-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2013; 3(4): 77-85

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130304.01

Distributive Justice, Age and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour among Non-teaching Staff of Benue State University

Aondoaver Ucho, Ernest Terseer Atime

Department of Psychology Benue State University P. M. B., Makurdi, 102119, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Aondoaver Ucho, Department of Psychology Benue State University P. M. B., Makurdi, 102119, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study investigated the impact of distributive justice and age on organizational citizenship behaviours. The study was conducted among non-teaching staff of Benue State University, Nigeria, and for this purpose, data was collected from 216 non-teaching employees from seven departments and units with a use of a questionnaire. Convenience sampling was used and SPSS 16.0 software was used to analyse the data. Findings revealed that there was no significant relationship between age and altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship and civic virtue. There was a significant relationship between distributive justice and altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship and civic virtue. The study provides implications and information for university managers and stakeholders to pay attention to distributive justice to increase organizational citizenship behaviours of non-teaching staff.

Keywords: Distributive Justice, Organizational Citizenship Behaviour

Cite this paper: Aondoaver Ucho, Ernest Terseer Atime, Distributive Justice, Age and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour among Non-teaching Staff of Benue State University, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 77-85. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130304.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

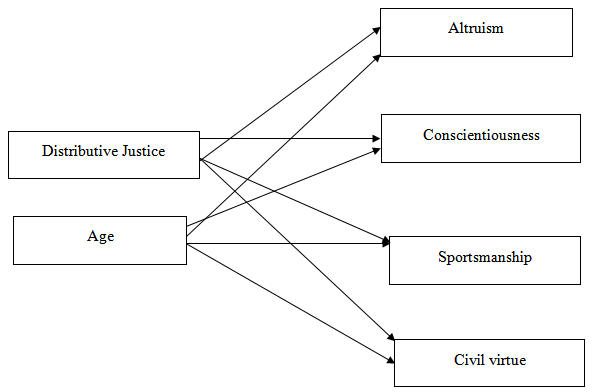

- Research has continued to report that for organizations to achieve their goals maximally, they must have workers who go beyond the call of duties in performing their jobs[1, 2, 3, 4]. The technical term for going beyond the call of duty is organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB)[5]. OCB can be defined as a behaviour that exceeds routine expectations or defending the organization when it is criticized or urging peers to invest in the organization[6]. OCB typically refers to behaviours that positively impact the organization or its members[7]. OCBs or extra - role behaviours are discretionary in nature and are usually not recognized by the organization’s formal reward system[8, 9, 10].Different forms of organizational citizenship behaviour have been reported by scholars[5]. The construct of OCB, from its conception, has been considered multidimensional. First, two dimensions were proposed: altruism and general compliance[40]. These two dimensions serve to improve organizational effectiveness in different ways. Altruism in the workplace consists essentially of helping behaviors. These behaviors can both be directed within or outside of the organization[3]. General compliance behavior serves to benefit the organization in several ways. Low rates of absenteeism and rule following help to keep the organization running efficiently. A compliant employee does not engage in behaviors such as taking excessive breaks or using work time for personal matters. When these types of behaviors are minimized the workforce is naturally more productive.Later, general compliance was deconstructed and additional dimensions of OCB were provided[5]. This deconstruction resulted in a five-factor model consisting of altruism, civic virtue,courtesy, conscientiousness, and sportsmanship[5, 8, 9, 11]. Altruism also refers to helping behaviour describes the voluntary willingness of employees to assist coworkers and helping new employees, for example, helping others with difficult tasks, and giving orientation to new employees. Civic virtue entails engaging in voluntary organizational activities and functions such as attending voluntary meetings, organising additional lectures by lecturers, responding quickly to letters. Courtesy has been defined as discretionary behaviors that aim at preventing work-related conflicts with others[44]. This dimension is a form of helping behavior, but one that works to prevent problems from arising. It also includes the word’s literal definition of being polite and considerate of others[3, 5].Conscientiousness here refers to discretionary behaviours that go beyond the basic requirements of the job in terms of obeying work rules, attendance and job performance[5, 13]. Similarly, conscientiousness means the thorough adherence to organizational rules and procedures, even when no one is watching. It is believed to be, the mindfulness that a person never forgets to be a part of a system[14], andsportsmanship on the other hand describes workers’ willingness to endure minor shortcomings of an organization such as delay in compensations.Organizational citizenship behaviour has been found to possess atleast two basic characteristics which include 1. It is not reinforceable directly (It is not required to be a part of the occupation of the individuals technically) and 2. they originate from the particular and extraordinary efforts and actions which the organizations expect from their employees in order to gain access to the success and effectiveness of the employees[12].Researchers have demonstrated that organizationalcitizenship behaviours make important contribution to individuals, groups and organizational effectiveness[3, 8, 15, 16, 17]. For instance, altruism or helping coworkers makes the work system more efficient because one worker can utilize his or her slack time to assist another on a more urgent task (18). Also, altruism involves helping specific individuals in relation to organizational tasks and this behaviour must be beneficial to the organization[13].There are many factors that can contribute to the determination of organizational citizenship behaviour. These factors ranged from personal attributes such as age and personality[19] to organizational issues such asorganizational justice[20, 21]. However, most of the researchers that have investigated organizational citizenship behaviour as organizational positive behaviour have considered it as a composite construct. However, literature has indicated that there are different dimensions of OCB. Therefore this research has gone a step further to consider distributive justice (a form of organizational justice) in relation to the four of the organizational citizenship behaviours of altruism, sportsmanship, conscientiousness and civic virtue. This study is also necessary because of the scarce research on the predictors of OCB in educational institutions[22] especially in Nigeria. Employees’ voluntary behaviour is quite important in education organizations as it is where the extra role behaviouris greatly needed for effective molding of the character of young adults.Generally, distributive justice concerns the nature of a socially just allocation of goods in a society. In organizational settings, distributive justice is seen as fairness associated with outcomes decisions and distribution of resources. The theoretical basis of organizational justice in general and distributive justice in particular is stemmed from the propositions of Equity theory by Adams, 1965[23]. According to this theory, workers always tend to compare their efforts and gains with the others' efforts and gains. The comparism then gives rise to the emotions, behaviours and satisfaction of the workers toward the organization. Workers will feel good and behave prosocially toward the organization if the comparisons indicate that the inputs or efforts and gains or compensations are equal or better than the others. On the other hand, if they feel that their co-workers’ compensation is better compared to their efforts; they will be dissatisfied and will show negative behaviours toward the organization. Distributive justice can therefore be enhanced when outcomes are seen to be justly distributed[24].Organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) are employee actions in support of the organization that are outside the scope of their job description. Such behaviours depend on the degree to which an organization is perceived to be distributively just[23, 25]. These researchers indicated variously that as organizational actions and decisions are perceived as more just, workers are more likely to engage in OCBs.In a study[26] investigated the impact of organizational justice on OCB and effects of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) as mediator between organizational justice and 5 dimensions of OCB among non-supervisory employees and supervisors in the banking organizations. They reported that organizational justice (distributive, procedural,informational, and interpersonal justice) is a significant determinant of OCB (Altruism, Conscientiousness, Courtesy,Sportsmanship and Civic virtue).In a meta-analysis, distributive justice was found to be a crucial predictor of OCB[27]. One of the first researchers to conduct research on organizational justice andorganizational citizenship behaviour is Robert Moorman. And in his study he found that there is a relationship between procedural justice and majority of the dimensions of OCB[28]. Similarly, when employees perceive fair treatment and trust in managers, they perform voluntarily beneficial acts for the organizations that are not their formal responsibilities[29].In his analysis, Chegini found that when employees of an organization feel a sense of organizational justice, it increases their functional ability and they show OCB. Furthermore, assessment of all the dimensions oforganizational justice showed they were positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviour[30]. This relationships show that it is necessary to make allocation and distribution of resources, policies and procedures fairly. In this way workers will be happier, satisfied and exhibit more positive behaviour in the organization.Empirical findings indicated that organizational justice led in employees’ trust in supervisors, which in turn encourages them to show more organizational citizenship behaviours [21]. In a study, the effects of fairness and trust in supervisor was investigated in relation to the OCB of academic staff of public universities. Trust in supervisor mediated in the relationship of organizational justice and OCB[2, 31]. Organizational justice (procedural, interactional and distributive justice) had significant positive correlation with trust in supervisor and trust in supervisor had strong positive effects on the different forms of organizational citizenship behaviour.Similarly, employees who perceive fair treatment from their supervisors are more inclined to show positive behaviours like OCB. In their explanations, Williams et al. emphasized that there are some preconditions and premises of organizational citizenship behaviours[32]. The primary condition is the perceptions of the workers about the decision and practices[31]. According to Aryee et al. theseperceptions set the trust of the workers into motion and then stiffen their citizenship behaviours. Positive state of the mind increases the possibility of performing certain organizational citizenship behaviours[32]. Workers feel happy and satisfied when they see that they are treated fairly by their organization, and this impact on their organizational citizenship behaviours[33, 34].Benue state university is an educational institution where knowledge is acquired and workers at the university generally are expected to put in extra-role behavior in order to mold the character and intellectual capacities of citizens. In trying to maintain the standards, workers pay and compensations are reasonably favourable compared to workers in many other government organizations. Therefore, it is expected that the university supporting staff (non-teaching staff) also reciprocate by going beyond the call of their duties thereby benefitting the university. Age as a personal variable has also been investigated in relation to helping behaviours in work organizations and other environment. For instance, age has been found to be significantly related to OCB.Older adults are known to conduct themselves on the basis of meeting mutual and moral obligations or internal standards whilst younger adults have a more transactional focus[35]. Furthermore, significant differences were found between young and old people in altruistic behaviour, a form of organizational citizenship behavioursuch that altruistic behavior was more among the older people[36]. Moreso, in a study, Cohen suggested that age in an organization is an important antecedent of OCB[37]. This is because age is considered as a main indicator of side bets, a term that used to refer to accumulation of investments valued by individual which would be lost if he or she were to leave the organization. More related studies also found similar results that age is a significant predictor of organizational citizenship behaviour among University staff[38].A study with American samples on the contrary indicated that age was not related to altruism[39, 40]. Similarly, a study using Nigerian sample reported age to be no predictor of organizational citizenship behaviour among non- academic staff of a university[19]. Considering this conflicting results it is clear that further studies are needed about the impact of age on the organizational citizenship behaviour of university staff. However, going by the fact that older adults are known to conduct themselves on the basis of mutual and moral obligations and internal standards[35] it is strongly convincing that older non-teaching staff of a university too would act on this basis and behave more positively toward their organization than the younger staff.From the above review therefore, the following model and hypotheses are developed:

- The model has two independent variables (distributive justice and age) and four dependent variables (altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship and civic virtue). The arrows indicated the summary of the literature and the hypothetical representation of the relationship of the study variables as postulated below: 1. Distributive justice will significantly predict altruism.2. Distributive justice will significantly predict conscientiousness.3. Distributive justice will significantly predict sportsmanship.4. Distributive justice will significantly predict civic virtue.5. There will be a significant relationship between age and altruism.6. There will be a significant relationship between age and conscientiousness.7. There will be a significant relationship between age and sportsmanship.8. There will be a significant relationship between age and civic virtue.

2. Method

- For the purpose of achieving the research objectives, the study employed a convenience sampling method. Many organization studies have used convenience approach in sampling respondents making it common and more prominent than probability sampling[41]. This may be because of the feasible nature of the approach compared to probability sampling method. The researchers distributed 250 copies of the questionnaire among the non-teaching staff of Benue State University Makurdi in Nigeria. They were distributed among the staff from the Library, Registry, Academic office, Bursary, ICT, Security posts and academic planning unit of the university. Two hundred and sixteen (216) copies of the questionnaire from the 221 returned were found usable. The remaining five (5) were discarded due to incomplete responses. Even though the researcher employed convenience sampling approach, participants were sampled from over 90 percent of the departments and units in university.The analyses indicated that 137 (63.4%) of the participants were males while 79(36.6) were females. Their ages ranged from 21 to 54 years with mean age of 35.24 years. From the number sampled, majority (126) of the participants were Tiv, the largest ethnic group in Benue State.65(30.1%) of the respondents reported they were single, 138(63.9%) were married while 10 (4.6%) were separated. 94 (43.5%) of them had Higher National Diploma/ bachelor degrees, 11 (5.1%) had masters degree and the remaining 111 had educational qualifications less than bachelor degrees. The participants’ years of service (tenure) in the university ranged from 1 to 21 years with the majority having 2 years of work experience in the university.

2.1. Instruments

- The questionnaire consisted of three parts: section one measured the demographic characteristics of the respondents, section two measured distributive justice, and section three assessed altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship and civic virtue.Distributive justice was measured using 5 item subscale developed by Niehoff& Moorman[42]. Sample items of this scale include: My work schedule is fair; overall, the reward I received here is quite fair. Respondents were asked to indicate there level of agreement for each statement by using 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree. The reliability of distributive justice scale developed by Niehoff& Moorman has been reported by other researchers using various work groups as high. For example, in a study of validity and reliability of organizational justice scale, distributive justice was reported to have .748 and .696 as reliability and validity coefficients respectively[43].The coefficients indicated that the scale is dependable and consistent. In this study also factor analysis was carried out to test construct validity of the scale. Then, with varimax rotation and factor loading the minimum of 0.5 as suggested by Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, and Tatham[45] was met. Then, the items were tested for their reliabilityCronbach’s Alpha was as high as .81.The four dimensions of the organizational citizenship behaviour were measured using 20 item scale developed by Organ &Konovsky[39]. Respondents indicated the extent of their agreement with each item on a scale from 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree. Here too factor analysis was carried out to test construct validity of the scale. Then, the minimum of 0.5 as suggested by Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, and Tatham[45] was met. The reliability (Cronbach Alpha) coefficients for the various scales were as follows: Altruism =.67, conscientiousness =.78,sportsmanship = .70 and civic virtue = .54.The demographic information such as age, gender, and years of working within the organization were measured by asking the participants to indicate their age, gender, years in the organization etc.

2.2. Data Collection

- The researchers personally administered thequestionnaires to the respondents at their various work stations and offices on the first and second campuses of the university.

2.3. Data Analysis

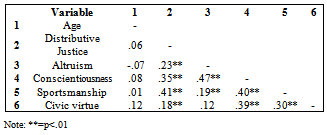

- Several techniques were used to analyze the data. The descriptive statistics such as frequencies, mean and standard deviation were employed to summarise the characteristics of the respondents. To assess the strength of relationships between the study variables, Pearson’s correlationcoefficient was employed.Liner regression was used to measure the influence of the independent variables of age and distributive justice in predicting the organizational citizenship behaviours of employees in the forms of altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship and civic virtue.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

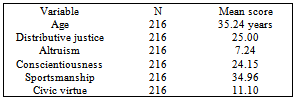

- Table 1 indicates thenumber and mean of participants on the study variables. The mean age of the participants was 35.24 years. Also, the average scores for distributive justice, altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship and civic virtue were 25.00, 7.24, 24.15, 34.96 and 11.10 respectively.

|

3.2. Correlation Analysis

|

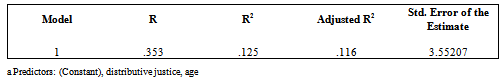

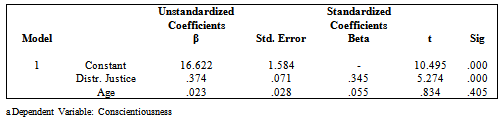

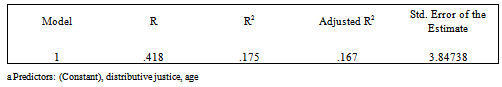

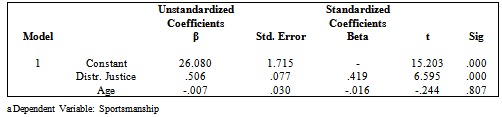

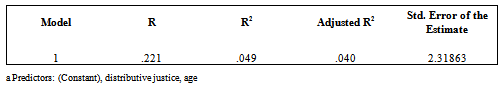

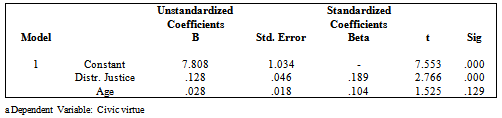

3.2. Multiple Regression Analysis

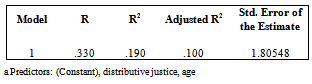

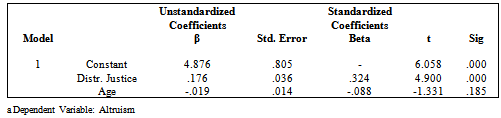

- The results of multiple regression analysis (see Table 3) show that independent variables (distributive justice and age) explained .109 of the variance in the dependent variable (altruism). The model summary table contains the coefficient of determination (R2), which measures the independent variables’ ability in explaining the variance in the dependent variable.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion, Limitations and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

- This study revealed that age is not a significant predictor of altruism. This finding is similar to other previous findings. For instance, various studies reported that age is not a significant factor in the explanation of altruistic behaviour [19, 39, 40]. Others however, reported the contrary that age is a significant predictor of altruism[35, 36]. All the studies that showed a significant relationship between age and helping behaviours used samples other than university employees. However the findings by Ucho which is consistent with the current study used university staff therefore it is believed that age is not a significant predictor of altruism among non-academic staff of universities. From the above explanation, it is clear that researchers interested in understanding altruistic behaviour among non-academic staff of educational institutions should investigate other variables, hence distributive justice.The findings of this study indicate that distributive justice positively predicted altruism. A possible explanation for this finding is that as non-academic staff of universities perceive fairness in the distribution of resources in line with their inputs, the more altruistic attitude and behaviours are practiced and adopted by them in the organization. Theoretically, when workers see that they are treated fairly and justly in the allocation of resources within an organization, they feel happier and are likely to exhibit more helping behaviours that can benefit the organization[2, 21, 24, 26, 30]. The results of this study indicate further that age is not a significant factor in the prediction of conscientious behaviour among non-academic staff of universities. This result seems to contradict the others which concluded that age in an organization is an important antecedent of OCB[35, 37]. It is important to report here that conscientious behaviour is studied here as a component of OCB. However, Kuehn and Al-Busaid and Cohen considered OCB as a composite variable including all the other dimensions. This may be the reason for the inconsistency in the findings.The analyses also show that distributive justice significantly predicts conscientious behaviour. The result agrees with other studies[26, 27].Similarly, distributive justice is found to be a significant predictor of sportsmanship. The report by Moorman is in line with this result. Moorman who was among the first researchers to conduct research on organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviour reported that there is a relationship between distributive justice and majority of the dimensions of OCB including sportsmanship[28]. This result also conforms to that of Deluga who found that when employees perceive fair treatment and trust in managers, they perform voluntarily beneficial acts for the organizations that are not their formal responsibilities[29].Age on the other hand is found to be no predictor of sportsmanship. The finding correspond that of Ucho[19]. However the result contradicts other researchers especially those who used samples other than university staff[38]. Last but not the least, the findings of this study shows that distributive justice significantly predicts civic virtue. Potential explanation for this finding is that, it is more likely for individuals to show constructive engagement in organizational activities (e.g., attendance at voluntarymeetings, responding promptly to correspondence, representing the organization positively etc.) when they perceive high level of fairness in the allocation of organizational resources.

4.2. Limitations of the Study

- The current study has a number of limitations that are worthy of note for future research direction. First and foremost, this research used cross sectional approach. Therefore, it will be good if subsequent research in this area employs the longitudinal method in order to have a deeper understanding or insight into age, distributive justice and organizational citizenship behaviour. The study used convenience sampling method in data collection. Future studies should consider more scientific approach in order to increase the external validity of the studies. Also, the research made use of employees from one university in Nigeria; therefore further research should include participants from other universities for effectivegeneralization of findings. Finally, the study showed that age accounts for a little percentage of the variance in all the components of organizational citizenship behaviour. Based on this it is therefore suggested that further research should include other demographic and organizational variables in the model in order to explain the variance in the dimensions or OCB.

4.3. Conclusions

- In this study age was investigated in relation to the various components of OCB. However, the result shows that age is not a significant predictor of all the dimensions of OCB. Therefore, university managers should not only depend on personal characteristics in terms of age to enhance the university employees’ level of OCB.Distributive justice positively predicted all the dimensions of OCB investigated. These relationships show that the way non-academic staff of universities feel about how resources are distributed in a university has significant implications on how they exert positive behaviours that can benefit their university. Therefore, university managers should give more attention for the employees’ level of OCB by employing maximum fairness in the distribution of university resources.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML