-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2013; 3(2): 57-62

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130302.03

Correlates of Individualism and Collectivism: Predicting Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Marcia A. Finkelstein

Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, Tampa, 33620, United States

Correspondence to: Marcia A. Finkelstein, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, Tampa, 33620, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The current study examined the relationship between individualism/collectivism and factors previously shown to influence Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB): in- vs. extra-role perceptions of citizenship behaviors and employee engagement with the job and the organization. We examined OCBI, behavior directed at individuals, and OCBO, which targets the organization per se. OCBO appealed predominantly to collectivists who were engaged with the organization and viewed service as part of the job. While OCBI, too, was largely the province of collectivists who viewed the activity as in-role, neither organization nor job engagement predicted OCBI. The data provide support for a conceptual model of OCB in which dispositional variables and employee-organization interactions influence amounts and types of citizenship activity.

Keywords: OCB, Individualism/Collectivism, Subjective Role, Engagement

Cite this paper: Marcia A. Finkelstein, Correlates of Individualism and Collectivism: Predicting Organizational Citizenship Behavior, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 57-62. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130302.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The present study examined the relationship between individual differences in individualism/collectivism and factors previously shown to influence Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB): employee engagement and in-role vs. extra-role perceptions of citizenship activity. OCB[30] refers to workplace activities that exceed the formal job requirements and contribute to the effective functioning of the organization. OCB also is referred to as “contextual performance” or “prosocial organizational behavior”[5,6,8] to emphasize its voluntary nature and distinguish it from “task performance” or assigned duties. Such activity enhances overall performance by increasing efficiency and reducing friction among employees[12,38]. Katz[24] argued that helpful and cooperative behaviors beyond what is explicitly required are essential to organizational effectiveness. Note, however, Bolino, Turnley, Gilstrap & Suazo[4] found that perceived pressure to perform OCB can lead to negative experiences, including job stress, and intentions to quit.Discretionary activities historically were viewed as reactive, a response to aspects of the work environment[44]. With the introduction of the functional perspective, Finkelstein, Penner, and colleagues[14,16,20,34] proposed a proactive conceptualization in which dispositional variables and employee-organization interactions together determine OCB. The present study examined the influence of several ofthese variables on citizenship behavior. Constructs examined include individualism/collectivism, in-role/extra-role perceptions of OCB, and job and organization engagement.Identifying individuals who are likely to perform OCBs is particularly important today, with organizations downsizing and employees asked to take on extra duties. Unemployment in the United States stands at 7.7%[9], making OCB essential to the operation of many institutions. The employees themselves also may benefit from the performance of OCB, as citizenship activities can improve work environment[12].Collectivism is one dispositional characteristic that has been associated with OCB. Some studies have shown that those with collectivistic values or norms were more likely to perform OCB and engage in cooperative behaviors[28,43]. Dyne et al.[13] reported that collectivism was related to OCB measured six months later, and Allen[1,7] found that collectivism was related to a specific form of organizational citizenship, serving as a mentor. The present study further investigated the influence on OCB ofindividualism/collectivism, examining the relationship between this construct and other variables known to influence OCB. In this investigation, as in prior work, we used a measure of OCB that specified two dimensions, differentiated according to the intended target. OCBI is prosocial behavior directed at individuals and/or groups within the organization; OCBO is behavior that focuses on the organization per se. Examples include assisting others with work-related problems (OCBI) and offering ideas to improve the functioning of the organization (OCBO).

1.1. Individualism/Collectivism

- Hofstede[22] proposed individualism and collectivism as a way of characterizing cultures. Collectivist societies consist of strong, cohesive in-groups whose members define themselves in terms of their group membership. Because one’s self-concept derives from identification with the group, the well-being of the whole takes precedence over individual desires and pursuits. In contrast, individualist cultures draw sharper boundaries between the self and others, emphasizing personal autonomy and responsibility over group identification. More recently, the constructs have been adapted to the individual and conceptualized as personality traits, albeit traits that are adaptable to situational demands[39,40]. Fundamental to the individualist is a focus on independence and self-fulfilment[31], placing personal goals over group goals[43] and personal attitudes over group norms[37,40] Collectivists, in contrast, are more likely to submerge personal goals for the good of the whole and maintain relationships with the group even when the personal cost exceeds the rewards.Some studies reported that employees with collectivist values were more likely to perform OCB[28,43]. Finkelstein and colleagues[11,19] examined the relationship between individualism/collectivism and specific OCB motives. Collectivism was more closely associated than individualism with concern for co-workers, while individualism was related more strongly to regard for the organization. Collectivism also fostered an identity as an organizational citizen, while individualism correlated negatively with a citizen self-concept. Overall, individualists and collectivists differed, not in amount of citizenship, but in why they served and how they perceived the experience.

1.2. In-Role/Extra-Role

- Although Organ[30] conceived of OCB as extra-role activity, subsequent studies questioned its discretionary nature. Van Dyne, Cummings, & Parks[41] maintained that to be considered extra-role, behavior must exceed expectations. Consequently, whether OCB assumes in-role or extra-role status will depend on the perspectives of the provider, the recipient(s), and observers. Further, expectations, and thus perceptions, change over time as one’s responsibilities and tenure with the organization evolve. In evaluating employees, supervisors often consider OCB, viewing citizenship as the duty of a productive employee rather than extra-role service[2,33] and allocation of rewards[1,33,42]. Additionally, supervisor perceptions of the motives underlying OCB affect performance ratings. Employees who appear to be motivated by a genuine desire to help are viewed more favorably than those whose citizenship behavior is dismissed as an attempt at impression management[21]. However, supervisor-focused impression management tactics can indeed influence a supervisor favorably[3].Beliefs about whether an activity is obligatory or discretionary differ among employees and between employees and their supervisors. Workers are more likely to engage in OCBs they consider in-role. According to Vey & Campbell[44] young workers in particular view many items typically contained in OCB instruments as in-role behaviors.

1.3. Employee Engagement

- Job engagement refers to the extent to which a worker is attentive to, and absorbed by, his or her job[36]. Engagement has been shown to be a distinct construct from attitude toward one’s job[10]. Engaging in the work fosters connectedness both to the work itself and to co-workers, and engagement becomes a form of self-expression[23]. Thus the concept of engagement is akin to role identity[20], the idea that carrying out a role shapes the self-concept and drives future behavior as the individual strives to behave consistently with this identity. Saks[35] noted that employees also may be engaged in the organization. He proposed a separate construct, organization engagement, measuring attachment to the organization per se. Saks found that both job and organization engagement predicted OCBO, with organization engagement the stronger predictor. Organization, but not job, engagement predicted OCBI.

1.4. Hypotheses

- We hypothesized that citizenship behaviors derive in part from individual differences in individualism/collectivism. Collectivists judge themselves by their contributions to the group, and that connection is part of an individual’s self-definition. Therefore, collectivists, more than individualists, should be inclined to perform OCBs.

1.4.1. Hypothesis

- 1. Collectivism will correlate more strongly than individualism with performance of OCBO and OCBI.Defining oneself in terms of group membership should mean that collectivists consider OCB part of their responsibilities. Indeed, Finkelstein[17] reported that collectivism correlated with a sense of personal responsibility to those in need. Conversely, individualists value personal autonomy and goals, so helping others will be viewed as extra-role activity.

1.4.2. Hypothesis

- 2. Collectivism will correlate more strongly than individualism with perceptions of OCB as in-role behavior. For collectivists, the health of the workplace community is paramount. Therefore they are likely to invest themselves in the organization. Individualists, in contrast, focus more on their own jobs than on the organization as a whole. No differences between individualism and collectivism with regard to engagement with the job are proposed.

1.4.3. Hypothesis

- 3. Collectivism will be more closely correlated than individualism with organization engagement.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- Participants were a convenience sample of 190 undergraduates (131 female, 59 male) at a metropolitan university in the southeastern United States; the mean age was 22.57 years. They worked for a variety of organizations, all as permanent hires and all employed at least 20 hours per week, with an average of 27.45 hours. Every participant had been at the current place of employment for at least 6 months, and the average tenure was 2.44 years.Respondents completed questionnaires anonymously in exchange for extra course credit. No specific recruitment strategies were employed. They accessed the questionnaires online through the psychology department’s participant pool management software. An introductory paragraph explained that the purpose of the study was to learn about participants’ employment experiences. The instructions assured them there were no right or wrong responses, and they could withdraw at any time without penalty.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

- We measured self-reported OCB with Lee and Allen’s scale[25]. The instrument assesses OCBO and OCBI by listing behaviors and asking participants how often they engaged in each. The scale comprises 16 items, eight corresponding to OCBO (e.g., “Offer ideas to improve the functioning of the organization”) and eight to OCBI (e.g., “Help others who have been absent”). A Likert format ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always) was employed. The coefficient alphas for each factor in the current sample were .84 (OCBO) and .77 (OCBI). Many studies of OCB supplement self-report data with information from co-workers or supervisors. However, we were concerned less with obtaining an objective accounting of OCB than with people’s perceptions of their behavior and the factors that drive it. Effectively encouraging OCB requires understanding an individual’s views of his or her behavior and its influences.

2.2.2. In-role/extra-role

- Lee & Allen’s scale[25] also was used to assess the extent to which participants viewed OCB as in-role activity. Respondents reviewed each item and indicated the degree to which they perceived each behavior as part of the job. Response alternatives ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alphas were .85 for OCBO items and .80 for OCBI items.

2.2.3. Individualism/collectivism

- We measured this construct with the scale by Singelis et al.[37]. The instrument contained 27 items, 13 assessing individualism (e.g., “My personal identity, independent of others, is very important to me.”) and 14, collectivism (e.g., “It is my duty to take care of my family, even when I have to sacrifice what I want.”) The 5-point rating scale had alternatives ranging from 1 to 5 (Strongly disagree to Strongly agree). Coefficient alpha was .75 for individualism and .76 for collectivism.

2.2.4. Employee Engagement

- The 11-item instrument by Saks[35] measured job (5 items) and organization (6 items) engagement. An example of the former is “Sometimes I am so into my job that I lose track of time.” The latter includes “Being a member of this organization makes me come ‘alive.’” Participants indicated the degree to which they agreed with each statement, utilizing a Likert format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).Coefficient alphas were .69 (job engagement) and .84 (organization engagement).

3. Results

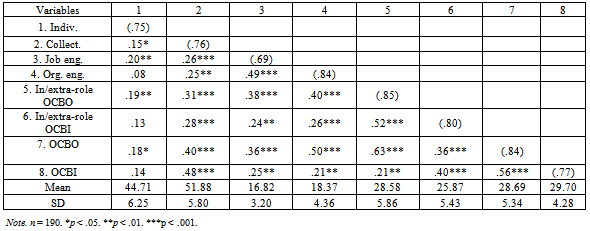

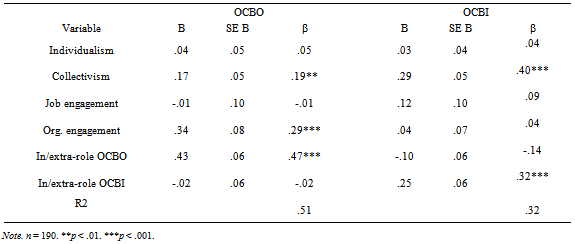

- The results are organized around the hypotheses that were tested. Table 1 presents the correlations among the variables along with their means and standard deviations. The first hypothesis concerned the association between individualism/collectivism and OCB and was supported by the results. The correlation between collectivism and OCBI (r = .48) was stronger than that between individualism and OCBI (r = .14), t(187) = 4.04, p < .01. Similarly, collectivism was associated more strongly than individualism with OCBO[r = .40 and r = .18, respectively; t(187) = 2.52, p < .01.]The findings did not support Hypothesis 2, which linked individualism/collectivism to perceptions of OCB as in-role or extra-role. Collectivism was no more associated than individualism with the perception of OCB as in-role behavior. This was true for both OCBO[r = .31 vs. r = .19, t(187) = 1.33, ns] and OCBI[r = .28 and r = .13, respectively, t(187) = 1.63, ns].As predicted (Hypothesis 3), collectivism correlated more strongly than individualism with organization engagement (r = .25 and r = .08, respectively; t(187) = 1.83, p < .05. In contrast, individualism and collectivism were nearly identical in the strength of their correlations with job engagement[r = .26 for collectivism and r = .20 for individualism; t(187) = .66, ns.]While the correlations suggested systematic differences in relationships among variables, the analyses also revealed large intercorrelations. To determine the unique contributions to OCB of individualism/collectivism, engagement, and in-role/extra-role perceptions, regression equations were calculated. All variables were simultaneously entered as predictors of OCBO and OCBI, respectively.

|

|

4. Discussion

- The results paint a partial portrait of employees most likely to engage in OCB. OCBO appealed predominantly to collectivists who were engaged in the organization and viewed citizenship as part of the job. OCBI, too, was largely the province of collectivists who viewed their citizenship activities as in-role. However, organization engagement did not predict OCBI. While absorption in one’s job boosts task performance[25], job engagement did not appear to foster either type of OCB. The salience of group membership helps explain the large contribution of collectivism to OCBO and OCBI. The two activities benefit the group, either the organization as a whole or other individuals. For collectivists, using one’s time and talents for the common good and maintaining harmonious relationships are both valued traits. Satisfaction derives from successfully carrying out social roles and obligations[31]. Recent examinations of OCB been influenced by studies of another prosocial activity, volunteerism. The two share important attributes. Both involve long-term, planned, and discretionary activities that benefit non-intimate others. The relationship between collectivism and helping, evident in OCB, also matches findings in the volunteer literature. Finkelstein[17] reported that collectivism, but not individualism was associated with time spent volunteering, while Finkelstein[18] found the same result for informal volunteering. The positive associations between collectivism and OCBO and OCBI, respectively also reflect the collectivist belief that citizenship activities are part of the job. In contrast, individualists feel less obligated to be of service because they primarily value personal success. Relationships and group membership matter insofar as they enable one to attain self-relevant goals[31]. Assisting others or the organization will be attractive only to the extent that helping provides the employee with benefits that otherwise would be difficult to acquire[43]. Individualists are pragmatic volunteers, using their skills to foster independence in others while simultaneously benefiting themselves[32].

4.1. Study Limitations/Conclusions

- That our OCB instrument categorized the activity according to the target of citizenship behavior potentially affected our conclusions. Some scales utilize additional categories such as altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy and civic virtue[30]. Still others examine interpersonal helping, individual initiative and industriousness, and the extent to which one defends and promotes the organization[28]. Different instruments could reveal somewhat different relationships among variables.The participants, though relatively long-term permanent employees, also were college students. At each stage in life (and employment history), new goals and priorities take precedence. These affect decisions about any motivated behavior, including OCB. For example, career advancement may be most important early in professional development, while the opportunity to give back may predominate later. Family obligations and other outside considerations also change throughout one’s work life, and these affect people’s motives for OCB as well as the types of activities in which they engage. Our relatively small sample size and the variety of organizations at which participants worked may have contributed to underestimating the influence of some variables. We did not ascertain the types of jobs respondents held or the types companies that employed them, thus limiting the generalizability of the present results. A complete understanding of the factors that underlie OCB will need to include workplace factors and interaction between individual and workplace. However, our limited sample makes the significant results obtained even more striking and the present findings are all the more noteworthy for supporting our conceptual framework. From a practical standpoint, the data suggest that employers should benefit from hiring collectivist-oriented workers. Training and mentoring programs could encourage socialization and reward cooperation and mutual help rather than competition[13]. Borman, Penner, Allen, & Motowidlo[7] maintained that behaviors such as OCB contribute to organizational effectiveness because they help create the psychological, social, and organizational context that helps employees to perform their jobs. Citizenship behavior lubricates the social machinery of the organization, increasing efficiency and reducing friction among employees[12,38]. Encouraging workers to serve in ways that best suit their talents and interests fosters organization engagement. Engagement, in turn, spurs OCB, perhaps because engaged employees tend to view OCB as in-role behavior[26,27,29].

5. Conclusions

- The findings provide new support for the idea of dispositional, as well as organizational, variables as contributing to OCB. The relationship between collectivism and citizenship behavior is consistent with that between collectivism and other prosocial activities, particularly volunteerism[15]. The results also provide additional support for the utility of a conceptual model that includes engagement and in-role/extra-role perceptions in the prediction of OCB.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML