felt better, while others felt rejected by their husbands and were disgusted with their husband's actions. Some women were thankful to avoid further communication and physical contact, while others entertained themselves with thoughts of revenge. Some women did not want their husband to leave, even though she asked him to sleep in a separate room. One wife left the room because she did not want to see her husband: However, in her mind, she wanted him to stop her from leaving. In other cases, wives thought they had to share a bed, even if they were in conflict. The wife felt betrayed when her husband left to sleep in another room. She also felt rejected and believed her husband was leaving the room to avoid sexual activity.Fourth, according to the women, the couple didn’t share their opinions or emotions directly with each other during SSR; they communicated indirectly through their children or through abbreviated short expressions without eye contact. Otherwise, they treated their spouse as invisible.Fifth, according to women's responses, when the couple perceived the conflict had decreased to a certain point, the wife and or her husband had the intention to stop SSR. The decision to stop SSR, therefore, was usually caused by one of three catalysts: the wife's intention, the husband's intention, or the pressure of a third party (such as children) to repair the uncomfortable relationship. Most women stated that her husband believed the first level of conflict will be resolved through sexual intercourse. Generally, a couple whose sexual relationship was satisfying and appropriate had a shorter length of SSR compared to couples whose sexual relationship was originally unhealthy. Some participants believed the reason underpinning their longer SSR length was the original low frequency of sexual intercourse with the husband’s sexually inactivity compared to other couples.Sixth, married women reported they could understand that married couples can settle conflict through sexual intimacy, although their view of sex in the marriage diverged from that of the husband. A woman who experienced discomfort, even after the conflict was resolved, reported wanting to deny or avoid their husband's sexual approach. Many women reported that their husbands mistakenly believe sexual intercourse would solve all problems. This reflects the belief of Korean men that sexual intercourse can resolve marital conflict [7].Seventh, the study defined SSR itself with respect to couples who used it as a method of reaction during conflict. SSR began because (1) the wife wanted to make evident her anger to her husband, (2) the couple needed time and space to calm down before facing their spouse, and (3) to intentionally cause her husband's sexual frustration. Even though SSR was not initiated in all situations, some wives reported denying their husband’s request or demand for intercourse in order to intensify the husband’s pain and discomfort. Even when sharing a bed after SSR, the woman rejected her husband’s advances if she was still emotionally discontent. After a period of time, including increased communication and the performance of housing chores or helping out with the children, most wives reported they were willing to accept their husbands' sexual advances if the wife believed her husband regretted his behavior. Some wives reported the conflict was truly resolved only after having sexual intercourse. Others said they leveraged sexual intercourse to find common ground with their husbands: That is, they strategically used intercourse as a way to calibrate the tension of SSR to an appropriate level where peace could be maintained in the house and a non-hostile relationship with the husband ensued.Women in the study stated many Korean husbands believe that satisfying a wife sexually can end conflicts. Korean men also tend to think that they should have sex regardless of their partners’ mood or state of health. Indeed, their sexuality is characterized as hyperactive, which may have resulted from the fear of losing one’s virility [5, 9]. They may want to ameliorate their relationship problems: However, at the same time, they are also too embarrassed to attend sexual therapy in order to improve their sexual satisfaction and/or to treat their sexual dysfunction. There is more demand for medical interventions related to sex therapy as sexual intercourse is important for Korean couples, especially for men, to resolve their conflicts [5].Eighth, initiation of SSR to conflict resolution, or duration of SSR, was less than a week for a majority of the sample (n=15) but over 1 week to 6 weeks for the remaining six.Finally, this study has numerous limitations and suggestions for further studies. First, all study participants were married women. As a result, there are considerable doubts that a married woman would be completely honest sharing their total experience with the researcher due to of privacy concerns. The use of snowball sampling to find study participants is also a notable limitation. It was hard to select participants due to the privacy issues of Korean couples. This study also raises a number of questions for future research. This study focuses on the progress of the couple’s conflict trajectory, SSR behavior, and sleeping together from the woman’s point of view. More research is needed on the psychological state of men during the process of conflict resolution. In this context, studying a man's psychology, or the perceived gap between a woman’s and man’s psychology during the process of conflict resolution, and in particular, SSR, would be a valuable asset in the design of marriage counselling and treatment.Third, this study is also limited by the lack of quantitative measures of sexual satisfaction and marital state satisfaction (through, for example, GRISS [10]) or GRIMS [11]). These measures would have been more accurate than the anecdotal measure taken.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors extend their thanks to the participants and to the following individuals who assisted with data analysis: Drs. S. Kim & D. Yang of Psychology Department, Chonnam National University.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML