-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(4): 136-145

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.04

Towards Understanding Self-Development Coaching Programs

Khalid Aboalshamat1, 2, Xiang-Yu Hou2, Esben Strodl3

1Dental Public Health, Faculty of Dentistry, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

2Public Health and Social Work School, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia

3School of Psychology, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia

Correspondence to: Khalid Aboalshamat, Dental Public Health, Faculty of Dentistry, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Self-development resources are a popular billion-dollar industry worldwide used to improve individuals quality of lives. However, there are insufficient studies for a contemporary conceptualization, especially when it comes to live self-development programs. This paper provides a literature review about current self-development definitions, ideology, concepts, and themes; quality of material provided; quality and characteristics of self-development providers; and the features of the participants who seek such programs. The paper will also discuss the relationship between self-development and related disciplines including coaching, training, mentoring, and motivational speaking. Finally, a new definition will be proposed for self-development coaching programs. Gaps of knowledge are highlighted for further research.

Keywords: Self-development, Self-help, Human-development, Coaching, Motivational speaking, Psychological well-being

Cite this paper: Khalid Aboalshamat, Xiang-Yu Hou, Esben Strodl, Towards Understanding Self-Development Coaching Programs, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 136-145. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The emergence of self-development books and live programs has been documented since the 1950s [1]. The spreading of this industry is still documented in recent publications [2], but has not yet been investigated in-depth [3, 4]. Self-development is often presented as face-to-face course which can be called self-development live programs (SDLP). Despite the low number of research studies on SDLP, they merit being investigated because of the following. The magnitude of the growing self-development industry has been estimated to be worth billions of dollars [5, 6, 7]. SDLP providers are phenomenally popular and their SDLP course fees range between $1,200 to up to $3,990 U.S. per person [8]. Anthony Robbins, as an example of SDLP providers, today conducts his programs world-wide [9, 10] and has influenced high-ranking, authoritative leaders such as former U.S. president Bill Clinton and the last president of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev [9, 11]. Furthermore, promotional claims accompanying SDLP require critical evaluation. For example, Grant critiqued Robbins’ claims [12] that promise immediate individual’s life improvement as being unproven, psychologically unethical, and perhaps not effective for different population types [13]. More importantly, some catastrophic documented cases of self-development practices should be taken into consideration-for instance, the suicidal case in Sydney Australia of a participant after attending SDLP [14]. Also such case is in the U.S. with a famous SDLP that ended with three participants dying and eighteen being hospitalized [7]. Thus, it is crucial to present this literature review on self-development practices, its effect on quality of life, and identify the gaps in knowledge for future scientific contribution. This paper discusses current definitions, content, providers, main target populations, and impact of SDLP. Any other forms of self-development such as self-development via electronic media or video are beyond the scope of this paper. Furthermore, a brief discussion will try to position self-development among coaching, training, mentoring, and motivational speaking contexts. Finally, a proposed definition for SDLP corresponding with the literature review will be presented as an attempt to understand SDLP.

2. Methodology

- This review was done by searching electronic databases to find relative literature. We searched Queensland University of Technology electronic library, Science Direct, PubMed, and Google scholar for peer-reviewed articles and books on self-development programs since January 1990 up to January 2014. The reference lists in primary sources were also searched for relevant articles. Other commercial websites of self-development and newspaper articles on self-development were only used to provide examples of support. Searched terms used combinations of self-development, self-improvement, self-help, coaching, mentoring, training, motivational speaking, course, program, books, psychological health, mental health, quality of life, and improvement. Due to scarcity of scientific articles, all resources on self-development written in English were eligible in this review, but only relevant literature were included. The articles investigated self-help activities administrated by psychologists or psychiatrists were excluded. Self-development via electronic media or videos were also excluded.

3. What is Self-development?

- There is variability among self-development terms and definitions in the literature along with an overlap with other disciplines. The term “self-development” is not the common used in literature. Instead, self-development has been expressed by different terms such as self-help, self-improvement [5], self-help resources [15], self-help, self-guided improvement [16], public self-help [17], and self-development [18]. All these terms were used in the literature without an agreement on a unified term.Self-development also has different definitions. For instance, the APA Dictionary of Psychology defines self-help as "a self-guided improvement economically, intellectually, or emotionally often with a substantial psychological basis" and explains that self-development activities aim to improve aspects of life that professionals do not typically apply themselves to, such as: friendship, identity, and life skills [16]. This definition illustrates that self-development aims to improve individuals in different areas, but fails to distinguish self-development from other disciplines by providing details on ways of delivery or the providers. Another definition is "adopting book or computer CD-ROM formats…based upon many of the principles and techniques incorporated within conventional psychological therapies, with many of the more recent self-help resources adopting a cognitive-behavioral or problem-solving approach" [19]. This definition extends the scope of self-development into a psychological therapeutic spectrum resulting in an overlap between self-development and bibliotherapy, which is a psychological treatment approach using guided reading as a therapy and written by psychologists. In fact, a number of authors illustrate the necessity of differentiating the commercial self-development books and materials from other psychological treatment terms [20, 21] and other disciplines such as coaching [22] so as not to mislead clients. These limitations raise the need to review literatures upon different aspects of SDLP and to compare it with similar disciplines for better conceptualization as the following.

4. Self-development Content

- To understand self-development, its ideology and concept, themes and the quality of materials provided should be discussed. In 2004, a study investigated a self-development book, If Life is a Game These are the Rules [23], and found that self-development books use a combination of holistic life view and spiritual ideology characterized by secular spiritual attitudes that tend to make individuals concentrate on "the self" [24]. Other studies indicated that some self-development materials were derived from cognitive behavioral therapy concepts [13], Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP; Robbins, 1997), and positive psychology [25]. Accordingly, self-development multiplies suggested to have variable ideologies and conceptual frameworks, which makes the researcher’s task more difficult to investigate in depth. However, and though the diversity of these concepts and ideologies, they all aim to promote personal improvement to the client. A qualitative study of 57 best-selling self-development books identified five main themes—personal growth, personal relationships, coping with stress, identity and miscellaneous—that included different topics such as study skills for students, hypnosis, communication skills, and dealing with depression [25]. In another study, 134 self-development readers in Canada were found to use self-development mainly to improve their health and well-being in addition to interpersonal skills and personal-career [26]. This study’s findings coincide with the overall earlier definitions of self-development as both used a wide range of life areas to improve individuals' lives including the health aspects. Nevertheless, these studies did not specify very precisely how this improvement takes place, the attitude of each theme, or even provide a unified model. It is rather suggested that each self-development book or program adopt the writer or the provider’s perspective. From another perspective, the validity of the materials presented as scientific evidence in SDLP are questionable [27]. There is some literature that indicates a mixture of intact and quality information, unproven or misleading content. For example, Grant (2001a) investigated the scientific background of the six steps of Neuro-Associative Conditioning (NAC) which is a technique used by Anthony Robbins. Grant found that four steps have roots in philosophical or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) concepts. However, the other two steps are not yet proven. An example of misleading information is when The National Council Against Health Fraud critiqued the 10th chapter of Robbins's book [12] and argued that it contained many misconceptions and half-facts about diet, eating, and food [28]. This indicated that the material presented within self-development books or SDLP to improve lives or health are not critically evaluated, and need further research investigation especially for the other books and programs than might have influence on population levels.It is also important to emphasize that the previous examples are derived from literature about self-development books whereas such investigations on SDLP were not specifically found. Nevertheless, it can be suggested that SDLP shares the above-mentioned features for the following reasons. It can be observed from famous self-development coaches' websites, brochures and advertisements that the content of self-development books and live programs are alike because the books' authors are the coaches/trainers of their own self-development courses such [12] who used the content of his books in his self-development programs [13]. Thus, it is suggested that self-development books and live programs have the same structure. However, there is a need for more structural qualitative and qualitative studies to investigate SDLP contents specifically.

5. Self-development Providers

- The following section will discuss self-development providers' backgrounds and their characteristics. An analysis of the literature indicates that self-development providers' backgrounds and qualifications are not clearly discussed by authors and are sometimes deceptive. Fernros's describes the self-development program provider in his study in Sweden as a specialist according to the provider’s reputation and life-long expertise only in facilitating this program [29]. In another study on another program in Australia, the authors neglect to illustrate the local leader’s credential or characteristics [30].It is also reported that commercial self-development authors use irrelevant Dr. and PhD titles to situate themselves as experts and to add credibility to their works [4]. These examples indicate the presence of self-development writers, coaches, or providers with questionable qualifications in relation to the materials they present. Moreover, SDLP provider characteristics are highlighted as an important factor for the program's effectiveness [27]. This was indicated by Several authors indicated for a number of these characteristics includes being famous, having a good reputation, and being seen as an authority brands self-development providers as experts in their field [31], even if that is not true [32]. In addition, empathy [33, 34], confidence, using the provider's personal experience [34], persuasiveness [7, 25], the ability to get the audience’s attention [35, 36] and the ability to influence clients' emotions [37] are all highlighted as characteristics for successful self-development providers. Two other factors were highlighted by the coaching literature which are acting as a role model and increasing the motivational level for participants [38], which can also be included as important features. Other characteristics of the SDLP itself can influence the program's outcomes such as the program's relevance to the coachee [39], the coachees having experience with the programs contents [40], and their level of satisfaction [41]. These characteristics, were reported scatteredly in the previous studies and did not receive valuable attention as susceptible contributing factors to such programs’ outcomes, and have only investigated empirically in one solo pilot study where the author indicated that self-development coach characteristics rating, by participates, was above the normal average rating of the normal population [42]. This encourages to investigate theoretically and empirically the different characteristics that may play a vital role in such programs’ effects.The role of SDLP providers constitutes a knowledge gap of in that it is not significantly discussed in literature. However, it is observed that SDLP providers teach the program materials, facilitate the exercises, and interact with participants employing the discussed characteristics to achieve individual development and improvement.

6. Self-development Participants

- Reviewing the literature indicates a number of specific features of people who attend SDLP. Fernros et al. (2005) found that people who attend the program score poorer in all quality of life and emotional well-being subclasses when compared to the general population. Moreover, the authors found a significant association between emotional health and program enrolment, implying that the lower the emotional health, the greater people intention to attend and fund themselves for these programs. This association can be explained by attendees’ desire to improve their well-being, which flows logically with the self-development’s main intention —to improve an individual's life. However, this finding might not apply to everyone attending such programs. For instance, people might attend as part of a luxurious lifestyle as has been found on an organizational scale in relation to developmental programs [43]. Such contradictory information widens the horizon to conduct more research on clients' intentions and motives for attending and paying for such programs. On the other hand, other literature revealed some concrete demographic features of people attending self-development programs. In relation to gender, females have a more positive attitude toward self-development books [44] and programs [7, 45] in the U.S and Australia. This finding is coincidence with the previous statement of clients with low quality of life, as females usually have a poorer quality of life compared to males [46, 47].From an educational point of view, Fernros et al. (2005) also found that the programs' attendee were at twice the national educational level of the population. Conversely, a recent study in Austria found that educated people are less prone to take action from self-development to improve their lives [2]. This controversial finding might be explained by the diversity of self-development programs and providers’ characteristics whereby each program and provider can target a specific type of population and reflect another gap in knowledge.

7. The Empirical Impact of SDLP on Quality of Life

- According to our knowledge, only two studies investigated the commercial SDLP empirically whereas some investigated other SDLP that were designed for research purposes only. Fernros (2008) investigated the effect of a SDLP which has been presented since 1985 empirically with control group in Sweden. The program included exclusive techniques, bodily exercises, reflection, meditation, birth exercise, death exercise, freedom exercise, and bully-victim roles. Fernros found a significant improvement in the sense of coherence and in most of the health related quality of life domains including emotional well-being, emotion, pain and sleep. The other one was a pilot study that was conducted on 17 medical students in Saudi Arabia empirically using SDLP of study skills that has been used since 2008. The study found significant improvement in depression, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction [42]. These results encourage for more investigation for the other programs because these results are not enough to validate such programs especially when there are a wide varieties of SDLP.

8. Self-Development Live Program in Relation to Other Research Constructs

- When investigating self-development, it is very important to discuss self-development in comparison to other terms in the literature for better understanding and to avoid overlap with other disciplines. The second section of the paper will discuss briefly the relation between SDLP and coaching, training, mentoring, and motivational speaking. Coaching will be discussed in more detail as it is most similar to self-development in regard to its definition, aims, approaches, types, and content, and its relation to self-development. Training, mentoring and motivational speaking will be discussed briefly in terms of self-development. It should be highlighted that there is a great overlap between coaching, training, and mentoring [48]. Despite differentiation efforts, the boundaries are still hazy and part of an ongoing argument. Moreover, training, coaching, and mentoring share the same concepts and are typically seen as interchangeable elements of a learning process [49]. This might make the comparison more complex, but the discussion in this paper will try to position self-development in the arena of research with more comparable manner.

8.1. Self-development versus Coaching

8.1.1. Definition

- Coaching could be the field closest to live self-development programs. To illustrate that, it is important first to provide a brief overview. Coaching is a term that has emerged recently in the research arena with consistent efforts to develop a related body of knowledge [48, 50]. Coaching definitions varies from author to author with some variability [48, 49, 51]. Cox and colleagues in their seminal work, The Complete Handbook of Coaching, defined coaching as "a human development process that involves structured, focused interaction and the use of appropriate strategies, tools and techniques to promote desirable and sustainable change for the benefit of the coachee and potentially for other stakeholders" [48]. Though Cox and colleagues explained that their definition is not completed yet, it can be considered the best-published definition. Other definitions, in table 1, add that coaching also aims for immediate change or improvement in the performance, development, learning, life experience, and personal or professional growth. Thus, SDLP apparently coincides with coaching’s aim to improve and develop individuals multidimensionally.

8.1.2. The Coach and SDLP Provider

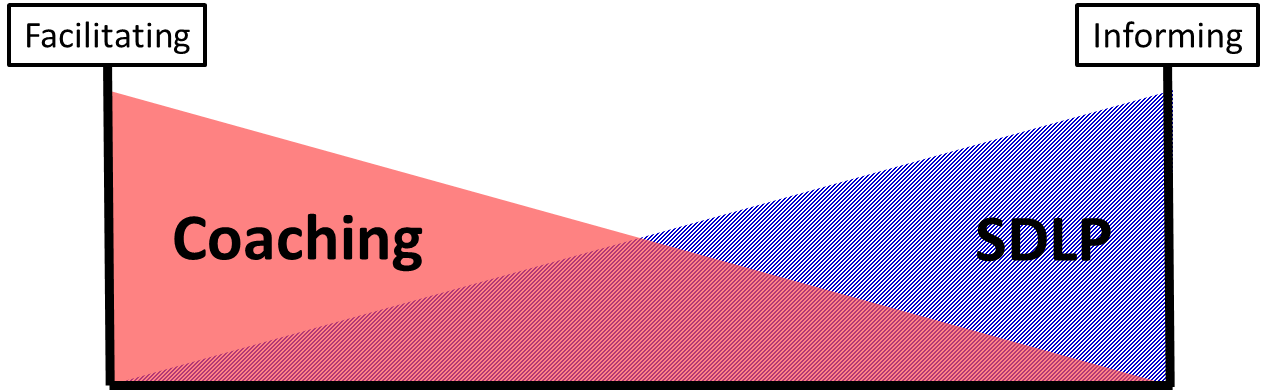

- The coach’s role is considered an integral core value of the coaching process as the coach facilitates, guides, and helps the coachee toward self-direct learning [52, 55]. However, other authors in table 1 mentioned different roles and approaches including "tutoring," "instructing," "helping," "interaction," and "collaborative relationship." These roles reflect that coaching is a broader concept than just facilitation, and reveal an unresolved argument on the coach’s role by different key authors.An interesting explanation for this agreement is proposed by Cavanagh, Grant and Kemp [56], who indicate that the coach facilitates self-directed learning but can also move into a "teaching" mood when appropriate. This notion corresponds with a number of interventional studies where coaching involves informative sessions in addition to the facilitation process [42, 55, 57, 58]. In contrast, SDLP can be considered mainly informative and teaching conjugated with facilitation process, i.e., both coaching and self-development take the approach of facilitating and informing, but with different grades as in figure 1.

| Figure 1. The overlap between self-development live program and coaching approaches |

8.1.3. Content

- There are three aspects that will be discussed here to further compare between coaching and self-development: concepts, themes, and the quality of material provided. Coaching ideology is seen to be derived from the Western culture in the process of pursuing self-centered goals and values [64], while some self-development also has a self-centered attitude in addition to holistic life ideation as discussed earlier by Fernros et al. This reflects that self-development tend to conjugate somewhere in the spiritual dimension regardless of its being subject to science. Moreover, Cox and colleagues discussed 13 concepts used in coaching, which are: psychodynamic, cognitive behavioral, solution-focused, person-centered, gestalt, existential, ontological, narrative, cognitive-developmental, transpersonal, positive psychology, transactional analysis, and Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) approaches [48]. The authors illustrated that these are not the only concepts or approaches and critiqued other authors who exclude some approaches that they are not familiar with. In this context, the standard self-development live program approach is not very clear, as it rather depends on the provider’s style in conducting the program. However, NLP, positive psychology and CBT concepts have been reported to be used within SDLP. This ambiguous information results from the fact that coaching research tends to outline and articulate its theoretical frameworks and approaches, while the self-development field is seen as being more chaotic and commercial practice.In 2010, Grant indicated that the principles of coaching allow it to be applied to any field desired by the client in order to achieve goals in any field. However, this notion does not correspond with the classifications of skills and performance, developmental, executive and leadership, managerial, team, peer, career, and life coaching as themes of improvement [48]. This classification shows how coaching is directed into specific fields more than being applied to any field. Furthermore, authors in the field explain that coaching concepts come from other disciplines such as psychology, education, behavioral sciences, clinical counseling, teaching, workplace training, learning and development, management and economics because coaching is a new field that uses other disciplines' concepts [56]. Indeed, this indicates that coaching might be directed within different contexts and themes. On the other hand, self-development themes, as discussed before, have different nature of classification into specific topics that focuses more on individual perspectives. Nevertheless, the life coaching concept is more similar to SDLP, as life coaching concerns with the individual to improve performance, well-being, and to achieve goals [22]. It is also interesting to note also that life coaching started as a commercial coaching in the 70s and 80s [22]. However, some observed that SDLP is directed toward other themes of coaching such as leadership and management, which indicates that SDLP and coaching are not contradicting in this point.From another perspective, and despite the rigorous efforts done by some author to move coaching into evidence-based practices [51, 56, 65, 66], achieving evidence-based coaching has a very long way to go and needs efforts to adopt from other disciplines [22]. For instance, NLP has been highlighted as a very popular approach used by coaches [67]. Grimley discussed NLP as a model that emerge from Richard Bandler and John Grinder and their observations, where a current effort is conducted to find the scientific frameworks behind it and to evaluate it more critically. However, a recent systemic review concluded that there is only little evidence to support the effectiveness of NLP [68]. In other words, it is common to find un-evidence based approaches in coaching and not all coaching in practice are evidence-based. In the same manner, self-development contains knowledge from other disciplines and not all the information provided is scientifically proven as discussed before. It is relevant to remind that SDLP use also NLP concepts as well. Thus, the main difference here might be that coaching scholars are conducting rigorous efforts to move coaching to be an evidence-based practice, while self-development providers are not so concerned with this. It can be concluded that self-development and coaching sharing many aspects, though researcher try to distinguish coaching with a number of boundaries. Coaching can be viewed as the new scientific movement of the current unorganized practices in the commercial world of SDLP, as coaching is sharing multiple aspect and root within SDLP. Thus, this paper proposes considering SDLP as a theme with specific features among the coaching themes and call it self-development coaching.

8.2. Self-development versus Training

- Self-development shares some features with training, but some of these features overlap with coaching as well. The following part will discuss briefly the main points. Training is defined as "learning that is provided in order to improve performance on the present job" [69]. Another definition is "any organized activity that is designed to bring about change in an employee's on-the-job-skills, knowledge, or attitudes to meet a specific need of the organization" [70]. Training is considered as a part of technical vocation or as an organizational-developmental process for employees [71]. Also, the main aim of training is inducing an organizational change by improving an individual’s competency to the required level [72]. This illustrates that training is more organizational-centered, through this is achieved by changing individuals to develop the organization competency. On the other hand, self-development is client-centered mainly, even if that extended secondary to the organization benefit as explained earlier. This can result in different individual desires, attitudes, relevance and scope of change between trainee and self-development participants.From another perspective, Grant (2001b) tried to differentiate between coaching, mentoring, and training. He stated that training is more rigid and demands trainees to adjust themselves to the training process and the course, whereas coaching is more flexible and could be adjusted to coachee interest. According to the previous statement, self-development is considered more relevant to training as self-development usually has a pre-designed program concerning specific topics to which the participants need to adjust themselves.However, it is very important to notice that this explanation by Grant does not mean that the current coaching approach is isolated from the training approach. As explained earlier, coaching empirical studies involved "informative" fixed activities besides coaching [57, 58]. This can be understood in the context of the overlap between coaching and training [48, 49]. In addition, self-development usually has more room for freedom for the participants to use the provided material or not, and usually is not followed by assessments such as in training [73]. Thus SDLP is in the middle of the rigidity of training and the flexibility of coaching. Another interesting point is that SDLP outcomes can be categorized into knowledge, skills, and attitude according to McArdle's definition of training and Kraiger’s model of training outcomes [73]. This is because SDLP provides information (such the importance of goal setting), strategies (such as SMART technique for goal setting), and values (such as being proactive). However, this does not mean that SDLP is exclusively a training concept, because many educational processes, including coaching and mentoring, can include these outcomes. In fact, these outcomes are the same as those of Bloom’s Taxonomy [74] of the general educational activities which are cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. Nevertheless, this addition could be useful to understanding SDLP, because training is a more mature discipline than SDLP that needs to develop strong theoretical frameworks. The previous section illustrates that SDLP shares the program's pre-designed feature with training and can be explained by Kraiger's model of training. However, this feature is sometimes seen as overlapping with coaching as well. SDLP has both coaching and training features, yet is more liable to be categorized under the coaching umbrella due to the several common factors.

8.3. Self-development versus Mentoring

- Mentoring is defined as "an interaction between at least two people, in which the knowledge, experience and skills of one or both are shared, leading to growth and self-understanding" [49]. In addition, mentoring can be characterized as informal relationship between two person where the mentor is more knowledgeable than the mentee [75]. This does not follow with the general self-development practice where SDLP is not one to one relationship occasionally.Furthermore, Law and colleagues (2007) illustrated that mentoring is a long-term relationship with the mentee [49]. When it comes to self-development it is more likely to be a short-term relationship that varies from days with famous providers up to months in some programs [18, 29]. This is considered to be the second major difference between self-development and mentoring, and is seen as another shared feature with coaching as coaching is also a short-term relationship [49]Nevertheless, a mentor is required to be a senior or a very experienced and knowledgeable person in the selected field [55, 76]. This point is similar to self-development providers who are recognized or acknowledged in the field. Therefore, self-development provider is closer to mentoring in this point. Thus, it is suggested that self-development again shares some features with mentoring but does not follow mentoring notions in general, fostering the idea that SDLP is more relevant to a coaching concept. It is worth mentioning that SDLP is observed to sometimes transfer into a one-to-one mentoring relationship, but not as a common trend.

8.4. Self-development versus Motivational Speaking

- Motivational speaking is another common commercial description to SDLP. However, motivational speaking as a term is barely mentioned in scientific literature. Instead, public speaking is the term commonly used, which is defined as "a sustained formal presentation made by a speaker to an Audience"[77]. In fact, motivation is seen as one feature of an effective public speaking when combined with informing, influencing, persuasion, leadership, mass communication, and customer service [78]. Thus, it is better to discuss SDLP in relation to public speaking as a term rather than the common, but incomprehensive term of motivational speaking.As previously mentioned, public speaking and SDLP share some features but differ in others. SDLP’s implementation aligns with public speaking's definition in general. However, the formal presenting style of public speaking can be extended in SDLP into interactive activities and exercises during the program. Also, public speaking and SDLP share some features such as motivation, informing, influencing and persuasion, while not sharing other features. For example, SDLP does not always necessitate mass communication as the program can be conducted on small number of participants. Furthermore, SDLP has an integral aim of improving individuals' lives, whereas public speaking can be employed for other aims such as politics or marketing speeches. SDLP also, can include more detailed knowledge and skills, such as goal setting strategies and exercises, to help the client induce change in contrast to public speaking. In fact, public speaking is seen as a skill or a form of communication rather than a discipline in comparison to SDLP or coaching. Thus, SDLP can include the features of public speaking fully or partially during the SDLP program, but SDLP is a larger interactive process than merely public speaking.

8.5. A Proposed Definition for Self-development Coaching Program

- According to this review of the self-development literature, we suggested a new definition of self-development and used it in a recent interventional study [42]. The self-development coaching program can be defined as a "short term interactive human developmental process, between coachees and a recognized and featured coach. This process aims to facilitate individuals' life improvement in knowledge, skill or attitude in fields valued by the coachee, which potentially extend to the organization. This is achieved by a mixture of concept and techniques derived from other disciplines and from the coach's personal experience delivered in a semi-rigid structured program." It should also be noted also that the word "self" in the term self-improvement indicates the flexibility and freedom of the coachee to use the material provided or not. This definition is characterized by flexibility in terms of the number of participants, program concepts, and coach's characteristics as these factors can vary from one program to another. Nevertheless, this definition can be used as a starting point for a further qualitative research to refine the conceptual identity of self-development coaching program when future literatures and theories are conducted and developed.Adopting this proposed definition has three advantages. First, using the unified term of self-development coaching program amidst other disciplines' definitions will reduce the overlap while conducting research on these fields. This term aligns with the previous self-development definitions in addition to including more details about the aim, provider, topics, approach, and participants. The definition in this form also does not overlap with that of psychologist-led bibliotherapy. Further, the definition is similar to other coaching definitions [48; 50] but illustrates the importance of the coach’s characteristics, as discussed earlier, and highlights the variable quality of material provided in this type of coaching. This definition is differentiated from that of training as this type of coaching is client-centered and the structure of the program is not completely rigid. Finally, this definition shows that the self-development coaching program is a short-term process in contrast with mentoring. Second, this definition will help coaching researchers to prevent overlapping research data between evidence-based coaching and the commercial self-development coaching program. This is important in view of the explicit efforts of coaching research to build a body of knowledge with scientific conceptual theories about coaching and tendency to avoid the commercial self-development coaching program. Third, this definition highlights this type of coaching in the research area as a knowledge gap that needs researchers' evaluation and critiques in light of its wide-spread use and market share.

9. Conclusions

- Despite self-development's popularity and large industry, high costs, un-evidenced claims, and case-reports of its hazards insufficient publications and resources are found for comprehensive understanding and evaluating of the field. Current definitions were insufficient to provide an accurate description of self-development live programs (SDLP). The review indicated that some SDLP featured secular-spiritual ideation while some borrowed concepts from other disciplines. SDLP themes vary but aim to improve and develop individuals in different fields. The contents are a mixture of proven, unproven and sometimes misleading information. Providers are not always academically qualified, but rather are recognized by the clients and characterized by special characteristics that facilitate participants’ improvement. Moreover, people who attend SDLP might be characterized as having a poor quality of life or poor psychological health, or may simply aim to have luxurious experiences. Females have been found to be more open to self-development, whereas the findings on education level in relation to clients were inconclusive. Moreover, very few empirical evidences was found indicated to the significant improvement of participants’ quality of life, however, not enough to draw a firm conclusion.When comparing SDLP with other disciplines, it is found that SDLP shares a number of features with coaching, training, mentoring, and motivational speaking. However, self-development can be considered a coaching category because both self-development and coaching are mainly client-centered and share the same aim of improving and developing individuals by facilitating and informing, they sometimes uses the same concepts, and are both short term processes. Though SDLP is a more rigid and fixed program such as in training, conducted by a knowledgeable provider such as in mentoring, and using the skills of public and motivational speakers, the concept of self-development is closer to coaching’s main features and suggested to be termed self-development coaching. Therefore, a new definition of self-development coaching program was proposed based on the previous findings. Nevertheless, and because of the scarcity of literature and the diversity of the self-development genre, this definition can act only as an initial attempt to define self-development coaching program as the definition need a critical evaluation when more literatures are developed. The literature review reveals from the common and overlapping information that the self-development coaching program is the pre-research phase of the commercial coaching-training-mentoring mixture. It is crucial not to isolate the current practice of self-development from the research arena. It is necessary to assess self-development coaching programs’ effectiveness and validity to be able to incorporate useful practices and omit pseudo or ineffective practices. This can provide vital practical data to help people attain a healthier and more satisfied life, which will in turn develop coaching science and also promote public health awareness and public policy development for eliminating deceptive and inaccurate practices in future. The self-development coaching program also has room for flexibility to combine coaching, training, mentoring, and public speaking to improve individuals. This synergetic and realistic view of current practices can resolve the dilemma of the failed efforts to isolate these terms in research. The major limitation of this paper is the scarcity of scientific publications on self-development coaching programs. This limited our attempt to provide an integrated discussion between different studies results. In fact, the current quantity and quality of literature in addition to the highlighted research gaps indicated for immature and insufficient body of knowledge to have considerable understanding to self-development coaching programs, and urge for further qualitative and quantitative research.

References

| [1] | Fried, S. (1994). American popular psychology: An interdisciplinary research guide. New York: Garland. |

| [2] | Holzinger, A., Matschinger, H., & Angermeyer, M. (2012). What to do about depression? Self-help recommendations of the public. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(4), 343-349. |

| [3] | Farrand, P. (2005). Development of a supported self-help book prescription scheme in primary care. Primary Care Mental Health, 3(1), 61-66. |

| [4] | McKendree-Smith, N., Floyd, M., & Scogin, F. (2003). Self administered treatments for depression: A review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(3), 275-288. |

| [5] | McGee, M. (2005). Self-help, inc: Makeover culture in American life. Huntington Beach, CA: Oxford University Press, USA. |

| [6] | BBC. (2009). Self-help 'makes you feel worse. Retrieved September 14, 2011, fromhttp://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8132857.stm. |

| [7] | Nathan, T. (2011). Change we can (almost) believe in, Time. Retrieved fromhttp://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2055188,00.html. |

| [8] | PR Newswire. (Jan 25, 2008). How a 29-year-old kid got free tickets to thousand dollar events by Tony Robbins, Jack Canfield, James Ray, Debbie Ford, Harv Eker and other celebrity speakers without Spending a dime: And why he's giving them all away for FREE, PR Newswire. Retrieved fromhttp://gateway.library.qut.edu.au/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/docview/453271513?accountid=13380. |

| [9] | Yentob, A. (2008). The secret of life., BBC. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/imagine/episode/the_secret_of_life.shtml. |

| [10] | Stein, J. (2010). Kiss my hand, please! Time, 175(5), 60. |

| [11] | De Witt, K. (1995). Dial 1-800-My-GURU. The New York Times, 5. |

| [12] | Robbins, A. (1992). Awaken the giant within: How to take immediate control of your mental, emotional, physical and financial destiny. New York: Free Press. |

| [13] | Grant, A. (2001). Grounded in science or based on hype? An analysis of neuro-associative conditioning. Australian Psychologist, 36(3), 232-238. |

| [14] | The Spectator. (2009). Self-help course led woman to deadly leap; Coroner says Turning Point seminar caused woman, 34, to kill herself in Sydney, The Spectator, p. 15. Retrieved from http://qut.summon.serialssolutions.com. |

| [15] | Williams, C. (2003). Overcoming depression: A practical workbook. A five areas approach. London: Arnold. |

| [16] | VandenBos, G. R., & American Psychological Association. (2007). APA dictionary of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. |

| [17] | Holzinger, A., Matschinger, H., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2011). What to do about depression? Self-help recommendations of the public. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. |

| [18] | Holm, M., Tyssen, R., Stordal, K., & Haver, B. (2010). Self-development groups reduce medical school stress: A controlled intervention study. BMC Medical Education, 10(1), 23. |

| [19] | Williams, C. (2003). Overcoming Depression: a Practical Workbook. A Five Areas Approach. London: Arnold. |

| [20] | Mcallister, R. J. (2007). Emotions: Mystery Or Madness: AuthorHouse. |

| [21] | McKendree Smith, N. L., Floyd, M., & Scogin, F. R. (2003). Self administered treatments for depression: A review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(3), 275-288. |

| [22] | Grant, A., & Cavanagh, M. (2010). Life Coaching. In E. Cox, T. Bachkirova & D. Clutterbuck (Eds.), The complete handbook of coaching (pp. 287-390). London: Sage Publications. |

| [23] | Carter-Scott, C. (1999). If life is a game these are the r. London: Hodder & Stoughton. |

| [24] | Askehave, I. (2004). If language is a game-these are the rules: A search into the rhetoric of the spiritual self-help book if life is a game these are the rules. Discourse & Society, 15(1), 5. |

| [25] | Bergsma, A. (2008). Do self-help books help? Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(3), 341-360. |

| [26] | McLean, S., & Vermeylen, L. (2013). Transitions and pathways: Self-help reading and informal adult learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education(ahead-of-print), 1-16. |

| [27] | Ramones, S. M. (2011). Unleashing the power: Anthony Robbins, positive psychology, and the quest for human flourishing. Master of Applied Positive Psychology, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved fromhttp://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=mapp_capstone. |

| [28] | Jarvis, W. (2003). Anthony Robbins. National Council Against Health Fraud Retrieved fromhttp://www.ncahf.org/articles/o-r/robbins.html. |

| [29] | Fernros, L., Furhoff, A., & Wändell, P. (2008). Improving quality of life using compound mind-body therapies: Evaluation of a course intervention with body movement and breath therapy, guided imagery, chakra experiencing and mindfulness meditation. Quality of life research, 17(3), 367-376. |

| [30] | Muenchberger, H., Kendall, E., Kennedy, A., & Charker, J. (2011). Living with brain injury in the community: Outcomes from a community-based self-management support (CB-SMS) programme in Australia. Brain Injury, 25(1), 23-34. |

| [31] | Zimmerman, T., Holm, K., & Haddock, S. (2001). A decade of advice for women and men in the best selling self help literature. Family Relations, 50(2), 122-133. |

| [32] | Mcallister, R. (2007). Emotions: Mystery or madness. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. |

| [33] | Lucock, M., Barber, R., Jones, A., Lovell, J., & Barczi, M. (2007). Service users' views of self-help strategies and research in the UK. Journal of Mental Health, 16(6), 795-805. |

| [34] | Hall, D., Otazo, K., & Hollenbeck, G. (1999). Behind closed doors: What really happens in executive coaching. Organizational Dynamics, 27(3), 39-53. |

| [35] | Walters, L. (1993). Secrets of successful speakers. New York: McGraw-Hill. |

| [36] | Richardson, R., Richards, D. A., & Barkham, M. (2008). Self-help books for people with depression: A scoping review. Journal of Mental Health, 17(5), 543-552. |

| [37] | Passmore, J. (2008). The character of workplace coaching: The implications for coaching training and practice. Unpublished doctoral thesis. |

| [38] | Bass, B., & Avolio, B. (2000). Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden. |

| [39] | Beckert, L., Wilkinson, T. J., & Sainsbury, R. (2003). A needs-based study and examination skills course improves students' performance. Medical Education, 37(5), 424-428. |

| [40] | Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. |

| [41] | Schmidt, S. (2007). The relationship between satisfaction with workplace training and overall job satisfaction. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 18(4), 481-498. |

| [42] | Aboalshamat, K., Hou, X.-Y., & Strodl, E. (2013). Improving Dental and Medical Students’ Psychological Health using a Self-Development Coaching Program: A Pilot Study. Journal of Advanced Medical Research (JAMR), 3(3), 45-57. |

| [43] | Kumpikaite, V. (2008). Human resource development in learning organization. Journal of business economics and management, 9(1), 25-31. |

| [44] | Wilson, D., & Cash, T. (2000). Who reads self-help books? Development and validation of the self-help reading attitudes survey. Personality and individual differences, 29(1), 119-129. |

| [45] | Grant, A. (2004). Executive, workplace and life coaching: Findings from a large-scale survey of International Coach Federation members. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 2(2), 1-15. |

| [46] | Bonsaksen, T. (2012). Exploring gender differences in quality of life. Mental Health Review Journal, 17(1), 39-49. |

| [47] | Bisegger, C., Cloetta, B., von Bisegger, U., Abel, T., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2005). Health-related quality of life: Gender differences in childhood and adolescence. Sozial-und Präventivmedizin, 50(5), 281-291. |

| [48] | Cox, E., Bachkirova, T., & Clutterbuck, D. (2010). The complete handbook of coaching. London: Sage Publications. |

| [49] | Law, H., Ireland, S., & Hussain, Z. (2007). The psychology of coaching, mentoring and learning. West Sussex: John Wiley. |

| [50] | Grant, A., Cavangh, M., & Parker, H. (2010). The state of play in coaching today: A comprehensive review of the field. In G. Hodgkinson & J. Ford (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 25): Wiley & Sons Ltd. |

| [51] | Stober, D., & Grant, A. (2006). Evidence based coaching handbook: Putting best practices to work for your clients. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley. |

| [52] | Whitmore, J. (1992). Coaching for performance. London: Nicholas Brealey. |

| [53] | Parsloe, E. (1995). Coaching, mentoring, and assessing: A practical guide to developing competence. New York: Kogan Page. |

| [54] | Downey, M. (1999). Effective coaching. London: Orion Business Books. |

| [55] | Grant, A. (2001). Towards a psychology of coaching. PhD, Macquarie University, Sydney. Retrieved fromhttp://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED478147.pdf. |

| [56] | Cavanagh, M. J., Grant, A., & Kemp, T. (2005). Evidence-based coaching. Brisbane: Australian Academic Press. |

| [57] | Grant, A., Curtayne, L., & Burton, G. (2009). Executive coaching enhances goal attainment, resilience and workplace well-being: A randomised controlled study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), 396-407. |

| [58] | Miller, W., Yahne, C., Moyers, T., Martinez, J., & Pirritano, M. (2004). A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1050. |

| [59] | Grant, A., & O’Hara, B. (2008). Key characteristics of the commercial Australian executive coach training industry. International Coaching Psychology Review, 3(1), 57. |

| [60] | Grant, A., & Cavanagh, M. J. (2007). Coaching psychology: How did we get here and where are we going? InPsych: The Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society Ltd, 29(3), 6-9. |

| [61] | Sherman, S., & Freas, A. (2004). The wild west of executive coaching. Harvard Business Review, 82(11), 82-93. |

| [62] | Robbins, A. (2011). Anthony Robbins. Retrieved April 23, 2013, from http://www.tonyrobbins.com/biography.php |

| [63] | Brown, L. (2011). Meet Les Brown Retrieved April 23, 2013, fromhttp://lesbrown.org/lesbrown.com/lesbrown.com/english/meet_lesbrown.html. |

| [64] | Geber, H., & Keane, M. (2013). Extending the worldview of coaching research and practice in Southern Africa: The concept of Ubuntu. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 11(2), 8-16. |

| [65] | Grant, A., & Cavangh, M. (2007). Evidence-based coaching: Flourishing or languishing? Australian Psychologist, 42(4), 239-254. |

| [66] | Green, S., Grant, A., & Rynsaardt, J. (2007). Evidence-based life coaching for senior high school students: Building hardiness and hope. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2(1), 24-32. |

| [67] | Grimley, B. (2010). The NLP Approach to Coaching. In E. Cox, T. Bachkirova & D. Clutterbuck (Eds.), The complete handbook of coaching (pp. 185-199). London: Sage Publications. |

| [68] | Sturt, J., Ali, S., Robertson, W., Metcalfe, D., Grove, A., Bourne, C., & Bridle, C. (2012). Neurolinguistic programming: A systematic review of the effects on health outcomes. British Journal of General Practice, 62(604), e757-e764. |

| [69] | Nadeler, Z. (Ed.). (1984). The handbook of human resource development. New York John Wiley and sons. |

| [70] | McArdle, G. (1989). What is training? Performance Improvement, 28(6), 34-35. |

| [71] | Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. (2001). The science of training: A decade of progress. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 471-499. |

| [72] | Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S., Kraiger, K., & Smith-Jentsch, K. (2012). The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice. Psychological science in the public interest, 13(2), 74-101. |

| [73] | Kraiger, K., Ford, J., & Salas, E. (1993). Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 311. |

| [74] | Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay, 19, 56. |

| [75] | Clutterbuck, D., & Megginson, D. (2006). Mentoring in action: A practical guide for managers. London: Kogan Page. |

| [76] | Garvey, B. (2010). Mentoring in coaching world. In E. Cox, T. Bachkirova & D. Clutterbuck (Eds.), The complete handbook of coaching (pp. 287-390). London: Sage Publications. |

| [77] | Sellnow, D. D. (2005). Confident public speaking. California: Wadsworth. |

| [78] | Anburaj, G., & Rajkumar, A. D. (2012). The art of public speaking. Journal of Radix International Educational and Research Consortium, 1(11), 1-13. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML