-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2013; 3(5): 115-122

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130305.01

Perception of Social Support by Cancer Patients

Muzamil Ahmad1, Matloob Ahmed Khan2, Mahmoud Shirazi3

1Department of Psychology, Government Degree Collage, Ganderbal, J&K, India

2Department of Psychiatry, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

3Department of Psychology, University of Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran

Correspondence to: Matloob Ahmed Khan, Department of Psychiatry, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present study was aimed to assess the amount of social support perceived by cancer patients. For the purpose, 200 cancer patients (111 men and 89 women) who were going under treatment in the department of Radiotherapy and Oncology in Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Soura, Srinagar, Kashmir participated in the study. Social support was assessed by The Interpersonal Support Evaluation List – Short Form (ISEL-SF). Data was analysed using One Way ANOVA and t-test. The results indicated that the mean scores of older cancer patients were higher than middle age cancer patient, no significant difference was found between the mean scores of male and female cancer patients. Also, the mean scores of cancer patients with good income was higher than cancer patients with moderate income on social support scale.

Keywords: Cancer, Social-support, Age, Gender and Income

Cite this paper: Muzamil Ahmad, Matloob Ahmed Khan, Mahmoud Shirazi, Perception of Social Support by Cancer Patients, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 5, 2013, pp. 115-122. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130305.01.

Article Outline

1. Cancer: A Brief Introduction

- Cancer is often viewed as an acute and usually fatal disease. The word cancer comes from the Greek word for Crab, Karakinos .we are familiar with cancer as a tumor-an invasive and malignant growth. The ancient Greek physician who first described cancer noticed that some malignant tumor resemble a Crab-a hard mass with claw like extensions. In modern times, cancer has retained its reputation as an alien invader and is perhaps the most feared of all non-infectious diseases. Cancer is not the most common cause of death, but it is correctly seen as a progressive, often fatal, condition that cannot always be successfully treated.All tumors are not cancerous. Benign (non-cancerous) tumor tend to remain localized and usually do not pose a serious threat to health. In contrast, malignant (cancerous) tumor consists of renegade cells that do not respond to the body’s genetic controls on growth and division of cells. As people grow-up, normal cells divide rapidly until adulthood. After that, normal cells of most tissues divide only to replace dying cells or to repair injuries in a controlled manner. Cancer cells continue to grow and divide in an uncontrolled manner and can spread to other parts of the body. Cancer cells can accumulate to form tumors that may compress, invade, and destroy normal tissue. If cells break away from a tumor and get into the bloodstream or lymph system, they can be deposited in other areas of the body and form new tumors. The spread of a tumor to a new site is called metastasis. When the cancer spreads, it is still named after the part of the body where it started. Different cancer types vary in their rate of growth, pattern of spreading through the body, and response to different treatments[1].Cancer strikes people of all ages but especially middle-aged people and elderly. It occurs about equally among people of both sexes and can affect any part of the body. The parts most often affected are the skin, the digestive organs, the lungs and the female breasts. Without proper treatment, most kinds of cancer are fatal .In the past the methods of treatment gave patients little hope for recovery , but presently the methods of diagnosing and treating the disease have improved greatly.

1.1. Types of Cancer

- There are more than 100 identifiable forms of cancer. Although lung cancer is the most deadly form (accounting for about 30 percent of total cancer deaths annually), cancer can attack virtually any part of body with devasting results.The four most commonly occurring types of cancer are:CarcinomaThis is cancer of the epithelial tissues that forms the skin and the linings of the internal organs. Carcinomas accounts for approximately 85 percent of all adult cancers. They include cancer of breast, prostate, colon, lungs, pancreas, and skin.SarcomasThis is cancer of connective tissue, malignancies of cells in muscles, bones, cartilage and fluid. Much rare than carcinoma, sarcinomas account for only about percent of all cancers in adults.LymphomasThis is one of the types of cancers that form in the lymphatic system. Included in this group is Hodgkin’s disease. This is a rare form of lymphoma that spreads from a single lymph node and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, in which malignant cells are found at several sites. Approximately 60,000 new cases of lymphoma are diagnosed each year of which 90 percent are non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.LeukemiaThis type of cancer attacks the blood and blood-forming tissues, such as bone marrow. Leukemia leads to a proliferation of white blood cells in the blood stream and bone marrow, which impair the immune system. Although often considered a childhood disease, leukemia strikes for more adults (as estimated 25,000 cases per year) than children (about 3000 cases per year).Research has found that psychosocial interventions not only help the patients’ to reduce the stress but may also prolong survival in patients with cancer. Studies show that the higher the level of mood disturbance before the first cycles of chemotherapy, the poorer the clinical and pathological response to chemotherapy[2]. Psychosocial interventions may help in a number of ways such as enhancing treatment compliance, improving nutrition intake by patients, reducing high risk behaviors, altering coping strategies, improving the quality of life, providing group or other social support, and directly effecting a response to medical treatment. Psychosocial interventions have been found to alter host defenses, such as stimulating the immune system, although the mechanism of action in cancer patients is unclear.

2. Social Support

- Social support is a multi-dimensional concept[3,4,5,6,7] that has not been measured and defined in a homogenous way[8]. Social support is defined as the degree in which a person’s basic social needs are met through informal or formal social networks while enhancing health and well-being, regardless of their stress levels[9]. In the social support literature, the terms social support and social network are often used interchangeably[10]. The social network refers to a web-like structure comprising one’s relationships. This network includes family, neighbors, friends, employers, relatives, fellow employees, professional networks, and groups with which a family shares common goals, interests, lifestyles or social identity[11].A lot of research has been done on the benefits of social support on physical and psychophysical well-being. Social support seems to be associated with lower cardiovascular reactivity[12], and it improves the immune system[13,14,15]. Moreover, it was found beneficial for recovery, and readjustment to serious illness[16,17,18,19], and it even reduced mortality[20,21,22].Research has indicated that group interventions have been successful for many populations in reducing psychological distress[23]. Social support interventions are important because they provide individuals, especially those with chronic illnesses, with a way to communicate with others who have similar experiences. The basic purposes of social support groups for cancer patients is outlined, including free expression of feelings about living with the disease, fostering of support with others, educating participants about the disease itself, and helping participants learn better coping skills[24]. These purposes are relevant for most individuals with chronic disease.However, the research questions that this study intends to investigate are:Q.1. Is there significant difference between the mean scores of cancer patients’ social support and its sub-scales with consideration of age level?Q.2. Is there significant difference between the mean scores of cancer patients’ social support and its sub-scales with consideration of gender?Q.3. Is there significant difference between the mean scores of cancer patients’ social support and its sub-scales with consideration of type of cancer? Q.4. Is there significant difference between the mean scores of cancer patients’ social support and its sub-scales with consideration of income level?

3. Method

3.1. Sample

- The study was conducted on 200 cancer patients selected randomly, undergoing treatment in the department of Radiotherapy and Oncology in Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences Srinagar Kashmir. They were categorized into three groups: Group I, comprised of 98 general cancer patients including lung, stomach, prostrate, skin, and other types of cancer, Group II comprised of 57 Oesophagus cancer patients and Group III comprised of 45 breast cancer patients. The age of the respondents ranged from 25 to 85 with an average age of 49.66 years. Both genders (male and female) were included in this research.

3.2. Tool

3.2.1. Interpersonal Support Evaluation List – Short Form (ISEL-SF)

- This measure is a shortened version of the 40 item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List[25]. There are three areas in this scale which measures social support i.e. tangible support, appraisal support, and belonging support. The scale has fifteen items, five in each area. There are nine positive and six negative statements. The response alternatives are completely true, somewhat true, somewhat false, and completely false.Retest reliability for the full measure has been reported as .87, and the retest reliability for the subscales ranges between .71-.87[26]. Internal consistency reliability has been documented as ranging from .77-.86[26]. The three subscales of social support scale are reasonably independent of one another as indicated by their moderate inter correlations, which are in the .3 to .50 range. The maximum possible score on the scale is 60 and minimum is 15.

4. Results

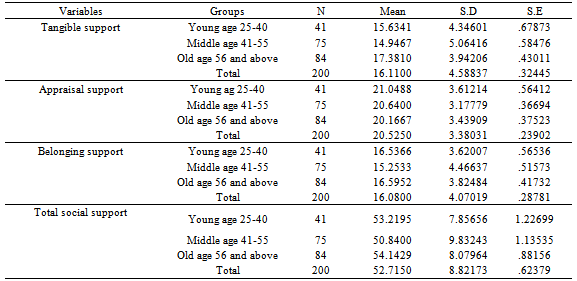

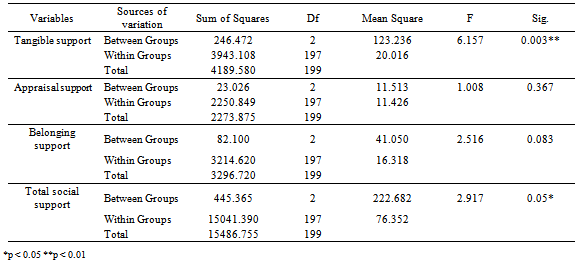

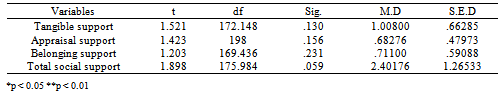

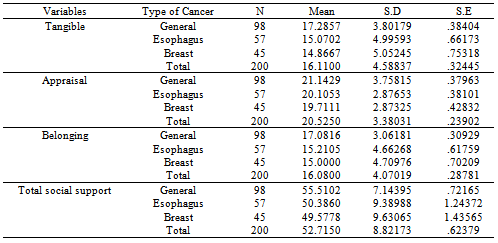

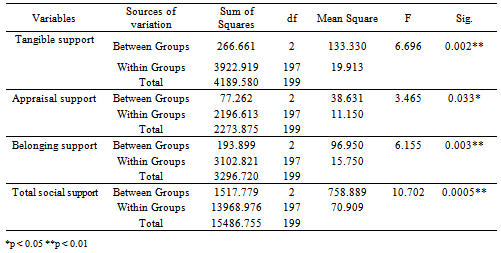

- The main purpose of this investigation was to study the social support among cancer patients. For the purpose, independent samples t-test and One Way ANOVA followed by Post-Hoc Analyses were used. All of the analysis has been done by SPSS.Q.1. Is there significant difference between the mean scores of cancer patients’ social support and its sub-scales with consideration of age level?In order to examine this question, the One Way ANOVA was used. The result is as follow:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

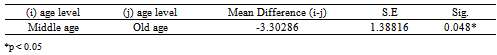

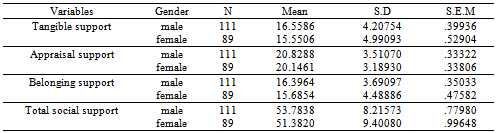

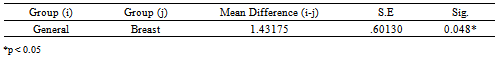

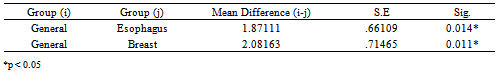

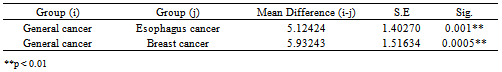

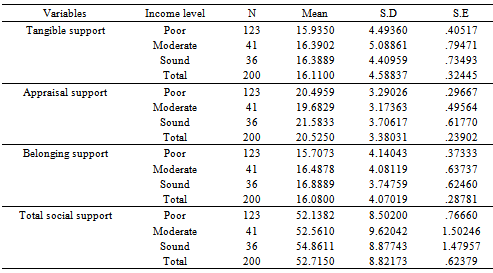

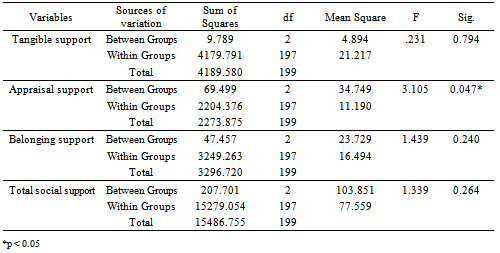

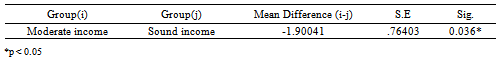

- As with any research, this study has limitations to consider. The most significant limitation of this study is that the data for all variables included in this study were collected via participants self-report. All though self-reports of participants are common ways of collecting data in the social sciences[27], the use of such data collection for the only assessment of stress is criticized for two major reasons: the inferences made by the researcher as to correlations and causal relationships between the variables under investigation might be artificially inflated by the problem of common method variance and secondly, studies involving self-report data are prone to response biases which need to be acknowledged and understood when interpreting results[28]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are not used in reporting of sample selection. Indian adaptation of the psychological test should have been used for administration on Indian population.Based on research question 1, the three age groups (young age, middle age and old age) were compared with regard to social support scale and its sub-scales. Because of (p=0.003<0.01), and (P=0.05≤0.05) there were significant differences between at least two groups on Tangible support and total social support. But there was no significant difference between the mean scores of three groups on Appraisal support and belonging support. The results showed that the mean scores of old cancer patients were higher than middle age cancer patient on tangible support and total social support.Tangible support is the result of concrete behaviors that help a person directly. The helping person intervenes personally in the problem situation and takes practical action such as help in household chores, giving a financial assistance, helping with work responsibilities or giving some other form of material aid. With increasing age a person becomes dependent on others, therefore besides help received from others concerning disease, a patients may receive help for various disabilities and weaknesses developed due to his old age. Therefore old aged cancer patients may perceive more support than younger patients. A study on disabled women, reported that greater reliance on family is associated with being of age ≥ 80, black, and living with others[29]. Also, younger patients and lower income women indicated they received less help than needed. In a study on aged people in Kashmir valley, result indicated that majority of the aged population were having family support as 85.7% (n=180) and only 14.3% (n=30) were not having any family support[30]. Therefore our result is in conformity with the mentioned findings.Based on research question 2, because of (p=0.130>0.05, p=0.156>0.05, p=0.231>0.05, and p=0.059>0.05) there is not any significant difference between the mean scores of two groups on social support and its sub-scales. That is, no significant difference was found between the mean scores of male and female cancer patients on social support and its sub-scales.The absence of difference between male and female cancer patients on social support may be due to the fact that, when a person is diagnosed with cancer the people around be they his or her family members, friends, physicians etc all may try to provide him or her care and support so as to comfort the patient, build his/her confidence and in a way ease patients’ stress irrespective of gender. The mean scores of cancer patients’ social support with consideration of gender have hardly any differences[31], therefore our result is in conformity with this study.Based on research question 3, the three groups/types of cancer (general, esophagus and breast cancer) were compared with regard to social support and its sub-scales. Because of (p=0.002<0.01, p=0.033<0.01, p=0.003<0.01, and p=0.0005<0.01), there were significant differences between at least two groups on social support and its sub-scales. The results showed that the mean scores of general cancer patients were higher than esophagus and breast cancer patients on tangible support, belonging and the total social support. And the mean scores of general cancer patients were higher than breast cancer patients on appraisal support.As the general cancer is not a particular type of cancer rather it consists of various kinds of cancers like skin cancer, stomach cancer, lung cancer, prostrate cancer, etc. some of these cancer types are not life threatening, agonizing with harsh symptoms. Some of cancer patients with less severity can manage activities in their daily lives at their own and therefore do not have much expectation from others. On the other hand esophagus and particularly breast cancer patients may feel themselves severely affected and therefore may raise many expectations on others who support them. With the daily hurdles, agony they may feel that the people around are not caring much about them as they expect and thus may report less amount of social support.Based on research question 4, because of (p=0.047<0.05) there is significant difference between the mean scores of at least two groups on appraisal support sub-scale. But there is not any significant difference between the mean scores of three groups on tangible support, belonging support and total scores of social support. The results showed thatthe mean scores of cancer patients with sound income are higher than cancer patients with moderate income on social support scale. One's socioeconomic status may be a major factor in whether or not an individual gets enough social support. The socioeconomic status is the measurement of level of income. As expected, anyone who comes from a lower socioeconomic class would be more likely to receive less social support. They basically may not have enough resources in their environment available to assist with social support. Cancer patients with low socioeconomicstatus have low social support scores[32]. Adults who have higher socioeconomic status tend to receive more social support[33].Thus our finding is in same direction.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML