-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(5): 165-172

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140405.01

Cultural Intelligence of English Language Learners within a Mono-Cultural Context

Ebrahim Khodadady 1, Batoul Hasanzadeh Yazdi 2

1Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran

2Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, International Branch, Mashhad, Iran

Correspondence to: Ebrahim Khodadady , Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study explored whether the language institutes where members of a specific community learn English brings about any changes in the structure as well as the relationships found between the factors underlying the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) developed by Ang et al. (2007). To this end, the Persian CQS translated and validated by Khodadady and Ghahari (2011) was administered to 381 Iranians who learned English at advanced levels in several private and semi-private language institutes in Mashhad, Iran. The application of Principal Axis Factoring to the data and rotating the extracted factors via Varimax with Kaiser Normalization showed that the same four factors underlying Iranian university students’ cultural intelligence (CQ), underlie English learners’ CQ as well, i.e., Cognitive, Motivational, Behavioral and Metacognitive. One of the items comprising the Metacognitive dimension of the latter group did not, however, load acceptably on the factor while three items comprising the Behavioral factor cross loaded on the Cognitive factor revealing a lower significant relationship between the two. Unlike a significant and positive relationship found between the Cognitive and Motivational dimensions of university students’ CQ, learning English results in establishing a negative relationship between the two dimensions. The results are discussed and suggestions are made for future research.

Keywords: Cultural intelligence, Language learning, Institutes, Factors

Cite this paper: Ebrahim Khodadady , Batoul Hasanzadeh Yazdi , Cultural Intelligence of English Language Learners within a Mono-Cultural Context, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 165-172. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140405.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

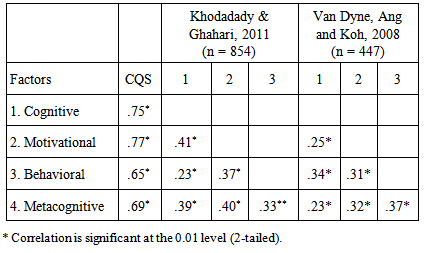

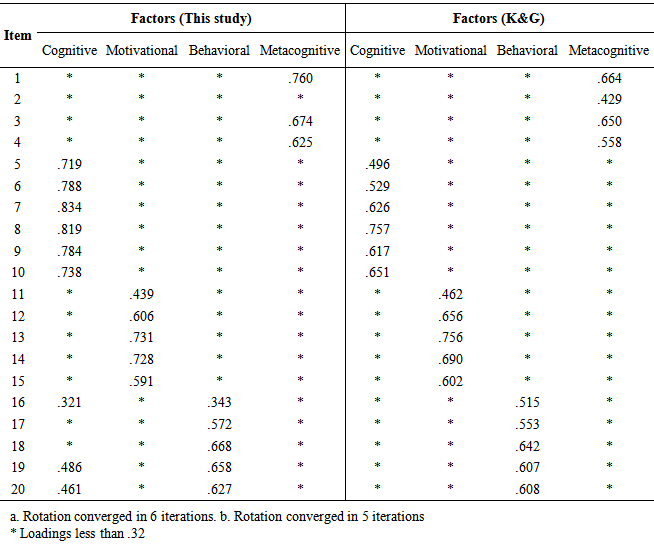

- English has gained the status of an international language and is thus taught in Iran at primary, secondary and higher education centers to achieve a number of objectives. Khodadady, Arian and Hossein Abadi (2013) developed and validated an English Language Policy Inventory (ELPI) which shows that seven objectives are pursued in Iran among which three are closely related to cultural intelligence (CQ), i.e., International Interaction, Internationalizing Native Culture, and International Understanding. These objectives will be achieved if Iranian English learners acquire the CQ defined as their capacity to adapt themselves effectively to situations of cultural diversity (Earley & Ang, 2003). Although acquiring CQ may be facilitated through training in defense departments for specific purposes, the Iranian English learners basically acquire it indirectly through the formal teaching of language in the mono-cultural settings of institutes. According to Baker and Hamilton (2006), for example, the American authorities have considered the cultural training of US personnel fighting the war in Iraq as one of their highest priorities. Resorting to the priority, Imai and Gelfand (2010) argued that cultural understanding will not materialize unless individuals gain the ability to negotiate effectively across cultures. After reviewing the literature on management they announced that “most research compares and contrasts different negotiation behaviors as they occur in mono-cultural contexts across cultures, instead of directly examining intercultural settings where cultural barriers exist right at the negotiation table” (p. 83).Similar to Imai and Gelfand (2010), the 20-statement Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) developed by Ang et al. (2007) and translated into Persian by Khodadady and Ghahari (2011) [henceforth K&G] was employed in this study to find out whether the advanced English language (AEL) learners’ CQ in Iran comprises its four dimensions: meta-cognitive, cognitive, motivational and behavioral. As the first dimension, the meta-cognitive factor specifies an individual’s level of cultural mindfulness during intercultural interactions (Ang & Van Dyne, 2008). It consists of four statements such as “I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I use when interacting with people with different cultural backgrounds”. The Cognitive dimension of CQS, however, consists of six statements dealing with individuals’ familiarity with the similarities and differences found in the norms, practices, and conventions of other cultures (Ang et al., 2006, 2007; Ang, Van Dyne & Koh, 2006; Ang & Van Dyne, 2008). The statement having the highest loading on the cognitive dimension of CQ (.76) in K&G’s study, for example, reads “I know the marriage systems of other cultures”. Similarly, as the third dimension, the Motivational factor of CQS comprises five statements reflecting the individual’s ability “to direct attention and energy toward learning about and functioning in situations characterized by cultural differences” (Ang et al., 2007, p. 338). The statement having the highest loading (.76) on Motivational dimension of university students in K&G’s study, for example, reads “I am sure I can deal with stresses of adjusting to a culture that is new to me”.The last factor underlying the CQS deals with its Behavioral dimension. It consists of five statements describing individuals’ verbal and non-verbal behaviors when they interact with people from other cultures (Ng & Earley, 2006; Thomas, 2006). The highest loading (.64) statement in Khodadady and Ghahari’s (2011) research, for example, reads “I vary the rate of my speaking when a cross-cultural situation requires it”. Studies in Western countries show that Metacognitive factor is extracted as the first followed by Cognitive, Motivational and Behavioral dimensions (Van Dyne, Ang & Koh, 2008). However, K&G’s administration of the Persian Version of CQS to 854 undergraduate and graduate university (UGU) students showed that the Metacognitive dimension is the last as shown in Table 1.

|

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- Four hundred forty four, 310 female (69.8%) and 134 male (30.2%), English language learners at upper intermediate (n=63, 14.2%) and advanced (n=381, 85.8%) levels took part in the present study voluntarily. The responses of 381, i.e., 265 (69.6%) female and 116 (30.4%) male, AEL learners were, however, analyzed in the present study to confine its scope to one specific linguistically homogenous group. Their age ranged between 14 and 51 (mean = 22.43, SD = 6.45). They had registered in the general English classes at Azaran (n = 54, 14.2%), Hafez (n = 16, 4.2%), ILI (n = 48, 12.6%), Jahad (n = 49, 12.9%), Khorasan (n = 65, 17.1%), Kish (n = 21, 5.5%), Momtaz (n = 34, 8.9%), Safir (n = 56, 14.7%), and Shokouh (n = 38, 10.0%) language institutes in 2013.While 191 participants (50.1%) had not specified their level of education, 162 (42.5%), 22 (5.8%) and six (1.6%) were holding bachelor, master and PhD degrees in agriculture (n=5, 1.3%), engineering (n=52, 13.6%), humanities (n=133, 34.9%), medicine (n=17, 4.5%) and sciences (n=89, 23.4%), respectively. In terms of their marital status, 317 (83.2%) of participants were single and the rest had married (n=64, 16.8%). Out of 381, 126 (33.1) had travelled abroad. They had visited Afghanistan, America, Austria, Azerbaijan, Canada, China, Dobie, England, France, Germany, India, Iraq, Italy, Lebanon, Malaysia, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Slovakia, Sweden, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. They had stayed in these countries from one to 15 days (n=86, 22.6%), one to three months (n=29, 7.6%), four months to one year (n=2, .5%) and more than one year (n=9, 2.4%). They were speaking Persian (n=377, 99.0%), Turkish (n=3, .8%) and Arabic (n=1, .3%) as their mother language.

2.2. Instruments

- Three instruments were employed in the study: a Demographic Scale and Cultural Intelligence Scale and Foreign Language Identity Scale (FLIS). To limit the scope of the study, the results related to the FLIS will be reported in a separate paper.

2.2.1. Demographic Scale

- The Persian Demographic Scale (DS) consisted of twelve short answer and multiple choice items dealing with the name of participants’ language institute, their field of study at university, year of study, age, gender, marital status, degree of education, language spoken at home, foreign languages known, travelling abroad, the countries visited and duration of visit.

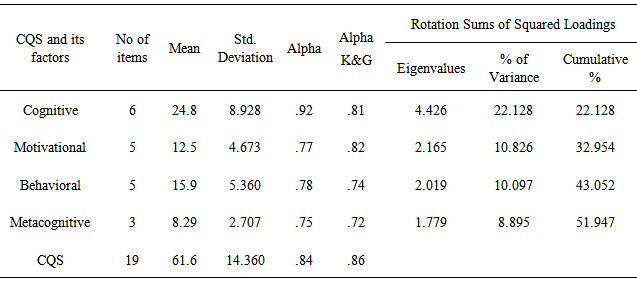

2.2.2. Cultural Intelligence Scale

- The Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) developed by Van Dyne, Ang and Koh (2008) and translated into Persian by K&G was employed in the present study. It consists of 20 statements such as “I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I use when interacting with people with different cultural backgrounds.” The participants were required to completely agree, agree, agree to some extent, offer no idea, disagree to some extent, disagree and completely disagree with the statements. The responses given by 854 UGU students in K&G’s study showed that the CQS is a reliable measure (α = .86) of cultural intelligence as are its four underlying dimensions, i.e., Cognitive (α =.81), Motivational (α =.82), Behavioral (α =.74), and Metacognitive (α =.72).

2.3. Procedure

- Upon having adequate number of copies available, the second researcher contacted the authorities of Azaran, Hafez, ILI, Jahad, Khorasan, Kish, Momtaz, Safir, and Shokouh language institutes in Mashhad and secured their approval to administer the instruments of the study under their EFL teachers’ supervision. On specified dates, she attended the classes in person and distributed the instruments explaining what the participants were required to do. As they were answering the questions, she walked along the aisles drawing their attention to various sections of the scales and emphasizing the importance of their responses. She encouraged them to raise whatever questions they had. Other than a few question related to the demographic section, no particular questions were raised regarding the 20 statements comprising the CQS.

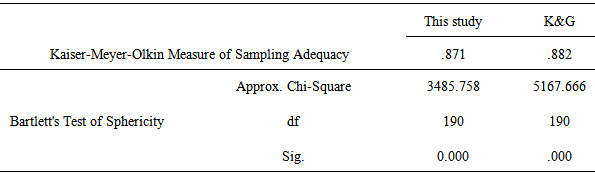

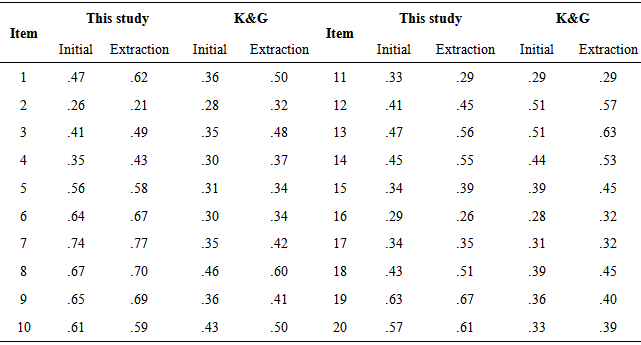

2.4. Data Analysis

- The descriptive statistics of the items comprising the CQS was run to determine how well they had functioned. For the ease of presentation and discussion, the seven points on the scale were reduced to three by collapsing completely agree, agree, and agree to some extent into one, i.e., agree, as were disagree to some extent, disagree and completely disagree to another, i.e., disagree. For estimating the reliability level of the CQS, Cronbach’s alpha was employed. Principal Axis Factoring method was utilized to determine the structure of LVs underlying the cultural intelligence of EFL learners. The initial eigenvalues of one and higher were adopted as the only criterion to determine the number of LVs. The extracted LVs were then rotated via Varimax with Kaiser Normalization to have a clear understanding of what underlies the CQ of these particular learners. Following Tabachnick and Fidell (2001), .32 was adopted as the minimum loading of an item and the loadings less than the minimum were removed. All analyses were conducted via the IBM SPSS Statistics 20 to test the hypotheses below.H1.The 20 items comprising the Persian CQS will load on the same factors extracted by K&G.H2.The four dimensions of CQ in this study will correlate with each other almost in the same magnitude as they did in K&G’s study.

3. Results

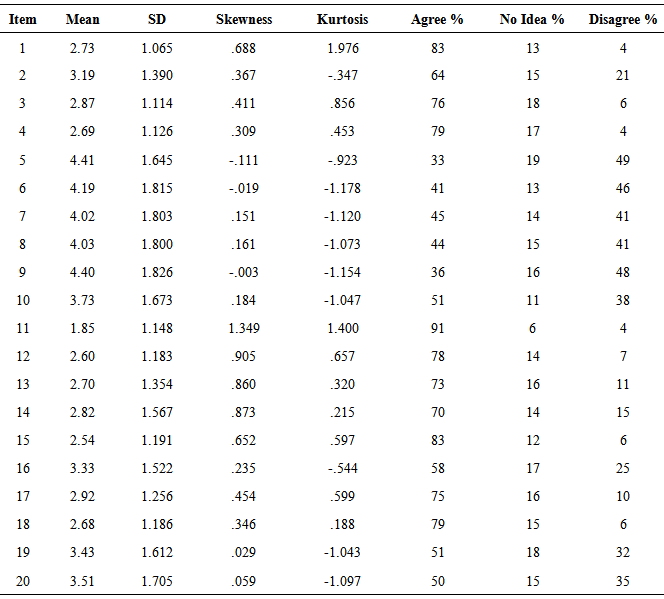

- Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the items on the CQS. As can be seen, the mean of responses given to items ranges from 1.84 (item 11), “I enjoy interacting with people from different cultures”, to 4.41 (item 5), “I know the legal and economic systems of other cultures”. As it can also be seen, these mean scores have been obtained because the highest (91%) and lowest (33%) percentage of the respondents have agreed with items 11 and five, respectively. These results are similar to those of K&G reporting the highest and lowest percentages of agreement on items 11 (80%) and five (29%) though they differ in magnitude.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussions and Conclusions

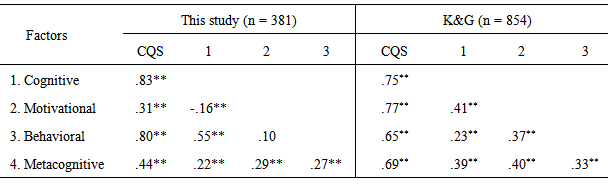

- The 20-statement Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) developed by Van Dyne, Ang and Koh (2008) is a factorially valid measure of cultural intelligence (CQ) for UGU students whose mother language is Persian. However, as a cognitive domain (see Khodadady and Dastgahian, 2013, 2015) its constituting statements or species drops to 19 in the case of AEL learners studying English in language institutes in Mashhad, Iran. In spite of having fewer species, the same four factors, nonetheless, underlie AEL learners’ CQ, i.e., Cognitive, Motivational, Behavioral and Metacognitive. The factors constituting the cultural intelligence though relate to each other differently when UGU students studying various fields of knowledge in their mother language are compared with those who attend language institutes to learn English.The Cognitive dimension of UGU students’ CQ correlates the highest with the Motivational factor, explaining seventeen percent of variance in each other. For English learners, however, the two dimensions relate to each other negatively by sharing only three percent of variance, indicating that the more cognitive the English learners are of their addressees’ culture, the less motivated they become to interact with them. Although the present researchers could not find any study done on the CQ of foreign language learners in other contexts to compare the results of this study with, these findings contradict the coefficients reported by researchers in other countries with participants other than language learners. Imai and Gelfand (2010), for example, recruited 236 full-time employees of multinational companies to fill out the CQS online without specifying what language other than English they spoke. Their reported correlation coefficient for the Cognitive and Motivational dimensions is .42 (p <.01), which is almost the same as the coefficient (r = .41, p <.05) reported by Smith (2012) with 137 university students 41 of whom spoke at least another language in addition to English. These results show that the more knowledge employees and university students gain from other cultures, the more motivated they become to interact with the people of those cultures. Since Khodadady and Ghahari (2012) explored the relationship between CQ and English language proficiency, their findings explain the results of the present study best. They administered the CQS and Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) to 145 Iranian university students majoring in fields ranging from biology to physics offered in Persian as their mother language. Based on their total scores on the TOEFL, they divided the participants to high, middle and low proficiency groups and correlated their scores with the CQS and its four dimensions. Their results showed that the middle proficiency test takers’ scores on the structure subtest of the TOEFL correlated negatively but significantly with the cognitive (r = -.24, p <.05) and motivational (r = -.26, p <.05) dimensions, indicating that only middle proficiency test takers rate their own cognitive and motivational CQ high while their observed structural knowledge of English language is low. In other words, the more structurally proficient they become in their English language, the less they claim to be familiar with English culture lowering their motivation for learning the language. Future research is though needed to find out whether the content-based achievement of the EFL learners show similar relationships with the four dimensions of their CQ. Since neither Cognitive nor Motivational dimensions of high proficiency participants’ CQ in Khodadady and Ghahari’s (2012) study correlated significantly with their performance on the TOEFL and its structure and reading subtests, it can be concluded that they have a more realistic rating of their CQ than their middle proficiency counterparts. This conclusion is supported in this study when the Motivational dimension of the English learners who have travelled abroad (M = 11.75, SD = 4.87) is compared to those who have not visited any country (M = 12.88, SD = 4.56). The independent samples T-Test shows that the Motivational CQ of non-visitors is significantly higher than the visitors (F = -2.33, df = 442, p <.02). The magnitude of the differences in the means, according to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines was very small (eta squared = .01).The findings of this study are also compatible with those of Khodadady and Navari (2012). They developed and validated the Foreign Language Identity Scale (FLIS) 470 female AEL learners in institutes. Based on the six dimensions they extracted from the FLIS, i.e., idealized society, idealized communication, idealized means, idealized opportunities, global connection, and global self-expression, they announced that female Iranians in Mashhad learn English by creating an identity in an idealized society in which they can acquire the means to communicate best and find the opportunity they lack, reveal and improve the personality they possess, get better jobs and connect to the rest of the world. The foreign language identity, however, seems to disappear when the learners go abroad and study at universities (p. 30).The findings of this study show that the Motivational dimension of AEL learners’ cultural intelligence relates adversely to their cognitive dimension when they travel abroad and interact with peoples of other cultures, implying that there are possibly two types of cultural intelligence, empirical and idealized. It remains, however, to be explored whether the CQS holds any significant relationships with the FLIS and what percentage of variance their underlying dimensions explain in each other. The results obtained in this study seem also to support Khodadady, Sarraf, and Mokhtari’s (2013) observation indirectly that the factors underlying the psychological measures such as CQS reveal varying degrees of loading, if not change, as a result of the settings in which the learners study the English language. Instead of choosing their participants from English institutes as Khodadady and Navari (2012) did, Khodadady et al administered the FLIS to 680 grade three senior high school (G3SHS) students who had to study English along with other subjects such as biology and history. Instead of six factors, they extracted five, i.e., Idealized Reception, Idealized Society, First Languaculture, Idealized Self-Expression, and Idealized Communication, indicating that the foreign language identity of those who learn English in private institutes differs from those who study it in public schools as part of their curriculum.Although the same number of factors having almost the same items were extracted from the CQS in this study with AEL learners in institutes as K&G did with UGU students majoring in various fields of study, the three items forming the Behavioral factor, i.e., Item 16, “I change my verbal behavior (e.g., accent, tone) when cross-cultural interaction requires it”, items 19, “I change my non-verbal behavior when a cross-cultural situation requires it” and 20, “I alter my facial expressions when a cross-cultural interaction requires it” cross load acceptably on the cognitive factor (0.32, 0.49 and 0.46, respectively) as well. The very cross loadings of these items on a different factor, has brought about the highest correlation coefficient (r = .55, p<.01) between the Cognitive and Behavioral dimensions of English learners which is noticeably higher than the coefficient reported by K&G (r = .23, p<.01). It is, therefore, suggested that the factorial validity of scales such as the CQS be explored with Principal Axis Factoring with participants recruited from places where a common objective such as language learning is pursued. It is also suggested that the CQ of English learners be investigated in relation to other types of capacities such as emotional, fluid, social, and spiritual intelligences to find out what intelligences bear on language learning most. It is also worth exploring why certain factors such as Cognitive dimension of CQ stay relatively stable in their item structure from samples to samples while other factors such as the Metacognitive aspect of CQ change.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML