-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(6): 193-200

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140406.02

Psychometric Properties of the Croatian Version of Pavlov’s Temperament Survey for Preschool Children

Sanja Tatalović Vorkapić1, Ivana Lučev2

1Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia

2Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

Correspondence to: Sanja Tatalović Vorkapić, Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Croatian version of Pavlov’s Temperament survey for children was created and validated in this study. N = 245 pre-school teachers (all female) provided estimates on this scale for a total of N = 4256 children (2121 girls and 2135 boys) with mean age M = 4.59 (SD = 1.289). As it was expected, factor analysis on principal components with Varimax rotation revealed that three-factor solution is the most interpretable. Overall, three components explained 36.84% of the total variance. Reliability levels Cronbach alpha for Strength of excitation, Strength of inhibition and Mobility are very satisfying. Descriptive for subscales, their intercorrelations and gender differences have mostly confirmed earlier findings on adults. Results indicate the scale can be considered a useful and reliable tool for measuring Pavlovian temperament characteristics of children, however, future verifications on different samples of raters should be conducted.

Keywords: Pavlov’s temperament survey, Preschool children, Validation, Reliability

Cite this paper: Sanja Tatalović Vorkapić, Ivana Lučev, Psychometric Properties of the Croatian Version of Pavlov’s Temperament Survey for Preschool Children, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 193-200. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140406.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- There are two main reasons why a new child temperament observation scale should be constructed in Croatia. Firstly, reliable, valid, objective and theoretically grounded temperament scales for children in Croatian are scarce. Secondly, Strelau’s conceptualization of temperament based on CNS-properties (1983) with its pronounced developmental aspect lends itself well to development of instrument intended to measure characteristics of children. This would also be the first Pavlovian child temperament survey, as all versions of the PTS created so far were intended for adults. “Temperament refers to basic, relatively stable personality traits, which have been present since early childhood, occur in man, and have their counterparts in animals. Being primarily determined by inborn neurobiochemical mechanisms, temperament is subject to slow changes caused by maturation and individual-specific genotype-environment interplay” (Strelau, 2001, p. 312.). Temperament represents stylistic, formal behavioural characteristics (Strelau, Angleitner & Newberry, 1999). Also, these relatively stable individual differences manifest early in life and are largely biologically determined (Newberry, Clark, Crawford, Strelau, Angleitner, Jones & Eliasz, 1997). Since different temperament definitions mention early childhood, it is expected to observe these stable individual differences early in life (Rothbart & Bates, 1998; Rothbart & Derryberry, 2002). Therefore, it would be interesting to be able to measure them early and explore stability of temperament dimensions over time. With instruments that could asses Pavlovian temperament dimensions in children it would be possible to carry out developmental and longitudinal research of temperament as it is operationalized within Strelau’s theory.Besides only one EAS-research conducted in Croatia (Sindik & Basta-Frljić, 2008), a systematic and valid development of an observation scale for toddlers and (pre)scholars could enable exploration of individual differences in strength of excitation, strength of inhibition and mobility of children. Instruments for appraisal of child temperament often consist from items describing different behaviours, which are estimated for frequency by teachers, or parents who are able to observe the child (Zupančič, Fekonja & Kavčič, 2003). The junior PTS scale was constructed as a checklist of behaviours based on the dimensions (the defining components) of the three Pavlovian temperament characteristics. Strelau (1983) formed one of the most influential temperament theories that encompassed Pavlov’s basic CNS-properties (strength of excitation, strength of inhibition, mobility and balance). These represent the neurophysiologic characteristics, which underlie individual differences in behaviour (Gray, 1964; Corr, 2007). Different configurations of the CNS-properties result in different types of CNS and they present the physiological basis of temperament (Strelau et al., 1999). CNS properties have been conceived with focus on the individual’s ability to adapt (Strelau, Angleitner & Ruch, 1990). Thus, strength of excitation (SE) refers to the functional capacity of the nervous system that reflects in the ability to endure intense or long-lasting stimulation without development of protective or transmarginal inhibition. In other words, SE represents efficiency in conditions of high level of stimulation and preference for such situations. Since individuals in their everyday lives are confronted with stimuli of great intensity, Pavlov (1951-1952) considered SE to be the most important CNS-property. Strength of inhibition (SI) refers to conditioned inhibition and the ability to maintain a state of conditioned inhibition. In behavioural terms, it represents the person’s ability to stop or delay a given behaviour and to refrain from certain behaviours and reactions when required (Tatalović Vorkapić, 2010). Mobility of nervous processes (MO) manifests in the ability to quickly and adequately react to changes in the environment. Mobility refers to the ability to give way -according to the external conditions, to give priority to one impulse before the other (Pavlov, 1951-1952). The last CNS-property is balance of nervous system (BA) or equilibrium which is defined as the ratio of strength of excitation and strength of inhibition. The functional meaning of BA consists of the ability to inhibit certain excitations when required in order to evoke other reactions according to the demands of the surroundings.The measurement scale that has been constructed and validated within the frame of Strelau temperament theory is the Pavlovian Temperament Survey (PTS) that was constructed for cross−cultural comparison of the Pavlovian dimensions of temperament. It consists of three subscales: Strength of Excitation (SE), measuring the efficiency in conditions of high levels of stimulation and preference for such situations; Strength of Inhibition (SI), referring to the ability to stop or delay a given behaviour and to refrain from certain behaviours and reactions when required; and Mobility (MO), measuring the ability to quickly and adequately react to changes in the environment (Strelau, 1983; Strelau et al., 1990). This questionnaire was originally intended for measuring individual differences in CNS-dimensions in adolescents and adults. Temperament traits are considered universal for all human beings regardless of their specific cultural environment (Strelau et al., 1999). However, behaviours in which these dimensions manifest can be, and indeed often are somewhat culturally specific. In order to obtain valid measures of universal temperament dimensions that would include items that refer to behaviours relevant for expression of temperament traits in particular language and culture, Strelau and his colleagues (1999) devised specific procedure for construction of different language versions of Pavlovian temperament survey. They determined definitional components that refer to different aspects of the three PTS scales: 7 for SE (such as “The individual is prone to undertake activity under highly stimulating conditions” and “Under conditions of high stimulative value, the individuals performance does not decrease significantly”) and 5 each for SI (“The individual easily refrains from behaviour which for social reasons is not expected or desired” and “If circumstances require, the individual is able to delay his/her reaction to acting stimuli”), and MO scale (“The individual reacts adequately to unexpected changes in the environment”, “The individual prefers situations which require him/her to perform different activities simultaneously”). These definitional components were a starting point for generating universal pool of items. For each new language version, these items are translated and administered to a sufficiently large number of participants and items that most coherently represent temperament dimensions are selected for the final version of the instrument. Croatian version of the PTS was constructed in 2002 (Lučev, Tadinac-Babić, & Tatalović, 2002). It consists of 69 items (23 for each dimension) and represents all of the defining components of the PTS. Total of 414 participants (134 males and 280 females), students of Universities in Zagreb and Rijeka, their family and friends were included in the construction sample. Age span of participants was between 16 and 85 (M = 22). Validation sample consisted of 101 male and 362 female university and high school students from Zagreb and Rijeka, 17−26 years old (M = 18) (Lučev, Tadinac, & Tatalović Vorkapić, 2006). Cronbach α coefficients determined in the construction and validation study were αSE = .87, αSI = .81, αMO = .88, and αSE = .80, αSI = .79, αMO = .83, respectively (Lučev et al., 2002; Lučev et al., 2006) and were similar to those obtained in some recent studies (Tatalović Vorkapić, 2010; Tatalović Vorkapić, Lučev & Tadinac, 2012; Tatalović Vorkapić, Tadinac & Lučev, 2013). The established factor structure was comparable to those established for other versions of PTS (Bodunov, 1993) and in accordance with the theoretical concept: three oblique factors that could be interpreted as SE, SI and MO (Lučev at al., 2006). Similar psychometric properties that are found for different language versions of PTS and comparable correlations between scales indicate that parallel versions of PTS measure universal temperamental traits the way original authors of this instrument intended.Worldwide, several different scales and measures have investigated child temperament, which has been used both: rating from parents and teachers. The most applied are EASI (Buss & Plomin, 1986), Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (Putnam & Rothbart, 2006) and Inventory of Child Individual Differences (Halverson et al., 2003). Even though today is a major breakthrough in the study of temperament in the light of refinement of basic dimensions of temperament (Rothbart, 2004), there are still various disagreements concerning the number of dimensions, unique theoretical frame and methodological problems related to subjectivity of those who rate children's behaviour (Zupančić, 2008).In addition to previous children’s temperament research, the purpose of this study was to construct a set of items based on the definitional components of the original PTS scales that would encompass behaviours of children reflecting Pavlovian temperament dimensions. With a procedure analogue to the one described above we than administered these items to a large enough sample of participants and selected items that will be representative for expression of PTS dimensions that can be observed in children that live in Croatia.

2. The Aim of the Study

- Since different versions of the PTS for adults show satisfactory psychometric properties, it would be interesting to create an instrument that will enable exploration of the individual differences in strength of excitation, strength of inhibition and mobility of children. The empirical data could present a basis for further elaboration of the existing Strelau temperament theory. PTS instrument for assessing temperament of children would enable researchers to carry out longitudinal studies and explore the development of three CNS-dimensions. Therefore, the main contributions of this research are: 1) gathering data on development of temperament dimensions that would enable verification and elaboration of the Strelau temperament theory; 2) creating an objective and valid instrument for assessing child temperament in Croatia. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to develop Pavlov’s Temperament Survey for Preschool children in Croatia and to analyze its psychometric properties, such as reliability, factor structure and validity. Considering the fact that temperament represents stylistic, formal behavioural characteristics (Strelau et al., 1999), which manifest early in life and are largely biologically determined (Newberry et al., 1997), it is expected to determine previously described three CNS-properties in th sample of chldren, too.

2.1. Participants

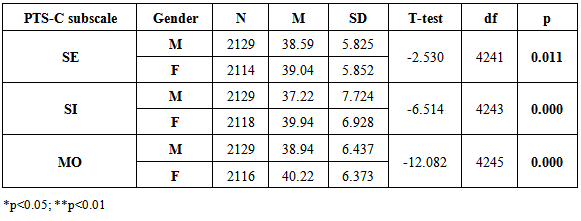

- In this study, a sample of N=245 pre-school teachers (all female) were providing estimates on the Pavlovian Temperament Survey for a total of N=4256 children (2121 girls and 2135 boys) with mean age M=4.59 (SD=1.289) and age range between 1 and 7 years. Children were selected through a process of cluster sampling. For the purposes of this study, early and preschool institutions were selected randomly from three counties: the Primorsko-goranska, Istarska and Zagreb County. Then forty-five of kindergartens were randomly selected and all of the educators employed were asked to participate in the study. All children in mixed and nursery educational groups that were led by preschool teachers who agreed to participate in this study were assessed. In average, one educator evaluated 16 children in her educational group, with number of children in the groups ranging from 8 to 26 children. Some other variables, such as socio-economic status, genetics or some other individual differences of children were not controlled, since their effect on this sample size would be small. For example, this assumption about high level of sample homogeneity has its background in the fact that only employed parents could enroll their children in the kindergarten in our country, what equalized them according to their socio-economic status.

2.2. Measuring Instrument

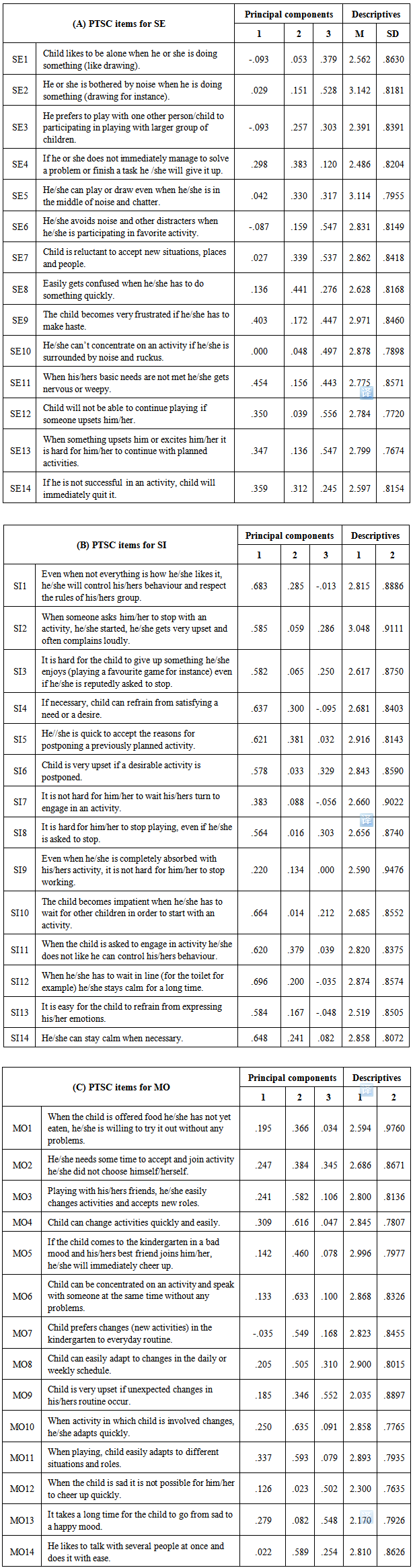

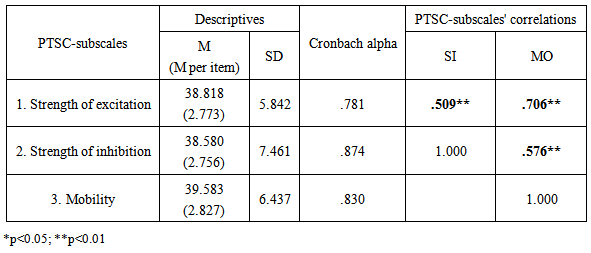

- The instrument that was constructed in the scope of this study was based on the Pavlovian temperament dimensions and primarily intended for assessment of pre-school and grammar school children. Items were constructed based on the definitional components of the three Pavlovian Temperament Survey scales by the two investigators and then modified according to suggestions of the three educators that work with pre-school children. 48 items that were deemed understandable and pertaining to the observable behaviours of children were kept in the starting item-pool. For each item, person observing the child rates how frequently the child behaves in a described way on the scale of four points: 1-never, 2-rarely, 3-often, 4-always. Items for the final version were selected according to the procedure described by the original authors of the Pavlovian Temperament Survey (Strelau et al., 1999), and items that were deemed relevant measures of the three dimensions of temperament were included in the final version of the Pavlovian Child Temperament Scale. Items that had correlations with total result in the scale lower than 0.3 and items with higher correlation with one of the scales they did not belong to than with the scale they were intended for were excluded. Final version of the instrument consists of 42 items, 14 for each of three PTS scales. Internal consistency of the constructed instrument was satisfactory, the Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients were 0.78 for SE, 0.87 for SI and 0.83 for MO scale (Table 2).

2.3. Procedure

- Data was collected in kindergartens of three Croatian counties: Primorsko-goranska, Istarska and Zagreb. Cities and pre-school education centres were selected at random. Part of the sample (N=42) that consisted of pre-school educators that were students at the Department of pre-school education at the University of Rijeka were trained in application of the questionnaire and they collected data from five other pre-school educators. The other part of the estimators (N=203) was collected as a form of a cluster-sample. It took about 15 minutes to fulfil the questionnaire. Before the collection of data started, permissions were obtained from all institutions and parents of the children were informed. Preschool educators that were participating in the study were told the research is voluntary and anonymous and only children whose parents consented to the study should be included. They were also instructed to assess only children who are in the groups they normally work with, and that all the children should be. Each educator and each child assessed was given a code in other to ensure anonymity of data. The instruction to the educators assessing the temperament of children was “Before you is a scale on which you should assess frequency of the behaviour described for each child in your group. You should asses the children one-by-one, after 3 to 5 days of observation. If you worked for a long time with this group of children, even less time for observation should be needed. Do not try to asses all the children in the group at one time, but fulfil the questionnaire for a third of the children on the first day, for second third on the second day and rest of the children the third day. After you did that, make sure you assessed the frequency of the behaviour on each item and for all children. The results of the study will be reported to all the pre-school institutions that participated in the research. We thank you for your cooperation.” Data were collected during period of three months.

3. Results and Discussion

- After we selected items for the final version of the Pavlovian Temperament child Survey, we conducted the reliability analysis. All three scales showed satisfactory levels of internal consistency (Table 2) that were comparable to the results for adult Croatian version of the PTS (Lučev et al., 2002; Lučev et al., 2006; Lučev, 2007) and other versions of the PTS (Strelau et al, 1999). SI and MO scale in particular show good reliability (alpha .83 and .87, respectively) and their items represent all definitional components they are supposed to cover (5 each). SE scale had acceptable reliability (α=.78), but there were some problems in the construction of the SE scale based on the data collected on the child Pavlovian temperament survey construction sample. Although we followed the procedure described above that was envisioned by the original authors of the PTS that had yielded numerous psychometrically valid instruments that are comparable in both reliability levels and factor structure, 14 items of the SE scale represent only 4 out of 7 definitional components that the Strength of excitation is comprised of. It is not necessary for the PTS scales to have items that cover all theoretical dimensions (although it would be ideal if they had), in fact, some of the different adult language versions do not cover all the definitional components (see Strelau et al., 1999). If we inspect closer the items of the child temperament scale we can determine that more than half of them belong to the SE2 definitional component, “The individual is prone to undertake activity under highly stimulating conditions” and that there are no items from the SE1 (“Threatening conditions do not stop the individual from undertaking previously planned activities”), SE5 (Under conditions of high stimulative value the individuals performance does not decrease significantly) and SE6 facets (The individual is resistant to fatigue when engaging in long lasting activity). Our sample of raters were all pre-school educators who are responsible for the safety of the children in their care, and they might view activities under threatening conditions as unacceptable, maybe even more so than parents. That will of course affect their answers and correlations between items, influencing the levels of internal consistency and the process of selection of items for the final version of the instrument. SE2 could be considered core aspect of the Strength of excitation scale, and it is not inherently wrong to have so many of the SE items reflect this definitional component, it is not a threat to the content validity, however disbalance of definitional components representations is probably contributing to problems with construct validity. Although the instrument we developed shows promise as a useful and reliable tool for measuring Pavlovian temperament characteristics of children, a verification on different samples of raters should be conducted, as well as a construction of modified scale on construction sample of parents assessing their children. It could be that the definitional components that are a legitimate part of temperament and have proven as a valid way to measure temperament of adults are seen as something very undesirable by the pre-school educators and it might be influencing the results.Both Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure and Bartlett test of sphericity were significant (KMO=0.949; Chi2=56168.33, df=861, p<0.00) indicating the dataset was suitable for factor analysis. We conducted factor analysis on the level of items with the principal components method, and table of loadings we show here is form a Varimax rotation as it was the most interpretable solution. Also, the Scree-plot has confirmed that the three-factor solution is the most interpretable in this study. As can be seen in the Table 1, the clearest situation was in the case of the second component which explained 6.88% of the total variance and had loadings higher than 0.3 with all of the mobility items and could therefore be interpreted as a mobility factor, although it also had loadings higher than 0.3 with 4 of the SE and 3 of the SI items.The first component explained 24.68% of the variance and it had significant loadings with all but one SI item (that item, t27, had loadings lower than 0.3 with all three components), but also with 5 SE and 2 MO items. Third component explained 5.28% of the variance and had significant loadings 11 (out of 14) SE items, but also with 1 SI and 6 MO items. The factor structure is not nearly as clear as one would deem ideal, but the components could be interpreted as Strength of excitation (component 3), Strength of inhibition (component 1) and Mobility (component 2). Other studies performed factor analysis on the level of facets (Bodunov, 1993; Lučev et al., 2006) but on our sample the factor solution on the level of facets was even less interpretable, probably due to the problems with SE scale that were mentioned earlier.We atempted to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis with AMOS, testing our model of three scales consistent of 14 items each, however for the model to fit according to the AMOS criteria, we would have to reject more than half of the items, and possibly even one of the scales, which would not yield a desired measure of Pavlovian temperament dimensions for children.

|

3.1. Reliability of the Instrument and Descriptive Statistics for the Scales

- The group averages for three PTS-dimensions (Table 2): Strength of excitation (M=38.8; SD=5.84, M-per item=2.77), Strength of inhibition (M=38.6; SD=7.46, M-per item=2.76) and Mobility (M=39.6; SD=6.58, M-per item=2.83) did not substantially differ from the results obtained on the Croatian standardization sample (Lučev et al., 2002) and other adult samples collected with Croatian PTS (Lučev et al., 2006, Tatalović Vorkapić et al., 2012). In order to compare averages on the different versions of PTS scales M-per item is applied since these instruments differe in number of items (Strelau et al, 1999). Average for SE scale was a bit higher from the averages obtained for different adult samples in Croatia (2.42-2.53) (Tatalović Vorkapić et al, 2012) but in the span of average values in other countries (2.25-2.48) (Strelau et al, 1999). Not much is known about the changes in the Pavlovian temperament dimensions, and empirical data on correlations of age and PTS scales is ambiguous (Strelau, et al., 1999, Lučev et al., 2002). Future studies with PTS-C on children of different ages should reveal weather significant developmental changes in Pavlovian dimensions exist at an early age.Distributions of results on PTS scales were not significantly different from normal distribution, and we could justly apply parametric statistical procedures on this sample of data. All intercorrelations found between PTS-dimensions were statistically significant (see Table 2) and in agreement with results of other studies with PTS (Strelau et al., 1999). All PTS-dimensions correlate positively with each other, with the highest correlation between strength of excitation and mobility. Individuals with higher levels of strength of excitation also have more pronounced strength of inhibition, as well as higher results on mobility, which is in accordance with the Strelau's theoretical model (1983). However, intercorrelation between scales of PTS-C we can see in Table 2 is slightly higher than those recorded for adult scales so far (Strelau et al, 1999; Lučev et al., 2002; Tatalović Vorkapić et al., 2012).

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The main purpose of this study was to create Pavlovian Temperament Survey for pre-school children and examine validity of the instrument. As it was expected, previously described theoretical model and three PTS-dimensions were confirmed in this sample of preschool children. The PTS measure of child temperament is easy to apply and can serve as informative tool for those who work with pre-school children as well as in scientific studies of early development of temperament traits. Preschool educators can: a) plan work with children on individual and group level adapted to their specific temperament profile; b) inform parents on the objective indicators of their child’s development; c) have an objective measure of temperament that enables them to document the development of children d) create different preventive and early intervening programs for preschool children. Also, PTS junior could serve as a solid tool for various developmental and longitudinal research in the field of a child temperament.The construction sample was rather large and it would seem that the Pavlovian Child Temperament Survey is exhibiting good reliability. Nevertheless, some study limitations should be taken into consideration in future research in the field of children temperament. In this study, data collection included only children who attend kindergartens, what is not relevant if serious verification of PTS theoretical model will be carried out. Therefore, another type of sampling should be used in future research. Also, since some other relevant factors were not controlled, such as socio-economic status, genetics, and other individual differences between children with some family characteristics, the research should be run again having in mind these variables. So, in future studies, PTS-c should be revalidated on different samples of raters, including both preschool teachers and parents and norms should be determined for different ages of boys and girls.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

- The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. There are no funding resources for this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML