-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(4): 128-135

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.03

Consumer Cognitive Dissonance Behavior in Grocery Shopping

Anna-Carin Nordvall

Umea School of Business and Economics, Umea University, 901 87, Sweden

Correspondence to: Anna-Carin Nordvall, Umea School of Business and Economics, Umea University, 901 87, Sweden.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Cognitive dissonance occurs when people have to choose between two equally attractive goods. The unpleasant feeling, in turn, leads to a consequent pressure to reduce it. However, the strong interest in food in consumers’ life makes the line between high and low involvement purchases indistinct where also grocery shopping could trigger cognitive dissonance. In this research 100 males and females performed a virtual shopping spree using rate – choose – rate again. In accordance with previous studies, the results showed that participants did give a more favorable score for chosen items. Contradicting to previous research, the results showed that cognitive dissonance occur even for goods categorized as low involvement purchases.

Keywords: Cognitive dissonance, Consumer decision making, Mental processes, Emotion, Organic food

Cite this paper: Anna-Carin Nordvall, Consumer Cognitive Dissonance Behavior in Grocery Shopping, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 128-135. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140404.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Consumers’ has in the recent years start paying more attention to their food consumption behavior and are more peculiar than ever of their eating habits [16]. The choice of what to consume includes considerations of health and environment among others. Moreover, when choosing to buy or not buy organic food, this decision itself has been found to be rather complex, with somewhat inconsistent research results. Previous research in consumer behavior has also tried to explain the low purchase frequency of organic foods when consumers hold positive attitudes about organic food suggest that high price [17] and limited availability [6] are said to be common reasons. However, this explanation seems not give the full perspective since previous studies have shown that consumers are willing to pay more for organic products [7]. The complexities around the organic consumer and his decision are obvious - holding positive attitudes towards green consumption is not a reliable predictor if a person decides to purchase organic food or not.Consumer post-purchase behaviors have been examined in a number of ways in several different settings trying to explain the cognitive processes behind the behavior and which factors that trigger this specific behavior, but still there are few recent studies in the area. A common post purchase behavior is Cognitive Dissonance explained as a person’s behavior conflict with one’s attitudes, and consequently, an immediate pressure to reduce it [4]. Factors shaping this cognitive dissonance have been an interesting discussion, where both internal and external elements seem to affect this phenomenon. Values, attitudes, emotions and intention are some of the internal factors that consumers rely on when cognitive dissonance occur [20-24]. In turn these internal factors will also form the consumers’ intention and consequently, their behavior [1]. Previous research of post-purchase behavior has focused on high involvement products [25, 28, 29], while low involvement purchase, such as grocery shopping, has been ignored. As the author believes the instance would benefit from being studied with the theory of cognitive dissonance as a consideration. Studies examining the processes underlying expensive investments such as buying a car or a computer show that cognitive dissonance occur easily after the purchase and could be explained by a higher motivational level due to high involvement [3], or emotions [5]. Post-purchase evaluations include several factors shaping consumer behavior. In this paper the author presents a number of these factors that she think dominate the consumer thinking and cognitive processes before, during and after the actual purchase situation. This study examines if low involvement shopping context with non-organic and organic groceries also can trigger cognitive dissonance to occur in the same way as high involvement shopping. Festinger’s theory [4] adds a deepened understanding of the complexities concerning the organic consumer and that the following research could extend the knowledge of the cognitive processes of cognitive dissonance as well as contributing with more insights in the consumer behavior research area.

1.1. Purpose

- The purpose of the study is to examine consumer behavior from a cognitive dissonance perspective. The present study contains an experiment with the purpose to investigate if the choice between organic and non-organic groceries could lead to cognitive dissonance for the consumer.

2. Method

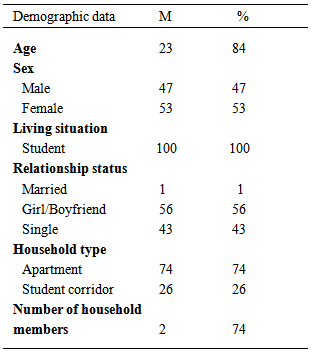

- Participants. Hundred male and female undergraduate students at a Swedish university (mean = 23 years with SD = 2.57) served as participants and were tested individually performing a virtual shopping spree. The test was voluntary and took 20 minutes to complete. The participants did not receive any compensation for participating in the study (see Table 1 for detailed demographic information).

|

|

3. Results

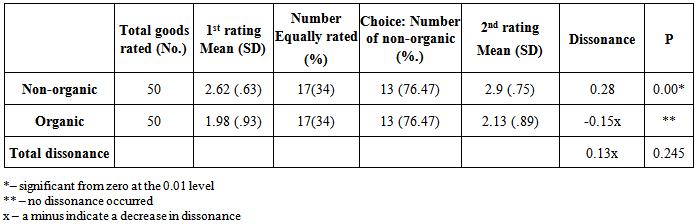

- The study consisted of a virtual simplified shopping experience where participants had to rate two goods considered equally attractive, choose one of them, and rate again (see Table 3 for detailed information about the item attractiveness rating and consumer choice). The findings of the test showed an attempt to dissonance reduction.

3.1. Rating Changes – chosen Good

- The data in Table 2 shows consumer’s ratings of non-organic products before and after the choice was made. The result reveals significant score changes for the non-organic item after it has been chosen. With a mean score of 2.62 before the item was chosen and a mean score of 2.9 after the choice was made, the total rating change is 0.28. To find if mean difference between the two samples are statistically significant, a one sample t-test was used. Comparing the two means for the ratings of the non-organic products, a one sample t-test gave the following result with t (117) = 4.18, p = .00. This indicates that the difference between the increase scored when comparing the initial rating and the second rating after the choice, is significant from zero.

3.2. Rating Changes – unchosen Item

- Reduction of dissonance could also occur through making the unchosen alternative less desirable. Here, the first rating gave the mean score 1.98 and the second rating with a mean score of 2.13. For reduction of dissonance, the score should have been lowered in the second rating. Therefore, no tendencies for dissonance reduction could be found in ratings of the organic products when choosing the non-organic option (t (110) = -2.038, p = .05).

3.3. Total Dissonance

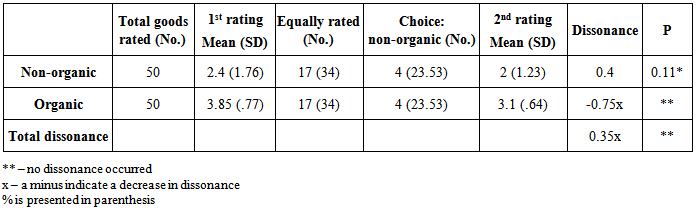

- Reduction of dissonance could also be made through increasing the desirability of chosen item, and lowering the desirability of the rejected item. Adding the two together, the results show tendencies for dissonance reduction, but the result is not significant from 0 (t (112) = 1.177, p = .25). To diminish the possibility that the results only occurred by chance, the corresponding data was collected when the organic object was chosen. The data in this study shows a slight tendency for dissonance reduction when rating the non-organic option, but the results are not significant from 0. The total dissonance showed no results, same as for the rating of the organic option. The insignificancy of the results might be explained by the low frequency of the organic option chosen, which was only chosen 4 of 17 times on average (see Table 3).

3.4. Explanation of Choice

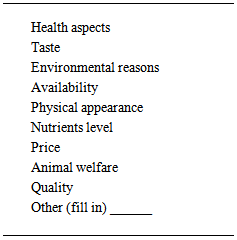

- When participants went through their second rating, the items were presented with a list of motives why the particular choice was made. The participants were asked to give their reasons from a list of ten alternatives why they chose the item they did, and why they rejected the other item. 61% of the participants that chose the non-organic product explained their choice with “Price”. Price should be understood as being the more affordable option when choosing the non-organic item, with the opposite truth for the organic option. Another recurring explanation was “Physical appearance”, which was given as a reason in 23% in all cases when choosing the non-organic option. Either, participant gave the reason meaning that they recognized the product, or because they thought the physical appearance of the non-organic product was more appealing. The ambiguity will be treated further in the discussion. When participants chose the organic product, the reason given was “Because of environmental concern” (41%) and “Animal welfare” (35%). The other motives were only chosen by less than 5% of the participants and will therefore not be discussed further.

3.5. Value Orientation

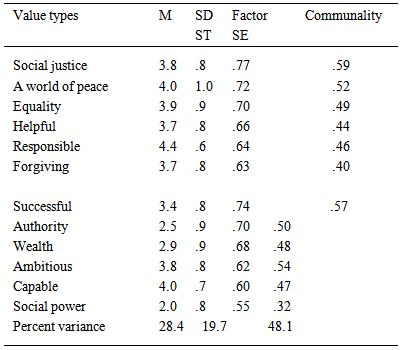

- To measure the level of social responsibility one has to look at the score for those questions belonging to the cluster of self-transcendence in the value orientation. A high score indicates a society-directed behavior closely linked to holding positive attitudes towards organic food. The population mean for self-transcendence, with data collected from 20 countries, is 3.9 [8]. This anticipates that individuals scoring 3.9 or higher must be considered more socially responsible than average. Participants in this study had a mean score of 4.0. With a one sample t-test, it could be stated that the mean differences are significant (t (114) = 32.11, p = .00). The high self-transcendence score indicates that the participants in this study are more environmentally concerned than the mean population. Self-transcendence score and comparison of population means was adapted from [22]. The results also showed no correlations between the frequency of buying organic items and value orientation self –transcendent, r = .256, p = .16, either no correlations for the frequency of buying non-organic items and value orientation self-enhancement r = .178, p = .29 (see Table 4).

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The aim of this study was to examine why, despite positive attitudes towards low involvement purchase of organic food, consumers do not purchase organic food to a high extent. The study examined how the psychological state cognitive dissonance could affect consumers’ decision making of organic food. The predictions were based on a theory by Festinger [4] and a complementing value orientation questionnaire adopted from Schwartz [22] was used to give information about the participants’ attitudes as a background variable to be able to compare a possible discrepancy between attitudes and behavior. The findings of this study suggests that an individuals’ ability to rationalize one's decision by reducing the unpleasant arousal cognitive dissonance, makes it attainable for consumers to keep repeating making decisions even when there is an obvious discrepancy between their beliefs and behavior. The purpose of the study was to investigate if the choice between organic and non-organic groceries could lead to cognitive dissonance for the consumer. The findings confirm that consumers do have a tendency to selectively attend to and process information in a way that justifies past behaviors [27], which here was done through increasing preference for chosen items. The participants in the study attend and process information carefully. This contradicts to previous research arguing that low involvement purchases are driven by habits and unconscious thinking [14, 13, 18]. In present study the change in preference before and after a choice was made was measured. In previous studies, this method has mainly been used to measure the level of dissonance arising from a choice versus rejection situation [2]. However, when examining consumers decision making towards organic food, there are several complexities one need to confront, for example the inconsistency of a positive attitude towards organic food and a contradicting behavior. It has been found that people hold positive attitudes towards organic food. Hence, this does not reflect the actual buying frequency. Considering it is very unpleasant to make decisions that is not in line with one's attitudes, one has to find ways to rationalize these decisions. If people were not able to rationalize one's decision, it would be highly unimaginable that people would continue taking such decisions. This rationalization makes the decision congruent and therefore the dissonance will be reduced and maybe even absent. This assumption does not require that there has to be two options to choose from, hence, the attitude and behavior is more than sufficient to create a state of dissonance. This finding also indicates that it is not the level of involvement that is the dominating factor triggering cognitive dissonance, rather the actual appearance of dissonance. In this study the participant had to choose between two alternatives of the same product: one organic and one non-organic that the consumer purchased to the same extent. The study showed, similar to earlier research, a significant preference change for chosen goods. When rating the chosen nonorganic product a second time, the participant gave a higher rating which indicates that after the product was chosen the participant considered the object more attractive. This preference change might have been facilitated by two things: First, the participant was reminded of if s/he chose or rejected the item, second, the participant was given a list with reasons depicting possible motives why he chose that particular product. This could be explained as follows; before the decision was made, the participant had an opinion about the product and in this study the opinion was equal to purchase frequency. It is, according to dissonance theory, inconvenient to make a decision when a preferred item has to be rejected for another preferred item [4]. For a consumer to feel satisfied with ones´ decision, a strengthening process favoring the decision made will occur and the feeling of satisfaction is enhanced – in other words the process of cognitive dissonance takes place. In the same way as a car buyer rationalizes his decision after it has been made, a consumer of nonorganic food rationalizes his decision to make it acceptable. It is also true that after a decision is made, people tend to seek information congruent with one's decision. Food shopping is considered a low involvement behavior [26] and therefore consumers most often do not take up different options for evaluation. In other words, consumers do not even consider other brands before buying. Instead, their well-established consumptions routines will make the choice for them. This habitually behavior is from a psychological perspective called cognitive scripts. A cognitive script, also called a schemata, could be likened with a manuscript of different behaviors that helps us behave and navigate in our daily life. Through the use of schemata, most everyday situations do not require effortful processing, instead automatic processing is all that is needed. [13] is convinced that most human behavior falls into automatic processing patterns because that it is the most convenient for us and that it would be impossible to consider every decision we make every day. Because of this “autopilot” that activates when consumers make everyday decisions, the uptake of new information is hampered. For the consumer, the easiest way to reach a decision while grocery shopping is to give in for automatic processing and choose the option that looks familiar. That requires almost no effort for the consumer. Given that is true, applying cognitive dissonance theory could give an extra dimension to what is known about schemata, which could at least partly explain why consumers keep taking the same decisions without evaluating the options. These results could explain the fundamental acts by consumers and explain how it is possible for consumer’s to keep repeating the same contradicting decisions.In the study the value orientation of the respondents examining if consumer value orientation could be a predictor for the buying behavior of organic food was also measured. The results showed that the respondents rated their value orientation towards a strong self-transcendent behavior. Thus, this self-transcendence could not be found in a higher extent of buying organic grocery items.

5. Conclusions

- The findings in the study indicate that the interpretation of differences in consumer behavior according to the high and low involvement as it has been explained before is too frugal, and the line between what is known as high and low involvement not as clear today as it once originally was both for which cognitive processes that is dominated in a specific purchase situation with specific characteristics but also the complexity of the definition of involvement itself when situational factors seem to have an impact on the decision and the post-purchase behavior of the consumer which could be related to the situational factors by [19]. In summary the results showed no total dissonance which could be explained by the low frequency of the organic option chosen. Price and physical appearance were explained as reasons when choosing the non-organic item, while animal welfare was pointed out as the reason when choosing the organic item. Overall, the results showed high value orientation ratings. Further, the findings suggests that an individuals’ ability to rationalize one's decision by reducing the unpleasant arousal cognitive dissonance. The confirmation of a consumers’ decision can therefore be an efficient way to affect consumer purchase both during the actual purchase but in particular it could facilitate for future purchases the consumer will make. By keeping the unpleasant feeling of cognitive dissonance makes an excellent opportunity for marketers and retailers to affect the consumer to make the choice they want the consumer to make.An interpretation of the high score of self-transcendence could be that consumers separate their actions of different areas and these actions are also valuated differently. Recycling at home does not mean that you have a strong belief to do it at work, or buying non-organic food does not mean that you never buy environmental friendly products such as clothes or electronic equipment. This could imply that consumers base their self-transcendence from one area that they rate as important to them and ignore other areas such as level of buying organic goods in their grocery shopping into this account. According to Lerner, Stern and Lowenstein [15] the results maybe indicate that decisions are influenced by the ambient emotion the consumer happen to be feeling in the purchase decision that Schwartz [22] means lie outside the content of their beliefs.

6. Limitations

- Due to the limitations of this study, changes of preferences when a consumer chooses the organic option should be further examined. Also, because of the well-known complexities around the organic consumer, the author suggests that an in-store experimental study could contribute to increase the knowledge of the organic consumer’s decision making and other low involvement decisions made by consumers. Even if real life experiments in the laboratory is useful and showing the appearance of the fundamental basic cognitive processes, real world shopping spree could deepen the actual fluctuating consumer behavior in a wider range of measures, such as heart rate and eye tracking.

References

| [1] | Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. |

| [2] | Brehm, J. (1956). Post-decision changes in desirability of alternatives. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52, 384–389. |

| [3] | Elliot, A. J., & Devine, P. G. (1994). On the Motivational Nature of Cognitive Dissonance: Dissonance as Psychological Discomfort. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 382-394. |

| [4] | Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press. |

| [5] | Fontanari, J.F. (2011). Emotions of cognitive dissonance. International Conference on Neural Networks, 95-102. |

| [6] | Fotopoulos, C., & Krystallis, A. (2002). Organic product avoidance: Reasons for rejection and potential buyers’ identification in a countrywide survey. British Food Journal, 104, 233–260. |

| [7] | Gil, J. M., Gracia, A., & Sánchez, M. (2000). Market segmentation and willingness to pay for organic products in Spain. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 3, 207–226. |

| [8] | aHansla, A., Gamble, A., Juliusson, E. A., & Gärling, T. (2008). Psychological determinants of attitude towards and willingness to pay for green electricity. Energy Policy, 36, 768-774. |

| [9] | bHansla, A., Gamble, A., Juliusson, E. A., & Gärling, T. (2008). The relationship between awareness of consequences, environmental concern, and value orientations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28, 1-9. |

| [10] | Hughner, R. S., McDonagh, P., Prothero, A. (2007). Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 6, 94-110. |

| [11] | Izuma K., Matsumoto, M., Murayama, K., Samejima, K., Sadato, N., & Matsumoto, K. (2010) Neural correlates of cognitive dissonance and choice-induced preference change. National Academy of Science USA, 107, 22014 –22019. |

| [12] | Jaeschke, R., Singer, J., Guyatt, GH. (1990). A comparison of seven-point and visual analogue scales. Data from a randomized trial. Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, 11, 43-51. |

| [13] | Jarcho, J. M., Berkman, E. T., & Lieberman, M. D. (2011). The neural basis of rationalization: cognitive dissonance reduction during decision-making. Social Cognition Affect Neuroscience, 6, 460-467. |

| [14] | Krugman, H. E. (1977). Memory Without Recall, Exposure Without Perception. Journal of Advertising Research, 17, 7-12. |

| [15] | Lerner, J. S., Small, D. A., & Loewenstein, G. (2004). Heart strings and purse strings: Carry- over effects of emotions on economic transactions. Psychological Science, 15, 337-341. |

| [16] | Losasso, C., Cibin, V., Cappa, V., Roccato, A., Vanzo, A., Andrighetto, I., & Ricci, I. (2012). Food safety and nutrition: Improving consumer behavior. Food Control, 26, 252-25. |

| [17] | Padel, S., & Foster, C. (2005). Exploring the gap between attitudes and behavior: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. British Food Journal, 107, 606–625. |

| [18] | Ray, M. L., A. G., Sawyer, M. L., Rothschild, R. M., Heeler, E. C., Strong, & Reed, J. B. (1973). Marketing Communication and the Hierarchy of Effects in P. Clarke ed., New Models for Mass Communication Research. Beverly Hills; Sage. |

| [19] | Reutterer, T., & Teller, C. (2009), Store format choice and shopping trip types. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37, 695 – 710. |

| [20] | Rohan, M.J. (2000). A rose by any name? The values construct. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 255-277. |

| [21] | Schultz, P.W., Gouveia, V.V., Cameron, L.D., Tankha, G., Schmuck, P. & Franek, M. (2005) Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 457-475. |

| [22] | Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. InM. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. |

| [23] | Stern, P.C. & Dietz, T. (1994). The Value Basis of Environmental Concern. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 65-84. |

| [24] | Stern, P.C., Dietz, T., & Kalof, L. (1993). Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environment and Behavior, 25(3), 322-348. |

| [25] | Sweeney, J. C, Hausknecht, D., & Soutar, G. N. (2000). Cognitive dissonance after purchase; A multidimensional scale. Psychology and Marketing, 17, 369-385. |

| [26] | Tarkiainen, A., Sundqvist, S. (2005). Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. British Food Journal, 107, 808-822. |

| [27] | Thørgersen, J., (2011) Green Shopping: For Selfish Reasons or the Common Good?. American Behavioral Scientist 55, 1052-1076. |

| [28] | Voss, G. B., Parasuraman, A., & Grewal, D (1998). The Roles of Price, Performance, and Expectations in Determining Satisfaction in Service Exchanges Author(s). Journal of Marketing, 62, 46-61. |

| [29] | Zaichowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 341-352. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML