-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2014; 4(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140401.01

Individual Differences in OCB: The Contributions of Organizational Commitment and Individualism / Collectivism

Marcia A. Finkelstein

Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, Tampa, 33620, United States

Correspondence to: Marcia A. Finkelstein, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, Tampa, 33620, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present study examined the relationships between organizational commitment and individualism/ collectivism and their respective relationships with organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and its motives. The findings bolstered earlier evidence linking OCB to a collectivist perspective. Collectivism also correlated more strongly than individualism with other-oriented motives for citizenship (i.e., concern for co-workers or the organization). Both collectivism and OCB were associated with normative commitment, one’s perceived responsibility to the organization, as well as to an emotional attachment as measured by affective commitment. The results provide new evidenced of dispositional factors, and their interaction with organizational variables, as contributing to OCB.

Keywords: OCB, Individualism/Collectivism, Organizational Commitment

Cite this paper: Marcia A. Finkelstein, Individual Differences in OCB: The Contributions of Organizational Commitment and Individualism / Collectivism, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20140401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The present study examined the relationships between organizational commitment and individualism/collectivism and the influence of these variables on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and its motives. The work built on prior investigations of the factors that initiate and sustain OCB.OCB represents a form of prosocial behavior, actions aimed at improving or maintaining the well-being of others[6]. Early research on prosocial behavior focused on spontaneous helping in emergencies[27]. More recently, behavioral scientists have turned their attention to ongoing, non-obligated service. One form of sustained activity that has garnered much of this attention is OCB[39]. The term refers to employee activities that exceed the formal job requirements and contribute to the effective functioning of the organization[37]. Borman, Penner, Allen & Motowidlo[5] postulated that so-called “citizenship performance” contributes to organizational effectiveness because it serves to create the psychological, social and organizational context necessary to carry out the formal responsibilities of the job. Citizenship behavior lubricates the social machinery of the workplace, increasing efficiency and reducing friction among employees[14, 42]. References to contextual performance or prosocial organizational behavior[3,4,6] emphasized the voluntary nature of these activities and distinguished them from task performance or one’s assigned duties[17,21]. The literature offers diverse ways of measuring OCB[29]. One popular conceptualization proposes two dimensions differentiated according to the intended beneficiary[14,21]. OCBI comprises citizenship that targets specific people and/or groups within the organization, while OCBO is service that directly benefits the organization. Examples of each include assisting others with work-related problems (OCBI) and offering ideas to improve the functioning of the organization (OCBO).The present study examined the contributions to OCB of motive, individualist / collectivist orientation, and organizational commitment. Prior work in our laboratory [19,20] supported a conceptual model that associates OCB with collectivist individuals who view citizenship behavior as part of the job and are motivated primarily by regard for co-workers. Individualists who engaged in OCB were motivated by concern for the organization per se. Individualism and collectivism were positively correlated, suggesting that they serve complementary functions. Which trait predominates at any given time may depend on which citizenship behavior is needed at that time.

1.1. OCB Motives

- Existing conceptual models of OCB[11,17,21,39, 40] hold that people perform citizenship behaviors for disparate reasons, with the same activity serving different psychological functions for different individuals. Rioux and Penner[31] identified three classes of motives for OCB. Two are relatively altruistic: organizational concern (OC) or respect for organization and a sense of pride and commitment to it; and prosocial values (PV), the desire to help others and be accepted by them. In contrast, impression management (IM) motives are egoistic. They involve a desire to be perceived as friendly or helpful in order to obtain specific benefits. Rioux and Penner[40] and Finkelstein and colleagues found that OCBI was most strongly associated with PV motives and OCBO with OC motives. Also correlated with PV motives was a collectivist orientation, while individualism was associated more with a commitment to the well-being of the institution (OC motives).

1.2. Individualism/Collectivism

- Initially individualism and collectivism were cultural distinctions[23]. In collectivist societies, members define themselves in terms of their group membership, and the well-being of the whole takes precedence over individual desires and pursuits. Individualist cultures draw sharper boundaries between the self and others, emphasizing personal autonomy and responsibility rather than group identification. At the societal level, individualism and collectivism typically are viewed as mutually exclusive, opposite ends of a bipolar scale.The constructs have been adapted to the individual and conceptualized as akin to personality traits[44]. The individualist perspective focuses on independence and self-fulfilment[38], on personal goals over group goals[46] and personal attitudes over group norms[41,45]. Collectivists are more likely to submerge personal goals for the good of the whole and to maintain relationships with the group even when the personal cost exceeds the rewards. Collectivism has been associated with both OCBO and OCB[20]. Employees holding collectivistic values or norms were more likely to perform OCB and engage in cooperative behaviors[36,46]. Collectivism was related to OCB measured six months later[15] and also to a specific citizenship activity, serving as a mentor[5]. Finkelstein[19] reported that individualism and collectivism were positively related, suggesting that these seemingly opposing attributes are complementary; which of these traits predominates may depend on which citizenship behavior is needed at a given time. Overall, the findings suggested that it is not in amount of citizenship that individualists and collectivists differ, but in why they serve and how they perceive the experience.

1.3. Organizational Commitment

- Employees who perform OCB are particularly important in the current economic climate as organizations downsize and workers assume extra duties. Unemployment in the United States stands at 7.3%[7], making OCB essential to the operation of many institutions.Identifying the most committed employees, and understanding the basis for their commitment, may aid in predicting who is most likely to engage in citizenship activities. Organizational commitment refers to an employee’s identification with, and involvement in, the organization. Commitment encompasses a belief in the organization’s values and mission, a willingness to put forth substantial effort on its behalf and the desire to remain part of the organization[43].Allen & Meyer[1] proposed that organizational commitment comprises three components. Affective commitment is one’s attachment to, and positive feelings for, the organization. Attachment based on the perceived costs of leaving the organization is known as continuance commitment, while normative commitment is defined as feelings of obligation to remain. The three tap what the employees wants, needs, and believes he or she should do, respectively.Affective commitment correlates positively with positive employee outcomes including job performance[34], reduced turnover[33], the desire to remain with the organization[32] and involvement in its activities. The increased involvement extends to OCB[22]. Affective and normative commitment both are associated with collectivism. This finding likely results from the collectivist emphasis on interdependence and norms that emphasize group identity[9,26]. Consistent with the individualist’s emphasis on preserving personal gains and avoiding negative outcomes, continuance commitment has been shown to correlate with individualism.

1.4. Hypotheses

- The first set of hypotheses addressed the relationship between individualism / collectivism and organizational commitment. They derive from the supposition that who define themselves in terms of group membership, and for whom group needs take precedence, feel greater obligation and attachment to the organization.

1.4.1. Hypothesis

- 1a. Collectivism will show a stronger relationship than individualism with normative commitment.1b. Collectivism will correlate more strongly than individualism with affective commitment. We did not predict any systematic differences between individualisms and collectivism with regard to continuance commitment. There is no reason to expect that either group would be more concerned about the costs of leaving the organization.

1.4.2. Hypothesis

- The next hypothesis addressed the association between organizational commitment and OCB motives. We expected regard for the organization and its employees to increase attachment to it and perceived responsibility for its well-being.2. OC and PV motives will correlate positively with both affective and normative commitment. The strength of these associations will be greater than that between IM motives and either type of organizational commitment. No predictions were offered with respect to continuance commitment and motive.

1.4.3. Hypothesis

- Hypothesis 3 tackled organizational commitment and OCB. Affectively committed employees are more involved in organizational activities therefore likely to perform OCBs more frequently than those who are less committed. Normative obligations, too, will push individuals to do more than the job description mandates[24]. 3. Affective and normative commitment will be positively related to OCB. Both relationships will be stronger than that between OCB and continuance commitment.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- Participants were 140 undergraduates (103 female and 37 male) at a metropolitan university in the southeastern United States. They worked for a variety of organizations, all at their current place of employment for at least six months. Most (n = 116 or 83%) had been with their present employer 12 months or longer and worked between 1 and 10 hours per week (n = 80 or 57%). Respondents completed questionnaires in exchange for extra course credit. The questionnaires were administered online through the psychology department’s participant pool management software, and participants’ identities were not shared with the investigator. No specific recruitment strategies were employed. All students enrolled in psychology classes that credit offered for participation were free to choose among any of the available studies.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

- Self-reported OCB was measured with Lee and Allen’s[28] scale. The instrument assesses OCBO and OCBI by listing examples of citizenship behavior and asking participants how often they engage in each. The scale comprises 16 items, eight corresponding to OCBO (e.g., “Offer ideas to improve the functioning of the organization”) and eight to OCBI (e.g., “Help others who have been absent”). Respondents indicated from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always) how often they engaged in each behavior. The coefficient alphas for each factor were .84 (OCBI) and .88 (OCBO).

2.2.2. OCB Motives

- The Citizenship Motives Scale[40] assessed Prosocial Values and Organizational Concern motives for OCB. Ten items assess Organizational Concern motives (e.g., “Because I want to understand how the organization works”); 10 measure Prosocial Values motives (e.g., “Because I want to help my co-workers in any way I can”) and 10, Impression Management motives (e.g., “To look like I am busy”). Participants rated each on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all important) to 5 (Extremely important). A modified 10-item scale[20] was used to measure Impression Management motives. Cronbach’s alpha for the three motives subscales was .86 (PV), .93 (OC), and .86 (IM).

2.2.3. Individualism/Collectivism

- The construct was measured with the scale developed by Singelis et al.[41]. The instrument contained 27 items, 13 assessing individualism (e.g., “Being a unique individual is important to me”) and 14, collectivism (e.g., “I feel good when I cooperate with others”). The 5-point rating scale has alternatives ranging Strongly disagree to Strongly agree. Coefficient alphas calculated from the present data were .62 for individualism and .84 for collectivism. While alpha for individualism was somewhat low, the correlations with OCB and OCB motives replicate those obtained in prior studies[12, 20].

2.2.4. Organizational Commitment

- Affective, normative, and continuance commitment (8 items each) were assessed with the instrument by Allen & Meyer[1]. Examples of each include “I think that people these days move from company to company too often” (normative), “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization” (affective), and “Too much in my life would be disrupted if I decided I wanted to leave my organization now” (continuance). For each subscale respondents indicated on a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly disagree to Strongly agree) the extent to which each item described them. Reliability coefficients were .84 (affective commitment), .68 (normative commitment), and .66 (continuance commitment).

3. Results

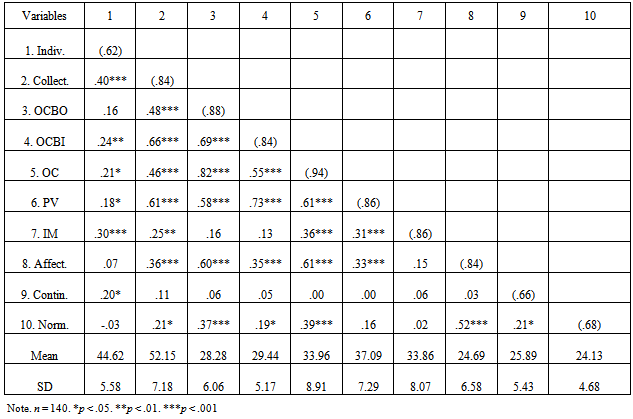

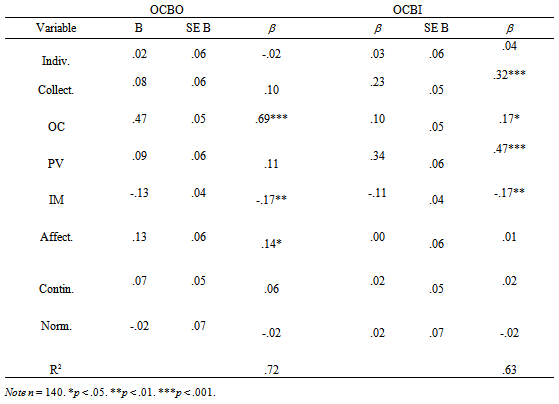

- Table 1 presents the correlations among the variables along with their means, standard deviations, and coefficient alphas. The results and discussion are organized around the three hypotheses. In the analyses, each dimension of OCB (OCBI or person-oriented behaviors and OCBO or organization-focused behaviors) is considered separately. The first hypothesis linked collectivism to organizational commitment and was supported by the data. Collectivism, as anticipated, was more strongly associated than individualism with both normative (r = .21 vs. r = -.03, t(137) = 2.62, p < .01) and affective commitment (r = .36 vs. r = .07, t(137) = 3.30, p < .01). There was no difference between individualism and collectivism with regard to thee strength of relationship with continuance commitment (r = .11 for collectivism, r = .20 for individualism, t(137) = 0.91, ns.). Hypothesis 2 predicted that both affective and normative commitment would show a stronger association with OC and PV motives than with IM motives. The data largely supported the hypothesis. OC motives were positively related to affective and normative commitment, r = .61 and r = .39, respectively; the association with affective commitment was significantly stronger, t(137) = 3.30, p < .01. PV motives were significantly associated with affective (r = .33) but not normative commitment (r = .16), and the difference was significant [t(137) = 2.13, p < .05].Neither affective nor normative commitment showed a significant correlation with IM motives, r = .15 and r = .02, respectively. The association between affective commitment and IM motives was significantly weaker than the affective-PV [t(137) = 1.88, p < .05] and affective-OC relationships [t(137) = 5.97, p < .01]. While the normative commitment-IM motives correlation was weaker than the normative-OC connection [t(137) = 4.15, p < .01], there was no significant difference between normative commitment- PV motives and normative-IM motives, t(137) = 1.40, ns.With regard to Hypothesis 3, the results fit the predictions. Affective commitment correlated significantly with both OCBO (r = .60) and OCBI (r = .35). The relationship was OCBO was stronger, t(137) = 4.62, p < .01. Normative commitment, too was more strongly related to OCBO (r = .37 vs. r = .19 for OCBI); the difference was significant, t(137) = 2.86, p < .01. Continuance commitment showed no significant association with either type of citizenship behavior (r = .06 for both). The affective-OCBO and affective-OCBI relationships were significantly stronger than the corresponding relationships for continuance commitment and OCB[t(137) = 5.62, p < .01 and t(137) = 2.58, p < .01]. A similar pattern was found for normative relative to continuance commitment. The normative-OCBO correlation was significantly stronger than continuance- OCBO, t(137) = 3.07, p < .01. However, the relationship between normative commitment and OCBI was not stronger than that between continuance commitment and OCBI, t(137) = 1.22, ns.Examining the relationship between individualism/ collectivism and OCB motives revealed that collectivism significantly correlated with all three. For PV motives, r = .61; for OC, r = .46; and for IV motives, r = .25. The relationship with PV motives was greatest; for collectivism-PV motives v. collectivism-OC motives, t(137) = 2.50, p < .05. Additionally, OC correlated with collectivism more strongly than did IM motives, t(137) = 2.43, p < .05.Individualism also correlated significantly with all motives (r = .30 for IM, r = .21 for OC, and r = .18 for PV). However, there was no difference among the three motives in the strength of their relationships with individualism. (For individualism-IM v. individualism-PV motives, t(137) = 1.25, ns.). Table 1 revealed large intercorrelations among variables, including OCBO and OCBI. To examine the separate contributions of motive, individualism/collectivism, and organizational commitment to each type of citizenship behavior, regression equations were calculated. All variables were simultaneously entered as predictors of OCBO and OCBI, respectively. Table 2 shows the results.

|

|

4. Discussion

- The present findings add to earlier evidence linking OCB to a collectivist perspective. OCBO and especially OCBI were more strongly associated with collectivism than individualism. The collectivism-OCBI relationship likely derives from the collectivist emphasis on group membership. OCBO is directed at the organization as a whole, and such broad-based service may be somewhat less compelling to collectivists (though the collectivism-OCBO correlation was significant.) Indeed, collectivists often limit their assistance to in-group members[2,16]. We have begun a study investigating whether collectivists target their OCBI to specific subsets of individuals within the organization. Collectivism also correlated more strongly than individualism with other-oriented motives for citizenship. This held for both concern for the individual (PV motives) and the organization (OC motives)[see also 12,19]. Collectivism also was more closely associated with a perceived responsibility to the organization as measured by normative commitment. Such obligation is expected from those who place group needs over individual desires [41,45,46]. Volunteer data also show that for collectivists, social norms are an important antecedent to service[24,47]. Communalism, an individual’s orientation toward social obligation and interdependence, predicted time spent volunteering[31].Collectivism correlated significantly with normative and affective commitment. The relationships suggest that with a collectivist orientation comes a perceived duty to support co-workers and an emotional attachment to them. Both types of commitment in turn were associated with OCB. The results for organizational commitment mirror findings obtained at the cultural level: Both affective and normative commitment are greater in countries with stronger collectivist orientations, while continuance commitment is unrelated to individualism/collectivism[35]. In the present study, too, continuance commitment was unrelated to collectivism and bore no relationship to OCB. That potential costs associated with leaving were not a consideration is consistent with the lack of any relationship between self-focused IM motives and OCB. The results corroborate earlier findings that although people help for myriad reasons, selfish motives tend to be less important than other-oriented objectives[17,21,40]. Dávila & Finkelstein[13] found that IM motives were associated with negative affect. Perhaps tackling extra tasks in hopes of personal gain generates anxiety or hostility, stemming in part from the awareness that one is less altruistic than is socially desirable. According to self-determination theory, when behaviors have an external locus of causality rather than being rooted in personal values, autonomy is undermined. This in turn reduces feelings of well-being [48]. The regression analyses showed that collectivism and PV motives and, to a lesser extent, OC motives, best predicted OCBI. Feeling connected to, and concerned for, the group offers a powerful incentive to help others; regard for the organization also provides an inducement. OC motives were the greatest determinant of OCBO, with affective commitment also playing a significant role. Affective commitment may mediate the relationship between one’s identity as a member of an organization and OCB[30].

4.1. Study Limitations/Future Directions

- The participants, although relatively long-term employees, also were college students. Every aspect of work life, including motives for engaging in citizenship, attachment to the organization, and costs associated with leaving, evolves over time. Certainly personal variables, such as family obligations, will influence the relationships studied here[18].In addition, we did not ascertain the types of jobs held or the nature of the companies employing them, thus limiting our ability to generalize our results. A complete understanding of the factors that underlie OCB needs to consider workplace factors and the interaction between the individual and the organization. That our OCB measure examined the target of citizenship behavior potentially affected our findings. Some scales take a different approach and utilize such categories as altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy and civic virtue[37]. Still others examine interpersonal helping, individual initiative, and industriousness and the extent to which one defends and promotes the organization[36]. Relationships among variables may depend in part on the instrument used. Finally, the present work relied solely on self-reports of OCB. Though some accuracy may be sacrificed, our interest was less in an objective accounting of helping than in people’s perceptions of their behavior and its influences. Future work with a more diverse sample of employees will address questions of causality. For example, OCB motives may drive citizenship behaviors and also be changed by such activities. Similarly, affective attachment to the organization can be influenced by OCB as well as influencing it. We also will examine whether collectivists limit OCBI to a particular subset or “in-group” of co-workers. In summary, the findings provide new evidenced of dispositional variables, and organizational-dispositional interactions, as contributing to OCB. Companies seeking staff who are willing to do extra would benefit from employees who are invested in the organization rather than those focused on personal advancement. The observed relationship between collectivism and citizenship behavior corresponds to that between collectivism and other prosocial activities, particularly volunteerism. The results also provide additional support for the utility of a conceptual model that includes organizational commitment in the prediction of OCB.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML