-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(3): 98-105

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140403.03

Fostering Desirable Behaviour among Secondary School Adolescents with Emotional and Behavioural Disorders (EBD); -The Contributions of Positive Behavioural Intervention

Afusat Olanike Busari

Department of Guidance & Counselling, Faculty of Education, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Afusat Olanike Busari, Department of Guidance & Counselling, Faculty of Education, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study investigated Positive Behavioural Support (PBS) intervention in fostering desirable behaviour among secondary school adolescents with emotional and behavioural disorders. Eighty (80) adolescents male and female selected through multi- stage sampling techniques participated in this study. Pre- Post- test quasi –experimental design was adopted for this study. Two research instruments were used as assessment measures in this study. Behavioural Assessment System for Children (BASC) was used for screening while Behavioural and Emotional Screening System (BESS) (Kamphaws & Reynolds, 2007) was used for data collection. Four research hypotheses guided this study at 0. 05 level of significant. The results of the findings indicate that there existed significant main effect of treatment on participants’ emotional and behavioural disorders.

Keywords: Positive Behavioural Support, Fostering, Desirable Behaviour, Adolescent, Emotional Behavioural Disorder

Cite this paper: Afusat Olanike Busari, Fostering Desirable Behaviour among Secondary School Adolescents with Emotional and Behavioural Disorders (EBD); -The Contributions of Positive Behavioural Intervention, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 98-105. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140403.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The term emotional and behavioural disorder (EBD) encompasses a wide variety of behaviours and characteristics. Students with EBD often exhibit behaviours that interfere with academic success in schools. Like other students with disabilities, they also experience difficulties learning in various content areas, such as reading and math. Many of these students have difficulty maintaining appropriate social relationships with peers and adults. Some of these students exhibit noncompliant behavior, aggression, and disrespect toward authority figures. Due to these challenging behaviours, they experience unfortunate predicaments, such as misidentification, marginalization from access to education, and exclusion from general education environments. Schools are the largest providers of emotional, behavioral, and educational supports for children and adolescents. More students in the school-aged population exhibit emotional, behavioral, and mental health issues necessitating supports and interventions than those who actually receive it. Recent reviews of research suggest that students with EBD need early interventions and ongoing supports for positive outcomes in their lives (Bradley, et al. 2004; Landrum, et al. 2003). EBD coexists with multiple identifiable conditions (depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder) that require comprehensive care, which is not consistently available to many of these students. Studies have examined the importance of early intervention programs for children with EBD and have found that these programs benefit these children (Egger & Angold, 2006; Kauffman, et al, 2007; Wagner, et al, 2005). Highlights that one-third (31 percent) of all children with EBD are served in more restrictive settings. When compared to students from other disability categories, that percentage is significantly higher than the average. Reviewed research on behavioral and emotional psychiatric disorders in preschool children (children ages two through five years old), and focused on the five most common groups of childhood psychiatric disorders: attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, oppositional defiant and conduct disorders, anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders. Lane, Carter, Pierson, and Glaeser, (2006) Identifies three broad intervention areas of inappropriate behaviours, academic learning problems, and interpersonal relationships. The authors argue for specialized interventions for students with EBD because of their unique needs. Students who are at risk for EBD have difficulty with learning, social relationships, depression, and anxiety and exhibit inappropriate behaviors. School administrators tend to be aware of those students because they usually require a great deal of support and a variety of resources to appropriately participate in school.Early identification of students who are at risk helps school teams provide timely intervention and support to address problem behaviors before they become entrenched and difficult, if not impossible, to manage(Kauffman, et al, 2007). Although students who are at risk for EBD may display only some of the core characteristics and with less frequency or intensity than those who are actually identified as having EBD, early identification and intervention can lead to improved educational outcomes.

2. Characteristics of Students with EBD

- Social alienation for students is highly related to anxiety, depression, and conduct problems, and students who are at risk for EBD may be seen as lonely, unlikable, provoking, and lacking in social competency. These negative characteristics and outcomes may be avoided or minimized with early identification and intervention.

2.1. Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviours

- EBD is often identified in internalizing or externalizing categories. Internalizing behaviors are associated with problematic internal feelings, such as anxiety, sadness, reticence, fearfulness, and over sensitivity. Students with externalizing behaviors tend to show outward behavioral problems that include aggression, unruliness, forcefulness, and oppositional behaviors. A few students may display both internalizing and externalizing behaviors (student with aggressive behaviors who also displays some depressive or anxious feelings), but usually students can be identified as primarily externalizing or internalizing.Screening for both internalizing and externalizing behaviours is important because students with internalizing problems are easily overlooked: they typically create few discipline problems and maintain good grades, although some may have attendance problems. Teachers who are aware of students who are withdrawn, anxious, fearful, and unassertive can help school teams identify them so that early interventions can be put in place.Students with externalizing tendencies are more readily noticed by teachers. Such behaviors as getting out of one’s seat, provoking peers, acting aggressively, and refusing to stay on task occur frequently in students with EBD, and those behaviours often require the teacher’s attention or disciplinary actions. Students with EBD tend to have high numbers of office referrals for behavioral offenses. Students who commit one to three behavioural offenses in sixth grade are more likely to have continued behaviour problems in eighth grade and are less likely to be on track for high school graduation (Tobin & Sugai, 1999).Students with EBD also have low attendance at school, which would contribute to poor academic performance, but attempting to help them learn through grade retention is ineffective (Anderson, Kutash, & Duchnowski, 2001). Because students with EBD have difficulties with academics, screening helps identify those who are at risk so that they can receive focused help, rather than simply be retained.

2.2. Gender Issues

- Most students identified as at risk for or as having EBD are male. Surprisingly this prevalence occurs in both the external and internal categories, although male students are more likely to display external behaviours than internal ones. This may be seen when adolescent males express depressive feelings externally through negative interpersonal interactions. Females are identified as being at risk less frequently, but when they are identified, they are more commonly identified as internalizers. Because males are much more likely to be identified as EBD or as at risk for EBD, teachers and administrators must be sure that they are not overlooking the needs and behaviours of adolescent females in the screening process (Young, Sabbah, Young, Reiser, & Rich-ardson, 2010).Adolescent males express depressive feelings externally through negative interpersonal interactions. Females are identified as being at risk less frequently, but when they are identified, they are more commonly identified as internalizers. Because males are much more likely to be identified as EBD or as at risk for EBD, teachers and administrators must be sure that they are not overlooking the needs and behaviours of adolescent females in the screening process (Young, Sabbah, Young, Reiser, & Rich-ardson, 2010).

2.3. Environmental Factors

- Teachers often notice environmental factors. When students appear hungry or tired, teachers may view them as being at risk. In addition, teachers notice students who appear to have less-involved parents or familial stress. One group of researchers determined that nontraditional family structure, low socioeconomic status, multiple school changes, urban school atmosphere, and parental dissatisfaction with the school were all predictors of school exclusion (expulsions and suspensions) for students with EBD (Achilles, McLaughlin, & Croninger, 2007). Those findings suggest that heightened EBD indicators as measured by school exclusion may be influenced by a student’s environment. Quality of life issues or other environmental factors may influence the manifestation of EBD. When students completed a quality of life survey, those identified as having EBD demonstrated lower feelings of self -competence and reported negative relationships with others. These quality of life scores did not differ significantly across ages or between the sexes of students with EBD (Sacks & Kern, 2008). By considering the aspects of a student’s environment, a school team may increase its ability to intervene early and help support a young person who is at risk before he or she develops maladaptive behavioral patterns that are resistant to interventions.

2.4. Screening Processes

- Screening processes should be efficient, practical, evidence based, and effective. Unfortunately, few have been specifically designed to identify at-risk secondary students with either externalizing or internalizing behaviors. Some recent research efforts (Caldarella, Young, Richardson, Young, & Young, 2008; Young et al., 2010) have used a teacher nomination process to identify at-risk students. Those researchers used the teacher nomination form to generate a list of students about whom teachers expressed concern, then followed up with assessments to better identify student needs. Screening in secondary schools can be a valuable process for identifying students before problems become so troublesome that many resources are needed to intervene. Students who are troubled with emotional and behavioral concerns can easily fall through the cracks, and then school teams must scramble to identify needs and find the means to support those students who eventually slide into crisis. Providing services in a timely manner helps prevent crises from developing so that students can be successful.

2.5. Positive Behaviour Support Intervention

- Positive behavior support is a form of applied behavior analysis (ABA) that uses a system to understand what maintains an individual's challenging behaviour. People's inappropriate behaviours are difficult to change because they are functional; they serve a purpose for them. These behaviours are supported by reinforcement in the environment. In the case of students and children, often adults in a child’s environment will reinforce his or her undesirable behaviours because the child will receive objects and/or attention because of his behaviour. Functional behaviour assessments (FBAs) clearly describe behaviours, identifies the contexts (events, times, and situation) that predict when behaviour will and will not occur, and identifies consequences that maintain the behaviour. It also summarizes and creates a hypothesis about the behaviour, and directly observes the behaviour and takes data to get a baseline. The positive behaviour support process involves goal identification, information gathering, hypothesis development, support plan design, implementation and monitoring (Kamphaus & Reynolds 2007).By changing stimulus and reinforcement in the environment and teaching the child to strengthen deficit skill areas the student's behavior changes in ways that allow him/her to be included in the general education setting. The three areas of deficit skills identified in the article were communication skills, social skills, and self-management skills. Re-directive therapy as positive behaviour support is especially effective in the parent–child relationship. Where other treatment plans have failed re-directive therapy allows for a positive interaction between parents and children. Positive behaviour support is successful in the school setting because it is primarily a teaching method (Swartz, 1999). Schools are required to conduct functional behavioural assessment (FBA) and use positive behaviour support with students who are identified as disabled and are at risk for expulsion, alternative school placement, or more than 10 days of suspension. Even though FBA is required under limited circumstances it is good professional practice to use a problem-solving approach to managing problem behaviours in the school setting (Crone & Horner 2003).The use of Positive Behaviour Intervention Supports (PBIS) in schools is widespread (Sugai & Horner, 2002). A basic tenet of the PBIS approach includes identifying students in one of three categories based on risk for behaviour problems. Once identified, students receive services in one of three categories: primary, secondary, or tertiary. To help practitioners with differences in interventions used at each of the levels the professional literature refers to a three-tiered (levels) model (Stewart, Martella, Marchand-Martella, & Benner, 2005; Sugai, Sprague, Horner & Walker, 2000; Tobin & Sugai, 2005; Walker et al., 1996.) Interventions are specifically developed for each of these levels with the goal of reducing the risk for academic or social failure. These interventions may be behavioural and or academic interventions incorporating scientifically proven forms of instruction such as direct instruction. The interventions become more focused and complex as one examines the strategies used at each level.Functional behavior assessment (FBA) emerged from applied behavior analysis. It is the first step in individual and cornerstone of a Positive Behaviour Support plan. The assessment seeks to describe the behaviour and environmental factors and setting events that predict the behaviour in order to guide the development of effective support plans.There are many different behavioral strategies that PBS can use to encourage individuals to change their behaviour. Some of these strategies are delivered through the consultation process to teachers. The strong part of functional behaviour assessment is that it allows interventions to directly address the function (purpose) of a problem behaviour. For example, a child who acts out for attention could receive attention for alternative behaviour (contingency management) or the teacher could make an effort to increase the amount of attention throughout the day (satiation). Changes in setting events or antecedents are often preferred by PBS because contingency management often takes more effort (Rhodes, Stevens & Hemmings, 2011). Another tactic especially when dealing with disruptive behaviour is to use information from a behaviour chain analysis to disrupt the behavioural problem early in the sequence to prevent disruption. Some of the most commonly used approaches are:The main keys to developing a behavior management programme include:Identifying the specific behaviours to addressEstablishing the goal for change and the steps required to achieve itProcedures for recognizing and monitoring changed behaviourThrough the use of effective behaviour management at a school-wide level, PBS programmes offer an effective method to reduce school crime and violence. To prevent the most severe forms of problem behaviours, normal social behaviour in these programmes should be actively taught (Hawken & Johnston 2008).The current trend of positive behavior support (PBS) is to use behavioral techniques to achieve cognitive goals. The use of cognitive ideas becomes more apparent when PBS is used on a school-wide setting. A measurable goal for a school may be to reduce the level of violence, but a main goal might be to create a healthy, respectful, and safe learning, and teaching, environment (Scott, Gagnon &Nelson, 2008) . PBS on a school-wide level is a system that can be used to create the "perfect" school, or at the very least a better school, particularly because before implementation it is necessary to develop a vision for what the school environment should look like in the future (Sacks & Kern, 2008).According to Horner et al. (2004), as cited in (Miller, Nickerson, & Jimerson, 2009) once a school decides to implement PBS, the following characteristics require addressing:Define 3 to 5 school-wide expectations for appropriate behavior;Actively teach the school-wide behavioural expectations to all students;Monitor and acknowledge students for engaging in behavioural expectations;Correct problem behaviours using a consistently administered continuum of behavioural consequences;Gather and use information about student behavior to evaluate and guide decision making;Procure district-level support of adequate support and consistency using a positive behavior support program exists, then over time a school’s atmosphere will change for the better. PBS is capable of creating positive changes so glaring that people will notice the differences upon a visit to the school. Such a program is able to create a positive atmosphere and culture in almost any school, but the support, resources, and consistency in using the program overtime must be present(Achilles, McLaughlin & Croninger, 2007).School-wide Positive behavior support (SW-PBS) consists of a broad range of systematic and individualized strategies for achieving important social and learning outcomes while preventing problem behavior with all students.

2.6. Purpose of Study

- This study seeks to identify probable effects of Positive Behavioural Support Intervention (PBS) in fostering desirable behaviours among secondary school adolescents with emotional and behaviour disorders. In the process of the research however, the study will examine whether gender and type of school attended can prove any significant effect on the participant’s level of emotional and behavioural disorders after the treatment.

2.7. Research Hypotheses

- The following null hypotheses were formulated and tested at 0.05 level of significant to guide the study:-H₀1 There will be no significant main effect of treatment on emotional and behavioural disorders among secondary school adolescents.H₀2 There will be no significant main effect of type of school on emotional and behavioural disorders among secondary school adolescents.H₀3 There will be no significant main effect of gender on emotional and behavioural disorders among secondary school adolescents.H₀4 There will be no significant interaction effect of treatment and parent’s level of education on emotional and behavioural disorders among secondary school adolescents.

3. Design

- The study employs a pre-post -test quasi experimental design, using 2×2×2 factorial matrix. The two refers to the treatment which comprises one experimental group and the control group. The treatment and the control group makes up the row. The first major column consists of the gender of the participants varying at two levels of male and female while the other major column connotes the type of school separated into private and public.

3.1. Sample and Sampling Techniques

- The sampling techniques adopted for this study was a multi- stage type. First, two Local Government Areas were randomly selected from Ibadan Metropolis. Again four secondary schools, two schools each from the selected Local Government areas were selected through random sampling techniques. The participants of this study were screened using Behavioural Assessment System for Children (BASC). It was thus used to identify the adolescents with high level of emotional and behavioural disorders. While Behavioura l and Emotional Screening System (BESS, Kamphaus & Reynolds, 2007) was used as pre-test measure for the 80 finally selected participants of this study. Forty participants each from the two schools with high scores in Behavioural Assessment System for children (BASC) constitute the participants of this study. Out of the participants 52 (65%) were males while 28(35%) were females. The participants from the private schools were 24 (30%) and those from public schools 56(70%). For the participants parents’ level of education 48(60%) were literates while 32 (40%) were illiterates. The participants of this study were senior secondary school students (SSII) in their second year.

3.2. Research Instrument

- Two research instruments were used in this study. Behavioural Assessment System for Children (BASC) was used for screening while Behavioural and Emotional Screening System (BESS) (Kamphaws & Reynolds, 2007) was used for data collection. Behavioural and Emotional Screening System (BESS) is a 30 items questionnaire which has two sections. Section A of BESS consists of demographic data such as age, sex, school etc. while Section B consists of 30-items eliciting information on the severity of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders (EBD) symptoms within different categories of concern. BESS is a five point likert rating scale with anchors such as 5= very much like me, 4= like me, 3= not sure, 2= unlike me, and 1= very much unlike me. The highest possible score is 150 and the lowest possible score is 30. Scores between 110 and 150 indicates severe level of EBD and as such individuals in this category are regarded at risk as confirmed by BESS. The reliability of the instrument was established on SS two students different from the participants of the study and a coefficient reliability of 0.88 was obtained after two weeks interval of test- retest.

3.3. Procedure

- Permission was sought from the principals of the two secondary schools of study, before the intended selection test and the actual training programme. Thus the official consent and approval was obtained for the programme. Session 1:- The treatment programme commenced with the introduction of participants to each other and introduction of therapists to the participants. The participants were informed that the treatment programme will cover a period of 12weeks of 1hour per session in a week. The experimental sessions started with the preamble and orientation for the participants, which includes the introductory talk to establish rapport and enabling environment for the programme. The objectives of the programme and the benefits to be derived by the participants were also discussed. The therapists also sought for the co-operation of the participants. The pre-test measure was then administered to the participants.Session 2:- During this session, the participants were taught the meaning and concept of Positive Behavioural Intervention Supports as a form of applied behaviour analysis that uses system to understand what maintains an individual’s challenging behaviours. They were taught that the positive behaviour support process involves goal identification, information gathering, support plan design, implementation and monitory.Session 3:- Here participants were asked to describe their problem behaviours and its general setting of occurrence. Again they were asked to identify events, times and situations that predict their problem behaviours. Participants were also asked to write down consequences maintaining their behaviours, Among the problem behaviours described and identified are:- aggression, vandalism, truancy, bullying, mob-disobedience, improper dressing and deficient communication.Session 4:- This session witnessed the discussion of communication skills which was one of deficits identified in the previous session. The concept of communication was discussed with the participants. Characteristics and how communication could be used effectively to avert behaviour problems was also explained to them.Session 5:- Social skills training was the focus of this session. Primarily cognitive- behavioural approach was used to teach social skills to the participants. The participants were taught that social skills training is a form of behaviour therapy used by teachers, therapists, and trainers to help persons who have difficulties relating to other people. Some of things taught the participants are:-● Participants were taught to learn to interpret social signals, so that they can determine how to act appropriately in the company of other people in variety of different situations.● They were taught how to improve their social skills or change selected behaviours in order to raise their self-esteem and increase the likelihood that others will respond favourably to them.● They also learnt how to change their social behaviour patterns by practicing selected behaviours as individuals or in group sessions.● They were taught how to improve their abilities to function in everyday social situations.● They were imbued with social skills to enable them mingle with others and to acquire greater skills in self- confidence.Session 6:- During this session, self-monitoring techniques was discussed with the participants. Self- monitoring techniques was explained as techniques for unlearning old behaviours. They were taught that monitoring involves paying careful and systematic attention to individual’s problems. The therapists discussed with the participants that self-monitoring deals with emotional self- regulations. It deals with the phenomena of expressive controls. The participants were informed that people concerned with their expressive self-presentation tend to closely monitor themselves in order to ensure appropriate or desired public appearances. Individual with high self- monitors often behave in a manner that is highly responsive to social cues and their situational context.Session 7:- Training in cognitive restructuring was the focus of this particular session. The participants were taught that they were affected by their negative and unrealistic thoughts. They were therefore taught how to replace these unrealistic thoughts with positive and realistic ones.Session 8:- This session witnessed identification of various root causes of emotional and behavioural disorders. The participants were taught that properly addressing the root causes of behaviour problems can prevent participants’ failure in life. Root causes identified include hereditary, improper child rearing techniques, cruelty on the part of some teachers, peer - group influence, denial of essential school needs by parents, difficult school rules etc. All these were appropriately discussed to prevent or ameliorate emotional and behavioural disorders as the case may be.Session 9:- Proactive approach to establish the behavioural supports and social culture needed for all the participants to achieve social, emotional and academic success form the basis of discussion in this session. Attention was focused on sustaining systems of support that will improve lifestyle results (personal, health, social, family, recreation) for all the participants by making targeted misbehaviour less effective, efficient, and relevant, and desirable behaviours more functional.Session 10:- During this session participants were taught variety of virtues such as obedience, friendliness, punctuality, etc. They were taught how to reinforce appropriate behaviours as they occur.Session 11:- Review of previous session was the focus of this session. Clarifications were made on previous interactions.Session 12:- Participants, role played, rehearsed, and modeled the various activities that have taken place in the earlier sessions. Post-test measure was administered to both the treatment and the control group.

3.4. Data Analysis

- Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used in analysing the data in this study so as to control for confounding variables by removing initial differences between the participants in the experimental group (Positive Behavioura Support Intervention PBS) and the control group.

4. Results

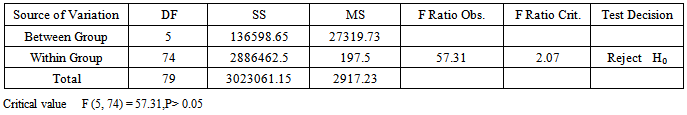

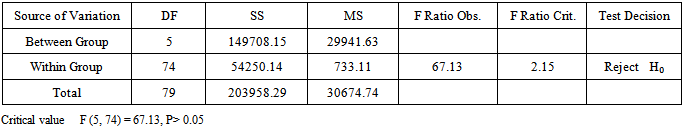

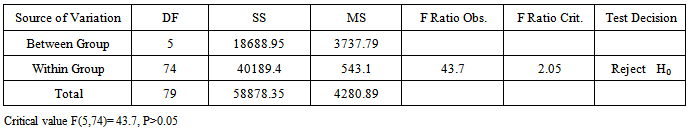

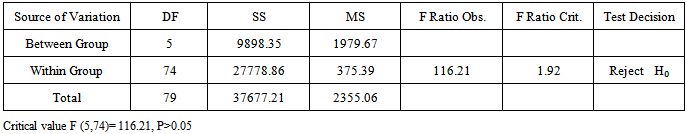

- The result as shown in table 1 indicates a significant main effect of treatment (Positive Behavioural Support Intervention) on emotional behaviour disorders among secondary school adolescents. The null hypothesis was thus rejected.As revealed in table 2, the post treatment outcome of participants based on type of school indicated significant interaction effect of treatment on participants’ emotional and behavioural disorders. The findings thus support the sustenance of the alternative hypothesis.The post-treatment outcome as indicated in table 3 showed that there existed main significant effect of treatment (Positive Behavioural Support Intervention) on participants’ level of emotional and behavioural disorders. The null hypothesis was therefore not supported.The compared outcome of pre and post treatment revealed that, there was a significant main effect (Positive Behavioural Support Intervention) on participants’ level of emotional and behavioural disorders based on gender.

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- The results obtained from hypothesis one revealed that there existed significant main effect of treatment on participants’ emotional and behavioural disorders. This result confirmed the importance of independent variables in exerting influence on criterion variables. The present study supports that of Swartz, (1999) who found that positive behavioural support is successful in the school setting because it is primarily a teaching method. The results of findings of this study is not unexpected taking into account the fact that the therapists taught the participants actively different and varieties of skills such as social skills, communication skills, and self-management skills to re-direct their emotional and behavioural deficits.The second hypothesis which stated that there will be no significant main effect of the type of school on emotional and behavioural disorders of the participants was rejected. The results as obtained from the findings indicated significant main effect of treatment on the participants based on the type of school they are attending (private or public). This study corroborates the findings of Egger & Angold (2006) that environment is an important factor in deciding occurrence of disruptive behaviour. It is therefore expected that the effectiveness of treatment will depend on the environmental maintenance of such behaviours. The result of the third hypothesis indicates that there was significant main effect of treatment on the participants based on their parents level of education .The finding is in support of the assertion of Kauffman et al (2007) which explained that early identification of students who are at risk helps school teams provide timely intervention and support to address problem behaviors before they become entrenched and difficult, if not impossible, to manage. Although students who are at risk for EBD may display only some of the core characteristics and with less frequency or intensity than those who are actually identified as having EBD, early identification and intervention can lead to improved educational outcomes. The early identification is expected of literate parents who in turn report such observation to the school authorities or the counsellor as the case may be since one of the basic tenant approach of PBIS was identification so as to be able to provide appropriate support and treatment early enough to prevent the problem from getting to uncontrollable level.From the result obtained from the fourth hypothesis significant main effect of treatment on the participants existed based on gender. The present finding is in agreement with the results obtained by Young, Sabbah, Young, Reiser, & Rich-ardson, (2010) that females are identified as being at risk less frequently, but when they are identified, they are more commonly identified as internalizers. Because males are much more likely to be identified as EBD or as at risk for EBD, teachers and administrators must be sure that they are not overlooking the needs and behaviours of adolescent females in the screening process.The main keys to developing a behaviour management programme were utilized in this study. The researcher followed religiously the process of identifying the specific behaviours to be addressed, establishing the goal for change and the steps required to achieve it, so also procedures for recognizing and monitoring changed behaviour were thoroughly adopted during the treatment programmes. Thus the success recorded in this study is not unexpected.

6. Conclusions

- The current trend of positive behavior support (PBS) is to use behavioural techniques to achieve cognitive goals. The use of cognitive ideas becomes more apparent when PBS is used on a school-wide setting. A measurable goal for a school may be to reduce the level of violence, but a main goal might be to create a healthy, respectful, and safe learning, and teaching environment. PBS on a school-wide level is a system that can be used to create the "perfect" school, or at the very least a better school, particularly because before implementation it is necessary to develop a vision for what the school environment should look like in the future.For future research, it is suggested that one-to-one talk therapy for adolescents which are both cognitive and behavioural in nature should be used to manage Emotion Behaviour Disorder. Through this, youths should be trained to “unlearn” their self-defeating attitudes and behabviours. Again, the whole family should always be treated along with the adolescent with Emotion Behaviour Disorder. Group therapy, by adolescent and led by a trained counselor provides opportunities to learn with and from one another. This group doubles as a socialization group, helping children to redefine their social skills.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML