-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(4): 157-164

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.06

Chinese International Students’ Value Acculturation while Studying in the United States

1Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, U.S.

2Assistant Professor of Psychology, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, New York, U.S.

Correspondence to: Yimin Fan, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, U.S..

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

International college students often face the challenge of integrating their native cultural values with those of their host country. The purpose of this study was to explore the changes in Chinese international students’ cultural values and identity after experiencing acculturation while studying in the United States by comparing survey results among Chinese international students studying in the U.S., native Chinese students studying in mainland China and European American students studying in the United States. Participants (N = 197) completed surveys measuring traditional Asian values, European American values, and Asian identity. It was hypothesized that Chinese international students’ values and identities would be different than both their European American classmates and their counterparts in China. This might be due to Chinese international students’ values and identities changing after being exposed to European American values on a daily basis. As expected, Chinese international students’ responses on values and identities differed significantly from European American students. However, they did not differ significantly from Chinese students who live and study in mainland China. The findings suggested the firm stability of Chinese international students’ value systems and the difficulty of acculturation for these students. In addition, it helped illustrate the importance of acculturation in their lives. Implications for future research are discussed.

Keywords: Values, Acculturation, Chinese international students, Chinese students

Cite this paper: Yimin Fan, Brien K. Ashdown, Chinese International Students’ Value Acculturation while Studying in the United States, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 157-164. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.06.

Article Outline

1. Chinese International Students Value Acculturation while Studying in the United States

- Asian international students (i.e., international students who were born and raised in Asian countries) presently compose 3.6 percent of the total enrollment of university students in the United States. Nearly 22 percent of Asian international students in the U.S. are from China (Institute for International Education [IIE], 2011). Chinese student enrollment in the U.S. rose to a total of nearly 158,000 students in 2011, making China the leading sending country of international students in the U.S. for the second year in a row (IIE, 2011). These Chinese international students encounter many academic and cultural challenges due to language barriers, differences between individualistic values found in the U.S. and collectivistic values found in China (Sosik & Jung, 2002), and other adjustment factors. Chinese culture puts more emphasis on social community (Durkheim, 1933), group goals and harmony (Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961). Coming from this culture, Chinese international students may be more familiar with collectivistic living and studying environments. In order to adapt to an individualistic society such as that in the U.S., most of them have to make great effort to become proficient in English as well as in other acculturation processes (Ye, 2005). Among the difficulties Chinese international students normally confront during this acculturation process, challenges associated with values are especially important because in order to achieve success in the U.S., the students not only need to understand and successfully navigate the host culture, they also must find a balance between the value systems in both European American culture and their native Chinese culture (Iwanoto & Liu, 2010).Acculturation has long been of interest to social scientists. Early research considered acculturation as a unidimensional process in which a person released aspects of his or her heritage culture while acquiring aspects of a new culture (Gordon, 1964). More recent research indicated that acculturation should be considered a bidimensional process in which a person could preserve his or her cultural heritage while acquiring aspects of the receiving culture (Berry, 1980). For example, Berry, Trimble, and Olmedo (1986) defined acculturation as the changes in cultural behaviors and values that individuals experience as a result of contact between two cultures.Current research considers acculturation as a multidimensional process (e.g., Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006). For instance, behaviors, values and identity are repeatedly proposed as major dimensions or domains of acculturation (Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995; Kim & Abreu, 2001; Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., & Szapocznik, J., 2010). Within this multidimensional approach, some research suggests that value acculturation is more stable than behavioral acculturation (Sodowsky & Carey, 1988; Szapocznik, Rio, Perez-Vidal, Kurtines, Hervis, & Santisteban, 1986) and that people may adopt specific behaviors necessary for culturally accepted success faster than adopting the values of a new culture (Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1980). For example, most foreign women who live in Iran cover their hair in public to show respect for Islamic culture. This behavior of the foreign women does not necessarily indicate that they firmly believe that hair is an extremely private body part (Paidar, 1995). Covering hair is a behavior that most foreign women adopt in Iran, and this behavioral adoption usually occurs before value or religious adaption. Value acculturation may require more efforts than behavioral acculturation because value change will result in the modification of a behavior (Maio & Olson, 1998), but the modification of a behavior does not necessarily result in a change of values (Hirose, 2004). Therefore, in the current study, the operational definition of Chinese international students’ acculturation is the degree to which they adopt mainstream European American values in the United States.Most current research about acculturation focuses on the negative aspect of both the process and the outcomes of acculturation (Schonpflug, 2002), such as acculturative stress, depression, and other coping strategies (Berry, 1994; Kim, 2006; Rosario-Sim & O’Connell, 2009). However, little research considers the positive effects of acculturation, such as valuable multicultural discoveries and more tolerable perspectives. For example, because China has a national policy that allows parents to only have one child, together with the less dominant religious culture of Christianity, Chinese media and people don’t debate about abortion as much as they do in the United States (McCoyd, 2010). Some Chinese international students may feel confused by the social issue of the legitimacy of abortion in the United States when they first encounter it. However, once they begin to understand the situation, they will be able to compare it with related Chinese policies, and therefore gain unique perspectives and insights on the issue. During this process, the students may unconsciously experience acculturation in different ways: some may still consider abortion necessary in certain conditions; others may begin to believe that abortion is morally wrong and fight against it. In either case, students have an opportunity to take a second look at their previously internalized values and then decide if they want to change them. Considering the equal importance of positive and negative acculturative effects on international students (Sue, 1989), the current research aims to examine both positive and negative effects that acculturation may have on Chinese international students’ values.Adolescents and adults experience acculturation in different ways (Sam & Oppedal, 2003). This transition from adolescence to young adulthood, often called emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2004), is a crucial process in people’s lifetimes because this may be the origin or the ultimate motivation for emerging adults to make changes to their worldviews (Arnett, 2004; Pine, Cohen, Johnson, & Brook, 2002). Many Chinese international students come to the U.S. during this period of emerging adulthood for undergraduate and graduate studies (Yan & Berliner, 2011). With the rapid development of Chinese economy in recent years, there is a continuous increase in the population of Chinese international students who pursue undergraduate studies in the United States (2011). Therefore, they are likely to experience the transitional period of emerging adulthood in a culture very different than their own. With this change of environment and culture, many of them may find the acculturation process confusing and difficult to cope with because of the double pressure of growing to be adults and adapting to an individualistic culture (Ye, 2005). During this period of Chinese international students’ acculturation, the students are required to navigate developmental transitions and psychological maturation simultaneously in both academic and personal growth (Sam & Oppedal, 2003).Compared to U.S. students or native Chinese students, Chinese international students have a unique factor that influences their value system – the acculturation experience (Wei et al. 2007). These young adults are put in an unfamiliar cultural context during a crucial time period of their lives. In the meantime, they are away from familiar environments and therefore need to acquire new skills to survive and be successful in the new host culture. The adaptive outcomes of these international students’ acculturating to the values of European American culture while attempting to maintain aspects of their native Chinese culture may lead to the development of a distinctive subculture that is different from both European American culture and the native Chinese culture (Yan & Berliner, 2011). Although Chinese international students may live in and contribute to this subculture, how this subculture influences the students is rarely examined in research. As one of the major aspects of the Chinese international students’ life, their value systems may be influenced by the context of their subculture.The purpose of the present study was to examine whether Chinese international students’ value and identity status have changed after they came to the U.S. We hypothesize that Chinese international students’ values will be more similar to European American cultural values than will the values of native Chinese students. We also hypothesize that Chinese international students’ values will be more similar to native Chinese students than will the values of European American students, thus indicating a set of cultural values for Chinese international students that different from the values of both European American students and native Chinese students. Considering the drastic change of culture that Chinese international students generally experience, we hypothesize that the Chinese international students will be influenced by the European American culture. Such findings will shed light on the acculturation process that Chinese international students’ undergo upon arriving to study in the U.S. as well as provide information about potential solutions for the problems confronted during this stressful cross-cultural transition (Wang & Mallinchrodt, 2006).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- A total of 197 college students (124 men, 73 women) completed questionnaires about their cultural values. The participants were divided into three groups: 95 native Chinese students (55 males) who study at a large university in Mainland China, 48 Chinese international students (31 males) who study at a diverse university in the northwestern United States, and 54 European American students (38 males) who study at the same American university as the Chinese international students. More than 80 percent of our participants ranged in age from 19 to 25 years. Ninety-eight percent of native Chinese students, 65 percent of Chinese international students and 59 percent of European American students ranged in age from 19 to 25 years. As for the academic class standing, 98 percent of the native Chinese students, 65 percent of Chinese international students and 91percent of European American students are undergraduate students. Around 65 percent of Chinese international students in our study came to the U.S. through an international exchange program when they were sophomores at their Chinese university. With the consideration that the same number of international students were still studying as undergraduate students (35% were graduate students) and the growing trend that many Chinese graduate students came to the U.S. after they finished undergraduate studies in China (Wang, 2004), we can conclude that most Chinese international students in this study have spent less than two years studying in the United States.

2.2. Method

- Participants were recruited by using flyers and emails at both the Chinese and U.S. campuses. Participants were asked to complete a group of surveys online with the chance of winning one of two $250 Walmart gift cards. The survey was presented in either Chinese or English: native Chinese students completed the Chinese version of the questionnaire, and all participants living in the United States completed the English version of the questionnaire. All questionnaires were translated from English to Chinese via a rigorous process of back translation (Brislin, 1970). In this process, we first translated all English surveys to Chinese, and then a colleague who is a native Chinese speaker translated the Chinese version of the surveys back to English for us to compare to the original English surveys. Based on the results of the comparison, we further revised the Chinese version of the surveys to make it convey the same message as the original English version of the surveys.Demographics. This section of the questionnaire included items measuring the participants’ gender, age and academic class standing. European American Values Scale for Asian Americans (EAVS-AA). In order to measure participants’ acculturation to European American values, we used this 18-item and multi-linear acculturation scale (Wolfe, Yang, Wong, & Atkinson, 2001). Different items in this measure represent both mainstream Asian values (“Sometimes, it is necessary for the government to stifle individual development”) and European American values (“You can do anything you put your mind to”). Participants responded using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 7 (Strongly Disagree). Higher scores indicate higher tendencies to accept the mainstream value that is contained in each item. This measure was originally designed to assess European American values among Asian Americans; however, because of its utility for assessing European American values, it is being used to measure these values among European American and Chinese students as well. In previous research, the Cronbach’s alpha was .69 and in the current study was .80 across all three samples.Revision of Asian Value Scale (AVS-R). This is a 25-item measure for assessing Asian enculturation (Kim & Sehee, 2004). Enculturation is defined as the process of retaining one’s indigenous cultural values, behaviors, knowledge and identity (Kim, Atkinson, & Umemoto, 2001). The adherence to Asian cultural values is an important dimension of enculturation for Asians who live in the United States (2001). Compared to the EAVS-AA, items on the AVS-R emphasize traditional Asian values (e.g. “One should think about one’s group before oneself”). Participants responded to each statement using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 4 (Strongly Disagree). Higher scores indicate higher tendencies to accept traditional Asian values. In previous research, the Cronbach’s alpha was .86 and in the current study was .72 across all three samples.The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA). This 25-item scale not only measures cultural identity, but also collects participants’ historical background information related to acculturation (Suinn, Ahuna, & Khoo, 1992), such as participants’ preferences on food, languages, music and movies (e.g., “What is your food preference at home?”). Considering none of the three groups of prospective participants in our research were immigrants, three items that only concerned immigrant status (e.g. what generation are you?) were deleted in our modified SL-ASIA (See Appendix A). The items on the SL-ASIA were used as historical and demographic variables in the predictive models described below. The Multi-group Ethnic Identity Measure, Revised (MEIM-R). This 6-item measure is widely used to measure individuals’ ethnic identities (Phinney & Ong, 2007). By using the MEIM-R, we were able to study the differences between Chinese and European American participants’ ethnic identities and their levels of attachment to their native culture. Participants responded to items such as “I have strong sense of belonging to my ethnic group” using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Disagree a lot) to 5 (Agree a lot). Higher scores indicate higher tendencies to accept or form a strong ethnic identity. In previous research, a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 was reported (Phinney & Ong, 2007), and the Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was .91 across all three samples.

3. Results

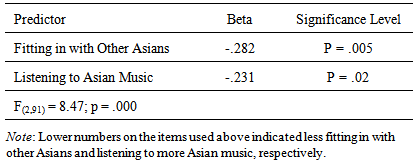

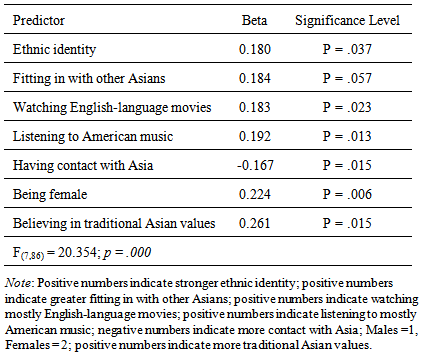

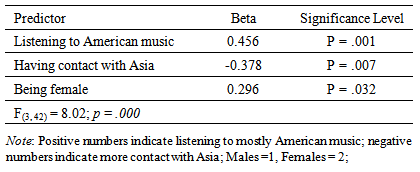

- To test our hypotheses that there would be differences among the groups on cultural values because of the acculturation of Chinese international students studying in the U.S., a series of ANOVAs were computed with the AVSR, EAVS, and MEIM-R, respectively. There was a significant difference between the groups (i.e., European American students, Chinese International students, native Chinese students) on the AVSR (F(2, 194) = 40.60, p = .000). As expected, Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that Chinese international students (M = 3.09; SD = .22) and native Chinese students (M = 3.17; SD = .23) had higher scores on the AVSR than European American students (M = 2.78; SD = .32; p = .000 for both comparisons). This finding suggests that both groups made stronger claims to traditional Asian values than the European American students did. However, the Chinese international students and the native Chinese students did not differ significantly on the AVSR (p = .283). A significant difference was found between the groups on the EAVS (F(2, 194) = 34.99, p = .000). Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that European American students (M = 5.61, SD = .76) scored significantly higher on the EAVS than the Chinese international students (M = 4.64; SD = .55) and the native Chinese students (M = 4.64; SD = .78, p = .000 for both comparisons). However, the Chinese international students and native Chinese students did not differ significantly on the EAVS (p = 1.00). This suggests that European American students made a stronger claim to traditional European American values than the two groups of Chinese students. There was also a significant difference between the groups on the MEIM-R (F(2, 194) = 3.53, p = .031). Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that European American students (M = 3.17, SD = .98) scored significantly lower on the MEIM-R than the Chinese international students (M = 3.71; SD = .74, p = .028). There was no difference between the European American students and the native Chinese students (M = 3.48; SD = 1.18; p = .23), or between the Chinese international students and the native Chinese students (p = .67). When looking at the whole sample, men and women differed only on the MEIM-R (t(195) = -4.16; p = .000). Men (M = 3.24; SD = 1.14) had significantly lower scores than women (M = 3.81; SD = .75), suggesting that women had stronger ethnic identities than men, regardless of their ethnic group.When looking at gender differences within each sample, Chinese men (M = 4.38; SD = .78) and Chinese women (M = 5.00; SD = .63) differed on the EAVS (t(93) = -4.28; p = .000). Chinese men (M = 3.13; SD = 1.34) and Chinese women (M = 3.97; SD = .67) also differed on the MEIM-R (t(93) = -4.00; p = .000). Chinese women had a higher claim to European American values and a stronger ethnic identity than Chinese men. There were no other gender differences. Using items from the SL-ASIA, demographic variables, and scores on the MEIM-R, stepwise regression models were created to determine what variables best predicted scores on the AVSR for all three groups. The significant predictors of AVSR scores in native Chinese students were feeling like they did not fit in with other Asian students (beta = -.282; p = .005) and listening to mostly Asian music (beta = -.231; p = .02). See Table 1 for more information.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- This study examined Chinese international students’ values acculturation by comparing their cultural values to native Chinese students who live and study in China and European American students who live and study in the U.S. As expected, native Chinese students and Chinese international students regard traditional Asian cultural values more highly than European American students, and European American students regard traditional European American values more highly than the two groups of Chinese students. We hypothesized that Chinese international students’ values may be impacted by their daily encounter with the European American culture as their living environment changed. However, based on our survey results, the Chinese international students and native Chinese students’ acceptance of cultural values did not differ significantly on either traditional Asian values or European American values. This suggests that the cultural values of the Chinese international students did not change after being exposed to European American culture. As mentioned by Ardelt, there are two major influences that affect people’s value stability: environment and personality (2000). Because the majority of the Chinese international students who took the survey have been in the United States for less than two years, the environmental influences on values change may not have been long enough or strong enough to affect values change. The correlation between duration of environment change and value change needs to be further explored in future research.Interestingly, our research results showed that female Chinese international students made stronger claims to European American values and had stronger ethnic identities than male Chinese international students. Because of various historical, physical and cultural factors, Asian men have struggled with the stereotypes of being less masculine than white men of the dominant culture in the United States (Chan, 1998). There’s a common stereotype that Asian men are more likely to be effeminate (Espiritu, 1997). Asian men’s unidimensional, asexual roles in social media (e.g. computer nerds, successful doctors) demonstrate this stereotype (Chan, 2000). On the other hand, Asian men have also been portrayed as hyper-masculine in martial arts master roles such as Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan (Espiritu, 1997). The American society’s conflicting view of Asian men may have a negative impact on their gender identity formation. Another major challenge for male Asian international students in the U.S. is that they may hold different identifications of masculinity from their home culture. For example, typical traits of masculinity in Chinese culture are self-control, collectivism and family recognition through behavioral achievements; whereas masculine traits in America are typically aggressive, independent and competitive (Liu & Chang, 2007). The conflict between these two different sets of values in masculinity in young Chinese international male students’ daily life may cause them stress and thus they become resistant to invest time and energy in acculturation. This resistance may further deepen the American societal stereotype of Asian men and overlook their perspective on masculinity.Although Asian women face the same discrimination as their male peers in many other aspects, they do not have to fight for recognition of their masculinity. Past research has suggested that this problem of Asian men who live in the U.S. is becoming a major obstacle in their process of successful acculturation (Liu, 2002). Compared to their female peers, male Chinese international students in the current study had a weaker sense of Chinese ethical identity and made a weaker claim to European American values. This may indicate that issues associated with their gender led the male Chinese international students to acculturate less successfully than the female Chinese international students. Internalized racial attitudes, conflicts between perceived masculinity and own gender identity, low self-esteem, highly competitive environment are all possible factors that prevent male Chinese international students from developing mature ethnic identities and value systems (Levant & Fischer, 1998; Sue, 1989).Notably, although Chinese international students and native Chinese students did not statistically differ on their values systems, if we examine the results of the two groups’ survey responses, Chinese international students’ responses to many of the survey questions showed a slightly stronger claim to European values than local Chinese students. Because this difference was not statistically significant, any attempt to interpret these findings must be taken very cautiously. For example, only 48 percent of the native Chinese students agreed (including the responses “mildly agree,” “moderately agree” and “strongly agree”) with the statement that “abortion should be legal if the mother’s health is in danger,” but 77% of the Chinese international students chose the same answers. This finding may suggest that the Chinese international student participants of this study are in the beginning stages of the acculturation process. Although their overall value systems did not statistically differ from their peers who live in China, they seem to be slightly influenced by the European American values they experience in the United States. It may be more efficient for future related research to choose participants who have already studied in the United States for more than three years as survey participants to further examine the acculturation process. Or, alternatively, examining changes in values among Chinese international students with a longitudinal design might provide much more insight on this particular issue.According to the participants’ responses to the MIEM-R, Chinese international students made stronger claims to their own ethnic identities than the American students. This finding is consistent with a previous study that explored the resistance of assimilation and acculturation in six Asian international doctoral students (Sato & Hodge, 2009). They proposed that for some Asian international students, when they recognized that it is possible to maintain their own ethnic identities and be successful in the mainstream American culture, the students were able to distinguish their own identities from the influences of the dominant culture in which they were now living (Spurling, 2006). Students who are able to resist cultural assimilation in a new country may have a stronger sense of identity, and the process of resistance of assimilation may in return contribute to their strong sense of identity. Perhaps some of the Chinese international students we surveyed were not only resistant to cultural assimilation, but also strengthened their ethnic identities as a defense against this assimilation.Some of the Chinese international student participants seemed to embrace more European American values than the native Chinese participants, although the results did not reach statistical significance. Considering the results of previous studies (e.g. Sato & Hodge, 2009; Spurling, 2006), there appears to be two different approaches to acculturation among Chinese international students. With the first approach, Chinese international students may be open to accept and practice traditional European American values and/or pursue acculturation. With the second approach, Chinese international students may deliberately maintain the cultural identity that is consistent with their country of origin and not pursue acculturation of European American values. It may be interesting for future research to focus on the background differences (e.g. personality, childhood environment, age, etc.) between these two different attitudes of Chinese international students and examine more closely the effects of ethnic identity on acculturation processes.Some limitations of this study should be noted. Due to limited resources, we recruited both undergraduate and graduate Chinese international students, and mixed their responses in one sample group. It is important to note that the Chinese international students of different ages may be influenced by European American values differently. Chinese students of different academic class standing and length of time in the U.S. may also experience the acculturation process differently. Another notable limitation of our study was that we did not examine individual difference variables, such as personality or intelligence. For newcomers to the United States, these individual difference variables may have a stronger influence on their values change than their interaction with the host culture.Overall, this study provides some insight into the values system of Chinese international students in the United States. Although the values of Chinese international students did not differ statistically from native Chinese students, there were observable differences between the survey results of these two groups. This finding points to the possibility that more significant values and identity modification among Chinese international students may occur after a longer period of time living in the U.S. More research is needed to investigate the predictors and consequences of Chinese international students’ attitudes on value and identity status when facing acculturation. The present study and other related studies will contribute to the promotion of Chinese international students’ academic and social success in the United States as well as the improvement of the cross-cultural communication.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML