-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2013; 3(1): 18-22

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130301.03

Empathy and Spirituality: Is there a Gay Advantage?

Chew Sim Chee , Amelia Mohd Noor , Aslina Ahmad

Department of Psychology and Counseling, Faculty of Education and Human Development, Sultan Idris Education University, 35900, Tanjong Malim, Perak, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Chew Sim Chee , Department of Psychology and Counseling, Faculty of Education and Human Development, Sultan Idris Education University, 35900, Tanjong Malim, Perak, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

It is commonly believed that gay people tend to be more emotionally sensitive. Due to the oppression and victimization, homosexual individuals could have evolved to become more empathic and spiritual. This study thus aimed to study the positive aspects of functioning in gay people (in this study, homosexual males) specifically empathy and spirituality by providing a comparative perspective. A total of 58 homosexual males (mean age = 31.3 years, S.D. = 10.1 years) and 46 heterosexual males (mean age = 21.9 years, S.D. = 4.3 years) participated. All participants completed an online survey on empathic and spirituality dispositions (using measures of the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid, Interpersonal Reactivity Index, and a measure on spirituality). Homosexual males evidenced higher level of empathic concern compared to heterosexual males. However, there are no differences in other aspects of empathy (i.e., perspective taking, fantasy, personal distress) and spirituality between homosexual and heterosexual males. There is also differential relation between different aspects of empathy with spirituality in homosexual and heterosexual males.

Keywords: Empathy, Spirituality, Sexual Orientation, Homosexuality

Cite this paper: Chew Sim Chee , Amelia Mohd Noor , Aslina Ahmad , Empathy and Spirituality: Is there a Gay Advantage?, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2013, pp. 18-22. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20130301.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to the American Psychological Association[2], sexual orientation refers to the enduring emotional, romantic, and sexual attractions to men, women, or both sexes including heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual categories. Homosexuality emerges naturally from pre-adolescence and is not a choice, and is considered a normal variant by the scientific community, which sits along a spectrum of sexual orientation[2]. There is no conclusive evidence on the causes to homosexuality; however, both nature and nurture could interact in the complex roles they play[2]. Some preliminary findings pointed to a possible biological basis on sexual orientation[21]. Although homosexuality is not a mental disorder, there still exist extensive negative attitudes toward homosexuals [2]. Specifically, there is a gap to bridge to move away from the dysfunction or disease model to studying the positive aspects of functioning of homosexuals. A shift to focusing on the positive functioning in this group of sexual minority will be a much needed effort to redress the balance. Due to the prejudice, oppression, and victimization, it is not unreasonable to speculate that homosexual individuals could have evolved to become more empathic and spiritual, although this contention is yet to be examined. One commonly held belief about gay people is that they tend to be more emotionally sensitive[13]. This heightened emotional perceptiveness could be beneficial for gay people in particular the lack of which could be costly especially in a hostile, homophobic environment. This emotional sensitivity or awareness is in some way related to empathy. Empathy refers to one’s ability to understand and respond to the observed emotional experiences of another person[4-6]. Empathy consists of the cognitive dimension (e.g., imagining or taking other’s perspective) and the emotional dimension (e.g., feeling vicariously)[4]. There has been an abundance of research on gender differences in empathy that pointed to the higher level of empathy in females compared to males[4,14,16,20]. However, results are still inconsistent concerning the differences in empathy between homosexuals and heterosexuals. In one study, Whitehead and Nokes[22] did not find a relationship between empathy and sexual orientation. Other studies though reported a higher level of empathy in homosexuals than heterosexuals[9,17]. When asked about the positive aspects of being gay or lesbian in a qualitative study, homosexuals also described greater personal insight, empathy and compassion such as for those who are oppressed among others[15].The spirituality of gay people is also a relatively unexplored area. Spirituality is related to one’s sense of wholeness, purpose, meaning, authenticity,interconnectedness, and appreciation for life[3,19]. Although religion can be a channel for the expression of spirituality, it is different in the sense that religion is a standardized structure of worship with its sets of practices, beliefs, and experiences[8,19]. In many cases, religion often becomes a source of conflict in gay people’s attempt to reconcile their faith and their sexuality. This may partly explain the shift to move away from religious tenets to developing their personalized spirituality among homosexual individuals as evidenced by Halkitis et al.’s[8] finding on their stronger spiritual identities than religious identities. A study by Subhi et al[18] from Malaysia examined the intrapersonal conflict of Christian homosexuals with their religion, who reported their experiences of depression, guilt, anxiety, suicidal thought, and alienation. Nonetheless, spiritual fulfillment is an important part of the lives of gay people as a result of the many challenges and oppression they have to face[8,19]. Tan[19] found that homosexual individuals reported a high level of spiritual well-being. However, Tan’s study did not include heterosexual sample for a direct comparison to be made. One study on gender differences in spirituality has also shown that women reported higher level of spirituality compared to men[3]. It would remain to be established if such differences would also exist between homosexual and heterosexual individuals. With that in mind, this study aimed to study the positive aspects of functioning in gay people (in this study, homosexual males) specifically empathy and spirituality by providing a comparative perspective. This would also add to a more meaningful understanding on these often ignored aspects of gay people’s lives.

1.1. Research Questions

- 1) Is there a difference in the level of empathy in homosexual males compared to heterosexual males?2) Is there a difference in the level of spirituality in homosexual males compared to heterosexual males?3) Is there any relationship between empathy and spirituality in homosexual and heterosexual males?

1.2. Hypothesis

- 1) There is a higher level of empathy in homosexual males compared to heterosexual males.2) There is a higher level of spirituality in homosexual males compared to heterosexual males.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- A total of 58 homosexual males (mean age = 31.3 years, S.D. = 10.1 years) and 46 heterosexual males (mean age = 21.9 years, S.D. = 4.3 years) participated. Of the homosexual participants, 23 were from Western culture while 35 were from Eastern culture. While for the heterosexual participants, 8 identified with Western culture and 38 from Eastern culture. All participants completed an online survey on empathic and spirituality dispositions.

2.2. Procedures

- This study involved completing a set of self-reported measures and questionnaire hosted online. Questionnaires were posted for the relevant online communities randomly through the use of social networking sites, online forums, and by email invitations to various organizations and institutions. This research did not require any identification information and participants of this research would remain anonymous.

2.3. Stimuli

- 1. The Klein Sexual Orientation Grid[1]. A simplified item from the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid was used to indicate a person’s sexual orientation based on a 6-point Likert scale: 1-exclusively homosexual, 2-mainlyhomosexual, 3-little more homosexual, 4-little more heterosexual, 5-mainly heterosexual, 6-exclusively heterosexual. This is further regrouped into homosexual (scale 1-3) and heterosexual (scale 4-6) groups.2. Interpersonal Reactivity Index[4,6]. A 28 self-report measure of empathy on the four 7-item subscales: perspective taking, fantasy scale, empathic concern, and personal distress. The perspective taking scale measures the tendency to adopt the psychological view of others. The fantasy scale measures one’s tendency to identify with the feelings, thinking, and actions of fictitious characters in books, movies, or plays. The empathic concern scale measures the tendency to experience other-oriented feelings, sympathy, compassion, and selfless concern for others. The personal distress scale measures one’s own feelings of unease in response to other’s distress. Davis[4] has shown good internal reliabilities from .71 to .77 and test-retest reliabilities from .62 to .71. In the present study, internal consistency was good for personal distress, α = .77; fantasy, α = .68; empathic concern, α =.64; and moderate for perspective taking, α = .56. For each of the items, participants indicated on a 5-point Likert scale on how well it describes them from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 5 (describes me very well). A total score is then calculated for each of the subscales. 3. Measure of Spirituality. A simplified 12-item measure extracted from Kendler et al.[11] was used to assess the level of spirituality (cf. Appendix A). This modified measure was intended to indicate level of spirituality broadly rather than strictly religiosity by adapting the term “God” to include other similar connotation in line with the participant’s own spiritual leaning. In the current study, good reliability was obtained for this measure, α = .96. For each of the items, participants indicated on a 5-point Likert scale on how well it describes them from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 5 (describes me very well). A total score is then calculated.

2.4. Data Analysis

- A one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to analyze the mean differences (DVs: levels of empathy and spirituality; IV: sexual orientation) to answer research questions 1 and 2. In addition, correlational analysis was also performed to answer research question 3.

3. Results

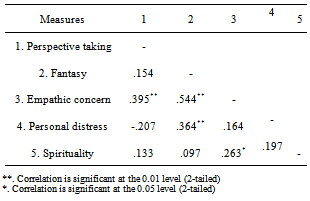

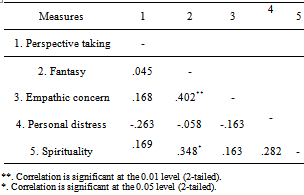

|

|

4. Discussion

- With the exception of empathic concern, this study did not find significant differences in perspective taking, fantasy, personal distress, and spirituality between homosexuals and heterosexuals (Table 1). This suggests that homosexuals and heterosexuals are equally comparable in perspective taking, fantasy, personal distress, and spirituality. Consistent with previous research[9,17], homosexuals scored significantly higher on empathic concern compared to heterosexuals. There could be possible biological and psychosocial explanations to this[12]. Biologically, there have been conjectures on the plausible influence of prenatal hormonal exposure, brain morphology, and genetics on sexual orientation[10]. The current finding is compatible with Lippa’s study[12] that found that homosexual males’ personality shifted toward female-typical directions including empathy under the agreeableness facet. The theory on the female brain as hardwired for empathizing (understanding other’s thoughts and emotions) while the male brain for systemizing (understanding and constructing systems) provides an interesting speculation that the homosexual male brain could also mirror such differentiation[7]. Social stereotypes might also predispose homosexual males to behave in a manner consistent with their sexual orientation roles such as being more sensitive [12]. Speculatively, a greater ability for empathic concern in homosexual males might be advantageous in an oppressive environment that is unsupportive and hostile toward sexual minority. The challenges and sufferings that homosexuals have had to endure could have honed their empathic concern skills. This could make them more emotionally in tuned with those of similar plight and display greater level of sympathy, non-selfish concern, compassion for unfortunate others. Contrary to expectation, there was no significant difference in spirituality between homosexual and heterosexual males in this study. Both groups scored in the medium level of spirituality. The values associated with spirituality such as developing strong connections with others, compassion, living authentically, gaining personal insights have been reported as some of the positive aspects of being a homosexual[15]. In fact, spiritual nourishment is important for homosexual individuals in facing the difficulties and challenges in life[19]. As evidenced in this study, homosexual males are no less spiritual than heterosexual males.It is interesting to note, however, that spirituality is associated with empathic concern only in homosexual males (Table 2). In contrast, spirituality is significantly correlated with fantasy only in heterosexual males in this study (Table 3). Although the causal precedence cannot be established, this suggests there is dissociation in the different facets of empathy (i.e., empathic concern and fantasy) in its linkage with spirituality between homosexual and heterosexual males. Homosexual males showed higher level of empathic concern such as feelings of sympathy and concern for unfortunate others, compassion, and non-selfish concern for others[4] that characterize their spirituality. On the other hand, fantasy has a relatively lesser emotional reaction to others and less other-oriented compared to empathic concern. Fantasy or imaginatively transposing oneself in a fictitious situation could be a proxy for one’s emotional reactions to others that might lead to helping behaviors[4]. This may be more characteristic of the nature of spirituality in heterosexual males.

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, this study lends support to previous findings that homosexual males evidenced higher level of empathic concern compared to heterosexual males. However, there are no differences in other aspects of empathy (i.e., perspective taking, fantasy, personal distress) and spirituality between homosexual and heterosexual males. There is also differential relation between different aspects of empathy with spirituality in homosexual and heterosexual males.

5.1. Limitations

- Although online study helps reduce social desirability effect and ensures anonymity which are crucial considerations in studying homosexual participants, the use of internet-based sample (a significant proportion of whom were drawn from online dating sites) in this study may not be representative of the general homosexual population. Secondly, this study did not include lesbians and bisexuals, and dichotomized the samples into homosexual and heterosexual groups because of consideration of sample size, which may not capture the continuous nature of human sexuality. Thirdly, this study did not analyze the cultural variable because of unequal sample sizes for the different categories, which may be considered for future study. Another limitation should be noted is that while the Cronbach’s alpha indicated the overall reliability of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index in this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the perspective-taking subscale was relatively low (although this might also reflect the diversity of the constructs measured).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was funded by a university grant (code: 2011-0127-106-01) from Research Management Centre, Sultan Idris Education University, Malaysia. We would like to thank Song Yee Yew, Maggie Yeo Wan Yin, and Cham Chin Hong for assistance with data collection, and an anonymous reviewer for constructive feedback. We are grateful for all participants who took part in this study.

Appendix A

- Measure of Spirituality[11]The following statements inquire about your spirituality. For each item, indicate how well it describes you. Answer as honestly as you can. Thank you.1 – Does not describe me at all2 – Does not describe me well3 – Neutral4 – Describes me well5 – Describes me very well *In some of the items below, you will see the word “God” which you may use interchangeably with other similar connotation in line with your own spiritual beliefs that you feel comfortable with, such as Higher Power, Consciousness, Universe etc.1. I ask God* to help me make important decisions.2. I feel that without God*, there would be no purpose in life.3. Spiritual experiences are important to me.4. My faith in God* helps me through hard times.5. I feel like I can always count on God*.6. I try to live how God* wants me to live.7. I consider myself to be a very spiritual person.8. My faith in God* shapes how I think and act every day.9. I help others with their religious questions and struggles.10. Every day I see evidence that God* is active in the world.11. I seek out opportunities to help me grow spiritually.12. I take time for periods of private prayer or meditation.

References

| [1] | American Institute of Bisexuality. (2007). The Klein Sexual Orientation Grid. Retrieved August 11, 2011, from http://www.bisexual.org/kleingrid.html |

| [2] | American Psychological Association. (2008). Answers to your questions: For a better understanding of sexual orientation and homosexuality. Washington, DC: APA. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/sexuality/ sorientation. pdf |

| [3] | Bryant, A. N. (2007). Gender differences in spiritual development during the college years. Sex roles, 56(11), 835-846. |

| [4] | Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113-126. |

| [5] | Decety, J., & Jackson, P. L. (2006). A social-neuroscience perspective on empathy. Current directions in psychological science, 15(2), 54-58. |

| [6] | Frías-Navarro, D. (2009). Davis' Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Unpublished manuscript. Universidad de Valencia. Spain. |

| [7] | Goldenfeld, N., Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2005). Empathizing and systemizing in males, females and autism. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 2(6), 338-345. |

| [8] | Halkitis, P. N., Mattis, J. S., Sahadath, J. K., Massie, D., Ladyzhenskaya, L., Pitrelli, K., Bonacci, M., & Cowie, S. A. E. (2009). The meanings and manifestations of religion and spirituality among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. Journal of Adult Development, 16(4), 250-262. |

| [9] | Harris, C. M. (2004). Personality and sexual orientation. College Student Journal, 38, 207-211. |

| [10] | Jenkins, W. J. (2010). Can anyone tell me why I’m gay? What research suggests regarding the origins of sexual orientation. North American Journal of Psychology, 12, 279-296. |

| [11] | Kendler, K. S., Liu, X. Q., Gardner, C. O., McCullough, M. E., Larson, D., & Prescott, C. A. (2003). Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 496-503. |

| [12] | Lippa, R. A. (2008). Sex differences and sexual orientation differences in personality: findings from the BBC internet survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 173-187. |

| [13] | Madon, S. (1997). What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles, 37, 663–685. |

| [14] | Mestre, M. V., Samper, P., Frias, M. D., & Tur, A. M. (2009). Are women more empathetic than men? A longitudinal study in adolescence. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 12(1), 76-83. |

| [15] | Riggle, E. D., Whitman, J. S., Olson, A., Rostosky, S. S., & Strong, S. (2008). The positive aspects of being a lesbian or gay man. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(2), 210-217. |

| [16] | Rueckert, L., & Naybar, N. (2008). Gender differences in empathy: The role of the right hemisphere. Brain and cognition, 67(2), 162-167. |

| [17] | Sergeant, M. J. T., Dickins, T. E., Davies, M. N. O., & Griffiths, M. D. (2006). Aggression, empathy and sexual orientation in males. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 475-486. |

| [18] | Subhi, N., Mohamad, S. M., Sarnon, N., Nen, S., Hoesni, S. M., Alavi, K., & Chong, S. T. (2011). Intrapersonal conflict between Christianity and homosexuality: the personal effects faced by gay men and lesbians. Jurnal e-Bangi, 6, 193-205. |

| [19] | Tan, P. P. (2005). The importance of spirituality among gay and lesbian individuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 49, 135-144. |

| [20] | Toussaint, L., & Webb, J. R. (2005). Gender differences in the relationship between empathy and forgiveness. The Journal of social psychology, 145(6), 673-685. |

| [21] | Weill, C. L. (2009). Nature's choice: what science reveals about the biological origins of sexual orientation. NY: Routledge. |

| [22] | Whitehead, M. M, & Nokes, K. M. (1990). An examination of demographic variables, nurturance, and empathy among homosexual and heterosexual big brother/big sister volunteers. Journal of Homosexuality, 19, 89-101. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML