-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(6): 245-254

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.08

Psychosocial Correlates of HIV-related Sexual Risk Factors among Male Clients in Southern India

Kali Prosad Roy 1, Bidhubhusan Mahapatra 2, Amit Bhanot 1, Atul Kapoor 1, S. Shankar Narayanan 1

1Population Services International (PSI), New Delhi, India

2Population Council, New Delhi, India

Correspondence to: Kali Prosad Roy , Population Services International (PSI), New Delhi, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

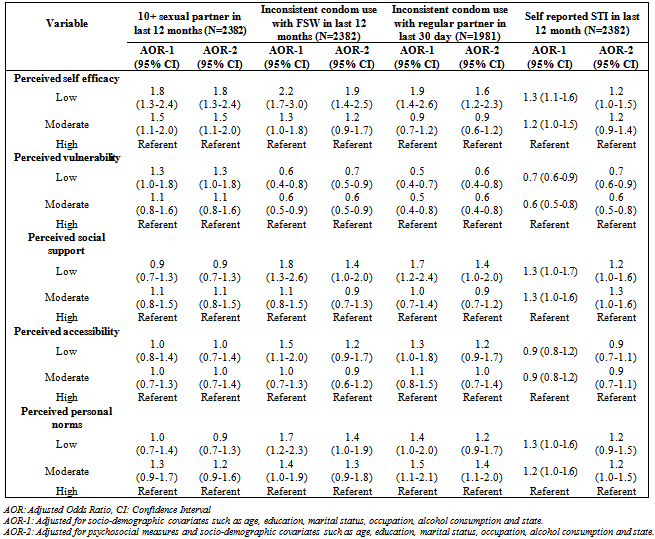

Psychosocial theories suggest that individuals’ behavior is a reflection of their intention and ability to carry out a typical behavior. This study proposes to examine the psychosocial correlates of HIV-related sexual risk factor among male clients of female sex workers (FSWs). Data were used from a cross-sectional survey, collected using two-stage sampling, conducted among 2382 clients of FSWs in four states of India in November 2008. Clients were males who had engaged in paid sex with a FSW in the 12 months preceding the survey. Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to assess the effect of different psychosocial measure on HIV-related sexual risk factors: multiple sexual partners, inconsistent condom use and self reported sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The odds of inconsistent condom use with FSWs was more among clients with low self-efficacy (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR): 2.2, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.7-3.0), low perceived social support (AOR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.3-2.6), low perceived personal norms (AOR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.2-2.3) and low perceived access to condoms (AOR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.1-2.0) than others. Similarly, experience of STI-related symptoms in the last 12 months was associated with low self-efficacy, low perceived social support and low perceived vulnerability. Findings highlight strong influence of psychosocial attitudes on HIV-related sexual risk factors among male clients of FSWs, suggesting the need for designing HIV prevention strategies to address psychosocial issues like self-efficacy, vulnerability and social support.

Keywords: Self-efficacy, Perceived Vulnerability, Social Norms, Condom, HIV

Cite this paper: Kali Prosad Roy , Bidhubhusan Mahapatra , Amit Bhanot , Atul Kapoor , S. Shankar Narayanan , "Psychosocial Correlates of HIV-related Sexual Risk Factors among Male Clients in Southern India", International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 245-254. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics of a population are considered to be the key parameter for designing HIV prevention programs. Over the year program implementers have consistently ignored the role of psychosocial perspectives of program beneficiaries[1-3]. A growing body of literature suggests that translating psychological theories into practice can help in implementing more effective HIV intervention programs[1, 3, 4]. These studies suggest that individuals’ behavior is a reflection of their intention and ability to carry out the behavior. Although the relationship between behavioral intention and actual behavior cannot be accurately measured, the intention to act can be considered as a proximate measure of behavior. Therefore, behavioral intentions can be measured in terms of attitudes, perceived social norms, perceived self-efficacy and perceived severity[5, 6]. A review of psychosocial theories related to health seeking behavior suggests that psychosocial factors like perceived vulnerability, self-efficacy, social support, accessibility and personal norms are central to most of these theories[7, 8]. Self-efficacy refers to beliefs about the ability and effort required to perform a promoted health behavior effectively[9]. According to Bandura[10], perceived self-efficacy denotes people’s belief that they can exercise control over their motivation as well as behavior. Perceived vulnerability is another factor which has received attention from researchers and program planners as it can influence health seeking behavior of individuals. According to Rogers[11], vulnerability is the risk perception of being infected with HIV if the recommended behavior is not adopted. Further, along with self-efficacy and perceived vulnerability, individual’s perception about things matters a lot while adopting a behavior[12, 13]. Empirical research shows that personal norms have strong anticipated affective outcomes to perform a behavior[7]. Personal norm is an individual’s self regulated influence on own functioning with respect to intention to perform a behavior[10]. Personal norms are primarily used to identify internalized cognitive processes that are based on an individual’s perception of the ethical correctness of performing a behavior[7]. Individuals’ effort to perform a behavior cannot be attributed to only their own attitudes and perception, but also can be due to social support and availability of services supportive to perform such behavior. In addition to personal motivation and attitudes, an individual’s social support network can act as a source of information, source of emotional and practical support, approving institution to perform a behavior[14, 15]. Personal network norms and normative beliefs about what others in the social and personal networks are actually doing are critical in adopting a new behavior. Non-availability and poor access to services can hamper the individuals’ utilization of services. Regardless of self motivation and positive social support, the perceived accessibility of a service can be detrimental in the utilization of that service.Several studies have documented a positive effect of these psychosocial factors on HIV risk behavior among general populations[16-18] including female sex workers (FSWs)[19] and their clients[20]. Empirical research investigating psychosocial correlates of condom use have found that positive attitude towards condom use[5, 21], self-efficacy[4, 5, 16, 17, 21] and perceived susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections (STIs)[22, 23] are positively correlated to condom use practice. A few studies reveal that perceived barriers to condom use and peer norms can hamper condom use practices[18, 24]. In India, the national AIDS control program has identified FSWs and their clients as two priority groups for HIV prevention interventions. The focus of such interventions are mainly providing HIV prevention education through peer educators combined with free condom distribution and treatment for STIs[25]. Recent research report suggests that in 2009 about 6% of clients of FSWs were HIV seropositives and nearly 60% reported using condom consistently with occasional FSWs[26]. A number of research studies have been undertaken in diverse settings to understand the correlates of condom use among clients of FSWs[4, 21, 27-29]. Only a few studies have been undertaken in India in this area of research; these studies have focused on understanding the socio-demographic and behavioral determinants of condom use. The role of psychosocial attitude in determining an individuals’ HIV risk behavior is yet to be explored in the Indian context. The current research is an attempt to document the relationship between different psychosocial measures and HIV risk behaviors among male clients of FSWs.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and Procedures

- A cross-sectional survey among clients of FSWs was conducted simultaneously in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra in November 2008. These states had been identified as high epidemic states by the Indian National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) prior to the year 2005[25]. The study protocol was approved by an ad-hoc ethical committee chaired by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Data were collected using a stratified two-stage cluster sampling approach; in the first stage hotspots were selected while participants were selected in the second stage. States were considered as strata except for Maharashtra, where Mumbai and rest of Maharashtra were treated as separate strata. The sampling frame was developed based on a list of hotspots of sex work activity (a place where FSWs gather to solicit clients), prepared with the help of local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) implementing the HIV intervention among clients of FSWs in the survey states. The target sample size for the survey was 2400 individuals (480 per stratum). This desired sample size was arrived at after assuming a 15% change in the behavioral indicators over time with a 95% significance level and 80% power. The primary sampling units (PSU) were the hotspots of sex work activity which were selected by probability proportional to size sampling approach. A total of 30 hotspots per strata were selected. For each PSU, the number of interviews to be conducted was fixed and interviews were conducted between 10 a.m. and 7 p.m. on all days of the week. Multiple rounds of visits were made to the same PSU in case the target number of interviews could not be completed in one visit. Trained interviewers were stationed at selected points in the hotspots and instructed to approach every fifth man passing by during a specified timeframe to avoid introducing selection bias based on the interviewer’s judgment. Interviewers were male graduates in a social science subject or statistics and had prior experience in data collection among most at risk population. Males who were 18 years or older and were involved in commercial sex (paid to have sex with an FSW) in the 12 months preceding the survey were eligible to participate in the study. Continuous monitoring mechanisms were in place to ensure smooth data collection and quality control. Each interview took approximately 45 minutes to complete.By the end of the survey, 20,850 individuals were approached; all of them were informed about the study and asked about their willingness to participate in the survey; of these 14,413 individuals were not interested in participating in the survey due to lack of time or indifference. Individuals who volunteered to participate in the survey were asked for informed consent. These individuals were further screened for their eligibility to participate in the survey. In all 3,810 individuals were found to be ineligible for the survey. Further, 245 individuals did not complete the interviews resulting in a total sample of 2,382 individuals.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Psychosocial Measures

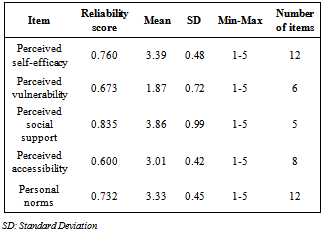

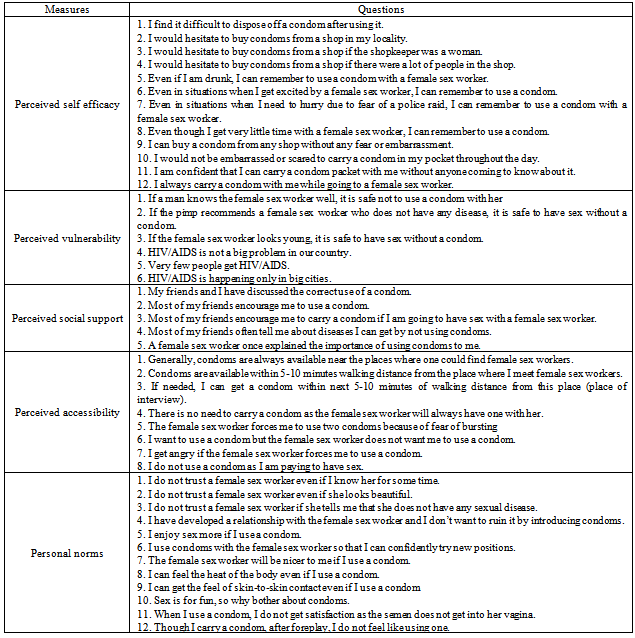

- The survey instrument was designed to collect extensive information on different psychosocial dimensions of condom use. The items measuring psychosocial attitudes in the quantitative survey were selected based on the information gathered in another qualitative research study conducted earlier in the study areas[30]. Measures of perception related to condom use and HIV/AIDS were collected using five-point Likert type scales (ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’). Some statements were worded ‘negatively’ in order to avoid artificially high consistency within the responses. Most of these statements were used in previous research on health behavior information. Information was collected for the following domains: perceived self-efficacy, perceived vulnerability, perceived social support, perceived accessibility of condoms, and personal norms. Composite scores were computed for each dimension by using the mean value of the items included in the scale. During the analysis stage, items worded ‘negatively’ were reverse coded to reflect the positive response in those items. Cronbach’s alpha values were computed for each of the scales to demonstrate the reliability of the score (Table 1). In order to examine the effect of psychosocial variables on the outcomes, these scores were further divided into three equal parts to generate a scale with the categories low, moderate and high, where low represents the lowest scores and high represents the highest scores.

2.2.1.1. Perceived Self-Efficacy

- Twelve items were used to measure perceived self-efficacy for condom use (see Appendix 1 for a complete list of items included in the scale). Typical items included: “I find it difficult to dispose off a condom after using it”, “I would hesitate to buy condoms from a shop if the shopkeeper is a woman”, “Even if I am drunk, I can remember to use a condom with an FSW” and “Even in situations when I get excited by an FSW, I can remember to use a condom”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the composite scale was 0.76 (Table 1).

2.2.1.2. Perceived Vulnerability

- Items that were meant to assess respondents’ self perception of the likelihood of contracting STI/HIV and their perception about HIV/AIDS in society were considered here. Typical items were: “If a man knows an FSW well, it is safe not to use a condom with her”, “If the pimp recommends an FSW who does not have any disease, it is safe to have sex without a condom”, “Very few people get HIV/AIDS” and “HIV/AIDS is happening only in big cities.” (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.67).

2.2.1.3. Perceived Social Support

- Social support has been assessed in terms of the kind of assistance an individual has received from friends, family members, FSWs and other stakeholders. Though eight items were presented to respondents, we considered only five items to increase the reliability of the scale (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.84). Typical items included were: “Most of my friends encourage me to use a condom”; “Most of my friends often tell me about diseases I can get by not using condoms” and “An FSW once explained the importance of using condoms to me”.

2.2.1.4. Perceived Accessibility

- Eight items were used to measure perceived barriers to condom use (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.60). Of these eight items, four were related to condom availability and the remaining four reflected barriers to condom use. Some of the items included in this measure are: “Generally, condoms are always available near the places where one can find FSWs”, “If needed, I can get a condom within the next 5-10 minutes walking distance from this place” and “I want to use a condom but the FSW does not want me to use a condom”.

2.2.1.5. Personal Norms

- Twelve items were used to assess an individual’s person norms towards condom use. Some of the items included in the scale were: “I don’t trust an FSW even if I have known her for sometime”, “I have developed a relationship with the FSW and I don’t want to ruin it by introducing condoms”, “I enjoy sex more if I use a condom” and “sex is for fun, so why bother about condoms” (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.73).

2.2.2. Outcome Measures

- The following measures of HIV-related sexual risk factors were examined in this study: inconsistent condom use with FSWs, inconsistent condom use with regular non-paying partners, multiple sexual partners and self reported STI symptoms.

2.2.2.1. Inconsistent Condom Use with FSWs

- Inconsistent condom use with FSWs was derived by taking three separate questions together that assessed “condom use in last sex (no, yes)”, “frequency of condom use in last 12 months (every time, most of the time, sometimes, very few times)” and “any occasion of not using a condom with an FSW in the last 12 months (no, yes)”. An individual was defined as an inconsistent condom user (coded as 1) with FSWs in the 12 months prior to the survey if he did not use a condom at last sex with an FSW, or did not use a condom “every time” with FSWs in the last 12 months or reported at least one instance of not using a condom with an FSW in the last 12 months; otherwise he was identified as a consistent condom user (coded as 0).

2.2.2.2. Inconsistent Condom Use with Regular Partners

- Single item questions about the number of sexual acts with regular partners (wife, fiancée and girlfriend) in the last 30 days and condom use in those sexual acts were asked. Respondents who reported condom use in all sex acts were consistent condom users with regular partners (coded as 0), else considered inconsistent condom users with regular partners (coded as 1).

2.2.2.3. Multiple Sexual Partners in the Last 12 Months

- Information on the number of sexual partners in the last 12 months was collected from each survey participant. The total number of sexual partners was regrouped into two groups based on the median split: < 10 (coded as 0), 10+ (coded as 1).

2.2.2.4. Self Reported Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Information about experience of the following five STI symptoms in the last 12 months was collected: (a) burning sensation/pain during urination, (b) thick discharge from penis, (c) ulcers/sores in the groin area, (d) scrotal swelling and pain, and (e) enlarged and/or painful inguinal lymph nodes. Experience of any of these STI symptoms in the last 12 months was considered as experience of STIs and coded as 1, else coded as 0.

2.2.3. Socio-Demographic Variables

- Information on socio-demographic variables like age, marital status and education were assessed using single item questions. Similarly, single item questions were used to collect information on occupation (recoded as unskilled worker, skilled worker, self-employed, salaried and unemployed) and alcohol consumption (never, occasional consumption, regular consumption). We used age (continuous), marital status (unmarried, married living with wife, married living without wife), education (no formal education, Class 1-9, Class 10-12, graduation or more), alcohol consumption and occupation as covariates when predicting a particular outcome with different psychosocial measures.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

- Univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to measure the strength of association in the bivariate analyses between psychosocial measures and outcome variables. Multiple logistic regression models were used to predict different HIV risk behavior variables for different psychosocial measures. Two sets of regression analyses were performed; in the first case, the effect of one psychosocial measure was measured after controlling for respondents’socio-demographic covariates; in the second case, the effect of all psychosocial measures was measured simultaneously after adjusting for socio-demographic covariates. The significance level for all statistical tests was 5% or otherwise specified. Results were presented in the form of percentages, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of point estimates. Data were analyzed using STATA 11.1.

3. Results

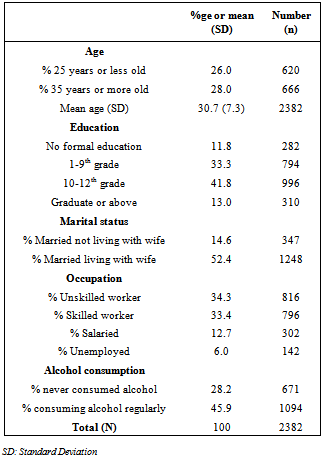

- Clients of sex workers were, on average, 30 years old (Standard deviation (SD): 7.3 years) and around one-quarter (26%) were 25 years or less (Table 2). Most respondents (88%) had some education and more than half (55%) were educated up to class 10th or more. Nearly two-thirds (67%) were married and about half (52%) were residing with their wife. About two-thirds of respondents were either unskilled workers (34%) or skilled workers (33%) and only 6% were unemployed. Twenty-eight percent did not consume alcohol and 46% consumed alcohol regularly.

|

|

4. Discussion

- This study, based on a cross-sectional survey, examined the effect of five different psychosocial measures on inconsistent condom use, multiple sexual partners and experience of STI-related symptoms among male clients of FSWs. This research adds to existing evidence and demonstrates a strong relationship between individuals’ attitudes and perceptions with HIV-related sexual risk factors. Perceived self-efficacy and perceived vulnerability to HIV were associated with practices such as multiple sexual partners, inconsistent condom use with FSWs and regular partner as well as with experience of STI-related symptoms. The current study also demonstrated that inconsistent condom use with FSWs is more likely to occur among individuals perceiving low self-efficacy, low social support, low personal norms and high perceived vulnerability. Similar associations were documented for other HIV-related sexual risk factors.Consistent with earlier studies among youths and IDUs[6, 12], our study also observed positive effect high self-efficacy on consistent condom use with FSWs and regular partners. This indicates that clients of sex workers had the ability to understand the risk associated inconsistent condom use. This, further, is supported by the post-hoc analysis which suggests that individuals with low perceived self-efficacy have higher perceived vulnerability than those with high perceived self-efficacy. Furthermore, inconsistent condom use with FSWs and regular partners was higher among individuals with high perceived vulnerability than with low vulnerability. This can be a reflection of their actual behavior, that is, those not using condoms consistently were aware of engaging in some kind of activity carrying a certain risk leading to STI/HIV infection. A similar relationship between perceived vulnerability and condom use has been documented in a recent study among sex workers[31]. Though individuals have accurately assessed their vulnerability to HIV infection, such assessments have not been translated into behavior. Behavior change communication interventions should make an additional effort to promote a positive behavior change.The study results further suggest that high perceived social support can have a positive influence on consistent condom use and reduce exposure to STI-related symptoms. The importance of a supportive environment of peers and social networks for condom use has been highlighted in past research which corroborates our study finding[14, 32-34]. This indicates that not only the personal motivation level of an individual, but also the perception that condom use is encouraged and approved by the people in the surroundings is important for consistent condom use. Another important predictor of condom use is perceived personal norms about condoms. However, perceived personal norms have no significant effect on multiple sexual relationships. This suggests that personal norms do not restrict individuals from selecting sexual partners but rather make them aware of the need to adopt safe sexual practices. The study findings also show that inconsistent condom use was higher with regular partners than with sex workers, suggesting that even with the same degree of psychosocial attitudes individuals do not use condoms with regular partners. This suggests that motivation to use condoms with sexual partners depends on whether the relationship is casual or steady in nature.

|

- There are potential limitations to our study and hence some caution is required while interpreting and drawing conclusions. First, the findings are based on a cross-sectional study and hence, the causality of measures cannot be established. For example, it is difficult to infer whether low condom use led to higher perceived vulnerability or otherwise. Second, as data collection in the survey was confined to day-time, that is, from 10a.m.-7p. m., there may be some kind of bias regarding the representativeness of the client population. A preliminary assessment before the initiation of the study suggested that profile of clients at any time of a day remain same. Third, responses on the frequency of condom use can be biased due to social desirability. In order to reduce such bias, interviews were conducted in a private location after ensuring confidentiality of the information provided. Further, we asked different questions, such as condom use at last sex and any instances when the respondent did not use a condom, to validate the responses on frequency of condom use. While generating the variable on inconsistent condom use, these checks were considered, which helped in reducing the effect of social desirability bias.The study findings presented here have important implications for policy makers on HIV interventions. First, there is a need to improve realization of risk associated with commercial sex as the study findings suggest inconsistent condom use to be associated with high risk perception. Second, the role of an individual’s social environment should not be ignored, as higher perceived acceptability of condoms in the informant’s peer group is related to more consistent condom use. Hence, efforts should be made to promote condom acceptability among male groups, in order to increase the acceptability of condom use. One possible approach to developing “environments of approval” could be to design programs reaching locally known informal leaders who can help to develop positive attitudes about condom use among their networks of young men. In addition, prevention programs should explore mechanisms for enhancement of perceived self-efficacy of individuals. A first step towards this would be to develop skills among individuals that can help them to buy condoms from either shops or vending machines placed in public places. Also, programs should continue to increase the availability of condoms at suitable locations.

5. Conclusions

- In summary, an individual’s psychosocial characteristics are part of the complex set of factors that influence unsafe sexual behaviors. This study documented positive association of perceived self-efficacy, perceived social support, perceived accessibility and perceived personal norms on use of condoms among clients of sex workers in India. Several of these psychosocial factors were also associated with the experience of STI-related symptoms and sex with multiple partners, highlighting the important role played by psychosocial factors in shaping sexual behaviors of individuals. Integrating psychosocial factors into the existing framework of HIV prevention programs can lead to better outcomes. Comprehensive interventions for preventing HIV/AIDS should include components directed to self-efficacy, perceived social support, and other psychosocial characteristics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This paper was written as part of the Knowledge Network project of the Population Council, which is a grantee of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through Avahan, its India AIDS Initiative. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Avahan. We would like thank the anonymous reviewer for the valuable feedback and suggestion.

Authors’ Contribution

- KPR conceptualized the study design and led the manuscript preparation; BM conducted analysis and literature review and assisted in conceptualization, writing of the manuscript and interpretation of the findings; AM, AK and SSN implemented the research, assisted in interpretation of study findings and manuscript writing; All authors have read and approved this version of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

- The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix: Definition of Psychosocial Measures

References

| [1] | P. Sheeran, C. Abraham, S. Orbell. "Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: a meta-analysis", Psychol Bull, vol. 125, no. 1, pp. 90-132, 1999 |

| [2] | A. Oakley, D. Fullerton, J. Holland, S. Arnold, M. France-Dawson, P. Kelley, S. McGrellis. "Sexual health education interventions for young people: a methodological review", BMJ, vol. 310, no. 6973, pp. 158-162, 1995 |

| [3] | Herman Schaalma, Gerjo Kok, Louk Peters. "Determinants of consistent condom use by adolescents: the impact of experience of sexual intercourse", Health Educ Res, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 255-269, 1993 |

| [4] | S. Wee, M. E. Barrett, W. M. Lian, T. Jayabaskar, K. W. Chan. "Determinants of inconsistent condom use with female sex workers among men attending the STD clinic in Singapore", Sex Transm Infect, vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 310-314, 2004 |

| [5] | Herman Schaalma, Leif Edvard Aarø, Alan J. Flisher, Catherine Mathews, Sylvia Kaaya, Hans Onya, Anders Ragnarson, Knut-Inge Klepp. "Correlates of intention to use condoms among Sub-Saharan African youth: The applicability of the theory of planned behaviour", Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, vol. 37, no. 2 suppl, pp. 87-91, 2009 |

| [6] | W. K. Adih, C. S. Alexander. "Determinants of condom use to prevent HIV infection among youth in Ghana", J Adolesc Health, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 63-72, 1999 |

| [7] | U. E. Pallonen, M. L. Williams, S. C. Timpson, A. Bowen, M. W. Ross. "Personal and partner measures in stages of consistent condom use among African-American heterosexual crack cocaine smokers", AIDS care, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 205-213, 2008 |

| [8] | Danuta Kasprzyk, Daniel E. Montaño, Martin Fishbein. "Application of an Integrated Behavioral Model to Predict Condom Use: A Prospective Study Among High HIV Risk Groups1", Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 28, no. 17, pp. 1557-1583, 1998 |

| [9] | C. Houlding, R. Davidson. "Beliefs as predictors of condom use by injecting drug users in treatment", Health Educ Res, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 145-155, 2003 |

| [10] | Albert Bandura. "Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of control over AIDS infection", Evaluation and Program Planning, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 9-17, 1990 |

| [11] | R. W. Rogers, Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: a revised theory of protection motivation. In Social Psychophysiology: A Sourcebook, Edited by J. T. Cacioppo and R. E Petty, Guilford Press, New York, USA, 1983 |

| [12] | Pepijn van Empelen, Herman P. Schaalma, Gerjo Kok, Maria W. J. Jansen. "Predicting condom use with casual and steady sex partners among drug users", Health Educ Res, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 293-305, 2001 |

| [13] | M. Williams, A. Bowen, M. Ross, S. Timpson, U. Pallonen, C. Amos. "An investigation of a personal norm of condom-use responsibility among African American crack cocaine smokers", AIDS care, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 218-227, 2008 |

| [14] | R. Van Rossem, D. Meekers. "Perceived social approval and condom use with casual partners among youth in urban Cameroon", BMC Public Health, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 632, 2011 |

| [15] | Albert Bandura, Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions, Edited by R. J. DiClemente and J. L. Peterson, Plenum, New York, USA, 1994 |

| [16] | Rebecca J. Cabral, Christine Galavotti, Michael J. Stark, Paul M. Gargiullo, Salaam Semaan, Janet Adams, Brian M. Green. "Psychosocial Factors Associated With Stage of Change for Contraceptive Use Among Women at Increased Risk for HIV and STDs", Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 959-983, 2004 |

| [17] | M. J. Stark, H. M. Tesselaar, A. A. O'Connell, B. Person, C. Galavotti, A. Cohen, C. Walls. "Psychosocial factors associated with the stages of change for condom use among women at risk for HIV and STDs: implications for intervention development", J Consult Clin Psychol, vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 967-978, 1998 |

| [18] | J. E. Volk, C. Koopman. "Factors associated with condom use in Kenya: a test of the health belief model", AIDS Educ Prev, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 495-508, 2001 |

| [19] | A. Adu-Oppong, R. M. Grimes, M. W. Ross, J. Risser, G. Kessie. "Social and behavioral determinants of consistent condom use among female commercial sex workers in Ghana", AIDS Educ Prev, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 160-172, 2007 |

| [20] | S. J. Semple, S. A. Strathdee, M. Gallardo Cruz, A. Robertson, S. Goldenberg, T. L. Patterson. "Psychosexual and social-cognitive correlates of sexual risk behavior among male clients of female sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico", AIDS care, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 1473-1480, 2010 |

| [21] | C. Dilorio, W. N. Dudley, J. Soet, J. Watkins, E. Maibach. "A social cognitive-based model for condom use among college students", Nurs Res, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 208-214, 2000 |

| [22] | K. Basen-Engquist. "Psychosocial predictors of "safer sex" behaviors in young adults", AIDS Educ Prev, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 120-134, 1992 |

| [23] | R. W. Hingson, L. Strunin, B. M. Berlin, T. Heeren. "Beliefs about AIDS, use of alcohol and drugs, and unprotected sex among Massachusetts adolescents", Am J Public Health, vol. 80, no. 3, pp. 295-299, 1990 |

| [24] | L. C. Ku, F. L. Sonenstein, J. H. Pleck. "The association of AIDS education and sex education with sexual behavior and condom use among teenage men", Fam Plann Perspect, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 100-106, 1992 |

| [25] | National AIDS Control Organization (NACO), "Targetted Interventions among core groups under NACP III: operational guidelines (volume 1)", NACO, Department of AIDS Control, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, 2007 |

| [26] | Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Family Health International 360 (FHI360), "Integrated Behavioral and Biological Assessment, 2009", National AIDS Research Institute, Pune, India, 2010 |

| [27] | Taiwo O. Lawoyin. "Condom use with sex workers and abstinence behaviour among men in Nigeria", The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, vol. 124, no. 5, pp. 230-233, 2004 |

| [28] | Michele R Decker, Elizabeth Miller, Anita Raj, Niranjan Saggurti, Balaiah Donta, Jay G Silverman. "Indian Men's Use of Commercial Sex Workers: Prevalence, Condom Use, and Related Gender Attitudes", JAIDS, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 240-246, 2010 |

| [29] | E Coughlan, A Mindel, C S Estcourt. "Male clients of female commercial sex workers: HIV, STDs and risk behaviour", Int J STD AIDS, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 665-669, 2001 |

| [30] | D. Ward, R. Hess, R. C. Lefebvre. "Key Components in Planning, Implementing and Monitoring a Behavior Change Communication Campaign that Increased Condom Use Among Male Clients of Sex Workers in Southern India", Cases in Public Health Communication & Marketing, vol. 2, no. pp. 105-125, 2008 |

| [31] | Anrudh K. Jain, N. Saggurti, B. Mahapatra, M. P. Sebastian, Hanimi Reddy Modugu, Shiva S. Halli, Ravi K. Verma. "Relationship between reported prior condom use and current self-perceived risk of acquiring HIV among mobile female sex workers in southern India", BMC Public Health, vol. 11, no. Suppl 6, pp. 2011 |

| [32] | D. Meekers, M. Klein. "Determinants of condom use among young people in urban Cameroon", Stud Fam Plann, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 335-346, 2002 |

| [33] | A. Akande. "AIDS-related beliefs and behaviours of students: evidence from two countries (Zimbabwe and Nigeria)", Int J Adolesc Youth, vol. 4, no. 3-4, pp. 285-303, 1994 |

| [34] | A. A. Adedimeji, N. J. Heard, O. Odutolu, F. O. Omololu. "Social factors, social support and condom use behavior among young urban slum inhabitants in southwest Nigeria", East Afr J Public Health, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 215-222, 2008 |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML