Yukiko Mochizuki1, Emiko Tanaka2, Etsuko Tomisaki1, Taeko Watanabe1, Kentaro Tokutake1, Bailiang Wu1, Misako Matsumoto1, Chihiro Sugita1, Amarsanaa Gan-Yadam1, Tokinari Matsui3, Chihiro Tada4, Tokie Anme1

1Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan

2Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Research Fellowship for Young Scientists), Tokyo, Japan

3Gifu Prefectural Academy of Forest Science and Culture, Gifu, Japan

4Tokyo Toy Museum, Tokyo, Japan

Correspondence to: Yukiko Mochizuki, Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The objectives of the study are to assess the chronological effects of - “Mokuiku” (-wood education) - in a nursery school using drawings done by children and their caregivers before and after participating in wood education and to serve as an aid in supporting child rearing. The subjects comprised 168 nursery school children and their caregivers in the Japanese M City. We conducted two-hour each sessions twice a year from 2010 to 2012. The participants were asked to draw pictures of trees before and after each session. We followed up for three years on the changes that occurred in the drawings made by 56 children and their caregivers. We used the number of colors, items,and sizes in the drawings, and their impression for analysis. Then, to verify the chronological effects of wood education, we compared two groups’ drawings between a 2010 pre-wood education control group and a group of 56 children who participated in all sessions. For all six sessions, the all categories were greater after the session than before; significant differences were observed in one or more categories. To verify the chronological effects of wood education, significant differences were observed between the control group and the all-sessions group in the number of colors and items. The positive effects of wood education were demonstrated by the increase in the all categories of their drawings. The continuous application of wood education may thus support child development.

Keywords:

Mokuiku (Wood Education), Nursery School, Drawings, Nursery School Profession, Childcare Support

Cite this paper: Yukiko Mochizuki, Emiko Tanaka, Etsuko Tomisaki, Taeko Watanabe, Kentaro Tokutake, Bailiang Wu, Misako Matsumoto, Chihiro Sugita, Amarsanaa Gan-Yadam, Tokinari Matsui, Chihiro Tada, Tokie Anme, Effects of Wood Education in a Nursery School with a Focus on Changes in Children and Caregivers’ Drawings, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 145-150. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130306.01.

1. Introduction

Wood education is an endeavor in which people come into contact with wood, learn from it, and live with it, with the aim of fostering “rich hearts” that actively consider people’s relationship with wood and forests. The introduction of wood education into nursery schools is considered to promote children’s physical, emotional, and social development. .So far practical program development and staff training was promoted[1-3]. However, few studies have examined the effects of wood education on children and their caregivers using Drawings [4]. It is thus urgent to provide professionals with the expertise to support child development and childcare practices by using scientific evidence to assess the effects of wood education in childcare centers.The objectives of the present study are as follows: to assess the chronological effects of wood education in a nursery school using drawings done by children and their caregivers before and after participating in wood education; to provide professionals with the expertise to support child development and childcare practices; and to serve as an aid in supporting the development and raising of healthy children.

2. Study Methods

In order to verify the chronological effects of wood education, we studied 168 nursery school children and their caregivers in the provincial Japanese town of M City. We conducted two-hour wood education sessions twice a year in 2010, 2011, and 2012 (six sessions in total). Children and their caregivers were asked to draw pictures of trees before and after each session following the simple instruction, “Please draw a picture of a tree.” The pictures were drawn using crayons. For three years, we followed up the changes found in the drawings made by a group of 56 children (aged 3–4 years in 2010) and their caregivers. In order to verify the chronological effects of wood education, we compared the number of colors used in the drawings, their sizes, and the number of items before and after the program. We excluded any cases that did not include a full set of drawings made before and after the program. Cases in which the child’s drawing was considered to be the work of the caregiver were also excluded.In order to assess the chronological changes in the children and caregivers’ drawings, the mean, median, and 25th and 75th percentile values were calculated for the number of colors, items, and size of the drawing before and after each of the six sessions. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was then used to calculate any significantbetween-group differences based on the differences in number of colors, items, and sizes of the drawings before and after each session.In order to verify the chronological effects of wood education while accounting for child development, Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test was used to calculate any significant differences between a 2010 pre-wood education control group (comprising 10 children aged 5–6 years before the first wood education session) and a group of 56 older children who participated in all six sessions (hereafter, the “all-sessions group”). The two groups were compared in terms of the number of colors, items, and size of the drawings.

3. Results

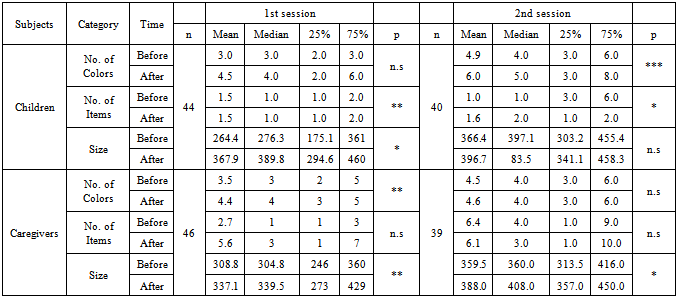

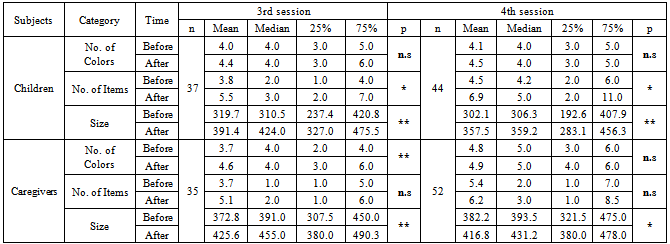

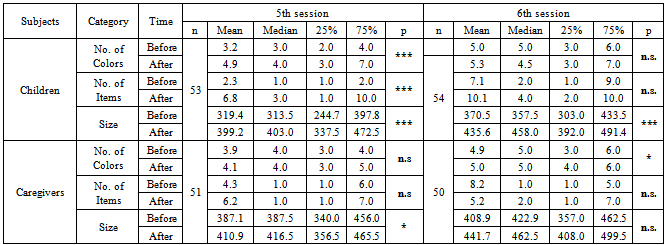

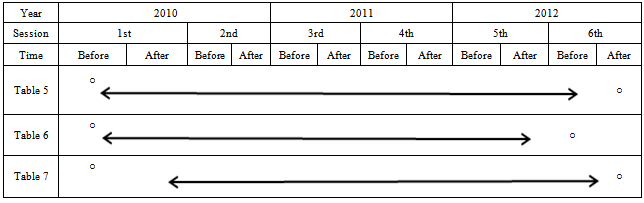

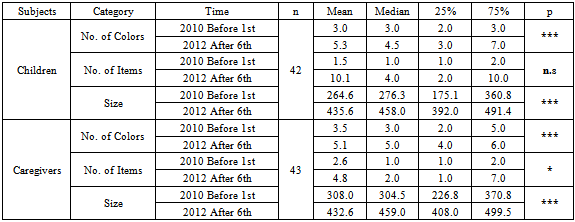

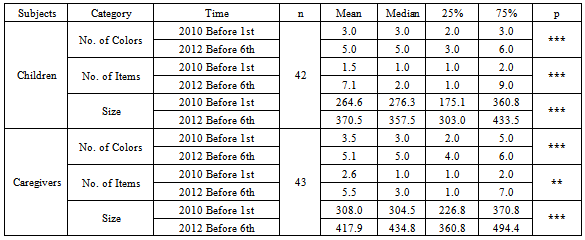

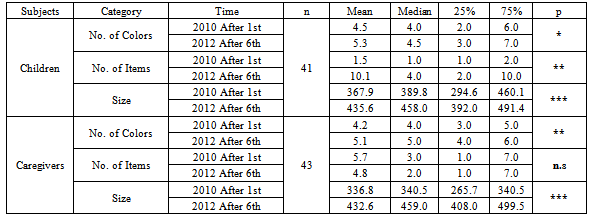

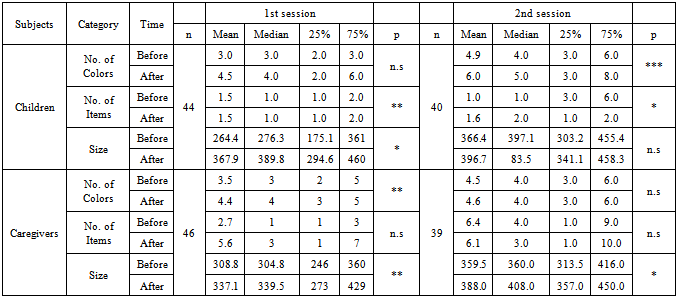

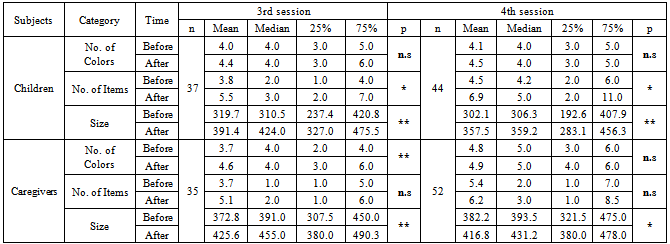

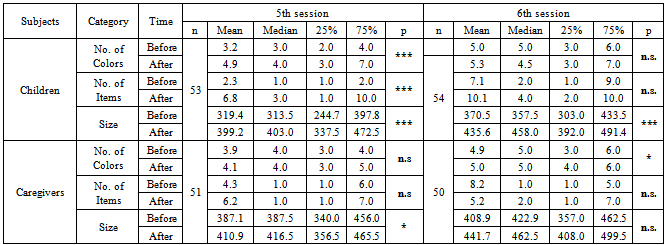

1) Means, medians, 25th and 75th percentile values, and p-values for the number of colors, items, and size of children and caregivers’ drawings before and after each of the six program sessions are shown in Tables 1–3.For all six sessions from 2010 to 2012, the number of colors, items, and size of the drawings increased after each session; significant differences were thus observed in one or more categories.Regarding the differences affecting a single category, a significant difference was observed only once among children for the category of size in the sixth session. Among the caregivers, significant differences were observed in the categories of size in the second session, size in the fourth session, size in the fifth session, and number of colors in the sixth session.Significant differences were observed in precisely two categories on four occasions among children and twice among caregivers. Among children, significant differences were observed in the two categories of items and size in the first session, colors, and items in the second session, items, and area in the third session, and colors and size in the fourth session. Among caregivers, significant differences were observed in the two categories of colors and size in both the first and third sessions. Finally, significant differences were observed in all three categories among children in the fifth session. Thus, while significant differences were found among children for all three categories, significant differences were only observed among adults in terms of colors and size; for adults, any changes in number of items were non-significant.In order to assess the chronological effects of the wood education program, we compared the number of colors, items, and size in the first and sixth sessions for children and caregivers, respectively. Comparisons were made for three different time points as shown in Table 4. The results of these comparisons are represented in Tables 5–7.Regarding the changes from before the first session to after the sixth session (Table 5), children showed increases and significant differences in terms of the number of colors and size, while caregivers showed increases and significant differences in all three categories.Table 1. Assessment of Children and Caregivers’ Drawings in 2010 (First and Second Sessions)

|

| |

|

Table 2. Assessment of Children and Caregivers’ Drawings in 2011 (Third and Fourth Sessions)

|

| |

|

Table 3. Assessment of Children and Caregivers’ Drawings in 2012 (Fifth and Sixth Sessions)

|

| |

|

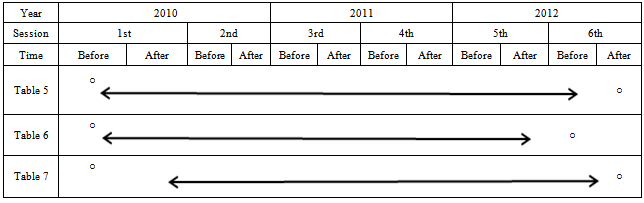

Table 4. Time Points Used in the Chronological Assessment of Drawings

|

| |

|

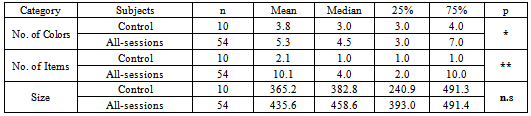

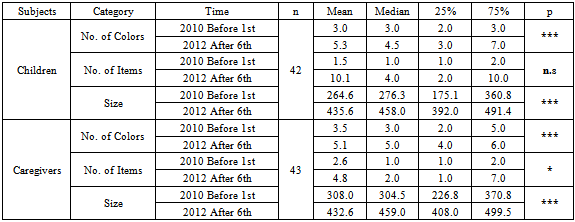

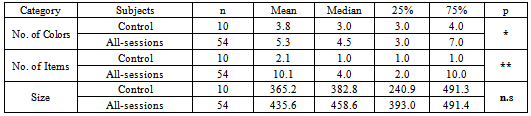

Regarding the changes from before the first session to before the sixth session (Table 6), both children and caregivers showed increases and significant differences in all three categories of number of colors, items, and size.Regarding the changes from after the first session to after the sixth session (Table 7), children showed significant differences in all three categories, while caregivers showed significant differences in terms of the number of colors and size.In order to verify the effects of wood education while accounting for child development, we calculated the means, medians, 25th and 75th percentile values, and p-values for number of colors, items, and size. These values were calculated for a 2010 pre-wood education control group and the all-sessions group (Table 8). Significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of the number of colors and items. No significant difference was observed for size.Table 5. Assessment of Children and Caregivers’ Drawings (Before the First Session and After the Sixth Session)

|

| |

|

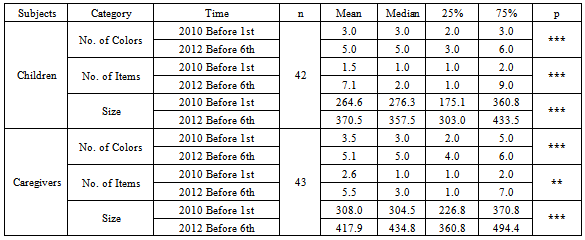

Table 6. Assessment of Children and Caregivers’ Drawings (Before the First Session and Before the Sixth Session)

|

| |

|

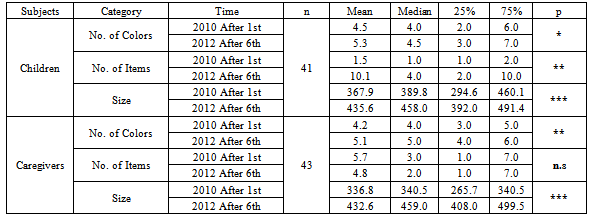

Table 7. Assessment of Children and Caregivers’ Drawings (After the First Session and After the Sixth Session)

|

| |

|

Table 8. Comparison of Drawings between the Control and All-sessions Groups

|

| |

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Chronological Effects of the Wood Education Program

The results from the wood education program indicated that the number of colors, items, and size of the drawings were greater after each session than before it. The chronological effects of wood education included marked increases among both children and their caregivers in the final session compared with the first session. Changes in the drawings were thus seen to indicate the beneficial effects of the wood education program.Self-expression is the transmission of one’s own inner feelings to others, and drawing is a stronger form of self-expression than other types of artistic activities. By expressing themselves, children reaffirm their own experiences and amplify their feelings with regard to them). When children and caregivers do drawings after participating in the wood education program together, they reconfirm the educative session that they have just experienced. The increases in the number of colors, items, and sizes of the drawings point to a variety of feelings experienced by the children and caregivers, which may include their enjoyment of the wood education session among themselves or with friends as well as the seriousness and tension felt when trying to use the woodworking tools.There are many reports on the existing research that emotional relation with parent and child helps children’s development to the future[6-9]. For children yet to develop sufficient verbal expression, drawing is a vital method for expressing their emotions and feelings. The increases in number of colors, items, and sizes of the drawings suggest the beneficial effects of the wood education program.

4.2. Chronological Effects of the Wood Education Program while Accounting for Child Development

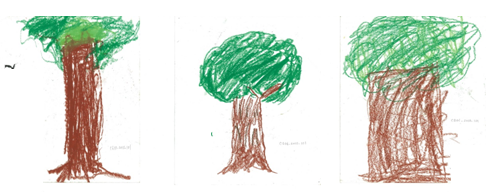

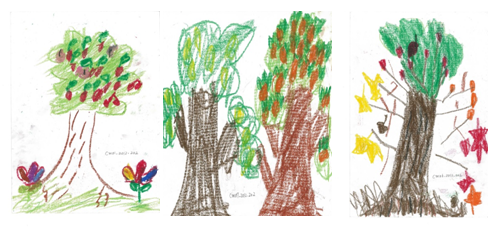

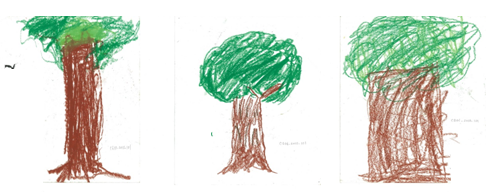

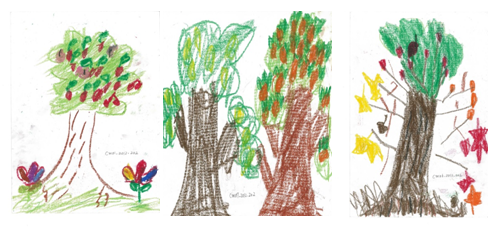

When comparing the three categories between the control group and the all-sessions group, a significant difference was observed in terms of the number of colors and items found in the drawings. These results suggest the effects of the wood education program over time, even when accounting for regular child development.Some of the drawings done by the control group and the all-sessions group are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively, which allows us to visually appreciate the effects of wood education. The drawings by the all-sessions group clearly use more colors and contain more items, such as nuts, fruit, flowers, and grass. These drawings appear to express the enjoyment and satisfaction that children gained from wood education as well as their inner richness and sense of accomplishment.A side-by-side comparison of the drawings made before the first session and after the final session demonstrates a transition in the children’s developmental stages). Whereas the children’s initial scribbles represent their infantile state, they later enter the schematic drawing stage and put more thought into drawing objects as they see them. | Figure 1. Control group drawings |

| Figure 2. All-sessions group drawings |

4.3. Possible Factors Influencing the Effects of the Wood Education Program over Time

4.3.1. Program Development in Respect of Child Development

In the first wood education program session in 2010, younger children worked with their caregivers to make boat building blocks. In the fourth session in year 2011, children and their caregivers made festival bells, and in the fifth session in 2012, they made wooden spoons. In the sixth and final session in 2012, children and their caregivers made two box chairs from Japanese cedar. As the children aged, the program thus became more advanced, and the children learned how to use new woodworking tools, such as hammers and saws, attempted more difficult tasks. The appearance of the children as they used saws to make the box chairs moved the people who were watching them at work. As the program developed from the simple stage of playing with a wooden block likened to a ship to making box chairs from Japanese cypress, it was considered that even five-year-old children had the ability to use large saws. It was suggested that the chronological effects of the wood education program promoted the children’s development.

4.3.2. Pursuing Wood Education in Nursery Schools

The continuous implementation of wood education in nursery schools was thought to be of great significance. In today’s society, numerous people have voiced their concerns about weakening community ties, and many young mothers in communities raise their children in isolation. The continued pursuit of wood education with the same class over a period of three years in a nursery school stimulated not only parent-child relationships, but also the relationships among the caregivers. This is suggested by the increases in number of colors, items, and sizes of the caregivers’ drawings after the wood education compared with the drawings done before it.In addition, many different types of people participated in the wood education in the nursery school, including various people from the community, wood education promoters, students and teachers from the Gifu Prefectural Academy of Forest Science and Culture, and nursery school teachers as well as the children and their caregivers. It was suggested that the children enjoyed using the wood and learned about its significance. A future pursuit of wood education is expected to take place in nursery schools, preschools, and institutions, which support infant care.

4.4. Development Characteristics: The Emergence of Drawings that Resemble Trees

In previous studies, when preschool children drew pictures of trees, they were aged approximately four years and six months when their drawings actually began to resemble trees; the children then showed increased and constant developmental changes as they grew older r[10]. According to the developmental stages of drawing, children transition from the scribbling stage to the schematic expression stage at around four to five years of age[5]. At this stage, children’s drawings progress from simple symbolic representations into figures that others can recognize.Ursula Ave-Lallemant stated that “When children express things, their expressions of trees always begin as scribbles.” She also indicates that it would be very rare for three-year-old children to recognize the shape of a tree without having practice in drawing trees[11]. A previous study also reported that three-year-old children’s drawings of trees almost never looked like trees[12]. In the present study, 33.9% of three-year-old children’s (aged under four years and seven months) drawings of trees after the second session actually resembled trees. It is possible that living in an area where there are many trees will also have had an effect. However, once the wood education began, children went walking in the nearby mountains where they learn the names of trees, smell them, learn about the shapes of leaves, and observe the stumps of cut trees; these and the other effects of wood education were indicated.

5. Conclusions

The beneficial effects of wood education were indicated in drawings done by children and their caregivers, namely, through increases in the number of colors and items used and the overall size of the drawings. The continuous application of wood education may be able to provide the expertise to support child development and childcare practices. Wood education programs may also be able to provide regular opportunities for parents and children to interact and help to support child development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (23330174, 24653134).

References

| [1] | Yamasita A. Recommendation of Mokuiku(wood education), Tokyo: Kaisei Sya,1-14,2008 |

| [2] | Kemuriyama Y., Nisikawa T. Book of Mokuiku (Wood Education, Sapporo: Asahi Shimbun Publishing,1-152,2011 |

| [3] | Japan Good Toy Committee. Mokuiku(Wood Education) Curriculum in Gifu model of development Execution Report document.2011;Tokyo: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries,1-20. |

| [4] | Anme T,Tomisaki E,Mochizuki Y. et.al. Practical use nature of a Mokuiku’s effect towards children's healthy developments and child-rearing supports. Journal of Health and Welfare Statistics,2012;59(1):21-25. |

| [5] | Itai, O., 2008,Children’s drawings and development: From real-world childcare education and handicapped child education.Kamogawa Syuppan,8–59. |

| [6] | Burchnal MR,Cambell FA, Bryant DM,Warsik BH, Ramey CT.Early Intervention and Mediating Process in Cognitive Performance of Children of Low-Income African American Families.Child Development,1997;68(5):935-954. |

| [7] | Gresham FM. & Elliot SN. Social skills rating system- Secondary. Circle Pines, MN:American Guidance Service, 1990; 1-223. |

| [8] | Caldarella P.& Merrell KW.Common dimensions of social skills of children and adolescents:A taxonomy of positive behaviors.School Psychology Review,1997:26:264-278. |

| [9] | Elkskin LK.& Elkskin N.Teaching social skills to students with learnig and behavior problems. Intervention in School & Clinic, 1998;33(3):131-141. |

| [10] | Fukada, N., 1957,A developmental study of Infant’s Tree Drawing, Japanese Psychological Research, 28 (5). |

| [11] | Kimura, K., 2010, A developmental study of Baumtest drew by infant, Soka University Bulletin, 309–332. |

| [12] | Ave-Lallemant, 1994, U. Baum-test (in German). Ernst Reinhards Verlag, Munich. Trans. Watanabe, N., Noguchi, K., Sakamoto, T., 2002, Baum-test: Interpretation and diagnosis of trees which reveal the self, Kawashima shoten. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML