-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(2): 57-69

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140402.01

Aggressiveness as Proximal and Distal Predictor of Risky Driving in the Context of Other Personality Traits

Laura Šeibokaitė1, Auksė Endriulaitienė2, Rasa Markšaitytė2, Kristina Žardeckaitė-Matulaitien2, Aistė Pranckevičienė2

1Theoretical Psychology Department, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, LT-44244, Lithuania

2General Psychology Department, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, LT-44244, Lithuania

Correspondence to: Laura Šeibokaitė, Theoretical Psychology Department, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, LT-44244, Lithuania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The hypothesis of aggressiveness among other personality traits being the most important factor for risky driving was tested in three different samples: more experienced drivers (N = 284), young drivers (N = 220) and drivers-learners (N = 361). Driving violations and errors were used as indicators of self-reported risky driving in the samples of experienced and young drivers; attitudes towards safe behaviour in the traffic were used as indicator of self-reported risky driving in the sample of drivers-learners. Personality was measured with the Big Five Inventory, the Aggressiveness scale, the Jackson or Donovan risk-taking scales and the Motor Impulsiveness subscale. Multivariate analysis revealed that aggressiveness should be viewed only as a distal predictor of road safety attitudes in a sample of drivers-learners. But in a sample of experienced drivers aggressiveness was found to be as a proximal predictor for both gender traffic rule violations and female errors while driving. For young drivers aggressiveness was an important predictor of male, but not female self-reported risky driving. Thus, on the large scale aggressiveness is one of the most important predictors of self-reported risky driving among other personality traits. The reduction of aggressive behaviour should become a priority in risky driving prevention and intervention programs.

Keywords: Aggressiveness, Personality, Experienced drivers, Young drivers, Drivers-learners, Risky driving behavior, Attitudes towards traffic safety

Cite this paper: Laura Šeibokaitė, Auksė Endriulaitienė, Rasa Markšaitytė, Kristina Žardeckaitė-Matulaitien, Aistė Pranckevičienė, Aggressiveness as Proximal and Distal Predictor of Risky Driving in the Context of Other Personality Traits, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 57-69. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140402.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Road traffic crash fatal and other injuries are a serious global concern. Death rates caused by traffic accidents in Lithuania, along with Poland and Romania, are among the highest in EU [1]. Therefore, countries like this need more evidence based interventional efforts in field of traffic safety. Authors suggest as well as accidents’ analysis show that most of vehicle accidents are caused by human factor, mainly risky driving style [2]. Many studies were aimed to evaluate the role that personality plays in the etiology of risk taking behaviour on the road [3-8]. Most frequently the personality traits measured by Five Factor Model are analysed; as well as several other traits like sensation seeking, impulsiveness, aggressiveness and risk taking propensity.

1.1. The Predictive Value of Personality Traits

- Previous studies have found that low scores of conscientiousness and agreeableness, as well as high scores of sensation seeking and impulsiveness can contribute to various risky driving behaviours, including violations, driving errors, driving while intoxicated and their outcomes [3-12]. Although many studies succeeded to find the relationship between these personality traits and driving behaviour, controversial results could be found as well. In some studies conscientiousness could not explain neither involvement into vehicle accident [8] nor aggressive driving [5]; or its value in prediction of risky driving was very weak [7]. Agreeableness failed to correlate with driving behaviour when the self-reported risky driving outcomes were analysed or more sophisticated statistical procedures were applied [8, 11]. Sensation seeking lost its predictive value for speeding when other psychological constructs, like risk assessment or imitation were taken into account [13]. No significant relationship was found between reckless driving and impulsiveness in a group of young drivers in the study conducted by Teese and Bradley [14]. Empirical data related to the importance of other Big Five personality traits is more inconclusive. Some studies revealed positive (mostly weak) correlations between neuroticism [8, 11], extraversion [3, 4, 8, 12, 15, 16], openness to experience [3, 4] and self-reported risky driving. However, many research results show no relationship between these variables, especially when more sophisticated statistical models are applied [3, 5, 7, 11, 12, 15, 16]. Some authors suggest that a risk taking propensity (or aversion to risk) should be analysed in risky driving research as several studies found it to be a significant predictor of driving behaviour [18, 19].There might be several reasons why the results in a field of risky driver’s personality are inconsistent. Reviewed studies differ significantly on assessment tools used [4] and analysed dependent variables, such as lapses, errors and violations as measured by Driver Behaviour Questionnaire, accident risk, accident involvement, and various compositions of the above. The use of simple statistics techniques like correlations or mean comparison may lead to invalid results due to interrelatedness among Big Five traits being ignored [20]. Therefore, a multivariate statistics should be used in order to determine the role of personality in risky driving and its consequences. Data have shown that personality traits have the ability to predict the risky driving pattern and the related outcomes of such behaviour. However, inconsistent results of previous research have led us to presume that this relationship may be mediated by other predictors, including other personality traits themselves. Previous research have revealed that the relationship between personality and risky driving is rather indirect, moderated by attitudes towards risk taking on the road [21-23], risk perception [24] and developmental challenges, like peer pressure for young drivers [25, 26]. Despite the indirect effect, analysing personality can be valuable because it accounts for attitudinal, perceptual variables and then for risky driving.

1.2. Aggressiveness as a Main Predictor of Risky Driving

- Among the various personality traits, this paper focuses on aggressiveness as a key predictor of risky driving. Aggression refers to any act, which has an intention to hurt others physically or psychologically, or readiness to react in a hostile way [27]. Persistence of such behaviour in provoking or even neutral situations could be referred to aggressiveness as a personality trait. It would be reasonable to believe that aggressiveness appears in driving situations as well as in many other contexts of one’s existence. There is a problem of inconsistency of terms and constructs within aggressiveness and risky driving research area. Many authors have defined driving anger either as a trait or as a state that manifests itself through aggressive driving after the occurrence of certain triggering event [28, 29]. In many driving behaviour studies, aggressive driving has been analysed as a dependent variable which describes socially inappropriate behaviours on the road as tailgating, running a red light, headlight flashing, yelling at others [29, 30]. While defining aggressive driving authors stressed aggressive nature of the behaviour. In our opinion, some of the mentioned behaviours like running a red light do not exactly reflect the definition of aggressiveness. On the other hand, one cannot conclude that inappropriate behaviour on the road does not always denote aggressive driving. Parker, Reason, Mansted, and Stradling [31] described driver’s behaviour in terms of making errors, lapses (which might indicate driving skills), and intentional violations of traffic rules (might partially reflect aggressive driving). If only aggressive driving is studied, then it remains unclear how aggressiveness that is not driving specific contributes to other driving performance indicators.Previous research revealed that aggressiveness was found to be attributed to many driving behaviours and outcomes. For example, in a traffic situation, aggressive people drive in an aggressive manner [32, 33]. Risky driving could be predicted by higher aggressiveness along with other personality traits [7, 34]. Aggressiveness assessed in adolescence was the only predictor of accident involvement in young adult age for males [2]. It also predicted self-reported driving while intoxicated after two years, but not speeding and fun riding [35]. Driving non-specific aggressiveness seems to be important predictor of driving behaviour after controlling some significant driving related variables. In a sample of Lithuanian drivers only aggressiveness explained accident involvement, when self-efficacy and driving anger was taken into account [36]. After controlling for hazard monitoring, thrill seeking, fatigue proneness, and dislike of driving, aggressiveness remained a significant factor to explain accident involvement and speeding on in-city roads, but not the speeding on highways in professional drivers [37]. In other study driving violations, lapses, and errors as measured by DBQ were explained by aggressiveness, when situational factors and impulsiveness were controlled [30]. Aggressiveness was found to be related with actual driving as well. People with higher scores of aggressiveness tend to speed more, brake later, pass through the yellow lights; they do not adjust their behaviour, when distraction task is given [38]. Contrary to this, Greaves and Ellison [18] found that self-reported speeding was related to aggressiveness, but actual speeding was not.

1.3. Research Question

- Mixed results on the effect of many personality traits on risky driving and consistent data on the role of aggressiveness lead us to presume that aggressiveness is the proximal predictor of risky driving behaviour (even aggression non-specific), while other personality traits have weaker contribution to driving behaviour. People with higher aggressiveness have lower inhibition threshold, thus, anger may be provoked immediately in frustrating situations [28]. In turn, anger may lead to active coping with the situation [39]; this may impair driving performance and lead to deliberate actions of violations on the road. Other personality traits, such as conscientiousness, extraversion or agreeableness, do not emit immediate emotional arousal and response; thus their role in driving behaviour could be rather distal [8]. Therefore, the role of personality traits should be further explored by using multivariate data analysis in order to control interrelations among personality traits and avoid invalid conclusions [5]. In the current study we focus only on aggression non-specific self-reported risky driving behaviour and its explanation. The research question of this study focuses on aggressiveness as the most important factor relating to self-reported risky driving. In order to explore the stability of the results in different contexts three samples consisting of experienced drivers, young drivers and drivers-learners were used to conduct the study. It has to be noted that initially research in these samples was aimed to answer broader research questions. For the purpose of this paper only data concerning personality and self-reported risky driving behaviour was employed. However, self-reported risky driving measure was not available for drivers-learners since they have no experience of independent driving. Instead, we assessed their attitudes towards traffic safety at the beginning of their driving classes. Based on the literature it was presumed that attitudes are quite a good predictor of later driving behaviour due to close relationship between attitudes towards safety and safety behaviour [21, 39, 40].

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- Sample 1 was composed from the larger study of Lithuanians and Lithuanian emigrants. For current analysis data of emigrants was omitted due to many cultural and environmental differences for Lithuanians living abroad. Sample of Lithuanians consisted of 284 drivers (48.2 percent males) aged 18-59 with mean age 32.58 (SD 10.17; median 31 years). The average years of driving experience were 10.40 (SD 8.63; ranging .5-37; median 8 years). The majority of drivers (78.5 percent) possessed B category driver licence (permission to drive a private car at age 18). In addition, a percentage of drivers also possessed A (motorcycle), C, or D (multiple passengers or heavy weight vehicles) category licence. Sample 2 consisted of 220 young Lithuanian drivers (55.5 percent of males), aged from 18 to 25 years (M = 22.11, SD= 1.73). The average years of driving experience were 3.77 (SD = 1.70; ranging .1-8.0; median 4 years). Almost all drivers (92.7 percent) possessed category B driver’s licence with few percent of category A, C, D licence holders. Participants in Sample 3 were drivers-learners in the first or second day of the driving training. Sample consisted of 361 (46.5 percent males) subjects aged 17-58 (M = 21.13 years, SD = 6.90) with majority (85 percent) of them being under 25 years of age. Due to significant age and driving experience differences, the samples in this paper were classified under three groups, namely “experienced drivers” (Sample 1), “young drivers” (Sample 2) and “drivers-learners” (Sample 3). All three samples were composed for different studies, which aimed to answer specific research questions. Nevertheless all three studies served for united purpose – to describe the personality of risky driver. As samples differed in their nature significantly and measures were not the same across the studies, it was decided to approach research question in 3 separate groups of drivers.

2.2. Measures

- Self-reported risky driving behaviour was assessed using Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (DBQ) [31]. The 24-item inventory was used. Originally DBQ yields three broad factors of self-reported driving behaviour: violations, errors, and lapses. In this study we used a two factor solution. Lapses and errors were considered as one factor because they were found to be highly correlated in Sample 1 and 2 (Spearman’s rho was .68 and .46, p<.001). Both factors accounted for approximately 39 percent of data variance in Sample 1 and 36 percent of data variance in Sample 2. The factor “errors” consisted of 16 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .87 in Sample 1 and .81 in Sample 2); the factor “violations” consisted of 8 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .79 in Sample 1 and .78 in Sample 2). DBQ was translated into Lithuanian using standard back–forward translation procedure. Scale of attitudes towards safe behaviour in the traffic served as a dependent variable in Sample 3. Because many drivers-learners had no experience in independent driving, their driving behaviour could not be assessed. This scale was composed by using 16 items from Attitudes Related to Traffic Safety by Iversen and Rundmo [21] and 8 items from the study of Wundersitz and Hutchinson [42]. It was chosen to merge two scales, because neither of single scale could cover different various behaviours on the road. In order to have one dependent variable instead of multiple (authors suggested either single item method or application of 3 scales) we combined all items together. Since Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory, we presume that new score of combined scale reflects one’s attitudes towards behaviour on the road. The items reflected one’s perception of an appropriate behaviour on the road (e.g. “Many traffic rules must be ignored to ensure traffic flow”; “If you are a good driver it is acceptable to drive a little faster”). A 5-point scale was used (1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree). Answers of some items were reversed, so that higher score of the scale reflected the non-acceptance of risky behaviour on the road. The internal consistency of the scale was satisfactory with Cronbach’s alpha = .70.Several instruments were included to measure personality traits. The Big Five Inventory (BFI) [43] was used to measure five personality traits – Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. In this study the short form of BFI consisting of 44 items was used. All five scales of BFI personality traits met the reliability requirement of scale application to the group comparison (see Table 1). Missing values were replaced with the mean value of the item for all personality variables. This procedure was applied only when missing data proportion was lower than 15 percent of all items; otherwise, subject was removed from dataset.

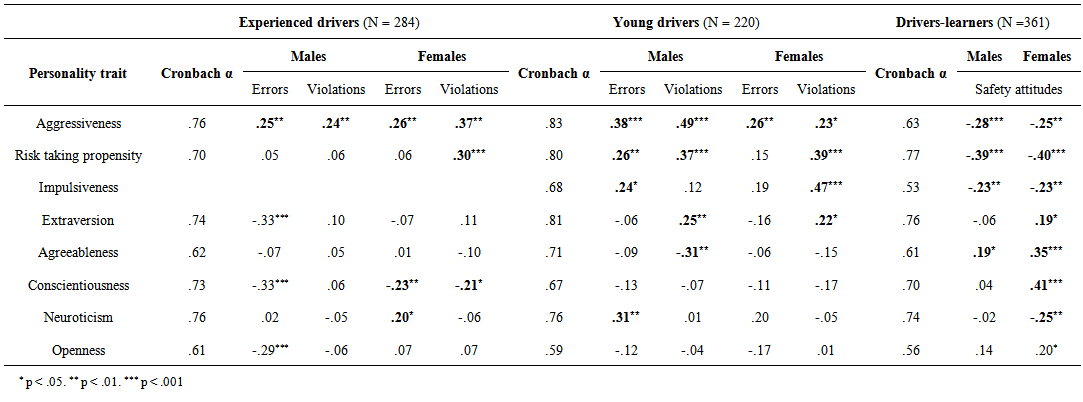

| Table 1. Partial zero-order correlations between personality traits and driving behaviour in male and female groups (controlled for age and driving experience in Sample 1 and Sample 2) |

2.3. Procedure

- Participants in Sample 1 (experienced drivers) were recruited using the snowball method – invited to participate person was encouraged to invite other people to take part in the study. One group of respondents was surveyed using paper-pencil questionnaire; while another group used a web-based questionnaire. No major differences were found between both groups neither in socio-demographic characteristics, nor in personality traits and driving behaviour. Respondents were informed that data would be treated in confidentially. As a result, a verbal consent was received from the respondent. For sample 2 (young drivers) volunteers were invited to fill the paper-pencil questionnaire. Respondents were informed that data would be treated in confidentially. A written consent form was obtained from the respondents.With the consent of the driving schools, drivers-learners (Sample 3) were approached and asked to participate in the longitudinal study. The participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to evaluate psychological issues in driving style development. The pencil-paper questionnaires were completed prior to the first or the second session of class. Researchers, who approached participants, were independent from driving schools. A written consent was obtained from the participants. They were informed that that data would be treated in confidentially. Only data of first wave of longitudinal study is presented in this paper.

3. Results

3.1. Gender Differences in Risky Driving

- Males and females differed in their self-reported driving behaviour. Females scored higher than males on the errors scale in the Sample 1 (mean rank 145.49 vs 122.12; Mann-Whitney U = 7385.5; p = .014), but there was no gender difference in this variable in the Sample 2 (mean rank 106.48 vs 108.80; Mann-Whitney U = 5517.5; p > .05). In both samples males reported more driving violations than females (mean rank 154.68 vs. 121.77; Mann-Whitney U = 7116.5; p = .001 in Sample 1 and mean rank 130.91 vs 83.70; Mann-Whitney U = 3365.5; p < .001 in Sample 2). Sample 3 data showed that males scored lower on attitudes towards traffic safety scale than females (with the mean scores of 71.89 (SD = 8.12) vs. 78.06 (SD = 8.21), t = -6,664; df = 310; p < .001). This result indicated that males displayed more positive attitude to towards risky behaviour on the road. Due to these differences all data analysis were run separately for male and female drivers groups. Knowing from theory that age and driving experience correlate with driving behaviour, the role of age and driving experience was controlled in the rest of the analysis (except for the Sample 3 where was low variance of the age and no licensed driving experience).

3.2. Zero Order Correlations for Driving Behaviour, Attitude towards Traffic Safety and Personality Traits

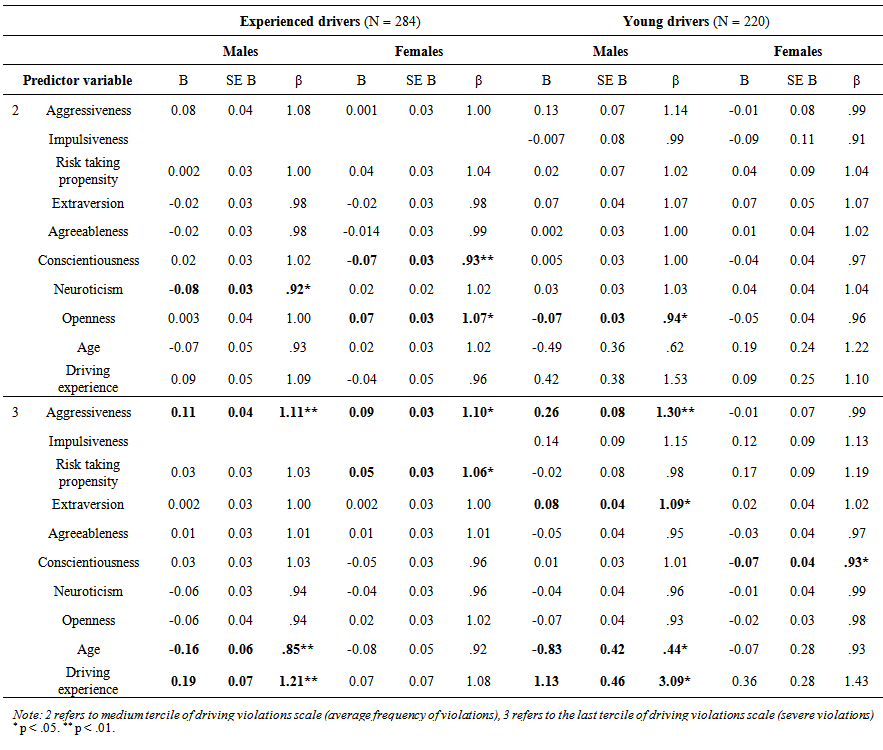

- First of all, correlations among driving behaviour (errors and deliberate violations), attitude towards traffic safety and personality traits were calculated for males and females separately (Table 1). Possible effect of respondents’ age and driving experience was controlled for Sample 1 and Sample 2. Results showed that aggressiveness correlated with higher scores of errors and violations in both samples and with safety risk acceptance in traffic attitudes. Risk taking propensity and impulsiveness correlated with errors and violations in Sample 2, but results were gender specific. Low scores of conscientiousness were related to self-reported risky driving, but only in Sample 1. Just several correlations reached statistical significance in the relationship of self-reported risky driving variables and extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness. Lower agreeableness was associated with violations of males, lower openness – with male driving errors. Higher neuroticism was related with errors across the samples. Interestingly, extraversion had positive correlation with violations in males, but correlated negatively with errors in samples of experienced and young males. The risky attitudes towards traffic safety were associated with higher risk taking propensity, impulsiveness, aggressiveness and lower agreeableness for male drivers-learners. In female group risk acceptance in traffic attitudes correlated with all personality traits. Several multinomial logistic regressions were conducted to investigate the relative strength of personality traits to explain driving errors and violations. Multinomial regression was chosen rather than linear, because dependent variables (errors and violations) differed significantly from normal distribution. For this analysis dependent variables were split into terciles, where the first tercile (no or weak behaviour) became the reference category. All personality traits, including Big Five traits, risk taking propensity, impulsiveness, and aggressiveness, were employed as independent variables. In order to distinguish the effect of aggressiveness as the proximal or distal variable we ran the regression analyses for aggressiveness as independent variable alone (controlling for age and driving experience effects). The results replicated correlation analyses in all samples: aggressiveness predicted self-reported driving errors and violations as well as traffic safety attitudes among experienced, young and drivers-learners.

3.3. Predictive Power of Personality Traits for Driving Behaviour

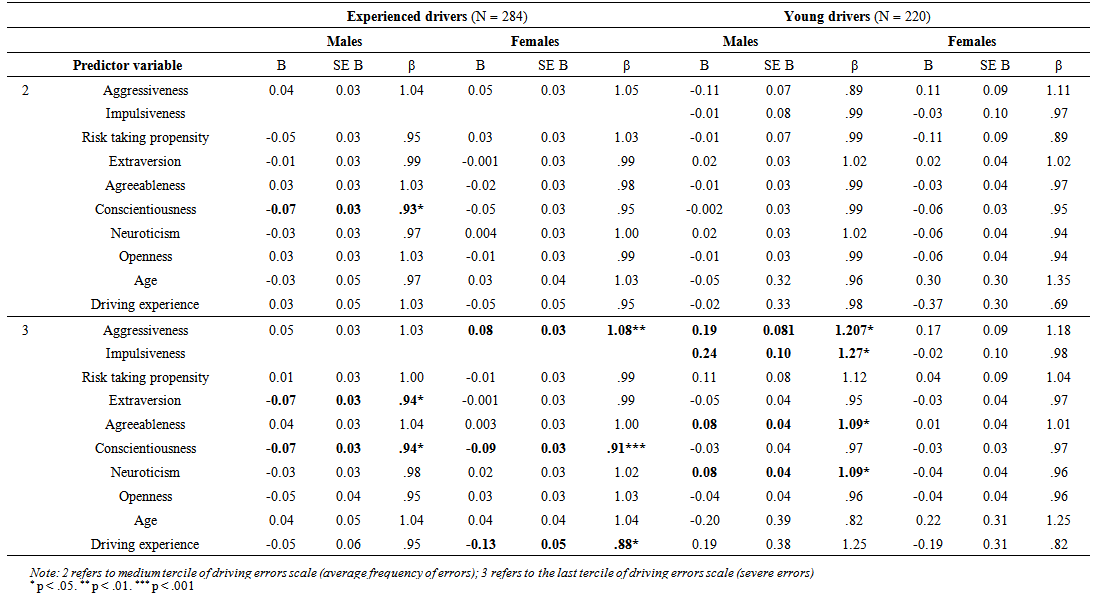

- The multinomial regression models of driving errors for males in Samples 1 and 2 fitted well to the observed data respectively (Chi-Square = 35.006; df = 18; p = .009 and Chi-Square = 49.498; df = 20; p < .001) and explained 28.3 (Sample 1) and 42.3 (Sample 2) percent of driving errors variance (Table 2). Results revealed that lower scores of conscientiousness increased the probability to belonging to the categories of medium and severe errors while driving and lower scores of extraversion increased the probability to belonging to the category of severe driving errors in Sample 1. As it could be expected from correlation analysis that personality traits accounting for driving errors of males in sample 2 differed from Sample 1. Results of regression analysis in males showed that probability to belong to the group of the biggest amount of driving errors increased when scores of neuroticism, aggressiveness, impulsiveness, and agreeableness became higher. Neither age nor driving experience was contributing for self-reported driving errors in males.

| Table 2. Summary of Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis for Predicting Driving Errors in Samples 1 and 2 |

| Table 3. Summary of Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis for Predicting Driving Violations in Samples 1 and 2 |

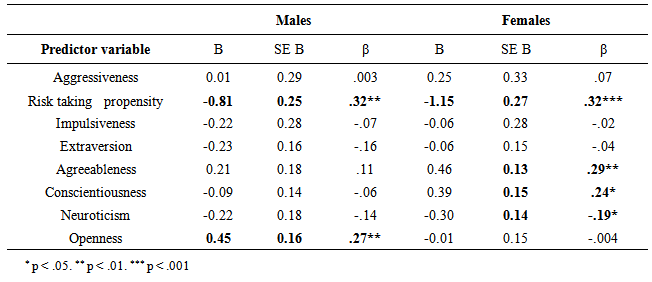

3.4. Predictive Power of Personality Traits for Attitudes towards Traffic Safety

- Linear regression models were created to predict the positive attitudes towards traffic safety in both male and female driver-learner groups. Linear regression was used because dependent variable did not differ from normal distribution significantly. The model of positive attitudes towards traffic safety was significant (F = 3.215, df = 8; p = .003) and had power to predict 18.9 percent of distribution of attitudes in males (Table 4). After considering all personality traits, only the lower scores of risk taking propensity and higher scores of openness had the unique significance in prediction of safety attitudes. Regression model in female group also was suitable for prediction of attitudes (F = 9.196, df = 8; p < .001) and had the power to explain 38.6 percent of the variance of dependent variable. More positive attitudes towards traffic safety were explained by lower scores of risk taking propensity and neuroticism, as well as higher scores of agreeableness and conscientiousness. Such personality traits as impulsiveness, aggressiveness, openness, and extraversion lost their value in predicting safety attitudes despite a significant correlation in the simple correlation analysis.

| Table 4. Summary of Linear Regression Analysis for Predicting Driving Attitudes (N 361) |

4. Discussion

- The aim of this paper was to evaluate the role of aggressiveness among other personality traits in the explanation of self-reported risky driving behaviour. It was presumed that aggressiveness, one of the most important personality traits, accounts for self-reported risky behaviour on the road. Numerous studies before documented that aggressiveness is strongly related with aggressive driving [32, 33]. However, data on the relationship between aggressiveness and other indicators of risky driving is not readily available [37]. Therefore, relationship between driving errors, traffic rule violations and trait aggressiveness were studied in this paper. Three groups of drivers with various levels of driving experience (experienced drivers, young drivers and drivers-learners) were chosen to assess the importance of aggressiveness in self-reported risky driving. It was hypothesized that aggressiveness will be the proximal predictor of self-reported driving errors and violations. It was also assumed that it is importance will be observed from the beginning of the driver’s career. Zero-order correlations supported this hypothesis. Aggressiveness seemed to be a universal variable, which was related to both driving errors and traffic rule violations in male and female samples regardless of driving experience. Also, it was related to the drivers-learners’ attitudes towards the traffic safety. These results support the idea that general aggressiveness might be an important predisposition for different aspects of aberrant driving behaviour [2, 32, 33, 37, 38]. Results of correlation analysis may lead to conclusion that aggressive people behave consistently, exhibit aggressive behaviour in various life situations, including driving [33]. However, multivariate analysis revealed a much more complicated picture.

4.1. Aggressiveness as a Distal Predictor of Attitudes towards Traffic Safety

- Three samples of drivers that differ in driving experience was an advantage but also a challenge of this study. Since the sample of student drivers did not have prior driving experience, the relationship between their attitudes towards safe behaviour in traffic and aggressiveness was assessed. Although it is believed that attitudinal variables are good predictors of later driving behaviour [21, 34, 49], the results of our study suggest that psychological mechanisms that lie above and beyond the self-reported risky driving and driving related attitudes differ significantly. Road safety attitudes of drivers-learners were predicted by risk taking propensity and Big Five personality traits (lack of openness to experience for men and neuroticism, lack of agreeableness and conscientiousness for women) but not by aggressiveness. After controlling the effects of certain personality traits, aggressiveness lost its unique ability to predict attitudes towards traffic safety. This implies that aggressiveness should be viewed only as a distal predictor of road safety attitudes. However, aggressiveness remained at least partially important in predicting driving behaviour in drivers’ samples. Discrepancies between attitudes and actual behaviour are well documented [50]. It could be presumed that attitudes towards any issue in society might reflect one’s beliefs, which have cognitive base, and in their core beliefs are conscious and deliberate [51], while aggressiveness seems to be emotion-driven reaction to various obstacles [52]. It is likely that drivers-learners have positively biased attitudes toward safe behaviour in the traffic. Reasons for this may be attributed to social desirability in learning situations but also the lack of independent driving experience. Although some research show a relationship between trait aggressiveness and safety attitudes in young drivers [34], it is unclear if these results can be applied for drivers-learners because they only reason about their future driving behaviour. Driving is a complex and situation related behaviour. It is doubtful that driver learner can accurately predict his or her reactions to future behaviour. Talking about attitudes does not involve any situational factors. This may explain why aggressiveness became only a distal predictor of road safety attitudes. The results of this study revealed that drivers-learners with a propensity to take risks in various situations express beliefs and behavioural intentions to act on the road in a manner contrary with traffic rules. It is reasonable to believe that people, who engage in multiple risks across different contexts in their life, are willing to take the risks in traffic related behaviour for the perceived personal benefits. Risky attitudes towards traffic safety were explained by a lack of openness for men and for women by neuroticism, lack of agreeableness and conscientiousness. As it was expected, a person with more positive characteristics (discipline, orientation towards others, positive emotionality, flexibility) possesses safer attitudes towards behaviour on the road as demonstrated views compatible with personality [53].

4.2. Aggressiveness as a Proximal Predictor of Driving Behaviour in Experienced Drivers

- In a sample of experienced drivers, aggressiveness was found to be a proximal predictor for female errors made while driving and traffic rule violations for both male and female drivers. These results support the idea that aggressiveness is one of the most important predictors of risky driving [30, 36, 38]. Data shows that hostile impulses may prompt intentional violations, as well as affect aggression non-specific performance, such as driving errors.In case of driving errors, aggressiveness together with conscientiousness and driving experience were the only significant predicting variables for females. Hostile impulses, lack of being concerned about following rules and lack of driving experience were related to driving errors. In male group, the scores of aggressiveness lost its value in predicting independently the occurrence of driving errors, but lower scores of conscientiousness and extraversion significantly explained making errors while driving. These results replicate the findings of other studies [8]. However, the question on why different mechanisms rule the presence of errors in the driving performances for males and females remains unanswered. The results of this study support the idea that aggressiveness might be considered as a proximal predictor of driving behaviour in experienced drivers, especially when conscious driving violations are analysed. When explanations of less deliberate driving faults are targeted, the lack of conscientiousness appeared among the main factors accounting for it.

4.3. Aggressiveness as a Proximal Predictor of Driving Behaviour in Young Males, but not Females

- Although the importance of aggressiveness for self-reported risky driving was confirmed in the sample of experienced drivers, the results for young drivers were less consistent. Aggressiveness was an important predictor of male errors and traffic rules violations, but failed to predict female self-reported risky driving behaviour. Research shows that in the etiology of young male self-reported risky driving, errors, violations, and aggressiveness play a more important role than other personality traits. Driving errors and traffic rule violations presumably are of different nature [54]. The mechanism of aggressiveness as being the strong predictor of making errors while driving in young males is unclear. It might be speculated, that hostile orientation towards others and their property may result in a lack of concern about the effect of own driving performance. This may lead to the occurrence of driving errors. It might be presumed that due to greater emotional inhibition of aggressive personality [27], a decrease of concentration during anger arousal state might lead to driving errors. Of course, such mechanisms should be subject to rigorous empirical validation.In addition to aggressiveness, other personality traits, such as impulsivity, agreeableness and neuroticism, appeared to be proximal predictors of the occurrence of error while driving. Extraversion, younger age and longer driving experience were proximal predictors of rule violations in young males. Contrary to the expectations, self-reported risky driving behaviour of young women could not be explained by aggressiveness even though correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between violations and aggressiveness, risk taking propensity, impulsiveness and extraversion. Conscientiousness was the only personality trait that was able to predict to a certain extent the occurrence of traffic rule violations in the female sample; lower scores of conscientiousness explained the highest amount of violations in females. These results support the idea that personality does not significantly contribute to driving errors and traffic rules violations in young women. This suggests that self-reported risky driving by young women is driven more by situation rather than personality [55, 56]. In summary, aggressiveness in young drivers, notably young males, should be perceived as a proximal predictor for self-reported risky driving. Self-reported risky driving of young women requires different explanatory models other than personality based. Aggressiveness has only secondary value, if any, in predicting traffic violations and errors by young female drivers.

4.4. Interpretation of Gender Differences for the Role of Aggressiveness in Risky Driving

- The results of this study cannot be explained by gender differences in driving behaviour and aggressiveness. Although behavioural differences across genders are well documented by numerous studies (see 57, 58], the explanation of underlying mechanisms of aggressive impulses on the road are inconclusive. According to evolutionary theory, men are more aggressive than women due to their culturally emerged sex roles and their body constitution, hormones and strength [27]. Studies have shown that males and females react differently in anger provoking situations [59, 60]. This approach has failed to explain why in the sample of experienced drivers aggressiveness accounted significantly for increased self-reported risky driving behaviour by females. The age and gender differences may be explained by the science of neuropsychology. According to Glendon [61], some brain areas that are important for behaviour regulation (prefrontal cortex, some subcortical regions, shifting balance between limbic and cortical systems, etc.) are still developing from the adolescence through the young adulthood. Because of neurodevelopmental trends among young people, this group in general is more prone to risky behaviour, act more impulsively, and get easily distracted and become frustrated. Amygdala develops later in males, and, according to Glendon [61], males have less brain tissue available to regulate their emotions. This would explain why young males as compared to females tend to respond more aggressively in driving situation. These gender differences become less evident as the brain develops. Although biological differences might be important, another interesting clue is the increasing value of aggressiveness for predicting self-reported risky driving of both males and females with the driving experience. These results might suggest the importance of experiential, social and cultural factors in contributing to expression of aggressive impulse to drivers. According to The General Aggression Model (GAM) [62], aggressive behaviour is not just a consequence of aggressive personality. Cycle of aggressive behaviour depends on personality and situational factors; situational internal states (i.e. cognition, arousal, affect) and outcomes of appraisal and decision-making processes. The valuable idea of GAM is concept of feedback loops that can influence future cycles of aggression. Feedback loops might be an important factor in explaining why aggressiveness cannot equally predict risky driving behaviour in different driver samples. Feedback about benefits of aggressive behaviour may reinforce future aggressive behaviours; on the other hand, negative feedback may inhibit aggressive behaviour in the future. These ideas are in line with Lajunen and Parker [60], who stated that aggressiveness on the road might also be seen as a learned problem – solving strategy that comes with driving experience. Some authors stressed that aggressive driving becomes more frequent and more socially acceptable way of expressing negative emotions [29]. So the relationship between aggressiveness and self-reported risky driving might have same development through experience. Drivers-learners with high trait aggressiveness do not plan to drive risky, but through exposure to various provoking situations and some feedback about benefits of risky driving finds out a new field for expression of aggressive personality style. Of course, these assumptions are very speculative due to a cross-sectional design of our study. Longitudinal data of driving style development is needed to support these hypotheses. Some other personality traits (conscientiousness, risk taking propensity, neuroticism, extraversion, and openness) should also be viewed as proximal predictors of risky behaviour. These findings partially replicate findings of other studies [7, 8, 63]. However, most relationships between Big Five personality traits and self-reported risky driving were either gender or behaviour specific. This is why these findings could be hardy generalized to other populations of drivers. The finding is also consistent with Greaves and Ellison [18], who revealed personality traits to be less important in prediction of self-reported behaviour, but significant in real driving. It could be concluded that on the large scale aggressiveness is one of the most important predictors of self-reported risky driving among other personality traits. Some implications of current result could be proposed. The reduction of aggressive behaviour should become a priority in risky driving prevention and intervention programs. It would be reasonable to expect a decrease in aggressiveness, if anger control techniques [64] or social skills, including problem solving are taught [65]. Successful efforts in reducing of aggressiveness may be two-fold: it is expected to prevent aggressive behaviour itself, as well as risky driving behaviour. The results of this study allows us to believe that driver education based on attitudinal changes over driving risks would be fairly effective, as it was reported by McKenna [66].

4.5. Limitations of the Study

- There were several limitations in the current study, therefore, the results should be interpreted and generalized with caution. The main concerns are self-report data, not random sample size, and cross-sectional methodology. The first issue is measurement based on self-report. Self-report data is the major concern in most road behaviour studies due to possible social desirability effects in answers [54]. Although, we succeeded to differentiate the role of aggressiveness in self-reported risky driving and attitudes towards traffic safety, different results may emerge in real driving situations. Results of our study and study by Greaves and Ellison [18] allow us to believe that the role of aggressiveness for risky driving is even greater than self-report is able to reveal. The use of more objective risky driving measures would be preferable. Data gathered for this study was based only on self-report of the respondents, common method variance and inflated correlations might be a problem in this study. Next, the results of the current study should be generalized to other populations with care. Volunteer participants may be not very representative sample. Issues of validity of the personality scales should be mentioned as a possible limitation as well. We considered the scales as valid and useful for the group comparison, based on the results and recommendations reported in literature [11, 67, 68]. Nevertheless, the higher validity of the scales would be desirable for more confident data.Moreover, cultural differences among various countries may have a different impact on aggressiveness and, subsequently, its role in risky driving behaviour. We believe that aggressiveness can be an important factor explaining various behaviours of Lithuanian people. The country is leading in the rates of many health-risk behaviours, like suicide, assault, heavy alcohol consumption etc. [1], which are related to aggressiveness as well. Cross-cultural studies and validation of the results would increase our understanding of aggressiveness and its role in risky driving behaviour.The cross-sectional nature of the study precludes the examination of causal relations or change over time. We used only a rather limited number of personality traits while many other factors might contribute to the development of risky driving behaviour. Further research should examine the broader context of driving and how this context interacts with individual personality characteristics and leads to risky driving behaviour.Final issue concerning limitations is the assumption that attitudes towards traffic safety are related to later risky driving behaviour and provide the information about the propensity to take risks while driving. Although some authors provide data that it is valid approach [21, 31, 69], others encourage being cautious with such presumptions [70].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We appreciate the support from the Research Council of Lithuania for this work: the study was partly funded by a grant No. T-09/08 and by a grant No. MIP-31/2010.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML