-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(6): 201-207

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140406.03

Psychometric Properties and Diagnostic Utility of the 11-Item Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS-11) in Persian Samples

Mehrdad Shahidi1, Mahnaz Shojaee2

1PhD Student in Inter-University Doctoral Program, MSVU, Acadia U. and St. Francis, Xavier U. Halifax, Canada

2PhD Student in Measurement, Evaluation and Cognition Program, University of Alberta, Canada

Correspondence to: Mehrdad Shahidi, PhD Student in Inter-University Doctoral Program, MSVU, Acadia U. and St. Francis, Xavier U. Halifax, Canada.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The goal of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS- 11-item version) in Persian population. After translation and back translation of KADS and conducting a pilot evaluation, two major studies were conducted to answer four main psychometric questions. In the study 1, applying KADS-11 in 277 university students revealed a KADS-11 reliability of 0.88 that KADS-11 can determine two major factors including a Core Depressive Symptomatic factor and a Suicidal-Physical factor. Both factors have satisfactory internal consistency as well as all 11 items of KADS. Its reliability was 0.79 in pilot study and 0.88 in study 1. Using Zung Self-Rating Depressive Scale to obtain convergent validity, the study 1 revealed that both scales have high correlations in all parts. In the second study, 63 depressed patients from Shahid Dr. Lavasani Hospital and 40 normal individuals were selected to examine whether KADS has enough power to discriminate depressed individuals from non-depressed individuals. The analysis of data showed that the scale has enough power to differentiate depressed groups from non-depressed groups t (101) = 3.316, P <0.001. This sensitivity was proved for both factors, which extracted from varimax rotation in study 1.

Keywords: Kutcher Adolescents Depression Scale, Mental Health, Psychometric Properties, Diagnostic Tools

Cite this paper: Mehrdad Shahidi, Mahnaz Shojaee, Psychometric Properties and Diagnostic Utility of the 11-Item Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS-11) in Persian Samples, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 201-207. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140406.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The diagnosis of Depression refers to a set of different but integrated symptoms, signs and associated functional impairment that represents a unique clinical picture by which individuals are differentiated and characterized as having a disorder distinct from usual negative emotional states. Low mood, negative cognitions and withdrawn behaviors are predominant components of this clinical picture (Kutcher & Chehil, 2008) that also serve to distinguish this disorder from other mood disorders as described in ICD-10 (Thapar, Collishaw, Potter, & Thapar, 2010) and DSM V (2013). Following these clinical criteria, clinicians evaluate numerous symptoms including sadness, worthlessness, hopelessness, low energy, feeling worried, low weight, dysphoric mood, suicidal thoughts, feeling fatigued, sleep disturbance, and losing interest to assess and measure depression (Brooks, Krulewicz, & Kutcher, 2003; Bachner, O'Rourke, Goldfracht, Bech, & Ayalon, 2013; Thapar et al., 2010).Revealing cognitive, affective, behavioral, and somatic dimensions of Depression, the above-noted symptoms are also recognized as the main components of various diagnostic and screening instruments by which clinicians attempt to identify and measure Depression and record its intensity during clinical care. This is often done with the application of specific Depression scales, which are tools that can assist clinicians in identification, diagnosis, severity evaluation and change over time of the various syndromal components of Depression. Since Depression commonly onsets in young people and causes other mental impairments (Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Wilkinson, Croudace, & Goodyer, 2013; MacMaster, Carrey, & Langevin, 2013), it is important that tools be available to assist clinicians in diagnosis and care of Depression in this population. A variety of Depression scales have been developed, validated and deployed in this population, and a number of key features pertaining to their clinical utility have been identified (Levine, 2013; Roberge, Dore, Menear, Chartrand, Ciampi, Duhoux, & Fournier, 2013; Brooks et al., 2003; Trujols, Feliu-Soler, Diego-Adeliño, Portella, Cebrià, Soler, Puigdemont, Álvarez, & Perez, 2013). There are:1) Ease of administration and the number of items 2) Number of items3) The ability to distinguish comorbid symptoms4) Specificity and sensitivity5) Purpose: screening or diagnosis6) Ability to measure change over time (treatment sensitivity)7) Internal reliability and validity8) Developmentally appropriate9) Self report rather than clinician administered 10) Easily electronically available at no costFor comprehensive clinical care of Depression in adolescents and young adults, it is important to be able to utilize tools that address many of above domains. Thus, some commonly utilized scales may have little clinical utility as they do not do so. For example, Dimensions of Depression Profile for Children and Adolescents (DDPCA: Qualter, Brown, Munn, & Rotenberg, 2010) is a successful tool at identifying individuals who are at high risk of suicide (Qualter, et al., 2010), but it has low sensitivity to the change of symptoms during the treatment.Some diagnostic scales (such as the 21–item Beck Depression Inventory: BDI) are made up of numerous items and take a relatively long time to complete, making them less appealing to teenagers. Others (such as the 21–item Children’s Depression Inventory: CDI; the 21-BDI and Center for Epidemiology Depression Scale: CES-D) have low discriminative validity in adolescent Depression (Brooks & Kutcher, 2001). Others, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-HADS-FC (Roberge, et al., 2013) have low sensitivity to age and developmental trajectories or (the CES-D and the Mood and Feeling Questionnaire) are applied as screening tools (Levine, 2013; Thapar et al., 2010). The PHQ-9 has been adapted for adolescents use but concerns about its sensitivity (about 50 percent) have been noted (Allqaier, Pietsch, Fruhe, Sigl-Glockner, & Schulte-Kome, 2012), and it has been primarily suggested for screening purposes.Amongst the many different diagnostic and screening scales available for adolescent depression, the Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS-11-item version) is a unique self-report tool that provides clinicians with various advantages (Brooks & Kutcher, 2001; Brooks, e al., 2003; LeBlanc, Almudevar, Brooks, & Kutcher 2002), and it addresses most of the domains identified above. The KADS-11 can be used to identify and diagnose depressed adolescents and is sensitive to treatment effects, thus promoting monitoring over time. It is easy and time efficient in its administration and has high diagnostic validity with good sensitivity and specificity for adolescent Depression (Brooks & Kutcher, 2001; Brooks et al., 2003).In addition to above noted characteristics, the KADS-11 is developmentally appropriate and was derived from the core symptoms of adolescent Depression, and it also measures the severity of those symptoms (Brooks et al., 2003). Thus, it makes it a useful clinical tool in the diagnosis and management of adolescent Depression.To evaluate the clinical utility and acceptability of use of KADS-11 in Iran, the authors decided to assess the psychometric properties of the KADS-11 in appropriate Iranian adolescent and young adult samples. This also allowed for the opportunity to compare the psychometric properties of the KADS-11 with Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale which is commonly used in Iran (Makaremi, 1992; Shojaeizadeh & Rasafiyani, 2001; Ghanei, R., Golkar, F., & Edalat Aminpour, E., 2014)The aims of this study was a) to confirm the factor structure of KADS-11 in Iranian samples, b) to determine the internal consistency and split-half reliability of KADS-11, c) to verify the power of KADS-11 to differentiate depressed individuals from non-depressed persons, and d) to determine whether KADS-11 is a good measure of different components of depression for Iranian samples. To reach these aims, a pilot study was conducted to confirm the Persian translation of KADS and to obtain its primary reliability. In this stage translation and back translation was independently conducted by two expert reviewers, both fluently bilingual in English and Farsi. Following confirmation of translation accuracy, the KADS-11 was then applied in 50 randomly selected university students to determine test/retest reliability (0.79) over a period of 10 days. Following this pilot phase, two sequential studies further were carried out.

2. Study 1

- Study one focused on the reliability, construct validity and criterion validity (using parallel test) of KADS-11. Although, previous studies of KADS-11 were not focused on factor analysis, in current study factor analysis was also used to extract any probable factors for KADS-11.

2.1. Method (Study 1)

- ParticipantsStudy one involved a total of 300 students of Islamic Azad University-Tehran Central. Of this group of participants, 23 individuals were excluded because of incomplete responses to the scale. Therefore, data was analyzed using 277 completed scales. The subjects were selected randomly by using a systematic multistage random sampling method. This method consists of several systematic stages briefly including 1) identifying and providing the frame of sampling for on campus classes, 2) identifying a list of all on campus classes based on various disciplines, 3) selecting several classes from stage 2 randomly, and calculating the total population, 4) going to the selected classes based on stage 3 with the instructors’ permission, 5) using simple random ways to choose students in each class until reaching the expected sample size, 6) describing the goals of research, emphasizing confidentiality of answers and explaining the ethical issues to potential participant, 7) administrating the scales and questionnaires to the selected students in group sessions in their usual classes.Of total sample students, 22 (8%) individuals were males and 255 (92%) were females. The different numbers of samples aligned with the nature of university (Valiaser Campus) population in which female students consist of approximately 80% of the total student population. The proportional discrepancy between female and male students in Iranian universities is mostly based on women’s cultural preferences and university admission policy by which female students are remarkably more than male students (Rezai-Rashti, 2012; World Bank Middle East and North Africa Social and Economic Development Group, 2009). The mean age of sample students was 22.8 years (SD = 4.38). Since recent studies revealed that the age of adolescence is socially and culturally contextual, and it is adjacent to the age of young adults (Edberg, 2011; Encyclopedia Britannica, 2014), and because late adolescence has been characterized differently by age (17 to 20 years-Nicholas, 2008; 18 to 22 years-Santrock, Mackenzie, Leung, & Malcomson, 2005), the researchers decided to focus on late adolescence (18 to 22 years-Santrock et al., 2005), and also young adults.

2.2. Instruments

- In this study, two scales as well as a few demographic questions were used.Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (ZUNG) The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale is a 20-item self-administered survey to quantify the depressed mood of individuals. It is not a youth orientated scale. According to Romera, Delgado-Cohen, Perez, Caballero, and Gilaberte, (2008), this 20-item scale along with 4 subscales (core depressive factor; cognitive factor, anxiety factor and somatic factor) is scored in four categories from normal range to above severely depressed range. Using for adolescents 18 years of age and over, the scale has been deemed to be appropriate for both inpatient and outpatient use. A total score of this scale is derived by summing the individual item scores (1–4) and ranges from 20 to 80. The items are scored: 1 = a little of the time, through 4 = most of the time, except for items 2, 5, 6, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, and 20 which are scored inversely (4 = a little of the time). Although in this study the previously demonstrated to be reliable Iranian version of Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale was used, we repeated the Cronbach's Alpha and obtained a reliability coefficient of 0.77. Focusing on this coefficient, this scale was then used as a parallel test in analyzing the validity of KADS-11.Kutcher Adolescents Depression Scale: eleven item version (KADS-11)The KADS-11 is an eleven-item, self-report instrument developed and initially was studied in a Canadian population (Brooks & Kutcher, 2001; Brooks, et al., 2003; LeBlanc, et al., 2002). This scale was introduced for clinical practice as a sensitive and specific instrument to aid in diagnosis and to monitor the change in severity of symptoms during the course of treatment. KADS-11 was created using youth friendly language. It is sensitive to symptom change during treatment, and it is easily and quickly completed, diagnostically valid and demonstrates high reliability (Brooks & Kutcher, 2001; Brooks et al., 2003).KADS’ items were constructed on the basis of core symptoms of depression that measures the frequency of depressive symptoms (Brooks et al., 2003). Although KADS’ validity and reliability have been demonstrated in several Canadian studies, we analyzed its internal reliability (Chronbach’s alpha of 0.79) in our first pilot study in Iran and thus deemed it satisfactory to proceed with study 1.

2.3. Procedure

- The group of 277 students, described above, completed both the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung-DS) and the Kutcher Adolescents Depression Scale 11-item version (KADS-11) in group sessions in their usual classes based on the sampling method described above. Administration of the instruments was counterbalanced. Participants took approximately 5 to 15 minutes to fill in both of scales.

2.4. Results (Study 1)

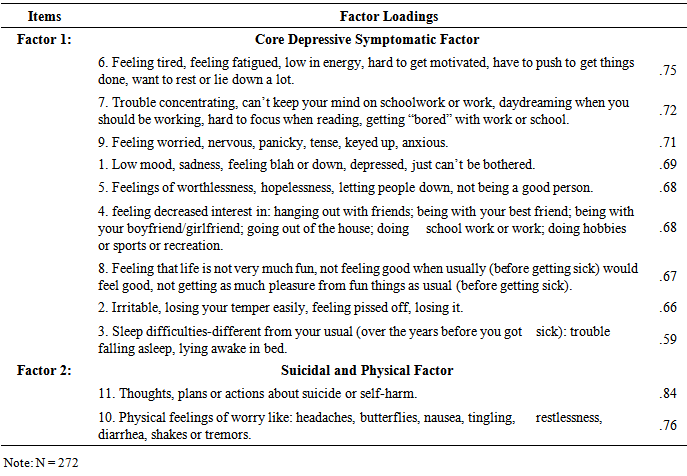

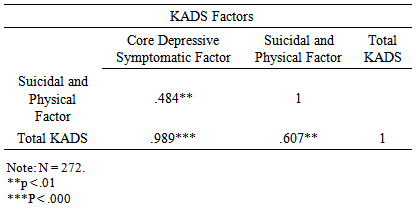

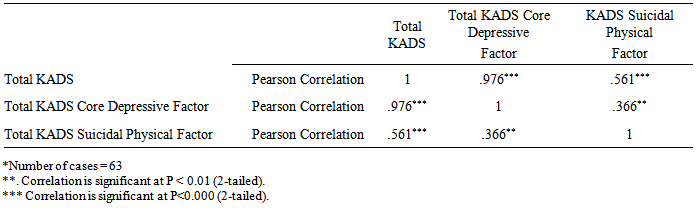

- Factor Analyses (Construct Validity)The correlation of matrix of the 11 items was subjected to principal component analysis and varimax rotation. The researchers used the following criterion to select the items for a factor: an item had to load at least 0.40 on its own factor but less than 0.40 on any other factor. Since Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO and Bartlett’s test) was fully satisfactory significant (0.91, P < 0.000), the researchers continued factor analysis. After varimax rotation, two factors were extracted. These factors could explain 55.20% of total variance and proved to be the maximum number interpretable. Scrutinizing all items in both factors led researchers to identified the extracted factors as (a) Core Depressive Symptomatic Factor (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) and (b) Suicidal and Physical Factor (items 10 and 11). The results are presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

3. Study 2

- The power of the KADS-11 in discriminating clinically depressed individuals from non-depressed persons was a main question in this research. To determine this sensitivity, the researchers tended to conduct a second study (study 2) that was focused particularly on depressed patients who were diagnosed and hospitalized for a short time in Shahid Dr. Lavasani Hospital, which is located in eastern area of Tehran, Iran. This hospital has different specialized wards including general surgery, CCU, ICU, Heart Surgery, and a Psychiatric ward. Of 275 beds in this hospital 90 beds are designated for psychiatric patients.

3.1. Method (Study 2)

- ParticipantsNo participants from previous studies took part in study 2. Two distinct groups of subjects were studied in study 2. The first group was made up of 63 depressed patients who were visited and interviewed by one psychiatrist and one clinical psychologist at the hospital. They were hospitalized from 20 to 30 days after the primary diagnosis determined by clinical interview based on DSM V (2013) was made conjointly by the interview. Of this group, 30 individuals (47.6%) were female and 33 (52.4%) were male. The age mean was 23.41 (SD=2.248). The second group was made up of 40 subjects selected randomly from the same student population (students at Valiaser Campus) in which the KADS-11 had been evaluated in study 1. There was no overlap amongst any participants across studies. Thirty five subjects (87.5%) were female and five (12.5%) were male. This percentage was similar to sexual distribution of the Valiaser Campus population. The mean age of this group was 21.00 (SD = 1.908).Procedure Regarding the first (depressed) group, researchers asked two specialists (psychiatrist, psychologist) attending at the psychiatric ward in the hospital to apply the KADS-11 with their patients after they had made their primary diagnosis. Patients were blind to their diagnosis at the time they completed the scale. The second group (control) was asked to complete the KADS-11 in their usual classroom based on sampling method previously described.

3.2. Results (Study 2)

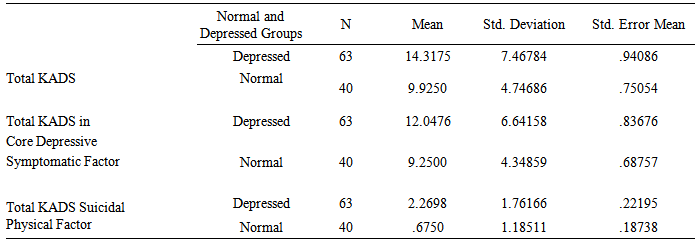

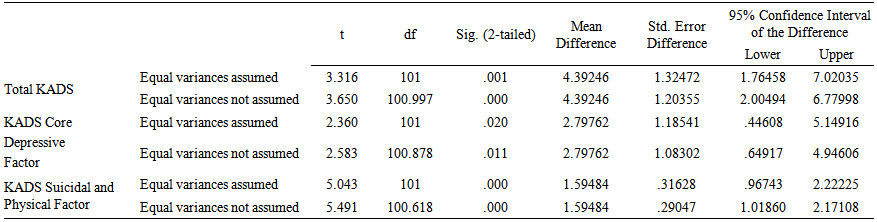

- The analysis of data revealed that the mean KADS-11score in depressed group (M = 14.32, SD =7.47) was higher than the mean of KADS-11 in control group (M = 9.93, SD = 4.75). The mean analysis for the two factors of KADS-11 (Core Depressive Symptomatic factor and Suicidal-Physical factor) showed similar results (Table 4).

|

|

| Table 6. T. Difference between Depressed Group and Normal Group in terms of KADS-11 |

4. Discussion

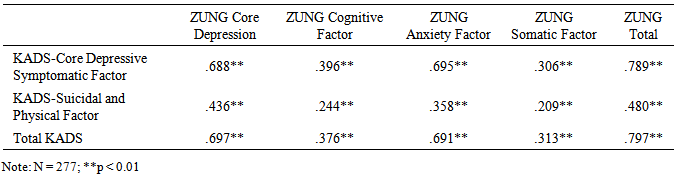

- The principal aim of this study was the analysis of psychometric properties of the KADS-11 in a youthful Iranian population. The psychometric properties of this scale in native Persian-speaking samples demonstrated that the KADS-11 could be useful and psychometrically appropriate tool for clinical care in the assessment and diagnosis of Depression in young people living in Iran. Additionally, the KADS-11 was specifically developed for use with young people and meets each of the 10 tool use criteria items identified above. The first goal of this study was to evaluate the internal consistency and factor structure of KADS-11. The factorial analysis revealed two specific factors: the Core Symptomatic Depressive factor and the Suicidal-Physical factor. The first factor shows that most KADS-11 items (9 items) deal with cognitive, emotional, mood and behavioral symptoms of depression. This analysis also showed that the KADS-11 is an appropriate scale to use clinically to diagnose depression and evaluate the severity of symptoms in Persian samples. Although the number of items in second factor (Suicidal-Physical factor) was remarkably low, the content of both items 10 and 11 demonstrated significantly power to identify those who demonstrate suicidality. Revealing satisfactory internal consistency and criterion validity, as well as good sensitivity, we thus conclude that the KADS-11 is clinically useful and appropriate scale to be used in psychiatric and psychological settings in Iran. The high and significant correlation between the KADS-11 and Zung Self-Rating Depressive scale demonstrated that KADS-11 is not only consistently valid, but also has better psychometric properties and is much shorter and thus may be considered for use in place of Zung’s Depressive Scale. In both studies (Study 1 and 2), the researchers focused on the age range of late adolescence (18 to 22 years old and 22 to 29 years respectively). As the prevalence of Depression in this age group approaches six percent, the clinical application of KADS-11 should be considered when health providers are evaluating Iranian youth for emotional, cognitive and behavioral challenges that may be associated with Depression. Since the estimated current population of Iran is about 78 million people, and 24.1% of this population are aged between 0 and 14 years and 16.0% are aged between 15 and 24 years (Worldmeters, 2014), routine application of the KADS-11 in primary health care settings should be encouraged. This scale is particularly reliable for Iranian population who are in late adolescence (18 to 22 years-Santrock et al., 2005) as well as for young adults. The public and population health impacts of this suggestion may be the focus of future research. Additionally, we are considering future studies further addressing KADS-11 sensitivity to external criteria of depression severity (such as functional impairment), its sensitivity to symptom changes during the treatment in this population as well as more detailed analysis of the relationship between KADS-11 scores and male or female sex in more equally balanced samples.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- In this study, the researchers would like to appreciate Dr. Stan Kutcher (A Distinguished Professor at the Department of Psychiatry, Dalhousie University, Canada) who provided the permission for the use of KADS-11 in this work and particularly for his review of this manuscript. We also thank Dr. Hosein Khedmatgozar (a university lecturer and the clinician at Shahid Dr. Lavasani Hospital), and all other clinicians at the hospital who kindly helped us. We are also pleased to thank all students at Valiaser Campus, IAU-TC. This research was not funded by any institution and we have no financial disclosures to report.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML