-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2015; 5(1): 26-34

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150501.04

Academic Stress, Parental Pressure, Anxiety and Mental Health among Indian High School Students

Sibnath Deb1, Esben Strodl2, Jiandong Sun3

1Department of Applied Psychology, Pondicherry University, Puducherry, India

2School of Psychology and Counselling, Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove, Australia

3School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove, Australia

Correspondence to: Esben Strodl, School of Psychology and Counselling, Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work investigates the academic stress and mental health of Indian high school students and the associations between various psychosocial factors and academic stress. A total of190 students from grades 11 and 12 (mean age: 16.72 years) from three government-aided and three private schools in Kolkata India were surveyed in the study. Data collection involved using a specially designed structured questionnaire as well as the General Health Questionnaire. Nearly two-thirds (63.5%) of the students reported stress due to academic pressure – with no significant differences across gender, age, grade, and several other personal factors. About two-thirds (66%) of the students reported feeling pressure from their parents for better academic performance. The degree of parental pressure experienced differed significantly across the educational levels of the parents, mother’s occupation, number of private tutors, and academic performance. In particular, children of fathers possessing a lower education level (non-graduates) were found to be more likely to perceive pressure for better academic performance. About one-thirds (32.6%) of the students were symptomatic of psychiatric caseness and 81.6% reported examination-related anxiety. Academic stress was positively correlated with parental pressure and psychiatric problems, while examination-related anxiety also was positively related to psychiatric problems. Academic stress is a serious issue which affects nearly two thirds of senior high school students in Kolkata. Potential methods for combating the challenges of academic pressure are suggested.

Keywords: India, Secondary School, Academic Stress

Cite this paper: Sibnath Deb, Esben Strodl, Jiandong Sun, Academic Stress, Parental Pressure, Anxiety and Mental Health among Indian High School Students, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 26-34. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150501.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Academic stress involves mental distress regarding anticipated academic challenges or failure or even an awareness of the possibility of academic failure [1]. During the school years, academic stressors may show in any aspect of the child’s environment: home, school, neighbourhood, or friendship [2, 3]. Kouzma and Kennedy reported that school-related situations – such as tests, grades, studying, self-imposed need to succeed, as well as that induced by others – are the main sources of stress for high school students [4]. The impact of academic stress is also far-reaching: high levels of academic stress have led to poor outcomes in the areas of exercise, nutrition, substance use, and self-care [5]. Furthermore academic stress is a risk factor for psychopathology. For example, fourth, fifth and sixth-grade girls who have higher levels of academic stress are more likely to experience feelings of depression [6].

1.1. The Indian Education System

- The Indian school education system is textbook-oriented that focuses on rote memorisation of lessons and demands long hours of systematic study every day. The elaborate study routines that are expected by high school students span from the morning till late evening hours, leaving little time for socialisation and recreation. In India, the school education system is governed by two major categories of educational boards recognised by the government of India. The first category includes the All-India Boards, like the CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education), the CICSE (Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations) and the National Open School. The second category includes the State Level Boards that are authorised to carry on their activities within the states where they are registered. The education system in India is highly competitive because of a lack of an adequate number of good institutions to accommodate the ever-expanding population of children. Hence children face competition at the entry level of pre-primary education, and thereafter at the end of every year, in the form of examinations that determine their promotion to the next grade. In classrooms teachers attempt to cover all aspects of a vast syllabus, often disregarding the comprehension level of students [7]. Tenth grade terminates with first board examination – in which the competition with other students expands from the school-level to the state and even the national level. Performance on the 10th grade board examination is important for a number of reasons. It determines, to a very large extent, whether a student will get to specialize in his/her preferred stream of education, and whether or not they will be admitted into the institution of his/her choice. Since the job prospects for students from the science stream is somewhat better than that for students of humanities and commerce, the popular choice for most of the students and their guardians is the science stream in Grade 11. The choice made regarding stream of study is often irrevocable. Unlike the situation in many Western industrialised countries, in India, it is difficult for a student to switch stream of education after leaving school. This is particularly the case for students specialising in commerce and humanities. These structural factors exacerbate the academic stress experienced by senior high school students.The 12th grade, and high school life, ends with the second board examination. The performance in the 12th grade final examination is crucial for getting admission into one’s preferred choice of college or university. The poor ratio of number of available institutions to the aspirants for college education ensures that the students face tremendous competition in getting admission to tertiary education. In addition, the majority of senior high school students who specialise in science undergo further stress as they tend to also sit for entrance examinations for admission in engineering, medical and other specialized professional courses. The pressure of preparation for examinations creates a high degree of anxiety in many students, especially in those who are unable to perform at a level that matches the potential they have shown in less stressful situations [7].

1.2. School Disciplinary Measures

- Although disciplinary measures in schools vary from institution to institution in India, corporal punishment is practiced in most of the schools in India. Corporal punishment is often used for violation of school rules, for not being able to answer questions in the class, not completing home-work, and for coming to school late. In the recent past there has been lot of discussion and debate about positive and negative aspects of corporal punishment. To date there is no specific law for prevention of corporal punishment in schools in India.

1.3. Anxiety and Stress in School Children

- Anxiety as a disorder is seen in about 8% of children and adolescents worldwide [8, 9]. There is a still larger percentage of children and adolescents in whom anxiety goes undiagnosed owing to the internalized nature of the symptoms [10]. Anxiety has substantial negative effects on children’s social, emotional and academic success [11]. Depression is becoming the most common mental health problem suffering college students these days [12] – caused by poor social problem-solving, cognitive distortions and family conflict [13], as well as with alienation from parents and peers, helpless attribution style, gender, and perceived criticism from teachers [14]. Mental health problems among children and adolescents are frequent in India as well [15, 16].Psychiatrists have expressed concern at the emergence of education as a serious source of stress for school-going children - causing high incidence of deaths by suicide [17]. Many adolescents in India are referred to hospital psychiatric units for school-related distress – exhibiting symptoms of depression, high anxiety, frequent school refusal, phobia, physical complaints, irritability, weeping spells, and decreased interest in school work [18, 19]. Fear of school failure is reinforced by both the teachers and the parents, causing children to lose interest in studies [1, 20]. This is similar to the scenario in the East Asian countries where psychiatrists use the terms ‘high school senior symptoms’ or ‘entrance examination symptoms’ to indicate mental health problems among students [21]. The self-worth of students in the Indian society is mostly determined by good academic performance, and not by vocational and/or other individual qualities [22]. Indian parents report removing their TV cable connections and vastly cutting down on their own social lives in order to monitor their children’s homework [23]. Because of academic stress and failure in examination, every day 6.23 Indian students commit suicide [24] – raising questions regarding the effects of the school system on the wellbeing of young people. Ganesh and Magdalin found that Indian children from non-disrupted families have higher academic stress than children from disrupted families [25]. It is likely that the children from disrupted families get less attention and guidance from their parents regarding academic matters than do their counterparts in non-disrupted families. This, paradoxically, reduces their academic stress – thus highlighting the negative impact of the parental vigilance and persuasion on the academic lives of their children. Given the said background, our purpose was to find out degree of academic stress of 11th and 12th grade Indian students experiences, as well its association with various psycho-social factors and its effect on mental health.

1.4. Research Questions

- 1. Do adolescent boys and girls differ significantly with respect to academic stress and examination-related anxiety?2. Is educational level of the parents positively associated with parentals expectations and pressure?3. Does the nature of academic stress vary with socio-economic status?4. Do adolescents of different age groups suffer from similar stress?5. Is there any relationship between academic stress, number of private tutors and examination-related anxiety?6. Is there any relationship between communication skills in English and examination-related anxiety?7. Are adolescents involved in extra-curricular activities less prone to academic stress?8. Is there any impact of academic stress on the mental health of adolescents?

2. Method

2.1. Sample

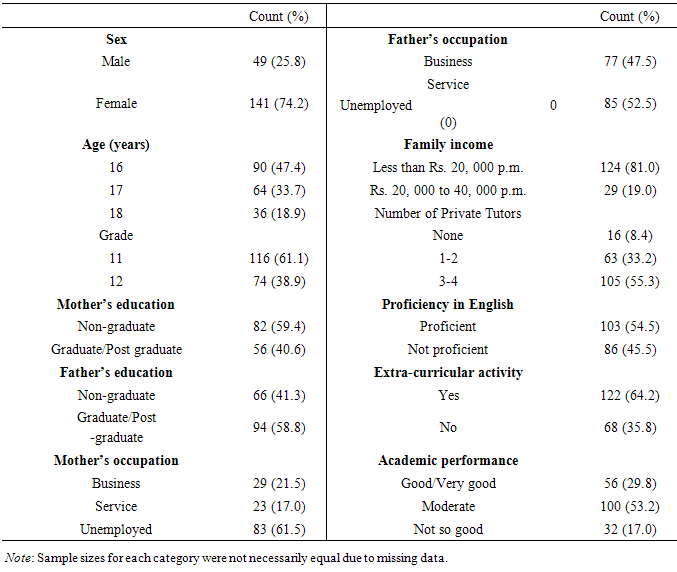

- The study was conducted on a group of 190 11th and 12th grade adolescent students from six schools – three, government-aided, and three, private – in Kolkata, one of the largest metropolitan cities in India, following the multi-stage sampling technique. Ten schools were officially approached. Four schools declined to give permission on account of examination and syllabus load. The sample included 49 boys (25.8%) and 141 girls (74.2%) aged between 16 and 18 years (mean age: 16.72 years and SD=.77). Several students could not provide information about their parents’ educational background and income. About 41% of the students had fathers who were non-graduates while for the majority of them the fathers were graduates and post graduates (58.8%). Fifty nine percent and 41% of the mothers were non-graduates and graduates/post graduates respectively. Of the fathers, 52.5% were in government services while 47.5% of them were engaged in business. Fifty two participants had working mothers – self-employed or employed in the government or private sector.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) – Goldberg and Hiller (1979)

- The GHQ is a 28 item self-administered screening test aimed at detecting short-term changes in mental health among respondents [26]. It consists of 4 subscales: (i) somatic symptoms; (ii) anxiety and insomnia, (iii) social dysfunction and (iv) severe depression. Each sub-scale consists of seven items and each item has 4 response alternatives. Scoring was done by Likert method (0-0-1-1). The total score for the questionnaire ranges from 0 to 28 and the score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 7. Threshold for case identification was taken as 4/5, i.e., scores of 4 and below signify a non-psychiatric case and scores of 5 and above signify psychiatric caseness.

2.2.2. Structured Questionnaire

- This questionnaire was developed by Dr. Sibnath Deb and has five sections. Section I: Demographic and Socio-economic Information, comprised of six items on issues like age, gender, education, parents’ education and occupation, and family income.Section II: Perception about Stress of Adolescents, comprised of eight items on feeling and level of academic stress, source of academic pressure, number and necessity of private tutors and its effects. An example of academic stress related question is as follows: ‘Do you feel stressed because of academic pressure?’ Participants are asked to respond in terms of either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Section III: Anxiety related to Examination, comprised of three items on nature and level of examination-related anxiety and perception about coping strategies. An example is provided: ‘Do you have any anxiety related to examination?’ Participants are asked to respond in terms of either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Section IV: Communication skills and Future Aspiration, comprised of three items on proficiency in English and future aspiration.Section V: Involvement in Extra-curricular Activities and Academic Performance, comprised of four items on nature of involvement in extracurricular activities, reasons for not participating in extra-curricular activities and details of the latest academic performance.For some items, the mode of response was dichotomous (yes/no), while others were multiple choice items. The questionnaire was reviewed by two experts who gave feedback on the utility of the questions, the face validity, and language of the questions. The measure has been used in other previously published research (43).

2.3. Procedure

- Written permission was obtained from all the schools after explaining the objectives of the study to the school authorities. At the time of data collection, students were briefed about the objective of the study and its justification in simple terms and were assured about confidentiality of the information. Only those students who had given informed consent for participation were covered in the study.

2.4. Data Analysis

- In addition to the descriptive analysis of data, Pearson’s chi-square test and/or Fisher’s Exact Test was applied to ascertain the associations between the mental health measures and the demographic and academic factors. Several logistic regressions were conducted to further examine the relationships between psychiatric caseness and academic stress and/or examination-related anxiety. All analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows 17.0. Statistical tests used were two-tailed with a significance level of α=0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

- Table 1 display the frequency and percentages for all demographic variables considered in this study.

|

3.2. Academic Stress and Risk Factors

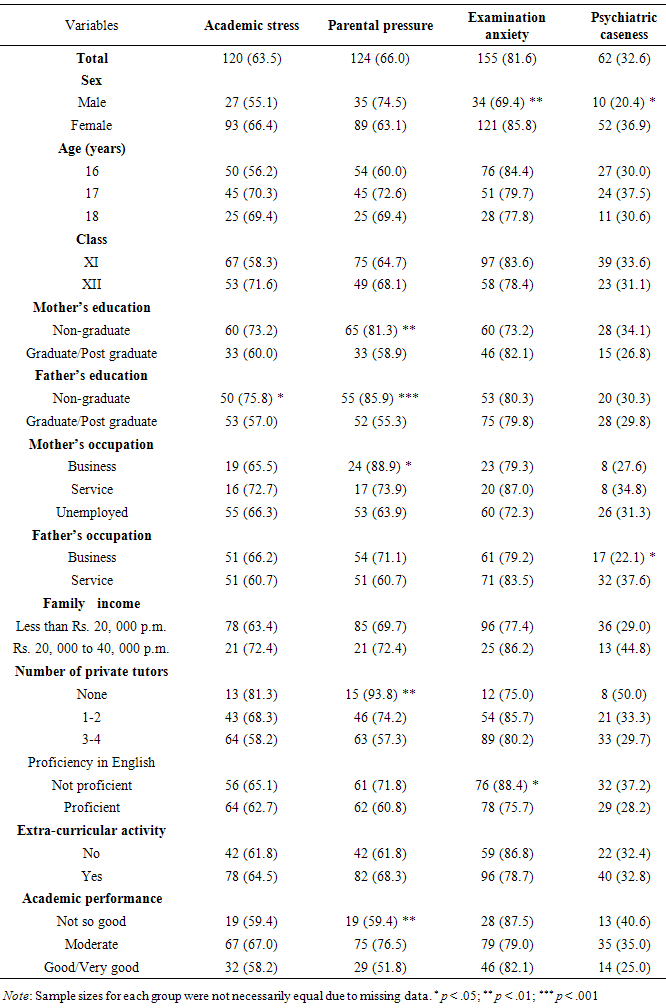

- Most of the students (63.5%) reportedly felt stressed because of academic pressure (Table 2). As shown in Table 3, education level of the father was significantly associated with academic pressure (χ2(1, N=159)=5.96, p=.015): participants whose fathers were non-graduates were found to be more likely to report academic pressure. There were no significant differences in academic stress across gender, age, class, and other factors.

|

3.3. Parental Pressure and Risk Factors

- About two-thirds (66.0%) of the students reported that their parents pressurize them for better academic performance (Table 2). Students whose parents were non-graduates (χ2(1, N=158)=16.33, p<0.001 for father education level; χ2(1, N=136)=8.15, p=.004 for mother education level); whose mothers were self-employed (χ2(2, N=133)=6.30, p=.043); who had none or at the most 1 or 2 private tutors (χ2(2, N=188)=11.07, p=.004); and who had an average level of academic performance (χ2(2, N=186)=10.53, p=.005) were more likely to experience parental pressure than their counterparts.

3.4. Examination-Related Anxiety and Risk Factors

- More than four-fifths (81.6%) of the students had some anxiety related to examination (Table 2). Female students (χ2(1, N=190)=6.53, p=.011) and those who were not proficient in communicative English (χ2(1, N=189)=4.97, p=.026) were more prone to examination-related anxiety than male students and those who were proficient in English respectively.

3.5. Mental Health and Risk Factors

- About one-third (32.6%) of the students obtained a high score (i.e., five and above) in GHQ which is above the threshold for psychiatric caseness (Table 2). Gender is found to be associated with examination-related anxiety and psychiatric caseness (p<.05). At the same time, gender (χ2(1, N=190)=4.49, p=.034) and father’s occupation (χ2(2, N=162)=4.64, p=.031) were significantly associated with increased GHQ score – with female students and students whose fathers were employed in service reporting more health problems than male students and students whose fathers were engaged in business respectively (Table 2).

3.6. Relationships between Academic Stress, Parental Pressure, Examination-related Anxiety and Mental Health

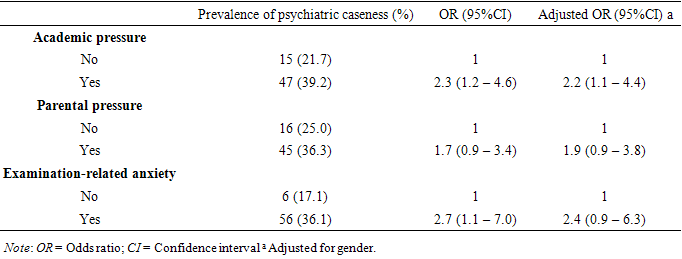

- Academic stress was positively correlated with parental pressure (χ2(1, N=187)=11.89, p=.001) but not examination anxiety (χ 2(1, N=189)=1.99, p=.158). There was no significant relationship between parental pressure and examination-related anxiety.Several logistic regressions were conducted to examine the relationships between academic stress, parental pressure, examination-related anxiety and psychiatric caseness (Table 3). Results showed that academic stress (OR=2.3, 95% CI: 1.2 – 4.6) and examination anxiety (OR=2.7, 95% CI: 1.1 – 7.0) were significantly associated with psychiatric caseness. When the impact of gender was controlled, the relationship between academic stress and mental health remained significant (Adjusted OR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1. 1 – 4.4). Parental pressure also had a positive but not statistically significant association with psychiatric caseness (Table 3).

|

4. Discussion

- The mental health of students, especially in terms of academic stress and its impact has become a serious issue among researchers and policymakers because of increasing incidence of suicides among students across the globe. The present study revealed that 63.5% of the higher secondary students in Kolkata experience academic stress. Parental pressure for better academic performance was found to be mostly responsible for academic stress, as reported by 66.0% of the students. The majority of the parents criticized their children by comparing the latter’s performance with that of the best performer in the class. As a result, instead of friendship, there develops a sense of rivalry among classmates. Some parents even tend to demean the achievement of the top scorer of the class by stating that he/she might have been favoured by the teacher [27]. There are instances of mental health problems in secondary school students (10th grade final examination) and senior high school student (12th grade final examination). Pushed by the parents to ‘be the best’ in art or music lessons and under pressure to score well in school, some students cannot cope with the demands anymore and emotionally collapse when the stress is high. Constantly pushed to perform better in both academic and extra-curricular activities, some children develop deep rooted nervous disorders in early childhood [28]. Parents put pressure on their children to succeed because of their concern for the welfare of their children and their awareness of the competition for getting admission in reputed institutions. The overall unemployment situation in India has also provoked parents to put pressure on their children for better performance. Some of the parents wish to fulfil their unfulfilled dreams through their children. All these have made a normal pursuit for adolescents [22] – leaving them to deal with the demands of the school as well as that of their tutors. More than half of the parents appoint 3 to 4 private tutors or even more for their wards. On days when there are no academic tuitions, there are art or music lessons. The students hardly get time to watch TV, to play or to interact with neighbours freely or even to get adequate sleep. Naturally such students end up being nervous wrecks when the examination pressure mounts. The data revealed that parents with low level of education i.e., non- graduates, pressure their children more than the parents with graduation and post-graduation background do. In addition, the child’s mother’s occupation, number of private tutors and the academic performance of the students are some of the other factors associated with academic stress. People from lower and middle class social strata want their children to do well in studies since this is often the only means to an honourable vocation for them. In a review of studies from low and middle income countries, Patel and Kleinman confirmed the association between indicators of poverty and the risk of common mental disorders [29]. Academic anxiety is found to be the least in case of adolescents from high socio-economic classes – which may be partly attributed to their secured future at least in material aspects. The prevalence of anxiety disorders tends to decrease with higher socio-economic status [30]. Another study has also reported that social disadvantage is associated with increased stress among students [31]. In the present study, examination-related anxiety has been reported by 81.6% of the students, especially the female students who are coming from Bengali medium schools and are not proficient in English. The students from the lower socio-economic strata get admitted in government-sponsored schools and study primarily in the local language – since in government schools in West Bengal, English education is introduced in year 8. Compelled to learn a foreign language at a late age and then to study all other participants in that ill-mastered language, the students in these schools face communication and comprehension problems, which affect their academic performance as well as their self-confidence. This leads to anxiety – causing school avoidance, decreased problem-solving abilities, and lower academic achievement [32, 33]. Gender was also found to be significantly associated with examination-related anxiety and psychiatric caseness. That is, female students experience more examination-related anxiety and psychiatric caseness than their male counterparts. This confirms previous findings that adolescent girls report a greater number of worries, more separation anxiety, and higher levels of generalised anxiety than do boys of the same age [34-37]. Deb, Chatterjee and Walsh also found higher anxiety among female students in Bengali Medium schools in India [38]. It is believed that extra-curricular activities could be one of the mediating factors for academic stress. More than three-fifths of the students reported to be involved in extra-curricular activities like games and sports, cultural programmes, National Cadet Corps (NCC) and National Social Service (NSS) and so on. No significant difference is found between the academic stress of students who are involved in extra-curricular activities and who are not. This could be because of either a lack of meaningful involvement in extracurricular activities or involvement for an insufficient period of time and requires further investigation. Unfortunately, the magnitude of mental health problems of children and adolescents has not yet been recognised sufficiently by the policy makers in many countries [39]. Unexplained headaches, migraine and hypertension are becoming alarmingly common among teenagers – often an outcome of their stressful lives. Even recreational activities like sports, music, painting or swimming have become as competitive as studies [28]. In the present study, psychiatric problems are found to present in 32.6% of the participants, which is a serious an issue of concern for policy makers. A number of previous studies reported psychiatric illnesses among children [40, 41]. These students require immediate psychiatric attention for improving their mental health status – along with counseling for their parents. Academic stress is found to be positively correlated with parental pressure and psychiatric problems. Examination-related anxiety is also observed to be related to psychiatric problems. It is important to remember that mental constitution or coping capacities vary from one child to another. Therefore, children with poor coping capacities become more prone to anxiety, depression and fear of academic failure. The understanding of a child’s development has presently shifted from just a marks-based assessment to a holistic assessment of students’ performance in Kolkata schools because of numerous reported incidents of academic failure among students. Even schools affiliated to the WBBSE (West Bengal Board of Secondary Education), the State Board in Kolkata, India, have done away with ranks in report cards. In order to reduce academic stress on students and parents, since a decision in 2009 by the Human Resource Development Minister, the Government of India has made the Year 10 board examinations optional [42]. As a result, the CBSE has made the secondary examinations optional. While this policy has the potential to take some of the pressure of high school students, the intense competition means that many students still experience high levels of academic stress [43]. This study found that 63.5% of the students in the present study are stressed because of academic pressure. There were no significant differences in academic stress across gender, age, class, and other factors. Two-thirds of the students reported that their parents pressurize them for better academic performance. The incidence of reported parental pressure differed significantly by parental education levels, mother’s occupation, number of private tutors, and academic performance. More than four-fifths of students suffer from examination-related anxiety, especially female students and those who are not proficient in English. About one-third (32.6%) of the students are indicative of psychiatric caseness. In this regard, gender and father’s occupation were significantly associated. Academic stress was found to be positively correlated with parental pressure and psychiatric problems. Again, examination-related anxiety was positively related to psychiatric problems – which emphasises the need for psychological intervention. On the basis of the findings of the study, the following steps are suggested: • Immediate attention of mental health professionals is required for the students whose scores on the GHQ are indicative of psychiatric caseness for improving their mental health status.• At school, adolescents should be trained on how to manage stress and anxiety • Knowledge about mental health and academic stress should be promoted among the parents of the adolescents and taught strategies to help improve the resilience and coping strategies of their children.

4.1. Limitations of the Study

- Given the large population of the higher secondary students in Kolkata, the sample size was relatively small. Therefore, caution should be used when generalising the findings of the study. Secondly, responses are based on self-report. However, the findings give some idea about prevalence of the academic stress among higher secondary students in Kolkata and its association with parental pressure, number of private tutors and examination-related anxiety. To further validate the findings, another study with a larger sample is recommended. The present study did not take into account the effect of punishment or threat of punishment in schools on the mental health of the students – keeping in view the recently imposed blanket ban on corporal punishments in Indian schools, and also the fact that punishments are not usually deemed necessary in the Higher Secondary classes, as students are seen as mature enough to follow rules and regulations themselves. However, further investigation is needed to ascertain if the ban has been implemented effectively, and also to ascertain the impact of non-corporal punishments – such as scolding, suspension or withdrawal of facilities – on students. Finally while a strength of this study was that there was no or very little missing data in most of the variables, a limitation of the study was the high level of missing data for parental education, and occupation, and family income. The percentage of missing data in these variables ranged from 14.7% for fathers’ occupation to 28.9% for mothers’ occupation (Table 2). Missing rates were significantly higher among females, especially for Grade XI students or for those aged 16 or below. However, for the major outcome measures, most rates did not significantly differ between the groups indicating no great influence on inferential analyses. In conclusion this study examined the level of academic stress in year 12 high school students in Kolkata India. Nearly two-thirds of the students reported stress due to academic pressure – with no significant differences across gender, age, grade, and several other personal factors. Furthermore about two-thirds of the students reported feeling pressure from their parents for better academic performance. About one-thirds of the students were symptomatic of psychiatric caseness and 81.6% reported examination- related anxiety. Academic stress was positively correlated with parental pressure and psychiatric problems, while examination-related anxiety also was positively related to psychiatric problems. Given the high levels of academic stress and psychiatric caseness in this sample of high school students, there is an urgent need to develop suitable interventions to reduce this level of stress and psychiatric morbidity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors wish to acknowledge their gratitude to all the school authorities for giving permission for data collection. Students who participated in the study voluntarily and shared their valuable views and opinions about the issue also deserve special appreciation. Authors wish to extend special thank to Bishakha Majumdar for her assistance in data collection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML