-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(1): 9-15

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140401.02

Relation between Depression, Family Support and Stress at Work in Undergraduates

Gisele Aparecida da Silva Alves1, Makilim Nunes Baptista2, Acácia Aparecida Angeli dos Sant2

1Masters’ Graduated at Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia from Universidade São Francisco (USF), Itatiba/SP

2Professor at Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia from Universidade São Francisco (USF), Itatiba/SP

Correspondence to: Gisele Aparecida da Silva Alves, Masters’ Graduated at Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia from Universidade São Francisco (USF), Itatiba/SP.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study aimed at seeking validity evidences based on the relation with other variables for Baptista Depression Scale – adult version (EBADEP-A), by correlating it to Perceived Family Support Inventory (IPSF) and Vulnerability to Stress at Work Scale (EVENT). 197 undergraduates, both genders, were participants. They aged between 18 and 65 years old (M = 23.44, SD = 6.83). The results indicated significant negative correlations between EBADEP-A and all dimensions of the IPSF, namely family adaptation, family autonomy and consistency-affectiveness, as well as the total score, and also positive correlations between EBADEP-A and 2 factors of EVENT, as well as the total score.

Keywords: Psychological assessment, Depressive symptoms, Family, Organizational environment, Validity

Cite this paper: Gisele Aparecida da Silva Alves, Makilim Nunes Baptista, Acácia Aparecida Angeli dos Sant, Relation between Depression, Family Support and Stress at Work in Undergraduates, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 9-15. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140401.02.

1. Introduction

- Depression symptoms have been classified as several kinds of alterations, including humor related (sad or depressed), psychomotor (agitation and retardation), cognitive (memory, attention and speed of thought and reasoning), neurovegetative (weight, sleep, sexual desire and somatic symptoms, such as muscle weakness, the sensation of weight on the back and cephalea), circadian rhythms (changes in sleep-wake patterns, cortisol levels and body temperature regulation) and seasonality (the pattern of recurrent depressive episodes at certain seasons)[22]. According to[17], the diagnosis of depression and the evaluation of the severity of symptoms are different tasks and both are important when monitoring the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Still according to these authors, professionals should pay attention to the presence, duration and course of depression symptoms.It is also important to highlight the clinically significant suffering or loss in affective, social and occupational areas caused by depression symptoms[3]. As much as diagnostic criteria such as DSM-IV[3] or CID-10[29] are indispensable for the evaluation of depression symptoms, depression scales also play an important role, taking into account their potential to help on patient monitoring and to base treatment results.Several studies highlight the role of psychosocial variables, along with biological variables, to explain the causes of depression, allowing diagnostic prediction for this disorder. ([12];[31]). Cognitive variables are among them, such as low resistance to frustration, irrational beliefs and low self-esteem[19]; and social variables, such as family characteristics and the presence of a supportive group of friends[10]. Those last two variables will be more detailed hereafter.The perceived support a person receives from the family seems to have an impact in many aspects of life, especially in the development of psychological disorders. According to[28], the primary socialization and first acquisition of norms for social behavior take place inside the family. Therefore, the perceived support from the family is so important it influences positively or negatively the way a person behaves[42].Considering the role family support seems to play in psychological disorders such as major depressive disorder,[7] discusses that the poor family support perception might favor the development of negative beliefs and undermine the learning of efficient and adequate coping strategies, especially with teenagers. Research offering empirical support to this assertion has been conducted. In the same direction, results obtained by[21], in a longitudinal study with 1322 adolescents aging from 12 to 19 years old, showed that depressive symptoms may be associated to age and low levels of satisfaction with family relations.On a revision study,[9] considered family support and family structure as risk factors for depression in teenagers. According to the authors, the specific cause for the development of depression cannot be always detected, since it is a multifactorial disorder. Nonetheless, sudden familiar or social changes (e,g., changes in composition, physical structure, rules and roles in the family) might contribute to the development and/or maintenance of depression among the adolescent population.[10]conducted a transversal correlational research study which assessed depression symptoms and family support in teenagers. The normative sample was composed by 154 high-school students attending public schools. The authors identified, as a result, a negative correlation between family support and depressive symptomatology, showing that the higher the levels of depressive symptoms in adolescents, the lower the perception of received family support. Especially in Brazil, few studies with young adults have been focusing on the relation between those constructs, as the present work intends to.Another important family function is to work as a shock absorber for stressful events faced by teenagers and young adults daily[9],[15]. In this context, family can help a person cope with stressful situations, acting also as a protective agent against mental diseases such as depression and optimizing the relations at work.Family and its members might constitute a valuable source of support or emotional breakdown. Similarly, the organizational environment, also with its members, might be a fundamental element of support or breakdown, even in relation to development and maintenance of mental diseases/disorders, including depression[18].About 60% of depressive episodes are preceded by stressing factors, mainly those with psychosocial origins. ([23];[36]). Although the term stress is highly propagated, there is no consensus about its definition[24]. Thus, it might be understood as threatening or defying stimuli to the organism, or even as an organic answer to threatening stimuli[27].[38] defined stress as a general adaptation syndrome, conceiving it as the result of a demand that is greater than the body could handle, leading to cognitive and somatic consequences.In an organizational environment, individuals could be exposed to factors that cause a certain amount of stress, leading to absenteeism, increase of rotation levels and work accidents, as well as a variety of diseases, such as depression[25]. Under this perspective,[41] consider workplace stress as the tension experienced at work as a product of the interaction between environmental factors, individual perception and behaviors, reflecting on the organization and on the workers’ mental health.Stress causes at work include function, role inside the organization, career development, work relations and organizational climate, organizational structure and the interface work-family. However, people have a personal and familiar history that might help them cope with weariness or weaken it[6]. In this sense,[4] conducted a study with undergraduates that looked for correlations between measures of perceived family support and vulnerability to stress at work. The results showed that the higher the perceived family support, the lower the scores for occupational stress. Still on the topic of the relation between mental health and occupational stress,[11] investigated the correlation between depression symptoms and vulnerability to stress in 121 undergraduates. The instruments are the same ones that were used on the present study, namely, the Baptista Depression Scale – adult version (EBADEP-A) and the Scale of vulnerability to stress at work (EVENT). Results showed positive and significant correlations between the two measures, suggesting that, the higher the frequency of depression symptoms, the higher the vulnerability to stress at work.Research such as that of[40] emphasize the environment as a stressful factor, highlighting the importance of family support. With the purpose of testing this hypothesis, authors studied 461 nurses of a public institution from Distrito Federal with average age of 53 years old, mostly females (87,2%) and married (57,8%). The results suggested that organizational environment and lack of family support were stressing factors.Literature has also been pointing to positive correlations between mental disorders, such as depression and stress with lack of family support.[35],[44]. Under this perspective,[43] conducted a transversal study with adolescents with ages ranging from 15 to 19 years old, exploring unbalanced relations between work/family and personal life, occupational stress and mental disorders. His findings showed that occupational stress and the lack of balance between work and family/personal life were independently associated to mood disorders, specifically depression, suggesting that both factors play an important role on the etiology of depression.Studies presented showed the importance of the aforementioned phenomena on people’s daily lives, nevertheless, there were no articles on Brazilian bibliographic databases approaching those three constructs simultaneously. Thereby, the purpose of this study was to explore relations between depression symptoms, perceived family support and vulnerability to stress at work.

2. Method

- Participants197 undergraduates attending private schools located in several cities in São Paulo state, of which 57,4% were Psychology students and 32,5% Nursing students. Age ranged from 17 to 59 years old. (M = 23.44, SD = 6.83 years old), mostly females (80.7%). 80.2% of participants were single, and 17.8% were married.InstrumentsIdentification QuestionnaireThis questionnaire was developed by the authors to collect socio-demographic data, such as age, gender, date of birth, and marital status. Participants also answered to a questionnaire developed by ANEP[5], in order to categorize social class. The identification questionnaire was composed by 11 questions (gender, marital status, schooling of the household, who lives with the participant, history of mental disease in the family, history of depression, history of psychiatric assessment, marital status of parents, current occupation and current members of nuclear family), and four opened questions (age, major in college, semester and number of people living with the participant).Baptista Depression Scale – adult version (EBADEP-A) [12]The EBADEP-A was built based on DSM-IV[3], CID-10 [30], cognitive therapy[14] and on behavioral therapy for depression[19]. It is a “screening” instrument for both psychiatric and non-psychiatric samples, based on 26 indicators: depressed mood, loss of pleasure, weeping, hopelessness/lack of future perspectives, among others. For each of those indicators, sentences were created to represent extremes, so the participant, using a scale, indicates how he feels about that item. The instrument has 75 items and a 5-point Likert scale, used by participants to indicate how they feel about those given situations. The minimum possible score is 0 and the maximum is 300.Perceived Family Support Inventory (IPSF)[8]The IPSF measures a person’s perception of the support given by the family. It is a three-point Likert scale, using always, sometimes and never, with 42 items. The factorial analysis made with 1064 participants has yielded three dimensions, named here with their respective alpha coefficients: Affective-consistent (alpha = 0.91), composed by 21 items referring to affective expression among family members (verbal and non-verbal), among other manifestations. Family adaptation (alpha = 0.90), composed by 13 items about negative feelings and behaviors about family, such as anger, isolation, incomprehension, aggressive relations (quarrels and yelling), among others. Thus, the items in this factor must be inverted to present the same valence as the items in the other two dimensions. The last one is called Family autonomy (alpha = 0,78), with eight items about confidence, freedom and privacy between family members. The minimum possible score is 0 and the maximum is 84.Vulnerability to Stress at Work Scale (EVENT)[39]The EVENT evaluates the vulnerability to stressors in the workplace, involving the individual’s perception of the organizational institution, the company’s philosophy, work relationships and feelings of the employee, such as motivation or autonomy at work activities. It is a three-point Likert scale (never, sometimes and frequently). The scale has 40 items and three dimensions, namely, Organizational Climate and Functioning (alpha = 0.88), referring to inadequate physical environment, unprepared headship, excessive expectations from superiors, among others. Work pressure (alpha = 0.85) includes aspects such as the accumulation of work and functions, performing work that does not belong to function, excess of duties on everyday work, and so on. Infrastructure and Routine (alpha = 0.77), with items about double work journeys, poor equipment, frequent changes at work schedule and others. The total score is the sum of all marked items. Minimum score is 0 and maximum score is 80.ProcedureAfter the approval of this project by the Research Ethics Committee, and the authorization by IES - Instituições Superiores de Ensino, subjects agreed to participate by signing a term with information about the research. Instruments were answered in group, in the following order: to 50% of the subjects, Identification questionnaire, EBADEP-A, IPSF and EVENT. The other 50% answered to the identification questionnaire, EBADEP-A, EVENT and IPSF, as an attempt to control respondent fatigue. The data collection took about 50 minutes.

3. Results

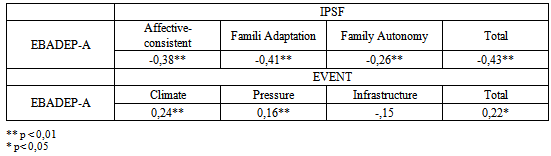

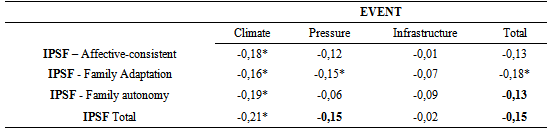

- Data were inserted and processed with SPSS 15, with a 5% significance level. First, descriptive analysis were used to define minimum score, maximum score, means and standard deviation found on sample, in order to compare those values to the normative data presented on the manuals of both instruments, namely, the IPSF and the EVENT, as follows.The average score in the EVENT was 32,14, and the standard deviation was 14,51. The minimum total score at the EVENT was 0, and the maximum total score was 64, within a range from 0 to 80 points. Regarding factorial scores in the EVENT, the factor Organizational Climate and Functioning yielded a 13,19 mean (compared to 14,47 in the normative sample), standard deviation of 7,35 (compared to 7,18 in the normative sample), with a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 32, also endorsing normative data found in the manual). The factor Work Pressure yielded a 13,39 mean (compared to 14,17 in the manual), standard deviation of 6,33 (compared to 5,60 in the manual), minimum score of 0 and maximum of 26, also endorsing normative data found in the manual. The third factor in the EVENT, named Infrastructure and Routine, yielded a 5,81 mean (compared to 6,51 in the normative sample), with a standard deviation of 4,01 (compared to 4,13 in the normative sample), minimum score of 0, endorsing normative data in the manual, and maximum score of 17 (compared to 21 in the normative sample).The mean score in the IPSF was 61,19 (compared to 61,17 in the normative sample) and the standard deviation was 8,45. Minimum score was 23 and maximum was 84, compared to 12 and 84 in the manual, respectively. With regard to factorial scores, the dimension Affective-consistent yielded a 27,60 mean score (compared to 27,64 in the normative sample), and the standard deviation was 8,45 (compared to 8,64 in the normative sample), minimum score was 3 (compared to 2 in the normative sample) and maximum score was 42, confirming normative data from the manual. Concerning to the factor Family Adaptation, the mean score yielded was 21,05 (compared to 21,21 in the normative sample), the standard deviation was 4,17 (compared to 4,22 in the normative sample), minimum score was 8 (compared to 0 in the normative sample) and maximum score was 26, exactly the same as in the manual. The factor named Family Autonomy presented mean of 12,56 (compared to 12,31 in the normative sample), standard deviation was 2,86 (compared to 3,12 from the normative sample), minimum score of 4 (compared to 1 in the normative sample) and maximum score of 16 (compared to 16 from the normative sample).Pearson’s correlation test was used to evaluate correlation between the EBADEP-A scores and the other two instruments. Obtained data are shown in Table 1.

|

|

4. Discussion

- The main objective of this study was to characterize young adults with respect to depression symptoms, perceived family support and vulnerability to stress at work, using the EBADEP-A, the IPSF and the EVENT. Results display negative correlations between the EBADEP-A and all IPSF dimensions, including total score. Thereby, the higher the scores for depression symptoms, the lower the scores for the instrument that measures perceived family support, confirming data found in literature[10],[37].A person’s behavior can be positively or negatively influenced by previous experiences within family. Thus, the perceived family support would play an important role in the way an individual evaluates the environment, and this evaluation could be adapted or not. Therefore, negativistic evaluations would tend to raise the probability of mental disorders such as depression[42]. Nevertheless, in the same way, someone presenting depressive symptoms could also distort negatively their perception of the support received from their family, since depressive patients often have negative thoughts about themselves, others and the world surrounding them. This pattern of negative thoughts presented in depression was described as Beck’s cognitive triad of depression[42]. [10] also found negative correlations between depression and perceived family support among teenagers, emphasizing that such relations also occur at older ages and explaining that family offers the first social environment, and so contributes to the way the environment is evaluated by a person. Therefore, negative patterns of social relationship and non-adaptative cognitive factors could be created, favoring the emergence of depressive symptomatology.The correlations with IPSF dimensions suggested that the higher the perceived interest, affection, attention, inclusion, dialogue, comprehension, clear family roles and rules, independence and problem solving abilities, the lower the depressive symptomatology presented by participants of this research.[26] found similar data, indicating poor displays of affection and overprotection of parents as a risk for depression. Data found in this research, therefore, are consistent with the findings of those authors. When it comes to overprotection, according to[32] and[33], depression is generated by the discouragement from parents to their children independency when facing stressing situations. In the same year,[32] and[33]also found evidence in one of their studies, in which depressive and manic depressive patients reported poor parental care and pronounced maternal overprotection.In regard to the negative correlations found in this research between the EBADEP-A and IPSF’s dimension Family Adaptation, the more positive feelings about family, comprehension and inclusion, the less depressive symptoms. According to[32] and[33], empathic parents would allow their children to develop more self-esteem, and this would be a protective factor against adult depression.As well as in the present research,[10] also found negative correlations between family support and depressive symptoms. Also, in a research conducted by Luecken (2000), subjects who had lost one of their parents presented more intense depressive symptoms and less social support when they had poor family relations. It can also be mentioned the meta analysis conducted by[34], that found that the depressive group was considered significantly more prevalent, when related to the loss of one of the parents in childhood, and the study conducted by[13], that found negative and significant correlations, suggesting that the more intense the depressive symptomatology, the worse the perception of family support.[9] understand family as a shock absorber for stress, and the same logic is used here. Therefore, family relations and their benefits, such as perceived family support, would work as shock absorbers for stressing factors that individuals face throughout life.[1] report that the accumulation of professional and family roles causes young adults to experience stress in a more intense way.Of all correlations between the EBADEP-A and the EVENT’s dimensions, the only dimension that did not present significative correlations was Organizational Infrastructure. Thus, the results between the EBADEP-A and EVENT’s dimensions Organizational Climate and Functions and Work Pressure point out to a positive association, in that, the higher the scores on those dimensions, also the higher the scores for depressive symptoms.[18] discussed the stress at work as an environmental factor that leads to a predisposition of development and maintenance of diseases/disorders such as depression. The author argues that, besides the use of physical strength and tasks involving the risk of injures (depending of the function), nowadays, workers are expected to perform tasks that demand higher levels of mental concentration and other psychological factors, also leading to more mental fatigue. Thereby, workers would be subjected to more stressing work environments, characterized by downsizing, company restructuring, shorter deadlines and higher goals established by headship.[20] also discuss that stressing work conditions, when prolonged and intense, could trigger psychological and biological depressive tendencies, with correlations of r = 0,24 between the EBADEP-A and EVENT’s dimensions that evaluates situations of inadequate physical environment, problems with headship, authority, wages and work ascension, and of r = 0.16 between the EBADEP-A and the dimension that covers excess of responsibility, fast pace, among others.It is worth mentioning that results found in this study showed positive correlations between scores in the EBADEP-A and the EVENT for undergraduates. Therefore, the results confirm the findings of[11] and[16] that analyzed the association between those constructs in a sample of undergraduates.When it comes to correlations between perceived family support and vulnerability to stress at work, these results demonstrate that all IPSF dimensions were correlated to EVENT’s dimension Organizational Climate, but Family Adaptation was the only dimension to present a significant correlation to Pressure and to the total score. There was no significant correlation between IPSF’s dimensions and EVENT’s Organizational Infrastructure.[4] conducted a study with undergraduates and found similar results, confirming the present findings, using the same instruments used here, namely, IPSF and EVENT. The relation between constructs is negative, so that the higher the perceived family support, the lower the vulnerability to stress at work.

5. Conclusions

- The results obtained in this study have reached the purpose of this study, with respect to the frequency of depression symptoms, perceived family support and vulnerability to stress at work for working undergraduates. Additionally, the association between the constructs was identified as expected, both theoretically and empirically. Thus, a negative correlation was verified between depression and perceived family support, and a positive correlation was verified between depression and vulnerability to stress at work. There was also a negative correlation between the last two constructs, as expected.Some limitations to the results were considered, such as the narrow sample and the low variability of sex distribution, since the subjects were predominantly female and from a single state of the country. Therefore, it is suggested that more studies are conducted to explore more widely the relations between the constructs focused here, so that there is a greater possibility of generalization of the results by accumulation of information obtained from scientific researches. In addition, the sample of the present study was conveniently chosen, since the purpose of the study was to explore possible relations between constructs in undergraduates regardless of their academic background, and age. Hence, if found relevant, further studies should be performed aiming at these variables so that possible influences they might have in the way individuals perceive family support, present depressive symptomatology, and feel vulnerable to stress at work are possible to be investigated. Moreover, it is also suggested that depression should be compared to other related variables, such as coping strategies, suicide, anxiety, hopelessness, among others, including socio-demographic variables, such as socio-economic level, marital status, ethnicity and schooling.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML