-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(4): 146-156

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.05

Acting or Hesitating? Long-Term Relations between Parents’ Action Orientation and the Child’s Later Shyness and Sociability in Adulthood

Georg Stoeckli

Institute of Education, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Correspondence to: Georg Stoeckli, Institute of Education, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study aimed to find long-term relations between action orientation (the ability to act efficiently and to reach goals even under adverse conditions) in mothers and fathers, measured when the child was 8 years old, and the adult child’s active coping, shyness, and sociability, measured 22 years later. The hypothesis was that active coping serves as a mediator between parents’ action orientation and the child’s shyness in adulthood. Participants were 134 mother-child and 116 father-child dyads in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. All questionnaires were sent and returned by mail. Separate structural equation models for mothers and fathers confirmed the expected mediating effect of active coping within both samples. In addition, action orientation in mothers (not in fathers) was positively associated with the child’s sociability in adulthood. No gender differences between sons and daughters emerged. The findings of this study support the notion that action orientation is a useful parameter that should be systematically adopted in future research on socialization processes.

Keywords: Longitudinal Study, Action Orientation, Parenting, Shyness, Sociability

Cite this paper: Georg Stoeckli, Acting or Hesitating? Long-Term Relations between Parents’ Action Orientation and the Child’s Later Shyness and Sociability in Adulthood, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 146-156. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- I know I should tackle things more efficiently. In critical situations I usually hesitate too much, and I brood over things repeatedly. I always see a lot of alternatives and options, and I get mired in them. Even when I finally come to a decision, I’m not sure whether I will actually carry it out.Let us suppose that the above statement was made by a parent of an 8-year-old. From the perspective of action control theory [59, 60], this mother or father’s problem is a lack of action orientation. Action-oriented parents would express the sheer opposite of the above statement. They would make decisions right away and tackle problems quickly, because they manage to have control over intrusive and distracting cognitions or alternative plans [59]. This study conceived parental action orientation as an important functional element in the parent-child relationship. The aim was to find long-term relations between action orientation in mothers and fathers, measured when the child was 8 years old, and the adult child’s active coping, shyness, and sociability, measured when the child was 30 years old. It was hypothesized that active coping mediates the link between parents’ action orientation and the child’s shyness in adulthood. An extensive body of research indicates that parenting affects children’s development of social skills and social impairments such as shyness, social withdrawal, low sociability, or reticence [9, 19, 41, 42, 87, 94]. However, empirical evidence on long-ranging connections between maternal and paternal behavioral characteristics and the child’s later shyness in adulthood is very sparse [42]. In particular, there has not been any research exploring the predictive value of parental action orientation for a child’s later coping and social outcomes.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Action Orientation

- The concept of action orientation was developed as part of a broader theory of volitional action control [60]. Action orientation refers to a personality disposition that facilitates the fulfillment of action plans and the achievement of goals, even under adverse conditions and in view of competing alternatives [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 62]. Individuals characterized as action-oriented are able to adjust to demanding situations quickly, because they apply their cognitive and motivational resources fully to a current task. They may become even more efficient under difficult and challenging conditions [59]. Thus, action orientation is regarded as a change-promoting mode of control that enables goal-oriented and consistent regulation of actions [55]. In contrast, individuals with a very low or with a lack of action orientation, in Kuhl’s theory characterized as state-oriented, deplete their cognitive and motivational resources because they ruminate on all kinds of alternatives, earlier experiences in comparable situations, or all imaginable consequences of a certain action in the future. Hence, instead of taking action and moving forward, state-oriented individuals tend to hesitate and to brood over eventualities. In other words, the absence of action orientation is understood as a change-preventing mode that inhibits appropriate action control [59, 60]. A number of studies have demonstrated the benefit of action orientation in diverse domains such as making decisions, initiating intended actions, and performing cognitive tasks [54]. Experimental studies revealed that action orientation is connected with performance either directly or as a mediator/moderator [29, 39, 49, 54, 100, 102]. According to McElroy and Dowd [72], low action-oriented or state-oriented individuals do not adequately adjust their emotions to the given circumstances. The more flexible adjustment of affect and coping in high action-oriented individuals seems especially beneficial following failures. Because action-oriented individuals are far less preoccupied with failures, they outperform others in challenging situations [27]. The distinction between high and low action orientation described above allows the supposition that high actionoriented parents probably exhibit more active, goal-oriented, and straightforward parenting behaviors that affect the child’s coping abilities (and subsequently the child’s shyness) in a more positive direction than the presumably rather indecisive and hesitating behaviors exhibited by low action-oriented parents. This means that action-oriented parents may first and foremost help the child to develop effective coping skills through behavioral modeling or intervention and support. I will outline this idea in the section after next.

2.2. Shyness and Sociability

- In the context of this study it is particularly important to consider the action-related aspects of shyness and sociability. Shyness is defined as wariness, discomfort, and tension in the presence of others and the inhibition of normally expected social behavior [16, 22, 24, 46, 104] or as a combination of social anxiety and behavioral inhibition [5, 31, 66, 68, 96]. Thus, the inhibition of behavior is a typical attribute of shyness. Shy people have difficulty selecting and executing appropriate and straightforward actions in social situations [24]. From a motivational point of view, shyness can be characterized as a conflict between two simultaneous contradictory tendencies: the motivation to approach others and the tendency to avoid social contact because of unfamiliarity or social anxiety [2, 3]. The resulting approach-avoidance conflict makes it difficult for shy persons to deliberately pursue social goals. Another reason for the behavioral problems of shy people is their anxious preoccupation and significantly heightened self-focused attention during demanding social situations [74]. Self-focusing deducts cognitive capacity from ongoing interactions and makes it difficult to direct attention to the situation, intended actions, or other people [31]. Furthermore, low social self-efficacy (subjective incapability to act appropriately in social situations) seems to be an important handicap of shy adults [44]. All of these characteristics affect a shy person’s ability to focus or shift attention as needed and to activate or inhibit behavior as needed, which are essential factors for the development and the consequences of shyness [4, 5]. In contrast to shyness, sociability (or gregariousness, [40]) is seen as a one-dimensional construct that describes a person’s purposeful preference for affiliation, or the need to approach others and to be with others [16, 46, 67]. Several studies have demonstrated that shyness (social-evaluative concern, inhibition, and low self-regulation) and sociability (a social approach motive) form two conceptually and empirically separable (but not consistently unrelated) dimensions of social behavior regulation [11, 12, 13, 16, 25, 31, 46, 76]. Low sociability, or the absence of the need to affiliate, is non-conflictual and unrelated to negative emotionality [16, 31]. This is because low sociable individuals may appreciate being on their own, but they do not feel discomfort or concern when they are with others, because they possess the necessary social skills to interact with others successfully [3, 31]. It should be noted, however, that low sociability, which implies no more than the absence of the need to approach others, is not necessarily equivalent to a preference to be alone [3], social disinterest [20, 23, 67], or a preference for solitude [21]. These constructs have been explored extensively in recent research [21, 23], but they are not the subject of this study, which concentrates solely on shyness and sociability. Overall, the action-related implications of sociability are completely different from shyness. Increasing sociability suggests an increasing tendency to initiate actions to be with other people (actions that follow the need to affiliate), whereas increasing shyness more and more inhibits such actions.

2.3. Shyness and Coping

- Those who have suffered from shyness know that that feeling increases in direct proportion to the time which elapses, and that resolution decreases in an inverse ratio; that is to say, the longer the sensation lasts, the more unconquerable it becomes, and the less decision there is left. [98].What Tolstoy describes so accurately in the above passage is a desperately shy person’s complete loss of action control and almost unbearable inability to actively cope with a distressful situation. Indeed, under certain conditions, shy individuals seem to become so over-aroused that they are incapable of coping overtly with the afflicting situation by planning and executing appropriate behavior [32]. Obviously, shyness leads to a restriction of behavioral plans [66]. As a consequence, coping in shy people is largely characterized by doing nothing or by avoidance [31, 32] or by internalizing coping strategies [35, 51 69]. Thus, shy individuals seem to rely on passive or avoidant and rather ineffective behavioral strategies in the face of social stressors. These coping strategies increase rather than reduce the negative consequences of shyness. In fact, previous research suggests that certain coping strategies are associated with specific socio-emotional outcomes. A meta-analysis by Clarke [17] revealed that active coping (cognitive and behavioral strategies and goals aimed at achieving personal control over stressors and emotions) is positively correlated with enhanced social competence and negatively correlated with internalizing difficulties in children and adolescents. An earlier meta-analysis by Penley, Tomaka, and Wiebe [81] including adult samples (age 18 and older) demonstrated that problem-focused coping (seeking information, planning, taking action) was positively correlated with overall health outcomes. In contrast to active or problem-solving coping, internalizing coping (the accumulation of negative internal responses such as crying, worrying, self-blaming) is particularly ineffective and substantially correlated with anxiety [15]. Several recent studies examined the potential role of coping strategies as mediators between shyness and socio-emotional adjustment. A study by Findlay et al. [35] found that the link between shyness and adverse social functioning in children was significantly mediated by internalizing coping. That is, shy children who extensively adopted internalizing coping strategies experienced more loneliness, social anxiety, and negative affect. Kingsbury et al. [51] recently detected a rather complex indirect relation between shyness and social satisfaction; problem-solving coping in boys (not in girls) moderated the path from internalizing coping to social satisfaction. Internalizing coping (a mediator between shyness and social satisfaction) was more negatively associated with social satisfaction in boys who reported lower levels of problem-solving coping. All in all, research on shyness and coping demonstrates the functional relevance of coping strategies for social and emotional adjustment. Internalizing and avoidant strategies are associated with negative outcomes, and active or problem-solving coping corresponds to more positive social functioning. Due to the fact that shyness is associated with passive or avoidant coping behaviors, it may be extremely difficult for a shy person to adopt active or nonavoidant coping, because this requires replacing a given and repeatedly adopted tendency (passivity, avoidance) with an antipodal and unpracticed behavior. Growing self-control may more and more help a person to initiate and sustain the adaptation to more active coping behavior [28]. Not only self-control but also the kind of self-theories (fixed versus malleable personal attributes) may moderate the link between shyness and coping [69]. Accordingly, coping is by no means directly and unalterably fixed upon temperamental or personality preconditions. Moreover, the link between personality and coping is only small to moderate (for a review, see [18]). Hence, there will be other conditions that determine coping behavior beyond temperamental or personality factors. Parenting might be one of these conditions. For example, when action-oriented parents guide their shy child socially or expose the child to social situations that usually elicit fear and withdrawal, they may increase the child’s opportunities to learn how to cope with these stressful situations. In this way, active parenting may influence the course of shyness or social anxiety across development through supporting coping abilities and self-regulation [26, 36, 37]. According to studies by Bhavnagri and Parke [6] and Park, Belsky, Putman, and Crnic [77], active parenting probably affects the child’s social functioning especially during the preschool years. Bhavnagri and Parke [6] reported that mainly the younger preschool children in the sample were rated as socially more competent when parents actively helped their child to play with an unfamiliar peer as compared to a situation where parents remained passive. With a sample of boys, Park et al. [77] demonstrated that children were less inhibited at age 3 when parents rather intrusively asserted their own social goals and behavioral standards over those of the child at this age and earlier. Thus, these studies reveal that taking action by parents to guide the young child’s social encounters is associated with less inhibition and higher social competence in the child. In these cases, the child’s increasing ability to cope with given social situations may serve as a mediator between parenting and the further development of shyness (mediation hypothesis). Thereby, the mediation hypothesis calls into question not only the direction of influences between shyness and coping (shyness à coping, versus coping à shyness) but also the variability and modifiability of shyness. Even if we view the genetic, biological, or temperamental foundations of shyness as stable over time [86, 90], we should nevertheless acknowledge that the actual manifestation and development of shyness is vulnerable to change due to social environmental (e.g., parenting, child care) or personal (e.g., self-control or coping abilities) factors [5, 26, 47, 48, 86].

2.4. Hypotheses

- Following the above statements, I hypothesized in this study that higher action-orientation in mothers and fathers (when the child was 8 years old) would correspond to increased active coping in their adult sons and daughters, and active coping was expected to correspond to lower shyness. Relatively little is known about the role of a child’s coping strategies as a mediator between parenting and the child’s shyness. In this regard, a study by Caples and Barrera [14] is especially informative, as it found that avoidant coping (together with conflict frequency and perceived maternal support) fully mediated the effect of degrading parenting on internalizing symptoms (depression, anxiety) in adolescents.A direct positive effect (rather than mediation) was postulated regarding the path between action orientation and sociability. In contrast, no significant association was anticipated between active coping and sociability (the need to approach others). There is empirical evidence for this assumption. Eisenberg et al. [31] found no significant correlations between constructive coping (active coping, planning, suppression of competing activities, and positive reinterpretation) and (low) sociability. And Causey and Dubow [15] demonstrated that self-reported social competence (that is, the competence to approach others) is unrelated to a variety of coping measures (seeking social support, problem solving, distancing, internalizing, and externalizing).Compared to the virtual neglect of fathers in earlier decades of parenting research [64, 78], there has been a substantial increase in consideration of the role of fathers in the socialization of children [65]. Nevertheless, compared to mothers, fathers still receive less attention in contemporary research [83]. Because the omission of fathers holds for shyness research in particular [42], we have only limited information regarding the role of fathers in the development of shyness, sociability, or coping in children. To minimize this gap, this study included samples of mothers and fathers. However, like other recent studies on parenting conducted with rather small samples [70, 85], the expected relations were tested in separate models for mothers and fathers. Because the very limited number of studies on fathering and shyness in children suggest that children’s shyness is connected to both fathers’ and mothers’ parenting in very similar ways [42, 88], no significantly different findings for mothers and fathers were anticipated. Because of possible gender-specific effects (e.g., [51]), the invariance of the models across sex of child was tested.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

- The original sample of the first inquiry (Time 1, conducted when the child was 8 years old) consisted of 201 mothers and 179 fathers from different regions in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. Participants in the follow-up (Time 2) conducted 22 years later were 134 mothers and their adult child (72 daughters, 62 sons) and 116 fathers and their adult child (55 daughters, 61 sons). The 134 mothers in the final sample represent 67% of the mothers who took part in the first inquiry. The 116 fathers represent 65% of the initial father-child sample. Mothers and fathers who dropped out at the follow-up 22 years later and those who participated in the follow-up did not differ significantly in relevant features like education, educational aspirations for the child (desired schooling), and action orientation. At the time of the follow-up, the average age of the mothers was 58.7 years (SD = 4.1 years), and the age of the fathers was 60.6 years (SD = 3.9 years); sons and daughters were 30 years old (M = 30.1, SD = .26 years). In the mother-child sample 130 of 134 adult children did not live with their parents, 25% were married (father-child sample: not living with parents: 112 of 116, married: 19%). At the time of the first data collection, the participating fathers had an above-average educational level (39% reported having higher education up to university level, in contrast to 25% as per the official Swiss Education and Training Statistics ETS), whereas higher education in mothers (10%) matched the ETS at that time (10.7%). Sons who took part in the follow-up (Time 2) also had above-average educational attainment: Forty-nine percent of the sons and 31.2% of the daughters reported having higher education (concurrent ETS for the population of 25- to 34-year-olds in Switzerland: 31% and 30%, respectively).

3.2. Procedures

- The first data collection (including only mothers and fathers) was conducted after the child had completed first grade (Time 1). The inquiry was part of a study on parents’ experiences with the child’s first year in school [95]. The addresses of eligible parents were made available by the municipal authorities. The questionnaires were sent and returned by mail. The questionnaire for the follow-up study (including mothers, fathers, and the adult child) was mailed in the year that the sons and daughters reached age 30 (Time 2). To allow the inclusion of the adult child in the study, parents were asked to provide the child’s address after clarifying his or her willingness and consent to participate. Action orientation in mothers and fathers. To obtain a general estimate of self-reported action orientation in mothers and fathers, six items following Kuhl’s theoretical construct [56, 57] were developed and integrated in the questionnaire from the first inquiry (Time 1). (In a personal communication, J. Kuhl acknowledged the construct appropriateness of these items.) Four of the six items turned out to build a single factor in the sample of mothers and in the sample of fathers (sample item: “I let nothing put me off my decisions, and I deal with things right away”, response scale from 1 completely wrong to 5 completely right). Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable: mothers .67; fathers .71. Active coping in sons and daughters. Self-reported active coping in sons and daughters was assessed at Time 2 using the three highest loading items of the five-item Offensive Problem-Solving subscale of the Work-Related Behavior and Experience Patterns (AVEM) (Arbeitsbezogene Verhaltens- und Erlebensmuster) [50, 89]. The items were: (1) “If I don’t succeed in something, I say to myself, ‘Now more than ever!’” (2) “A failure doesn’t knock me over but instead makes me try harder,” and (3) “If I’m not able to accomplish something, I persist stubbornly and make an extra effort.” Participants were asked to indicate on a 6-point Likert scale how well each item describes themselves (from not at all to completely). Schaarschmidt and Fischer [89] reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .82 for the subscale. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .84 in both samples.Self-reported shyness and sociability in the adult sons and daughters. Shyness and sociability were measured at Time 2 with a German translation of the Cheek and Buss [16] shyness (nine items) and sociability (five items) scale. Sons and daughters answered on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (entirely true). Sample shyness items are: “I feel inhibited in social situations”; “I feel tense when I’m with people I don’t know well.” Sample sociability items are: “I find people more stimulating than anything else”; “I welcome the opportunity to mix socially with people.” Cheek and Buss [16] reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .79 for the shyness items and an alpha of .70 for the sociability items. The Cronbach’s alphas in this study were: shyness .83 (mother-child sample) and .78 (father-child sample); sociability .69 and .71, respectively.

4. Results

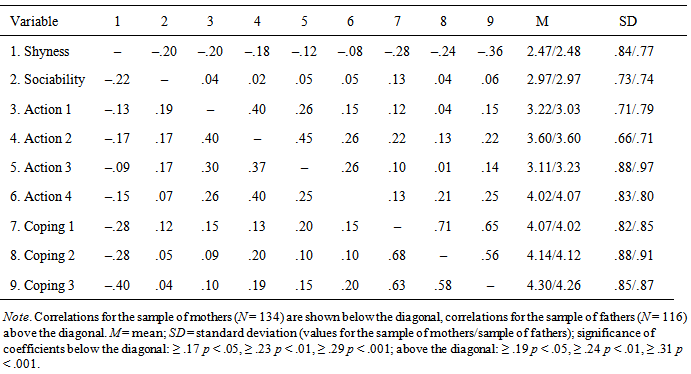

- All calculations were done with AMOS 18.0 [1] using maximum likelihood estimation. The very few missing values were completed by the mean of the remaining items. Since the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the comparative fit index (CFI) are among the least sensitive indexes to sample size [34], these two values were chosen to evaluate goodness of fit in addition to the χ2 value. The construction of the two separate models for mother-child and father-child dyads followed two considerations: All items and indicator variables must be identical in the mother-child and the father-child sample, and in the case of relatively small sample sizes, parsimonious models are recommended [52]. According to Bentler and Chou [8], the ratio of sample size to number of free parameters should be 5:1. In view of these requirements, shyness and sociability were introduced in the models as manifest variables rather than as latent constructs. In contrast, I employed the items measuring action orientation (“action 1” to “action 4” in Table 1) and coping (“coping 1” to coping 3” in Table 1) as indicators of latent constructs. In the measurement models for mother-child and father-child dyads the all factor loadings of the indicator variables were highly significant (all p < .001). Because replacing non-directed arcs with directed arcs does not alter the model fit, the fit indices reported below were achieved in the measurement models as well.

|

4.1. Mother-Child and Father-Child Path Models

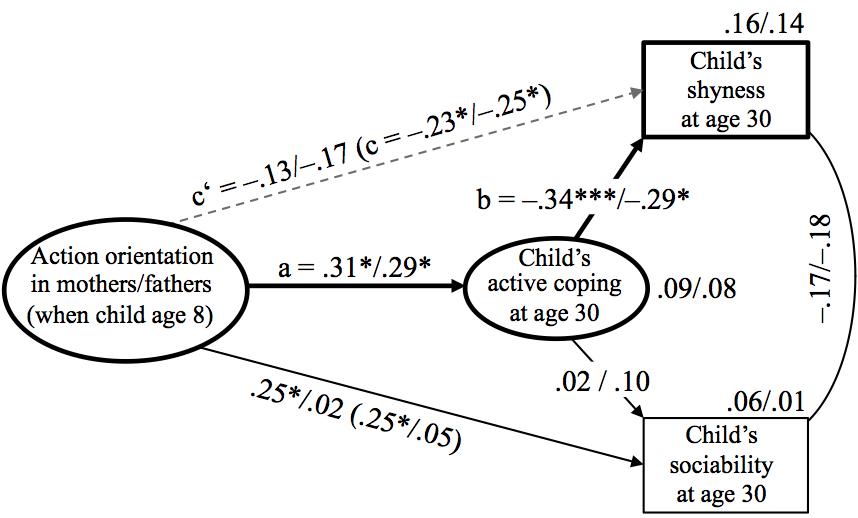

- In the two path models, parental action orientation was treated as an exogenous latent construct (no directed arc ending on it), and shyness and sociability were conceived as dependent variables receiving directed paths from action orientation and coping. There were no negative error variances or out-of-range covariances (standardized estimates > 1) found in the models, and the assessment of skewness and kurtosis (multivariate critical ratio: 1.67 and 1.53, respectively) revealed no violation of the normality assumption. The maximum likelihood test of both models resulted in an excellent overall fit, mother-child: χ2 = 20.01, df = 23, p = .64, χ2/df = .87, CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .000–.060); father-child: χ2 = 20.44, df = 23, p = .62, χ2/df = .89, CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .000–.067). Figure 1 shows path coefficients (standardized regression weights) for mothers/fathers. As expected, there was a positive direct effect between Time 1 action orientation in parents and active coping in children measured 22 years later (sample of mothers/fathers: .31/.29, p < .05) and a negative direct effect between coping and shyness in children (–.34/–.29, p < .05) in both samples. Also as expected, no significant paths from parental action orientation to the children’s later shyness resulted (–.13/–.17, ns), and likewise, the paths from coping to sociability were non-significant. However, the hypothesized positive association between Time 1 action orientation in parents and Time 2 sociability in children could be verified only in the mother-child sample (.25, p < .05) and not in the father-child sample (.02, ns).

4.2. Testing Mediation

- The mediational function of active coping was tested in two ways: (a) following Holmbeck [45] and Baron and Kenny [7], and (b) by estimating the significance of the indirect effects via bootstrap samples. (a) The initial direct effect of parental action orientation (Time 1) on later shyness in sons and daughters (Time 2) was assessed in separate models that did not include the mediator (active coping). The initial path (c in Figure 1) reached significance in both cases (mother-child sample: –.23, p < .05; father-child sample: –.25, p < .05). In contrast, the coefficients of the paths from mothers’ and fathers’ action orientation to children’s later sociability remained stable in the reduced models (coefficients in parentheses in Figure 1). Complete mediation is indicated when the mediated direct path from action orientation to shyness no longer contributes substantially to the model fit [7, 45]. To test this requirement, the regression weight in the mother-child (–.13) and father-child full model (–.17) was constrained to zero. In case of a full mediation, the difference between the freely calculated model and the model with the constrained regression weight should be insignificant. This was the case in both samples, indicating that the path from action orientation to shyness is irrelevant, mother-child: Δ χ2 = 1.53, Δ df = 1, p = .22; father-child: Δ χ2 = 2.23, Δ df = 1, p = .14. (b) In a final step, the significance of the indirect effect from parental action orientation to children’s later shyness was tested based on 2000 bootstrap samples. The indirect effect reached statistical significance in both samples, mother-child: –.11, p < .01, bias corrected 95% CI: lower: –.22, upper: –.03; father-child: –.08, p < .01, bias corrected 95% CI: lower: –.21, upper: –.02. The calculations thus revealed the expected mediation in both samples.

4.3. Invariance across Sex of Child

- The invariance of the mother-child and the father-child model across sex was ensured in three steps. First, the model fit was calculated separately for sons and daughters. These tests confirmed a good fit. In a second step, all factor loadings of the combined baseline models were constrained to be equal across sex. These constrained models did not differ significantly from the unrestricted models, indicating that the factor loadings were invariant across sex. In the third step, the invariance of the regression weights of the paths was evaluated. Again, the invariance was confirmed, suggesting that the relationships among the latent variables in the models were not significantly different for sons and daughters, mother-child: Δ χ2 = 3.03, Δ df = 5, p = .69; father-child: Δ χ2 = 2.27, Δ df = 5, p = .81.

5. Discussion

- This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, the results confirm a long-term correspondence between action orientation in mothers and fathers, measured when the child was 8 years old, and child outcomes, measured when the child was 30 years of age. This finding is noteworthy, because action orientation has not been studied in connection with parenting and child outcomes up to now. Second, the mediation effect confirms an indirect relation between mothers’ and fathers’ action orientation and the child’s later shyness. To date, only a limited number of studies report comparable long-term relations between parenting and shyness in children [5, 42]. The confirmed mediation supports the idea that parental action orientation first and foremost enhances the child’s ability to successfully execute a coping style that is effective as a protective factor against shyness. This result corresponds to earlier studies on parenting as a possible contributor to the child’s coping and self-regulation abilities and the subsequent variability of shyness and behavioral inhibition [26, 36, 37, 77]. Third, the study uncovers similarities (shyness) and differences (sociability) in the functional relevance of mothering and fathering. Because the mediation effect emerged in the mother-child and the father-child sample, no differences in the functional relevance of maternal and paternal action orientation regarding the child’s later active coping and shyness seem to exist. The similarity between findings in mothers and fathers corresponds to the few studies on parenting and shyness in children that include both parents [42, 88]. Similar effects of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting were also demonstrated with regard to the child’s social competence [6, 70]. Thus, in terms of certain social outcomes, mothers and fathers seem to be more or less equally important facilitators.However, it should also be mentioned that previous studies that included both parents simultaneously also found significant differences in the functional relevance of mothers and fathers, for instance with regard to the child’s internalizing problems [73, 43], social initiative, and social competence [71, 97], or the adult child’s empathic concern [53]. In the case of social initiative, social competence, and empathic concern, characteristics of fathers were even more effective than characteristics of mothers [53, 71, 97]. This study revealed differing parenting effects in mothers and fathers as well. Contrary to expectations, the anticipated positive relation between parental action orientation and the child’s sociability appeared only in the mother-child sample. It seems very likely that mothers’ action orientation involves additional attributes and functions that have a positive effect on the child’s sociability and that are probably absent in the father-child relationship. Considering the time point at which action orientation in parents was measured, a long period of possible influences on the child’s social development during childhood and adolescence and the child’s peer relations comes into view. It is well known that the influence of parents on their children’s peer relations continues at least throughout adolescence [10, 33, 75, 101]. During this important developmental period, mothers are more involved in and know more about the child’s social relations than fathers do [99]. Moreover, compared to fathers, child-directed emotional expressiveness and warmth is considerably more pronounced in mothers [82]. Hence, the more intimate relationship with mothers might generate the given association between maternal action orientation and the child’s sociability. Regarding action orientation as an enduring trait-like characteristic, the period of possible influences on the child’s sociability even expands into the early developmental period. In fact, these early years, which the child frequently spends in close contact to the mother, are of great importance for the development of the child’s self-regulation and agency [38, 63]. This study did not address the exact interactional mechanisms that constitute the relation between parental action orientation and the child’s active coping. It will be a task of future research to collect data on child-directed behaviors of high and low action-oriented parents. In the introduction above I speculated that action-oriented parents might help the child to develop coping skills through behavioral modeling or intervention and support. Implications from theory and research on parenting demonstrate that parents have multiple ways of influencing the child’s social functioning and social acceptance outside the family. In a tripartite model that aims to explain the link between the family and the child’s peer relations, Parke and colleagues [79, 80] suggest three modes of parental influence: the quality of parent-child interactions, direct instructions concerning social relationships, and the provision of opportunities for social contact (for an empirical examination of the model, see [70]). It would be very informative to unravel the kind of associations between action orientation and the three modes of influence. For instance, it would be constitutive to know whether high action orientation (a change-promoting mode of control) is actually associated with positive interactions, straightforward and autonomy-oriented instructions, and a higher quality and frequency of social opportunities, whereas low or absent action orientation (a change-preventing mode of control) possibly corresponds to less optimal interactions, dependency-oriented instructions, and the constraint of social opportunities. This hypothetical distinction of parenting behaviors gains some plausibility from the fact that the latter behaviors, which are definitely overprotective and controlling, are typically found in parents of shy or anxious children [42, 103]. An additional explanation of the link between action orientation and positive child outcomes relies on the possible emotional consequences of action orientation. Action orientation might be related to the experience and the expression of positive affect and to the creation of a general relationship climate of optimism. This assumption derives from the two-factor concept of hope by Snyder and colleagues [92, 93]. Snyder et al. [93] define hope as a cognitive set consisting of agency (the belief that actions can be initiated and sustained) and pathways (the belief that multiple ways can be found to reach one’s goals). It is noticeable that the items Snyder et al. [93] used to measure agency (e.g., “At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals” or “At this time, I am meeting the goals that I have set for myself”) are very similar to the items employed in this study to capture action orientation. Because higher hope (and thus, improved agency) is related to optimism, positive affectivity, higher self-esteem, positive goal expectancies, and lower levels of anxiety [91], high action-oriented mothers and fathers (in contrast to low action-oriented parents) may have easier access to the expression of positive affect and thereby to a more positive, affectionate, and optimistic relationship with their child. This study has some notable limitations. First, the relatively small sample size made it difficult to achieve a desirable balance between the number of free parameters in a model and the number of cases [8]. This limitation is especially evident when the invariance of regression weight between gender groups has to be analyzed. Considering the given circumstances and previous gender specific findings in studies on child social outcomes (e.g., [51, 73, 85]), the possibility of specific effects for sons and daughters demands further inspection. Second, future studies would benefit from the inclusion of the Action Control Scale (ACS) [30, 61]. The ACS was not available at the time of the first data collection of this study, when parents’ action orientation was measured. The ACS consists of three subscales: hesitation versus initiative (difficulty initiating intended goal-directed activities), preoccupation versus disengagement (degree of information processing related to a past, present, or future state), and volatility versus persistence (ability to stay in the action-oriented mode). This trifold measure of action orientation certainly provides more sophisticated insights into the backgrounds of a child’s development. Third, this study investigated long-term correspondence between parents and children in separate models for mothers and fathers. The separate treatment precludes the assessment of the relative importance of mothers or fathers taking the other parent into account [83, 97]. Fourth, and finally, the data of the study, despite their longitudinal composition, are correlational in nature. Thus, the study captures long-term correspondence of parent and child variables, but it does not have the power to actually detect the direction of causal effects. Further research on action control in parents and shyness in children will have to address the causality question and the possibility of reciprocal effects from children to parents in more detail.

6. Conclusions

- The findings of this study demonstrate that future applications of action control theory [55, 60] within the area of the parent-child relationship have the potential to substantially broaden our understanding of socialization processes in general and the socialization of active coping, shyness, and sociability in particular. Apart from theoretical advances, practical benefits may result, as the findings suggest possible perspectives for interventions regarding shyness. In particular, they throw light specifically on the role and the potentials of parents’ ability to initiate action. Improving parents’ action orientation at a very early stage of the child’s development opens up an approach that does not aim to change, primarily or exclusively, the child’s characteristics. Intervention and support could help parents come to understand that their own behavior regulation in ordinary everyday situations may strongly and permanently affect the child’s action control and coping ability. Moreover, the results of this study suggest that the contribution of fathers to the child’s effective coping (and shyness) is as determining a factor as is the contribution of mothers. It is extremely important to demonstrate fathers’ influences such as this, because the view that mothers are the primary and most influential caregiver has dominated not only research on parenting but also public opinion for a long time [78]. In contrast, the findings of this study support the notion of active, less traditional fatherhood.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML