-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(1): 30-40

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140401.05

Exposure to Both Positive and Negative Pretrial Pubilicity Reduces or Eliminates Mock-Juror Bias

Chrisitne L. Ruva1, Mary Dickman2, Jessica L. Mayes3

1Department of Psychology, University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee, Sarasota, 34243, United States

2Department of Gender Studies, University of South Florida, Tampa, 33620, United States

3Department of Psychology, Marymount University, Arlington, VA 22207, United States

Correspondence to: Chrisitne L. Ruva, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee, Sarasota, 34243, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This experiment examined how exposure to both negative (anti-defendant) and positive (pro-defendant) pretrial publicity (PTP) affects juror memory and verdicts. Mock-jurors were exposed to eight PTP stories over 10 to 12 days. Pure-PTP mock-jurors received only one type of PTP (negative, positive, or unrelated). Mixed-PTP mock-jurors received both types of PTP in either an alternating (e.g., negative, positive, negative, positive) or a blocked fashion (e.g., negative, negative, positive, positive). Mock-jurors in the negative PTP (N-PTP) condition had a greater proportion of guilty verdicts and had higher guilt ratings than positive PTP (P-PTP) and unrelated PTP (U-PTP) mock-jurors; thus demonstrating a pro-prosecution bias. The mock-jurors in the P-PTP condition demonstrated a pro-defense bias by being less likely to vote guilty and having lower guilt ratings than the U-PTP jurors. Regardless of presentation order, mixed-PTP exposure reduced or eliminated PTP’s biasing effects on verdicts, with mixed jurors’ verdict distributions most closely resembling those of U-PTP jurors. For guilt ratings there was also evidence PTP bias reduction for blocked jurors, while alternating jurors demonstrated a recency effect. As for source memory, mock-jurors in the N-PTP condition made a greater proportion of negative PTP errors than mock-jurors in the P-PTP, U-PTP, and some of the mixed conditions. The authors suggest that the trend for lower source memory errors in this study, as compared to similar past research, may be due to increased temporal and environmental cues afforded by the spaced PTP exposure. Additionally, the smaller proportion of critical source memory errors for mixed-PTP jurors than for pure-PTP jurors may be due to differences in these jurors’ memory for PTP facts.

Keywords: Juror decision making, Juror memory, Source memory, Pretrial publicity, Primacy effect, Recency effect

Cite this paper: Chrisitne L. Ruva, Mary Dickman, Jessica L. Mayes, Exposure to Both Positive and Negative Pretrial Pubilicity Reduces or Eliminates Mock-Juror Bias, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 30-40. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140401.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Research has demonstrated that exposure to pretrial publicity (PTP) can bias both juror and jury decision making[1-5]. Banks[6] argues that regardless of the intelligence, people are highly influenced by what they read, see, and hear in the media. Advancements in technology have made media more accessible. Therefore, it is reasonable to question whether finding an unbiased jury is possible when a case has received sensational media coverage[7]. This question is at the heart of the conflict between the US Constitution’s First and Sixth Amendments. The First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press and protects the publics’ right to know about criminal trials. The Sixth Amendment is the right of the defendant to a fair trial by an impartial jury[5]. Clearly these rights are at conflict in high publicity cases in which the defendant is portrayed in a negative manner.Negative (anti-defendant) PTP receives more media covered than other types of PTP (e.g., positive or negative victim) and is the focus of PTP research[8-10]. Research has shown that jurors who read negative PTP are more likely than jurors who are not exposed to negative PTP to indicate that the defendant is guilty (see Steblay et al., 1999 for review). Although positive (pro-defendant) PTP is not as prevalent as negative PTP, recent research suggests that it tobiases jurors’ decisions. For example, Ruva and McEvoy[11] and Ruva, Guenther, and Yarbrough[12] found that mock-jurors who read positive PTP were significantly less likely to vote guilty than jurors who were not exposed to PTP. Additionally, Kovera[13] had mock-jurors view one of three general PTP stories about rape (pro-prosecution, pro-defense, or unrelated) and then indicate how much evidence they would require to convict a defendant accused of rape. Kovera found that individuals who watched pro-defense story indicated that they would require more corroborating evidence toconvict than participants who read the pro-prosecution story.The PTP research discussed above demonstrates that the biasing effects of negative and positive PTP pull juror verdicts in opposite directions (towards guilty vs. not guilty). The major impetus for the research presented in this paper was to explore how exposure to roughly equal amounts of positive and negative PTP affects PTP bias. That is, would there be an amelioration of PTP bias? Also, how would the order of the presentation of negative and positive PTP stories affect PTP’s influence on juror verdicts? To examine these questions, we randomly assigned participants to one of seven conditions (see Appendix A) with some jurors exposed to only one type of PTP (pure conditions) and other jurors receiving a mixture of negative and positive PTP (mixed conditions). There were three pure-PTP conditions: (1) negative PTP only (N-PTP), (2) positive PTP only (P-PTP), and unrelated PTP only (U-PTP). The unrelated PTP consisted of eight crime stories unrelated to the case presented at trial. In order to test order effects, we had four different orders of PTP exposure for the mixed-PTP conditions. Two of the mixed conditions were labeled alternating. In these conditions the first story was either positive (APN) or negative (ANP) and the next story was the opposite and this alternating pattern continued through all eight stories (see Appendix A). The remaining mixed conditions were labeled blocked (BNP and BPN) due to participants receiving the two types of PTP in a blocked fashion. Jurors in the BNP conditions received four negative PTP stories first followed by four positive stories; whereas those in the BPN condition received four positive PTP stories first followed by four negative PTP stories.The research presented here is the second study(that the authors are aware of) to expose jurors to PTP in a spaced fashion, which is more ecologically valid than the typical mass exposure (single session). The first study was conducted by Ruva, Mayes, Dickman, and McEvoy[14] and our procedures are similar to theirs. The main difference being that the present study eliminated the predecisional distortion questions following each PTP story. This was done to increase ecological validity. Actual jurors are not asked to answer these types of questions when naturally exposed to PTP, and research suggests that answering these questions could have an effect on how information is weighted. For example, according to the attention decrement hypothesis, experimental conditions influence whether primacy or recency effects are observed[15]. As Ruva and associates[14] noted, if the participants are only required to make a final judgment, primacy effects are likely, as decreased attention may be paid to later information. When participants are required to make multiple judgments they may increase their attention to later information, resulting in recency effects.” This study also differs from Ruva and associates by exploring how pure versus mixed-PTP exposure affect source memory.

1.1. Primacy and Recency Effects

- With the possibility of real jurors being exposed to both positive (pro-defendant) and negative (anti-defendant) PTP it is important to explore whether earlier or later information has a greater effect on decision making. Previous research has resulted in mixed findings regarding order effects for evidence presentation, both recency[16-19] and primacy[20, 21] effects have been found. Costabile and Klein[16] found recency effects with mock-jurors being more likely to render guilty verdicts when incriminating evidence was presented at the end of the trial than when it was presented at the beginning. They attribute this recency effect to the jurors’ ability to recall the evidence presented later in the trial when rendering verdicts. Kerstholt and Jackson[19] and Furnham’s[18] research provides additional support for recency effects in that jurors receiving prosecution evidence last were more likely to render guilty verdicts than jurors receiving defence evidence last. Other research has found primacy effects. Carlson and Russo[20], using the predecisional distortion paradigm, found that witness affidavits presented earlier in mock trials had more influence on jurors’ verdicts than those presented later in the trial. Schum[21] also found a primacy effect with mock-juror either reinterpreting or ignoring later testimony that conflicted with prior evidence or testimony. Primacy effects have also been found for impression formation, with information that is acquired initially about a person being weighted more heavily than later information [22-24]. Anderson[15] proposed two hypotheses to explain the primacy effect in impression formation: (1) attention decrement hypothesis and (2) the discounting explanation. According to attention decrement hypothesis, once impressions become crystallized new information will be viewed as unneeded and hence little attention will be paid to it[22]. Similar to the story model and consistent with Schum’s[21] research findings, the discounting explanation posits that when later information about a person is inconsistent with earlier information it will be discounted and/or given less weight[23]. Devine and Ostrom[25] examined whether the discounting theory could explain the effects of inconsistent trial testimony on story creation. The researchers found that mock-jurors discount inconsistent testimony in order to create a story that explained the trial events.Finally, Ruva et al.[14] exposed mock-jurors to 8 PTP stories over a period of 10 to 12 days with some jurors only being exposed to one type of PTP and others begin exposed to both positive and negative PTP in either a blocked or alternating manner. Then one week after reading the final PTP story these jurors were exposed to a criminal murder trial. Immediately following the reading each PTP story they asked jurors to indicate the winning side (prosecution or defense) and found a recency effect for these decisions. For verdicts they found a primacy effect for mock-jurors receiving mixed PTP in a blocked manner, but an amelioration of PTP bias for those receiving mixed PTP in an alternating fashion.

1.2. Spacing Effects on Memory and Decision Making

- In addition to exploring primacy and recency effects the current research is also important because it exposes jurors to PTP over multiple sessions spaced over 10 to 12 days; thereby introducing the concept of spacing and a procedure that allows for more ecologically valid PTP exposure. Research exploring the effects of massed vs. spaced (or distributed) learning has consistently found that spaced learning leads to better memory[26-29] and may be more effective for learning[30]. Explanations of the spacing effect include: (1) people pay less attention (have lowered interest) to repetitions under massed conditions than under spaced conditions and (2) spacing is beneficial because the contextual variability (temporal, physical, or mental) at time of encoding can enhance memory[30]. Although the research on spaced vs. massed learning indicates that memory is better in the former rather than the latter, it is not clear what effect it might have on decisions. One possibility is that spacing of PTP could lead to each story having a greater individual impact on jurors’ decisions due increased memory. The examination of PTP effects under spaced rather than mass exposure conditions is beneficial because it more closely mimics how actual jurors are exposed to PTP; thus the spaced procedure might tell us more about how PTP affects actual jurors.

1.3. Source Memory

- Source memory focuses on judgments about the origin or source of information[31, 32]. The accuracy of source decisions can be improved by clearly remembered details, distinct possible sources (e.g., different contextual or temporal cues), and relatively stringent decision[33]. Source memory helps us differentiate reliable from unreliable information. Inability to accurately determine the source of information can have serious implications on use of knowledge and beliefs[31]. For example, accurate source memory is necessary for jurors to abide by judicial instructions explaining that they cannot use PTP when making verdict decisions and must base their decisions solely on evidence presented at trial. Ruva and associates[5, 11] that PTP exposed jurors were more likely than non-exposed jurors to misattribute PTP information to the trial and were more confident in doing so. These critical source memory errors were also found to mediate the effect of PTP on guilt ratings and therefore may be a mechanism through which PTP imparts its biasing effect on juror decision making. We explore below how our more ecologically valid (spaced) presentation of PTP may affect the accuracy of mock-jurors’ source memory judgments.It is clear from previous work that spaced presentations enhance item memory (relative to massed presentations), but the effects of spacing on memory for context (or source) is less clear[34]. For example, Benjamin and Craik presented words to participants under massed (no delay) or spaced (5 minute delay) conditions in order to explore the effects of spacing on recognition memory and memory for context. Results from the recognition test showed that spacing increased performance by 10% in both younger and older participants. For younger adults spacing tended to enhance source memory performance; they were more likely to reject words from the to-be-rejected list after spaced versus massed exposure (this did not occur for older adults).The ease and accuracy with which the source of a memory is identified is determined by several factors: (a) the type and amount memory characteristics included in activated memory records (perceptual information, contextual information – spatial and temporal, emotions reactions, and cognitive operations), (b) how unique these characteristics are for given sources (the more similar the memory characteristics from two or more sources, the more difficult it will be to specify source correctly), and (c) the efficacy of the judgment processes by which source decisions are made and nature of criteria used[32]. In the present study, it was expected that the additional source cues provided (e.g., context of internet vs. lab and temporal cues), would increase source memory performance in mock jurors.

1.4. Summary

- The research above suggests that PTP can bias juror decision making and that the order in which trial evidence is presented can impact its influence on jurors’ decisions. Past PTP research has typically used a massed exposure procedure and has exposed jurors to only one type of PTP [14]. The spacing of the PTP exposure over multiple weeks as well as exposing jurors to different types of PTP (negative and positive) allowed us to explore whether PTP information presented first or last will have the greatest effect on juror decisions. In addition, the mixed-PTP conditions allowed us to explore whether PTP’s biasing effects would be less (or be ameliorated) in the mixed-PTP conditions as compared to the pure-PTP conditions; and whether there is a cumulative effect of PTP in the pure conditions. Finally, the spacing of PTP exposure allowed us to explore PTP effects in a more ecologically valid paradigm, which more closely mimics how actual jurors receive PTP. The following hypotheses were tested.

1.5. Hypotheses

- 1. For the pure PTP conditions, N-PTP mock-jurors are expected to have a greater proportion of guilty verdicts and have higher guilt ratings than the P-PTP and U-PTP mock-jurors. In addition, P-PTP mock-jurors are expected to have a greater proportion of not guilty verdicts and have lower guilt ratings than U-PTP mock-jurors[1-5, 7, 14].2a. In the blocked PTP conditions primacy effectswere expected[14, 20-24]. In these conditions we expected that the first stories mock-jurors were exposed to would have the largest effect on verdicts and guilt ratings. Mock-jurors who were exposed to the negative PTP stories first (BNP condition) were expected to have a greater proportion of guilty verdicts and to have higher guilt ratings than the P-PTP and the U-PTP mock-jurors. BNP jurors were not expected to significantly differ from the N-PTP mock-jurors on any either of these guilt measures. 2b. Mock-jurors exposed to the positive PTP stories first (BPN condition) were expected to have a greater proportion of guilty verdicts and to have lower guilt ratings than the N-PTP and the U-PTP mock-jurors. BPNmock-jurors were not expected to significantly differ from the P-PTP on either of these guilt measures.3. The mock-jurors in the alternating conditions (ANP and APN) were expected to have verdicts and guilt ratings that resemble those of the U-PTP mock-jurors. These results were expected due to the point-counter point presentation of the PTP which should lead to a balancing out of the PTP bias[14]. The alternating mock-jurors were also expected to have a smaller proportion of guilty verdicts and to have lower guilt ratings than the N-PTP mock- jurors but to have a greater proportion of guilty verdicts and have higher guilt ratings than the P-PTP mock-jurors.4. Mock-jurors exposed to PTP were expected to make more critical SM errors (misattributing information in the PTP to the trial) than those not exposed to PTP[5, 11]. Specifically, those exposed to negative PTP would make a greater proportion of negative-PTP critical SM errors than mock-jurors not exposed to negative PTP. Mock-jurors exposed to positive PTP would make a greater proportion of positive-PTP critical SM errors than those not exposed to positive PTP.5. Mock-jurors exposed to PTP were expected to be more confident in their critical SM errors[5, 11]. Specifically, those exposed to negative PTP would be more confident in their negative-PTP critical SM errors than jurors not exposed to negative PTP. Mock-jurors exposed to positive PTP would be more confident in their positive-PTP critical SM errors than those not exposed to positive PTP.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- The participants were 345 university students (76 men and 269 women) whom received extra course credit for their participation in this experiment. Ages ranged from 18 to 51 years (M= 21.48, SD = 4.86). The sample consisted of 60% White, 15% Hispanic, 14% African American, 6% Asian/ Pacific Islander, and 6% other. After the participants completed phase 1 of the experiment, they were randomly assigned to one of the seven PTP conditions (discussed below). Although our sample is racially diverse, it still consisted of mostly Caucasian college students who are United States citizens. Therefore, our finding should be interpreted in this context and may be culturally bound. In addition, our sample was predominately female, which may not be representative of the typical criminal jury composition.

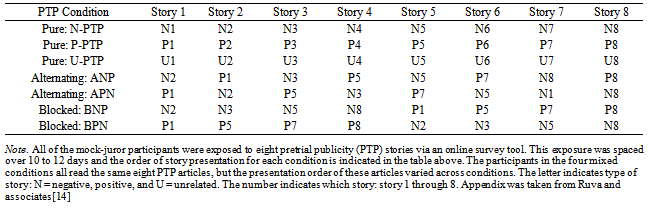

2.2. Design

- This experiment utilized a between subjects design. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the seven PTP conditions (N-PTP, P-PTP, U-PTP, ANP, APN, BNP, and BPN; refer to Appendix A). There were 48 participants in the N-PTP and P-PTP conditions, 49 participants in the APN and ANP conditions, 50 participants in MPN and MNP and 51 participants in the U-PTP. All of the conditions except for the U-PTP received PTP about the defendant in the stimulus trial. The U-PTP mock-jurors read eight different crime stories that were unrelated to the case involving the defendant. The use of mock-jurors and trial simulation (experimental design) in the present study has advantages over field or survey research utilizing actual jurors. The main advantage is that of increased internal validity, which allows researchers to infer causation. This is due to the additional control that researchers have in the lab and the use of random assignment of mock-jurors to experimental condition, and thus guaranteeing equivalence of important participant variables across conditions. The main disadvantage to using an experimental design over a field study is a reduction in ecological validity of mundane realism. As our methods below suggest that although ecological validity may be reduced over that of a field study, we did several things to increase it (e.g., use of real trial and PTP, spacing of PTP over time, and using different types of PTP.

2.3. Stimuli

2.3.1. Trial

- The stimulus trial was an actual videotaped criminal trial in which a man is accused of murdering his wife (NJ v Bias). The trial stimulus was edited to run 30 minutes. Results from previous research[12, 35-37] indicate that this trial stimulus is ambiguous as to the defendant’s guilt. Ambiguous trials are preferable because they better illustrate the biasing effect PTP[2, 38] and provide a more ecologically valid stimulus [39] than unambiguous trials.

2.3.2. Pretrial Publicity

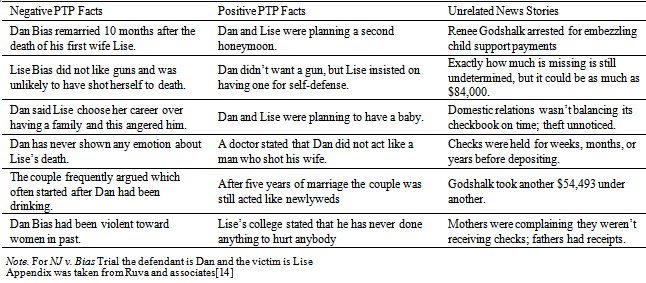

- All participants, except those in the U-PTP condition, read eight news articles that were modified from actual PTP from the NJ v Bias trial. These stories provided general information about the case (e.g., identified the victim, when and where the crime took place, and provided a description of the crime). These stories contained information that was not presented at trial and thus this information could have a biasing effect on juror verdicts (see Appendix B for a sample of each type of PTP information). In the pure conditions (N-PTP and P-PTP) jurors read eight articles of the same valence. In the four mixed conditions (ANP, APN, BNP, and BPN) jurors read the same eight PTP articles, except the order of presentation varied in each condition (see Appendix A). Although jurors in the mixed conditions and pure conditions were exposed to all of the same positive and negative PTP facts, the jurors in the pure conditions (N-PTP and P-PTP) were exposed to each fact more times than jurors in the mixed conditions. Participants in the U-PTP conditions read news articles involving eight different crimes unrelated to each other or the case involving the defendant. These news stories involved crimes such as embezzlement, burglary, criminal mischief and fraud (see Appendix B).

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Verdicts and Guilt Ratings

- After viewing the trial, participants were asked to render verdicts (guilty or not guilty) and to their confidence in their verdicts on a 7-point Likert scale (1 indicating not at all confident, midpoint rating of 4 indicating that the participant was unsure, and 7 indicating completely confident). Guilt ratings were then calculated by multiplying the participants’ confidence rating by -1 if they had rendered a not guilty verdict and by +1 if they had rendered a guilty verdict. This resulted in a 14-point scale with -7 indicating a not guilty verdict and complete confidence in this decision and +7 indicating a guilty verdict and complete confidence in this decision.

2.4.2. Source Memory Test (SM)

- Participants indicated whether they were exposed to a particular statement during the trial (T), the crime stories (C), both the trial and the crime stories (B), or that the statement was new (N: it had not been presented during either the trial or the crimes stories). This test contained statements presented only in the trial, statements provided only in the PTP, statements provided only in the unrelated articles, and statements not provided in either the PTP or the trial. Each statement received a SM judgment and a confidence rating. For the confidence ratings, participants used a 7-point Likert scale to rate their confidence in each SM judgment they made (1 indicating not at all confident and 7 indicating extremely/completely confident) regarding the source of the statement.

2.5. Procedure

- This experiment was conducted in three phases, which are explained below. The procedure used in the present study is similar to that of Ruva and associates[14]. The main difference between the two studies is that the present does not include the predecisional distortion questions in each online survey. This removal of these questions was done in order to increase the ecological validity of the study—actual jurors are not asked to answer such questions after being exposed to PTP.

2.5.1. First Phase

- During phase 1, participants were run in groups of 12 or fewer and were randomly assigned to one of the seven PTP conditions. The first task that participants completed was a demographic questionnaire. The participants were given both written and verbal instructions of how to complete the online portion of the experiment (described below). Before being excused participants were reminded that they would be completing their first online survey the following day. Participants received an email later that day containing instructions for the online portion this also served to verify that the researchers had their correct email address.

2.5.2. Second Phase: Online Surveys

- Over a period of 10 to 12 days mock-jurors were exposed to PTP through eight crime stories which they read online. Each morning the mock-jurors received an email from a researcher notify them that the days survey was available for them to complete and that they had until 11:59 pm that day to complete it. In order to ensure that participants completed each day’s survey within this time period, access to the surveys were password restricted (Sona Systems) and each survey was available to participants for this specific period of time (12 to 14 hours). Each survey consisted of one PTP article/story and six open-ended memory questions. The memory questions were used to verify that participants were reading the PTP articles. Participants’ performance on these memory questions were checked daily by a researcher. If participants answered more than three questions incorrectly they warned via email of their poor performance and that they would be disqualified from the study if their poor performance continued. If participants did not complete a survey on the day it was assigned, they were sent an email instructing to complete the missed survey the following day. If the participant missed more than two surveys they were disqualified and did not participate in phase 3 of the experiment.

2.5.3. Third Phase: Trial Presentation and Verdicts

- Approximately one week after exposure to the final PTP article participants returned to the lab and viewed a videotaped murder trial. After viewing the entire trial, participants were instructed to act as if they were jurors in an actual trial, and like actual jurors they could only use the evidence presented during the trial when making decisions regarding guilt. Participants then rendered verdicts, completed the source memory test, and debriefing questionnaire.

3. Results

- For all analyses the alpha level for significance was set at .05. Effect sizes are reported as omega squares

for ANOVAs and as Cramer’s V for chi squares.

for ANOVAs and as Cramer’s V for chi squares.3.1. Hypothesis 1: Pure PTP Guilt Measures

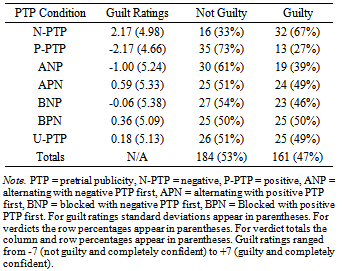

- Chi squares were used to test our verdict hypotheses and one-way ANOVAs (PTP: N-PTP, P-PTP, ANP, APN, BNP, BPN or U-PTP) and contrasts were conducted to test our guilt rating hypotheses. Exposure to PTP had a significant main effect on juror verdicts and guilt ratings, χ2(6, N = 345) = 16.79, V = .22, F(6, 338) = 3.33, MSE = 26.25,

.05, ps< .01. As expected, N-PTP jurors were more likely to vote guilty and provide higher guilt ratings than jurors in the P-PTP and U-PTP conditions (see Table 1), χ2(1, Ns = 96 and 99) = 15.10 and 3.15, V = .39 and .18, Fs(1, 90 and 93) = 17.17 and 4.28, MSE = 26.25,

.05, ps< .01. As expected, N-PTP jurors were more likely to vote guilty and provide higher guilt ratings than jurors in the P-PTP and U-PTP conditions (see Table 1), χ2(1, Ns = 96 and 99) = 15.10 and 3.15, V = .39 and .18, Fs(1, 90 and 93) = 17.17 and 4.28, MSE = 26.25,  .16 and .03, ps< .05. Also as expected, P-PTP jurors were less likely to vote guilty than U-PTP jurors, χ2(1, N = 96) = 5.03, V = .22, F(1, 95) = 5.17, MSE = 26.25,

.16 and .03, ps< .05. Also as expected, P-PTP jurors were less likely to vote guilty than U-PTP jurors, χ2(1, N = 96) = 5.03, V = .22, F(1, 95) = 5.17, MSE = 26.25,  .04, ps< .05.

.04, ps< .05.

|

3.2. Hypothesis 2: Blocked PTP Guilt Measures

- Jurors in the blocked conditions (BNP and BPN) were expected to demonstrate a primacy effect in which early PTP would have a greater impact on verdicts and guilt ratings than later PTP. As expected, BNP jurors (received negative PTP first) were significantly more likely to vote guilty and have higher guilt ratings than P-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 98) = 3.77, V = .20, p< .05, F(1, 96) = 4.14, MSE = 26.25,

.03, ps< .05. Contrary to our expectations, BNP jurors were significantly less likely to vote guilty and had significantly lower guilt ratings than N-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 98) = 4.25, V = .21, F(1, 92) = 4.63, MSE = 26.25,

.03, ps< .05. Contrary to our expectations, BNP jurors were significantly less likely to vote guilty and had significantly lower guilt ratings than N-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 98) = 4.25, V = .21, F(1, 92) = 4.63, MSE = 26.25,  = .03, ps < .05. Also, contrary to our expectations, BNP jurors did not significantly differ from U-PTP jurors on verdicts or guilt ratings (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 100) = 0.09 and F(1,94) = 0.05, MSE = 26.25, p = .82.Contrary to our primacy effect hypotheses, jurors in the BPN condition (received positive PTP first) were significantly more likely to vote guilty and had higher guilt ratings than P-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 98) = 5.42, V = .24 and F(1, 92) = 5.96, MSE = 26.25,

= .03, ps < .05. Also, contrary to our expectations, BNP jurors did not significantly differ from U-PTP jurors on verdicts or guilt ratings (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 100) = 0.09 and F(1,94) = 0.05, MSE = 26.25, p = .82.Contrary to our primacy effect hypotheses, jurors in the BPN condition (received positive PTP first) were significantly more likely to vote guilty and had higher guilt ratings than P-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 98) = 5.42, V = .24 and F(1, 92) = 5.96, MSE = 26.25,  .05, ps < .05. BPN jurors were significantly less likely to vote guilty than N-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 98) = 2.80, V = .17, p < .05, but the difference in these groups’ mean guilt ratings did not reach statistical significance, F(1, 92) = 3.05, MSE = 26.25, p = .08. Finally, BPN jurors did not significantly differ from U-PTP jurors on verdicts or guilt ratings (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 101) = 0.01 and F(1, 95) = 0.03, MSE = 26.25, p = .86. In summary, contrary to our predictions we did not find evidence of a primacy effect for the blocked conditions. Instead, regardless of which type of PTP the blocked jurors were exposed to first, their guilt measures most closely resembled those of U-PTP jurors. Hence blocked exposure appears to have ameliorated the effect of PTP on jurors’ guilt decisions.

.05, ps < .05. BPN jurors were significantly less likely to vote guilty than N-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 98) = 2.80, V = .17, p < .05, but the difference in these groups’ mean guilt ratings did not reach statistical significance, F(1, 92) = 3.05, MSE = 26.25, p = .08. Finally, BPN jurors did not significantly differ from U-PTP jurors on verdicts or guilt ratings (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 101) = 0.01 and F(1, 95) = 0.03, MSE = 26.25, p = .86. In summary, contrary to our predictions we did not find evidence of a primacy effect for the blocked conditions. Instead, regardless of which type of PTP the blocked jurors were exposed to first, their guilt measures most closely resembled those of U-PTP jurors. Hence blocked exposure appears to have ameliorated the effect of PTP on jurors’ guilt decisions.3.3. Hypothesis 3: Alternating PTP Guilt Measures

- We expected that the point-counterpoint presentation of PTP in the alternating conditions (ANP and APN) would lead to a leveling in bias, such that these jurors would have verdict distributions similar to those of U-PTP jurors. As expected, verdicts and guilt ratings for jurors in the alternating conditions did not significantly differ from the U-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2s(1, Ns = 100) = 1.06 and 0.00, ps> .09, Fs(1, 94) = 1.07 and 0.38, MSE = 26.25, ps> .30. Also as expected, jurors in the ANP and APN conditions were significantly less likely to vote guilty than N-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2s(1, N = 97) = 7.57 and 3.11, Vs = .28 and .18, ps< .05. The results for the guilt ratings are more complicated, with jurors in the ANP condition having significantly lower guilt ratings than jurors in the N-PTP condition, F(1, 91) = 9.39, MSE = 26.25,

.08, p< .05, but mean guilt rating for APN and N-PTP did not significantly differ, F(1, 91) = 2.08, MSE = 26.25, p = .14. As expected, APN jurors were significantly more likely to vote guilty and have higher guilt ratings than P-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 97) = 4.92, V = .23, F(1, 91) = 7.03, MSE = 26.25,

.08, p< .05, but mean guilt rating for APN and N-PTP did not significantly differ, F(1, 91) = 2.08, MSE = 26.25, p = .14. As expected, APN jurors were significantly more likely to vote guilty and have higher guilt ratings than P-PTP jurors (see Table 1), χ2(1, N = 97) = 4.92, V = .23, F(1, 91) = 7.03, MSE = 26.25,  .06, p< .05, but verdict and guilt ratings differences between ANP and P-PTP jurors did not reach statistical significance, χ2(1, N = 97) = 1.50, F(1, 91) = 1.28, MSE = 26.25, ps > .08. These results suggest that presenting mixed PTP in an alternating fashion resulted in a reduction of PTP bias, with alternating jurors’ verdicts closely resembling those of U-PTP jurors. That being said, the more sensitive measure of guilt ratings suggested that PTP bias was not eliminated and that a recency effect may be at work. As can be seen in Table 1, the ANP jurors (whose last PTP story was positive) had guilt ratings similar to those of P-PTP jurors, and APN jurors’ guilt ratings (whose last story was negative) more closely resembled those of N-PTP jurors.

.06, p< .05, but verdict and guilt ratings differences between ANP and P-PTP jurors did not reach statistical significance, χ2(1, N = 97) = 1.50, F(1, 91) = 1.28, MSE = 26.25, ps > .08. These results suggest that presenting mixed PTP in an alternating fashion resulted in a reduction of PTP bias, with alternating jurors’ verdicts closely resembling those of U-PTP jurors. That being said, the more sensitive measure of guilt ratings suggested that PTP bias was not eliminated and that a recency effect may be at work. As can be seen in Table 1, the ANP jurors (whose last PTP story was positive) had guilt ratings similar to those of P-PTP jurors, and APN jurors’ guilt ratings (whose last story was negative) more closely resembled those of N-PTP jurors.3.4. Hypothesis 4: Critical Source Memory Errors

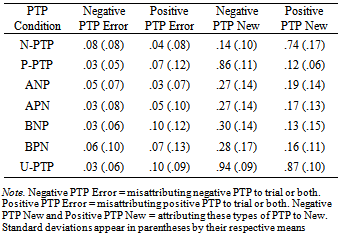

- The critical source monitoring errors of interest were those in which participants misattributed information contained only in the PTP as appearing in the trial or in both the trial and the PTP (Zaragoza & Lane, 1994). Corrected error scores for each participant (see Table 2) were calculated by taking each participant’s initial error score and subtracting from this the proportion of new items (those not presented in either the trial or the PTP) the participant identified as being either in the trial or in both the trial and the PTP. Then two between-subjects ANOVAs were performed on the source monitoring error measure (corrected error scores), one for the negative PTP critical errors and one for the positive PTP critical errors, in order to test the prediction that PTP exposure would have a significant effect on source monitoring errors. PTP exposure had a significant effect on both negative PTP and positive PTP critical errors, Fs(6, 338) = 3.17 and 3.51, MSEs = 0.01 and 0.01, ps< .01,

.05 and .06, respectively. Jurors exposed to only negative PTP (N-PTP condition) made a greater number of negative PTP errors than jurors in the P-PTP, APN, BNP, and U-PTP conditions (see Table 2), Fs (1, 96 or 97) = 10.05, 7.60, 10.13, and 7.42, MSE = 0.01, ps< .01,

.05 and .06, respectively. Jurors exposed to only negative PTP (N-PTP condition) made a greater number of negative PTP errors than jurors in the P-PTP, APN, BNP, and U-PTP conditions (see Table 2), Fs (1, 96 or 97) = 10.05, 7.60, 10.13, and 7.42, MSE = 0.01, ps< .01,  .03, .02, .03, .02; the difference between N-PTP jurors an ANP jurors approached statistical significance F(1, 96) = 3.45, p = .06,

.03, .02, .03, .02; the difference between N-PTP jurors an ANP jurors approached statistical significance F(1, 96) = 3.45, p = .06,  .02. Interestingly, with only one exception (BPN jurors) the mixed PTP jurors (BNP, ANP, and APN) did not significantly differ from the U-PTP jurors on critical N-PTP errors, Fs< 0.81, MSE = .01, ps > .36. The reduction in negative-PTP critical errors for the mixed-PTP conditions as compared to jurors in the N-PTP condition may be due mixed jurors reduced memory for the PTP. Specifically, jurors in the mixed-PTP conditions were consistently more likely than N-PTP jurors to misattribute negative-PTP facts to new (see Table 2), Fs> 26.00, MSE = .02, ps< .05. Given that there was less repetition of each PTP fact for the mixed jurors (hence fewer rehearsals), it makes sense that mixed jurors’ memory for these facts would less than that of N-PTP jurors.

.02. Interestingly, with only one exception (BPN jurors) the mixed PTP jurors (BNP, ANP, and APN) did not significantly differ from the U-PTP jurors on critical N-PTP errors, Fs< 0.81, MSE = .01, ps > .36. The reduction in negative-PTP critical errors for the mixed-PTP conditions as compared to jurors in the N-PTP condition may be due mixed jurors reduced memory for the PTP. Specifically, jurors in the mixed-PTP conditions were consistently more likely than N-PTP jurors to misattribute negative-PTP facts to new (see Table 2), Fs> 26.00, MSE = .02, ps< .05. Given that there was less repetition of each PTP fact for the mixed jurors (hence fewer rehearsals), it makes sense that mixed jurors’ memory for these facts would less than that of N-PTP jurors.

|

.001, and approached significance for the APN jurors (1, 96), F = 3.06, MSE = 0.02, p = .08. The blocked jurors did not significantly differ from P-PTP jurors in the proportion of positive PTP items attributed to new, Fs(1, 97) = 0.03 and 2.42, MSE = 0.02, ps> .12. Why we did not observe the similar proportions of new responses for blocked jurors is not clear given that both alternating and blocked received the same number of exposures to each fact.

.001, and approached significance for the APN jurors (1, 96), F = 3.06, MSE = 0.02, p = .08. The blocked jurors did not significantly differ from P-PTP jurors in the proportion of positive PTP items attributed to new, Fs(1, 97) = 0.03 and 2.42, MSE = 0.02, ps> .12. Why we did not observe the similar proportions of new responses for blocked jurors is not clear given that both alternating and blocked received the same number of exposures to each fact.3.5. Source Monitoring: Correct Trial Judgments

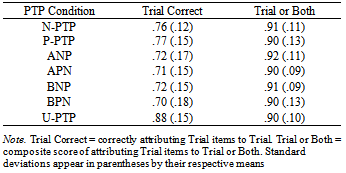

- In order to examine differences among groups in the proportion of correct source monitoring judgments for trial items, a one-variable (PTP exposure) between-subjects ANOVA was performed on trial items (corrected for guessing: the proportion of new items the participant identified as being in the trial was subtracted from the participant’s initial correct judgment score). There was a significant effect of PTP on correct trial judgments, F(6, 338) = 7.37, MSE = .02, p < .01,

.12. Jurors in the U-PTP condition accurately identified significantly more of the trial items as coming from the trial than jurors in the mixed and pure PTP conditions (see Table 3), Fs(1, 96 or 97) > 12.20, MSE = 0.02, ps< .01. The differences between U-PTP jurors’ correct trial judgments and those of PTP exposed jurors appears to due to exposed jurors attributing 15% to 20% of the trial-only items to both the trial and the PTP articles, compared with only 2% for U-PTP. When trial items attributed to trial and trial items attributed to both trial and PTP were combined, there was not a significant effect of PTP exposure on this composite score (see last column of Table 3), F(6, 339) = 0.92, MSE = 0.002 and 0.01, p = .48. This suggests that all jurors had good memory for the trial facts, but those exposed to PTP also believed that they read about a significant number of these facts during the PTP exposure phase of the experiment.

.12. Jurors in the U-PTP condition accurately identified significantly more of the trial items as coming from the trial than jurors in the mixed and pure PTP conditions (see Table 3), Fs(1, 96 or 97) > 12.20, MSE = 0.02, ps< .01. The differences between U-PTP jurors’ correct trial judgments and those of PTP exposed jurors appears to due to exposed jurors attributing 15% to 20% of the trial-only items to both the trial and the PTP articles, compared with only 2% for U-PTP. When trial items attributed to trial and trial items attributed to both trial and PTP were combined, there was not a significant effect of PTP exposure on this composite score (see last column of Table 3), F(6, 339) = 0.92, MSE = 0.002 and 0.01, p = .48. This suggests that all jurors had good memory for the trial facts, but those exposed to PTP also believed that they read about a significant number of these facts during the PTP exposure phase of the experiment.

|

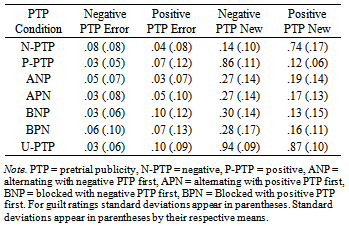

3.6. Hypothesis 5: Confidence in Source Memory Judgments

- The confidence scale for the source monitoring judgments ranged from 1 (not at all confident) to 7 (extremely confident). For critical SM errors, only jurors making these types of errors were included in these analyses and hence the degrees of freedom differ from analyses above. The N-PTP jurors indicated that they were significantly more confident in their negative-PTP critical errors than P-PTP, ANP, BNP, and U-PTP jurors (see Table 4), Fs(1, 52, 54, 52, and 45) =7.31,4.20, 3.90, and 4.89, MSE = 2.62, ps< .05, 2s= .03, .02, .02, and .02. Therefore, not only did the N-PTP jurors make more critical source monitoring errors than their P-PTP, ANP, BNP, and U-PTP counterparts, but they were also more confident when doing so. The U-PTP and mixed-PTP (blocked and alternating) jurors did not differ on their mean confidence ratings for negative-PTP critical errors, Fs< 3.47, MSE = 2.62, ps> .06.

|

.08, .01, .01, and .02. Therefore, although P-PTP jurors did not significantly differ from other jurors in the proportion of positive- PTP critical errors, when P-PTP jurors made these errors they were significantly more confident in them than jurors in the N-PTP, ANP, BPN, and U-PTP conditions. Additionally, N-PTP jurors were significantly less confident in their positive-PTP critical errors than ANP, APN, BNP, BPN, and U-PTP jurors (see Table 4), Fs(1, 58, 64, 72, 70, and 68) = 5.49, 8.20, 9.92, 7.05, and 4.67, MSE = 1.54, ps< .05,

.08, .01, .01, and .02. Therefore, although P-PTP jurors did not significantly differ from other jurors in the proportion of positive- PTP critical errors, when P-PTP jurors made these errors they were significantly more confident in them than jurors in the N-PTP, ANP, BPN, and U-PTP conditions. Additionally, N-PTP jurors were significantly less confident in their positive-PTP critical errors than ANP, APN, BNP, BPN, and U-PTP jurors (see Table 4), Fs(1, 58, 64, 72, 70, and 68) = 5.49, 8.20, 9.92, 7.05, and 4.67, MSE = 1.54, ps< .05,  .02, .03, .02, and .01 The U-PTP and mixed-PTP jurors did not significantly differ on their mean confidence ratings for positive-PTP critical errors, Fs< 0.86, MSE = 1.54, ps> .35.PTP exposure did not have a significant effect on jurors’ confidence in their correct trial judgments (trial items attributed to trial), with all PTP exposure groups indicating a high level of confidence in these judgments (see Table 4), F(6, 338) = 1.38, MSE = 0.45, p = .22.

.02, .03, .02, and .01 The U-PTP and mixed-PTP jurors did not significantly differ on their mean confidence ratings for positive-PTP critical errors, Fs< 0.86, MSE = 1.54, ps> .35.PTP exposure did not have a significant effect on jurors’ confidence in their correct trial judgments (trial items attributed to trial), with all PTP exposure groups indicating a high level of confidence in these judgments (see Table 4), F(6, 338) = 1.38, MSE = 0.45, p = .22.4. Discussion

- The research presented in this paper is only the second study to expose mock-jurors to PTP in a spaced fashion (over time). Typically in PTP research mock-jurors are exposed to PTP in a single session. Given that actual jurors are likely exposed to PTP over time, single session (mass) exposure to PTP is not ecologically valid. The first study to use the spaced-PTP exposure method was Ruva et al.[14]. The present study attempted to increase the ecological validity of Ruva and associates’ work by eliminating the predecisional distortion task after each PTP story. The predecisional distortion paradigm involves a multiple decision tasks that can affect the way people process information, especially how much attention is paid to information[15, 40]. Although how jurors’ decisions change over time is of interest to researchers and necessitates asking jurors to report about their decision along the way, actual jurors do not engage in predecisional distortiontasks. Therefore, during the PTP exposure phase, jurors in the present study were only asked to read a PTP story and answer six open-ended memory questions. Ruva and associates[14] found a primacy effect for jurors in the blocked conditions who read negative PTP first (BNP), but a leveling of PTP bias for blocked jurors who read positive PTP first (BPN). Similar to Ruva and associates we found a leveling of bias for BPN jurors, but contrary to their findings we also found a leveling of bias for BNP jurors. The difference in methodology explained above may be responsible for our failure to find a primacy effect for BNP in the present study. This is because the multiple task predecisional distortion procedure has been found to result primacy effects[20]. In the present study we found that regardless of the order (positive or negative story first) or type of presentation (blocked or alternating), jurors exposed to mixed-PTP had verdicts that most closely resembled U-PTP jurors. Therefore, mixed-PTP exposure either reduced or ameliorated the effect of PTP on verdicts. For the blocked jurors this amelioration of PTP bias held for the more sensitive measure of guilt ratings. This was not the case for the alternating jurors. Presenting conflicting PTP stories in an alternating fashion did lead to a reduction of PTP bias, as evidenced by alternating jurors’ verdict distributions closely resembling those of jurors U- PTP. That being said, for alternating jurors the effect of PTP bias guilt ratings was reduced, but it was not eliminated and the order that PTP was presented mattered. Specifically, it appears that a recency effect was at work for guilt ratings, with ANP jurors (whose last PTP story was positive) looking more like P-PTP jurors, and APN jurors (whose last story was negative) more closely resembling N-PTP jurors. Now we turn to how PTP exposure affected source memory. Overall, the critical SM errors in this study are lower than those in past studies[e.g., 5, 11]. This improved source memory performance may be due to the increase in temporal cues afforded by the spaced PTP procedure[32-34]. In addition, past studies have presented PTP and trial stimuli in similar settings or environments (laboratory). In the present study PTP was presented online (web) and the trial was presented in a laboratory setting. These additional environmental cues may have aided source discrimination [32, 33]. Clearly more research is needed to explore how both spacing and environmental cues influence source memory for trial and PTP information. Future research should explore both spacing and environmental cues effects on source memory. This could be done by having conditions in which the trial and PTP are both spaced over several days (which is typical for high profile trials), and hence eliminating the spacing cue. This condition could be compared to one in which both the PTP and trial are presented in in a single session.Also, of interest is the fact that the mixed-PTP jurors’ memory for PTP was less than that of pure-PTP jurors (N-PTP and P-PTP). This was evidenced by mixed-PTP jurors being more likely than pure-PTP jurors to indicate that PTP facts they were exposed to were new. This is most likely due to the fact that mixed jurors only received 4 stories for each type of PTP (4 negative and 4 positive), whereas pure jurors received 8 of the same type of stories. Pure-PTP jurors’ additional repetition/rehearsal of these PTP facts is most likely why they had superior memory for these facts. This can also explain why the mixed-PTP exposure jurors had fewer critical SM errors – they did not remember the facts and so did not misattribute them to trial or both, instead they misattributed them to new.

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

- The present research suffers from limitations typical of most mock-juror experiments. First, the trial we used was only 30 minutes in duration, whereas typical trials can last for days or weeks. Second, although we spaced PTP exposure out across approximately 10 days and had a week delay between the last PTP story and trial presentation, actual jurors are likely to be exposed to PTP in high profile cases over a longer period of time and may have a longer delay between PTP exposure and trial exposure. Third, our mock-jurors did not deliberate and so it is not clear how deliberation affects PTP bias of mixed-PTP vs. pure-PTP jurors. Finally, as mentioned above the generalizability of our results may be limited due to our mostly Caucasian sample of college students.Future research should attempt to improve upon the current methods by increasing ecological validity and perform generalizability studies. In order test for generalizability researchers should comparePTP effects in culturally diverse samples of jurors. To increase ecological validity, a longitudinal field study could be employed in which mock-jurors are naturally exposed to real PTP over the course of an actual case (e.g., from media coverage of arrest through pre-trial hearings). Finally, how jury deliberation affects PTP bias is definitely an area that is deserving of future exploration. For example does deliberation increase or reduce PTP bias.

5. Conclusions

- The research presented in this paper provides a second look at how spaced exposure to PTP and exposure to mixed PTP affects jurors’ decisions. Additionally it explored the effects of pure- vs. mixed-PTP exposure on jurors’ source memory. This research is timely given that we are beginning to see media savvy defense attorneys and defendants, knowing the influence media reports can have on prospective jurors, doing whatever it takes to get their stories out in hopes of leveling the playing field. Some have set up websites (e.g., George Zimmerman and Matthew David Stewart), used Face Book or Twitter, blogs, TV interviews, or found other ways to paint themselves in a positive light, or the victim in a negative one (e.g., photos or information). This has resulted in multiple types of PTP in some high profile cases, and could result in juries being made up of jurors with various types of PTP bias (pro-defense, pro-prosecution, mixed-PTP or no bias). The research presented here suggests that these conflicting PTP stories may reduce or even eliminate PTP’s biasing effects of jurors’ decisions, which is a promising outcome. Obviously more research is needed to see how various types and amounts of PTP can affect both juror- and jury-level decisions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors thank all of the research assistants that worked on this project – without their hard work and dedication to this project it would not have been completed. These research assistants are listed in alphabetical order:Christen Cirks, Sarah Fredrickson, Autumn Frei, Rachel Glover, Christina Guenther, Steven Hannen, Michael Hoban, Aliyah McGowan, Katherine Mitchell, Stephanie Smith, Meredith Velazquez, and Rachel Whitehead.

Appendix A: Pretrial Publicity Conditions

Appendix B: Sample of Items from the Negative PTP, Positive PTP, and Unrelated News Stories

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML