-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2013; 3(2): 49-56

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130302.02

Rosenzweig Frustration Test to Assess Tolerance to Frustration and Direction of Aggressiveness in Criminals

Elizelma Ortêncio Ferreira, Cláudio Garcia Capitão

São Francisco University, Rua Alexandre Rodrigues Barbosa, 45 Itatiba – São Paulo, 13253-231, Brazil

Correspondence to: Cláudio Garcia Capitão, São Francisco University, Rua Alexandre Rodrigues Barbosa, 45 Itatiba – São Paulo, 13253-231, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present study aimed to evaluate the tolerance to frustration and aggressive feelings of prisoners by the help of Rosenzweig Frustration Test (RFT). Besides, it also verified the relationship between the type of offense and aggressiveness direction. The study was approved by the Ethical Research Board Committee of São Francisco University, followed by the volunteers signing an informed consent form, which faithfully observed all resolutions of the National Ministry of Health. The study included 125 prisoners of a heavily guarded prison in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. The age of participants ranged from 19 to 46 years (M = 29.8 years, SD = 6.4 years). The application of instruments was collective, into subgroups of approximately 20 subjects. A questionnaire was applied to characterize the sample and RFT, with an approximate duration of 1 hour. On investigating the extent to which the RFT factors differed from the groups, we observed significant differences between the groups that committed theft and the group that committed other offenses (theft x factors, Λ = 0.95, p = 0.05). Hence, it was concluded that there was a presence of low frustration tolerance in the sample of prisoners, especially for the group that committed theft, compared to the group that committed other types of offenses.

Keywords: Rosenzweig Frustration Test, Psychological Assessment, Criminals, Aggressiveness Direction

Cite this paper: Elizelma Ortêncio Ferreira, Cláudio Garcia Capitão, Rosenzweig Frustration Test to Assess Tolerance to Frustration and Direction of Aggressiveness in Criminals, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 49-56. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130302.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Several theories have evolved with time, which address the capacity for tolerating frustration. The present study focuses on the one that claims to be a natural ability to tolerate frustration, the mother having an important role to the baby’s distress, along with providing the child’s basic needs[11,2,26].The thought formation has the frustration of some basic needs, which are imposed on the newborn as its starting point, a process in which the essential is the greater or lesser child capacity for tolerating hatred resulting from the frustration of their basic needs. In case the capacity to tolerate frustration is sufficient, the experience thus becomes an element of thought, and develops ways to think about it. Whereas, if the ability to tolerate frustration is insufficient, the experience is internalized as something evil that must be evaded and expelled. The dropout and expulsion, of that something evil, is done by the means of motor restlessness of the child, and through the act without thinking as an adult[2].Frequent and intense exposures to experiences of frustration such as anxiety, trigger reactions. Anxiety is a reaction that involves defensive action, often accompanied by feelings of hostility and aggressiveness, according to the intensity and amount of tension in the baby’s mind[11,26,14].According to Rosenzweig[16-20], aggression is one of the alternative responses for situations of frustration. For the author, there are two types of frustration: (i) primary, and (ii) secondary. The primary frustration or deprivation is characterized by the amount of stress and subjective dissatisfaction, resulting from the absence of an essential final situation to the satisfaction of any active needs. On the other hand, secondary frustration consists of obstacles or difficulties occurring in the way, which leads to the satisfaction of any needs. The author, in particular, refers to the second type when defining frustration, since every time the body encounters an obstacle or difficulty, more or less insurmountable in the way that leads to the satisfaction of any vital necessity.Another important formulation in the general theory of Rosenzweig frustration[16-20] is defined by the attitude of the person who tolerates frustration without losing the psychological adaptation; in other words, without resorting to different types of inadequate responses. This formulation covers the phenomenon of adaptation as a whole, along with implying the existence of individual differences in situations of frustration tolerance. These differences are thus related to the amount of pressure of needs, and also with the person’s personality characteristics. However, the tendency to evaluate negatively, like to be suspicious of others or to suspect, may influence the degree of frustration tolerance.The determinants of frustration tolerance are somatic and psychological factors. The somatic factors include the constitutional and hereditary factors (nerve variations, etc.) and acquired somatic elements (fatigue, physical illness, etc.); whereas, psychological factors are determined by the avoidance and protection against the frustrating situations of early childhood, which later incapacitates the person to respond appropriately to any frustration. On the other hand, excessive frustration contributes to the creation of low tolerance areas, as it compels the child to use ego defenses, which may inhibit its further development[16-20].In frustrating situations, the body aims at restoring its integrated operation to maintain its balance. Thus, every response to frustration is adaptive; however, under psychological point of view, the responses are sometimes inadequate, being appropriate only when there is a predominance of responses with the progressive tendencies of personality, as compared to those that are regressive. While considering regressive responses, which connects the person to the past incorrectly interfering with subsequent reactions, the responses may be considered as less suitable, regarding the person is not freely allowed to face new situations[16-20].The criminals who fail to manifest any guilt feeling are apparently not internalized a set of moral values, which could dispose as a repertoire of self-control. This configuration is particularly true, when the superego functions remain almost exteriorized and do not imply any intra-psychic conflict. However, the criminals can show their conflicts in different ways, linked to antisocial behavior (theft, vice, etc.) instead of trying them as subjective states of conflict, followed by internal malaise[5,6].Based on the explanation of Winnicott[25] and Siegel[22], the tendency for antisocial behavior lies in the rediscovery of one’s own aggressiveness, which is the inherent aspect of the existence of one’s true inner self. Besides, antisocial behavior appears as a sign of hope, and is closely related to deprivation, which is a situation linked to specific failure. Now, stealing, along with the relation to a sense of deprivation that occurred long before the aggressive explosion, means that the person is actually seeking the ability to find objects, rather than just looking for an object.Based on the understanding for the dynamic operation of the delinquent act, Costa[4] and Winnicott[26] suggested that this may express the hope of rescuing any lost aspect of the primitive self, undiscovered or not integrated to the true inner self. In other words, a feeling of being loved just the way they are: a host condition that allows the person to feel unique. Generally, through the antisocial attitudes, people express their unconscious appeal as a pain expression. Such type of pain are usually caused by neglect, abandonment, deprivation, poverty, and threat of self-annihilation or sense of self-esteem, whose removal destroys the feeling of belonging or being a part of any social group.Adorno[1] draws attention to the fact that 11.7% of all police records in the city of São Paulo were related to injuries resulting from assaults. This proportion was, surprisingly, three times higher than the illegal weapons possession and drug trafficking cases. Besides, the author also highlighted images, conveyed by print and electronic media, showing dramatic scenes of daring and violent adolescents, devoid of all moral restraints, cold and insensitive, not hesitating to kill. Hence, the public was frequently surprised by the news of a murder committed by a teenager during the course of a robbery. Moreover, it emphasizes the growing number of people violating criminal laws, among which existed a high proportion of children and adolescents as well.In the context of forensic psychology, it is often the duty of the psychologist to evaluate the psychological condition of the people who violate the law. Concerning this specific context, projective techniques are widely used in Brazil. The term projective technique, in broad sense, expresses the way by which the individual makes contact with the inner and outer reality[8].Concerning the projective psychological instruments used to assess the tolerance to frustration, the Rosenzweig Frustration Test (RFT) is such an instrument, in which the subject is deliberately placed under an allegedly frustrating situation. The response is then analyzed and classified according to the direction of aggression, as extra-punitive, intra-punitive and non-punitive, and by the type of subject reaction, namely: obstacle dominance, ego defense, and continued need[13].Rosenzweig[18] compared delinquents and non-delinquents, in order to confirm the predominance of responses in both groups. The sample included 250 delinquents and 250 non-delinquents. He noted a predominance of responses in the intra-punitive category, which indicated the aggressiveness directed to itself for the group of "non-delinquents". On the other hand, in the extra-punitive category, aggression was directed towards the environment, or other predominated in the responses of the "criminal" group. Thus, he concluded that a response of aggression depends on the game of a set of factors, which relate to the cognitive interpretation of the frustrating situation, with its intensity, the strength of internal and external controls, and above all, the tolerance to frustration.In another survey, conducted by Rocha[15], 60 delinquents and 60 non-delinquents (males) were compared in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in acts of vandalism. Subsequently, the survey result showed that the non-delinquents manifested more aggressiveness than the delinquents. However, the delinquency would be unrelated to the degree of aggressiveness of the individual, but with the lack of control over impulses, even those which are aggressive. Thus, it can be said that aggression is not only a characteristic of delinquent behavior, but also a non-delinquent characteristic itself.In the doctoral thesis, Souza[23] examined the aggressive behavior in its hereditary potential condition, and overt action caused by the environment. In order to investigate the construct of aggressiveness, the tests of Human Figure Drawing (HFD), Psychodiagnostic Miokinetic (PMK), and RFT were used. Moreover, the author also wanted to build a scale of aggressiveness from the obtained results. The research included three groups of culturally diverse women. The first group consisted of 30 minor offenders, the second of 25 novices from two religious orders, and the third of 30 university students of psychology. The application was collective for the tests of RFT and HFD, while it was individual for PMK. From the results obtained, only the extra-punitive variables discriminated the groups. Besides, it was impossible to build a scale of signals to identify aggressiveness by using the results.Stangenhaus and Cabral[3] analyzed the characteristics of 62 prisoners, comparing them with those of the 50 people in a control group. The history-questionnaire method was used, which included closed (yes or no) and open questions. Personality characteristics related to poor control of aggressiveness, combined with a low frustration tolerance, were found in the prisoners. These characteristics were described by other authors[10] as borderline and antisocial personality.Guillaume and Proulx[7] compared the personality characteristics of 16 violent criminals described as borderline, with 18 violent criminals described as narcissistic. The analysis results showed that the group of borderline criminals had problems related to drugs and alcohol, as well as the use of more physical aggression during robbery, while the narcissistic criminals apparently had a greater control on aggressiveness.In this study,the degree of tolerance to frustration of prisoners was assessed by Analysis of Profiles of Repeated Measures, a technique named by Tabachinick and Fidell[24]. This technique is a type of processing data, which is specific for a multivariate analysis of variance. The aim of this analysis was to answer whether the average profile of a set of measures (intra-subject part of the design) was different for different groups. The effect of the variable, Factors, plays a fundamental role from the statistical point of view, since its inclusion in the model permitted the reduction of the variance of error. However, once it is significant, it would explain a portion of the variance, removing it from the amount of error and implementing the statistical power of the test.The analysis of repeated measurements preserves the groups’ independence, even when the same subject, simultaneously, belongs to several groups, i.e. the same responder may have committed various types of irregularities in order to maintain the groups’ independence. Furthermore, such analysis aims at compensating the problem of Type I error inflation, which arises while making a series of t-tests in comparing the means of groups in various dependent measures[9].Given the few studies that dealt with assessing the tolerance or intolerance to frustration, the present study aimed at verifying the type of reaction to frustration in prisoners, and assessing the relationship of dependency between the type of offense (theft, robbery, kidnapping, homicide, larceny, etc.) and the direction of aggression through RFT. It was hypothesized that the prisoners who committed crimes, such as burglary, theft, kidnapping, and larceny armed a greater number of extra-punitive responses in the RFT. Such a tool might be a useful additional feature of psychological assessment in the prison context.

2. Method

2.1. Sample

- A total of 125 male prisoners, who were students of elementary and high school, participated in the study. Their ages ranged from 19 to 46 years (M = 29.8, SD = 6.4). The highest concentration of age range was between 26 and 30 years, and only one (1) subject was aged more than 45 years. Regarding their marital status, 53 participants lived in stable union, 48 were unmarried, and 24 did not report their marital status.Regarding educational qualification, among the 125 participants, 114 did not finish elementary school (91.2%), and only one subject had completed high school (0.8%). Among the 53 (42.4%) subjects who lived in stable union, 50 (40%) had incomplete primary education; whereas, among the 48 (38.4%) unmarried participants, 42 (33.6%) had incomplete primary education.

2.2. Instruments used / Materials

- The RFT is a projective test that was created with the purpose to verify, under a frustrating situation, whether the individual reacts with a response of tolerance or intolerance.It is understood that the individual, consciously or unconsciously, identifies with the character who is frustrated in the situations presented in the test, and is projected by the response it produces[21]. The responses were measured from the reaction of the individuals facing a situation, which most people regarded as frustrating (e.g., bumping and breaking mother’s favorite vase or getting completely wet by a car that went through a puddle of water at the exact moment when you went down the sidewalk). The presented situations prevented, disappointed, blocked and deprived the individual of something[19], and in certain circumstances even accused, insulted or incriminated.In order to facilitate identification by the individual, the test was composed of uniform character designs that reminded of comic books as stimuli; however, the size of responses and scope of instrument were limited. The instrument comprised a series of 24 drawings, each representing two characters placed in a state of frustration of common type. The drawing situation consisted of characters, from left, to define in a few words the frustration of another individual or their own. Consequently, the person on the right has an empty frame above him, designed to receive his words. In order to facilitate the identification of who will respond with the character, the features and gestures of the characters were systematically neglected in the drawing. The test had different versions for adults, adolescents, and children[16,17,18,20].The individuals’ responses obtained in each of the test situations were classified into two categories, which comprised, respectively, the direction and type of aggression. The response direction indicated where the aggression was directed by the frustrated individual; besides, it was subdivided into three sub-categories of responses, viz. (i) extra-punitive (E), in which the aggression was directed outwards. In this case, something or someone was found guilty by the frustrated individual; (ii) intra-punitive (I), in which the aggression was directed towards the individual; and (iii) non-punitive response (M), wherein the aggression was avoided, and the frustrating situation was described as insignificant, without fault, or as susceptible of being improved, i.e., the individual was content to wait for everything to improve, or he conformed to the problem[13].The type of reaction manifested by the individual states the way in which it drives or maintains its aggression, which further determines the type of its action in response to external stimuli. Moreover, it is also noted that the type of reaction is divided into different categories, namely: (i) type of obstacle dominance (OD), in which the obstacle that causes frustration is mentioned and emphasized by the subject; (ii) type of ego defense (ED), in which the individual throws blame on others or accepts responsibility, or even states that the responsibility of the situation is no more fit; and (iii) type of continued need (NP), in which the trend of response is directed towards solving the problem inherent to the frustrating situation. The combination of the six categories (three directions with the three types of aggression) produces nine factors, which allow the evaluation of tolerance to frustration (Rosenzweig, 1944).The responses of OD were conventionally designated by E’, I’ and M’; those of ED by E, I and M; and those of NP by e, i and m. The quotation of most answers required only a single factor. Besides, in order to quote two factors in the response of the individual, two sentences or distinct propositions were needed.

2.3. Procedure

- After the approval of the study by the Ethics Committee in Research of São Francisco University, as well as the authorization by the prison’s director, a contact was set up with the prisoners. The initial contact with the subjects was conducted through collective explanation of the research objectives, and also highlighting that the information would be kept confidential. The participants, who agreed to participate in the study, were scheduled to implement the instruments. This opportunity was given to signing of the Consent Form. The application was collective, into subgroups of approximately 20 subjects. We used a questionnaire to characterize the sample, and then the RFT was applied for duration of approximately 1 hour.

3. Results

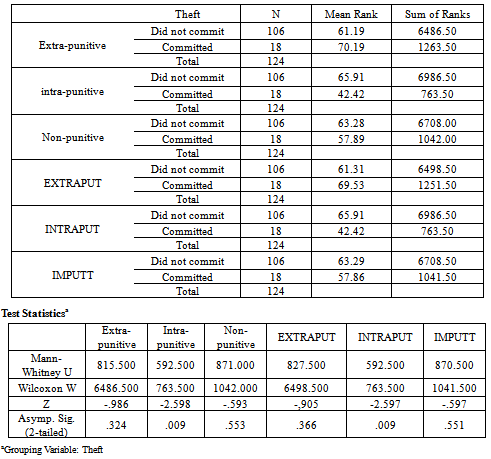

- Since the type of offense that the person practiced was not obtained, 124 participants were considered for the category of offenses. Besides, there was also an overlap of offenses for the same subject. Therefore, the criterion of considering the same subject in several categories of offenses was adopted for this particular purpose.Two hundred one offenses were obtained from the 124 subjects. Theft was the most committed crime, while kidnapping was a comparatively less evident crime.The RFT test, as previously mentioned, is a projective instrument that consists of 24 situations, under which the subject can make three responses. The responses are classified according to the direction of aggression and type of reaction. In this study, we obtained two responses per situation, i.e., (i) two sentences in the same situation of the test, and (ii) the statistics were performed using the SPSS software program. At first, the descriptive statistics of responses on the direction of aggression was presented, and then their frequency (see Table 1).

|

|

|

3.1. Analysis of Variance

- In order to investigate the differences among subjects who practiced different types of offenses in relation to the type of reaction and direction of aggression when frustrated, the Analysis of Profiles of Repeated Measures was performed, which consisted of a specificity of the Multivariate analysis of variance. This analysis, in particular, aims to answer whether the means profile in a set of measures (the intra-subjective part of design) is different for different groups[24].It was understood that the items in a given factor proposed a specific theme, which required from the subject a response that indicated its agreement with the statements. Thus, what was being measured, i.e., the dependent variable, was the agreement with the statements proposed; besides, the scores of participants in the three factors represented the profile of agreement in relation to the three themes proposed. Thus, this profile analysis investigated to what extent the profile of groups of individuals defined, depending on a given variable, was distinct.

|

4. Discussion

- Concerning the obtained results, some evidence was found to be responding to the inquiries of the proposed objectives. The descriptive analyses allowed the sample to be characterized, thus indicating that the highest number of crime committed, robbery, involved aggression against the other; however, these data were similar to those found by Adorno[1].Moreover, the analysis results also suggested how the subjects dealt with their aggressive feelings, and reactions to frustrating situations. When extra-punitive, intra-punitive and non-punitive factors were compared, it was found that most of the participants expressed their aggressive feelings than those repressing them, direct aggression to the other or equivalent objects through actions or motor actions, which led to the thinking about a low tolerance to frustration, and consequent lack of control over aggressive impulses [2,3,7,10,15,22].Similar results were also found by Rosenzweig[17-20], who observed a predominance of responses in the extra-punitive category of a "criminals" group. In frustrating situations, the subjects’ responses in the sample indicated that they tended to attack, as well as blame the other. This finding, thus suggested that the ego of such people, in frustrating situations, is the most important part of response, i.e., the ego makes them ignore their responsibility, seeking to assign blame to others. The low number of responses, and the type of OD, indicated that few subjects in this sample had the tendency to face frustrating situations as unimportant or unfavorably. Besides, these results suggested that the functions of the prisoners’ superego remained out, and did not imply intra-psychic conflict. Therefore, they showed their conflicts through antisocial behavior[5,14,26].Comparisons among the groups of robbery, theft, kidnapping, murder and others, in the three RFT factors, showed significant mean differences between the groups that committed theft offense and those that did not commit it. Moreover, it was found that the individuals who theft, in frustrating situations, tended to react driving the aggression to the other or equivalent objects, which was the representative or cause of frustration. The univariate analysis showed that the significant differences tended to be subdivided, depending on the intra-punitive factor. However, this finding suggested that the theft offense group reacted in a frustrating situation, thus driving the aggression to one's own self, as compared to those who did not commit. In other words, the theft group had greater instability among the factors relative to the direction of aggression; whereas, those who did not tend to theft had apparently greater stability. Regarding the instability of direction of aggression, the study findings were observed to be similar to those found by Guillaume and Proulx[7]. Besides, the study results were found to be different from those found in another study with groups of different populations, in which the factor that discriminated the groups was the extra-punitive factor[23]. In fact, the significant average difference for the intra-punitive factor suggested the lack of contact with guilt feelings[5].

5. Conclusions

- Among the various limitations of the study, it was pointed out that the technique used in this study, the RFT drawings, exhibited surpassed features that were built according to the reality of 30 years, which may have hindered the understanding of the participants during some test situations. Besides, it also emphasized the existence of problems, arising due to the fact that no studies were conducted on the standardization, with the RFT, for Brazilian population, especially for prisoners.Some authors, who investigated the tolerance to frustration, mentioned that these individuals suffered repeated and/or intense exposures to frustrations at a time prior to the antisocial acts. Subsequently, they expressed, through the theft and other antisocial attitudes, their pain caused by social rejection, specifically by parents, which ultimately led to a vicious cycle of criminal behavior. This study, however, does not have any data on the previous life of the sample, and thus did not even aim at investigating it; hence, it could not determine the etiology of antisocial acts. However, it is highly recommended that this variable should be studied in further research.It is of great interest to know that further research on assessment of the degree of tolerance to frustration in prisoners, as well as the studies on RFT standardization for Brazilian population, especially for prisoners, will be developed. Besides, other studies performed on prisoners’ profiles, using the RFT, including the data on life history, will help to improve the reliability of the results measured by the instrument. Furthermore, the studies on RFT will effectively contribute to increase the credibility of the psychology professional in particular, who assesses the psychological condition of the people who violated criminal laws in legal terms. However, it is also suggested to conduct a comparison of prisoners’ profiles with other populations, and assess the results by other instruments.

References

| [1] | Sérgio Adorno, “A delinqüência juvenil em São Paulo: Mitos imagens e fatos”, Pró-posições, vol.13, no.39, pp.45-70, 2002. |

| [2] | Wilfred R. Bion, O aprender com a experiência, Rio de Janeiro: Imago, 1991. |

| [3] | M. A. A. Cabral, G. Stangenhaus, “Algumas características de personalidade de presidiários com as de um grupo controle sem antecedentes criminais”, Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, vol.41, no.1, pp.8-31, 1992. |

| [4] | J. F. Costa, Violência e psicanálise, 2ª ed., Rio de Janeiro: Graal, 1986. |

| [5] | Paul A. Dewald, Psicoterapia: un enfoque dinámico, Barcelona: Toray, 1972. |

| [6] | G. O. Gabbard, Psiquiatria Psicodinâmica na Prática Clínica, Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2007. |

| [7] | B. Guillaume, J. Proulx, “Caracteristiques du passage a l'acte de criminels violents etats-limites et narcissiques”, Canadian Journal of Criminology, vol.25, no.44, pp.51, 2002. |

| [8] | A. E. V. Güntert, “Técnicas projetivas: o geral e o singular em avaliação psicológica”, In: F. F. Sisto, E. T. B. Sbardelini & R. Primi (Orgs.), Contextos e questões da avaliação psicológica, São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, pp.77-84, 2011. |

| [9] | J. F. Hair, R. E. Anderson, R. L. Thatam, W. C. Black, Multivariate Data Analysis with readings, New Jersey: Prentice-hall international, 1995. |

| [10] | W. Harth, K. Mayer, R Linse, “The borderline syndrome in psychosomatic dermatology”, Overview and case report, J Eur. Acad Dermatol. Venereol, vol.18, no.4, pp.503-507, 2004. |

| [11] | M. Klein, Amor ódio e reparação: As emoções básicas do homem do ponto de vista psicanalítico, 2ª ed., Rio de Janeiro: Imago, 1975. |

| [12] | D. L. Levisky, Construção da Identidade, o processo educacional e a violência – uma visão psicanalítica, Pró-posições, vol.13, no.39, pp.99-111, 2002. |

| [13] | F. C. Moura, L. Pasquali, “Construção de um teste objetivo de resistência à frustração”, Psico-USF, vol.11, no.2, pp.137-146, 2006. |

| [14] | A. M. P. Nogueira, “Angústia e violência: Sua incidência na subjetividade”, Revista Latinoamercana de psicopatologia Fundamental, vol.4, no.1, pp.76-85, 2001. |

| [15] | Z. O. Rocha, Frustração e Agressividade em adolescentes delinqüentes e não delinquents, Tese de Concurso para Livre-Docência em psicologia do Desenvolvimento, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 1976. |

| [16] | S. Rosenzweig, Teste de Frustração: Manual de psicologia aplicada, Rio de Janeiro: CEPA, 1948. |

| [17] | S. Rosenzweig, “The picture association method and its application in a study of reactions to frustration”, Journal of Personality, vol.14, pp.3-23, 1945. |

| [18] | S. Rosenzweig, “Validity of the Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration Study with felons and delinquents”, Journal of Consulting Psychology, vol.27, no.6, pp.535-536, 1963. |

| [19] | S. Rosenzweig, “Aggressive behavior and the Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration (P-F) Study”, Journal of Clinical Psychology, vol.32, no.4, pp.885-891, 1976. |

| [20] | S. Rosenzweig, “An investigation of the reliability of the Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration (P-F) Study children's form”, Journal of Personality Assessment, vol.42, pp.483-488, 1978. |

| [21] | S. Rosenzweig, D. J. Ludwig, S. Adelman, “Retest reliability of the Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration Study and similar semi-projective techniques”, Journal of Personality Assessment, vol.39, pp.3-12, 1975. |

| [22] | Allen M. Siegel, Heiz Kohut e a Psicologia do Self, São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2005. |

| [23] | I. Souza, O comportamento agressivo em grupos culturalmente diferenciados, Tese de Doutorado, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Psicologia Clínica, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1990. |

| [24] | B. G. Tabachinick, I. S. Fidell, Using multivariate statistics, New York: Harper Collins, 1996. |

| [25] | D. W. Winnicott, Tudo começa em casa, São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1989. |

| [26] | D. W. Winnicott, Privação e Delinqüência, 3ª ed., São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1999. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML