-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(6): 237-244

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.07

The Kind of Mental Health Problems and it Association with Aggressiveness: A Study on Security Guards

Affizal Ahmad , Nurul Hazrina Mazlan

Forensic Sciences Programme, School of Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 16150, Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Affizal Ahmad , Forensic Sciences Programme, School of Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 16150, Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Work-related violence has been recognized as an increasing occupational hazard in the recent years. The current study aims to identify the risk factors of mental health problems that contribute to work-related violence among security guard. A cross-sectional study was designed involving 445 security guards as the participants. Eight psychometric instruments were used to collect the data and the analyses were conducted using statistical application. The findings showed that presence of five subtypes of mental health problems were notable among the participants, considering that the population is not within psychiatric or prison settings. Two causes of mental health problems, childhood trauma experiences, and stress were found significantly related to the five subtypes of mental health problems among the participants. The five subtypes of mental health problems on the other hand were significantly related to aggression. In conclusion, stress and childhood traumas were identified as possible risk factors for mental health problems among security guard. On the other hand, mental health problems are the risk factors for aggressive acts and therefore, risk factors for workplace violence among the security guard.

Keywords: Security Guard, Mental Health Problems, Stress, Childhood Trauma, Aggression

Cite this paper: Affizal Ahmad , Nurul Hazrina Mazlan , "The Kind of Mental Health Problems and it Association with Aggressiveness: A Study on Security Guards", International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 237-244. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In recent years, awareness of violence at work which has been identified as an occupational hazard has significantly increased worldwide[1]. Many studies have been conducted to explore the effects of this alarming problem to the physical and psychological health of a person, including the employer[2-5]. However, little is known about specific occupation such as security guard. So far, researches involving security guard have been focusing on violence against the security guard[1][6], but there is not much scientific and empirical research on the involvement of security guards in aggression, violence, and crime. Security guard has been identified as one of the fastest growing occupation worldwide[7-10], thus highlighted theimportance to specifically study the population. Involvement of security guards in aggression, violence, and crime has been witnessed by several incidents such as assault of civilian by security guards including sexual assault, crime[11], as well as negligence during working[11-12]. The cause and factor that may lead to violence act among the security guard needed to be explored in order to secure the well-being at work for both the employer and the employee.Basically, security guard is defined as a privately employed person, usually uniformed, who is personally hired or paid to protect a defined area of property as well as people via various method such as direct or indirect observation[1][10][13-15]. The range of duties for security guard includes monitoring, guiding, maintaining, and most importantly, preventing crimes[14]. Various alternate terms have been used for security guard, such as security officer, private police and this includes bouncer, bodyguard, and private patrol officer[16]. Workplaces for private security guard range from a shopping mall, a company building, school to private house and even a person. Security guard is one of the occupations with high risk to get involve in incident at work such as violence and crime, which consequently affect their well-being[17]. This is due to the needs to interact with various people during working[18] as well as working pattern which often follows shift working hour rather than fixed working hour[19-20].In a study involving a sample of mentally ill security guards, stress due to high working responsibility had been identified as a probable factor that affects their work performance[21]. Many researches reported that the major source of stress in a particular job is shift work, which occupies both occupational and personal stress in term of psychological and psychosocial such as sleep disturbance, mood disturbance, personal health as well as family functioning[20-26]. It was found that there is significant relationship between stress and various dimensions of mental health, which may lead to severe mental health problems such as PTSD, and eventually may lead to violence and aggression[27-28]. The needs of the job itself require a significant higher level of stress, as proved in a study where security guard had the highest percentage (65.7%) of extensive job stress of all professions[29], and it has been proved to induce negative mental health and mood instability[20][24-25][30]. Therefore, association between stress and mental health problems can be hypothesized.Mental health is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2009) as a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community[31]. As opposed, mental health problems refers to a state of disruption in the mental health of a person. Evidence of mental health problems may contribute to the assessment and management of violence risk[32] and it has been suggested as predisposing factors foraggression[33].Study of mental health problems as a matter of fact is very common worldwide. However, so far no specific research regarding mental health problems among security guard was found. Previous literature reviews on critical incident and career burnout[6][34-35] strongly suggest that substance abuse, personality disorders, depression, and psychosis as types of mental health problems that might present among the security guards. For all four mental health problems, one of the most prevalence causes, other than stress, is childhood trauma experience[36-41]. Thus, in the present study, childhood trauma experience is hypothesized as a risk factor of mental health problems among the security guard. The objective of this study is; (i) to identify four types of mental health problem and it association withaggressiveness; and (ii) to examine the contribution of childhood trauma experiences and stress towards mental health problems among the security guards.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

- This study used a cross-sectional study design. The participants were randomly selected among bank’s security guards in Peninsular Malaysia. The total number of participants involved in this study was 445. The participants are required to be able to read and write on their own. Prior to the data collection, the participants were properly informed of the purpose of the current study and any relevant information was communicated. Any doubts were clarified and the participants were assured that they might withdraw from the current study at any time during the data collection process. Upon their agreement to participate, a respondent information sheet, a consent form, and a set of questionnaire were given to be read, signed, and answered. The average time taken to complete all instruments was 30 minutes.

2.2. Instrumentations

2.2.1. Simple Screening Instrument for Alcohol and Other Drug (SSI-AOD)

- The SSI-AOD is a screening instrument developed to asses both alcohol and drug use. It examines the symptoms of dependency for both chemicals. It contains 16 items represent consumption pattern, self-awareness of a problem, adverse physical, psychological and social effects, and physiological effects of tolerance and withdrawal[42]. The respondent will have to answers ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on each question.

2.2.2. Carlson Psychological Survey – Antisocial Tendency Scale (CPS-ATD scale)

- It was developed by Carlson (1982) based on the needs of offenders’ population. It originally contains four scales of psychological problems. For this study, only the antisocial tendency (ATD) subscale was used to screen presence of antisocial behavior among the respondent. Each question has five responses[43]. The responses are different in every question and the respondent is required to select one response that is most likely to them.

2.2.3. McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD)

- It was developed by Zanarini and colleagues (2003) specifically for screening of BPD. It contains 10 items, each with yes or no responses. The items ask about common symptoms of BPD such as impulsivity, emotion instability, irritability, lack of identity, and unstable relationship[44].

2.2.4. Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

- It is a screening instrument designed by Radloff (1977), to measure common symptoms of depression. It contains 20 items and was designed for use in the general population [45]. This instrument uses 4-point scale (0 = rarely or none of the time until 3=most or all of the time). The questions are related to certain depression symptoms such as poor appetite, sleep disturbance and loss of concentration[46].

2.2.5. Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (PSQ)

- The PSQ is a simple screening instrument designed by Bebbington and Nayani (1995) to assess psychotic symptoms. It contains five probe questions (plus secondary questions) regarding hypomania, thought insertion, paranoia, strange experiences, and hallucinations[47]. The respondent will have to answers ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on each question. Positive answer on any of the symptoms indicates a probability of having psychosis. More positive answers indicate high probability of psychosis. The secondary questions indicate more serious psychotic symptoms[48].

2.2.6. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)

- This instrument was designed by Bernstein and Finks (1998) to measures traumatic experiences during childhood. It contains 28 items and use Likert scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often and very often true). It is designed to gather information about childhood event in objective and non-evaluative terms. The instrument measures five scales; physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect. Additional three items are used for the Minimization/Denial Scale for any potential underreporting of maltreatment[49].

2.2.7. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

- The PSS was designed by Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein (1983) to detect how stressful respondents find their lives. It contains 10 items using five-point Likert scale: (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, 4 = very often[50].

2.2.8. The Aggression Questionnaire (AQ)

- The AQ is a screening instrument for aggressiveness with third grade reading level, designed by Buss and Perry (1992). It contains 29 items using 5-point Likert scale (1 = extremely not like me until 5 = extremely like me). The aggression scale consists of 4 factors; physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger and hostility[51].

2.3. Analysis

- The collected data were systematically organized and analyzed using SPSS version 19.0. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic information as well as the score for all scales used in this study. For statistical analysis, Pearson’s correlation was carried out to examine the relationship between the dependent variables (substance abuse, antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, depression, and psychosis) with possible causes (childhood trauma and stress), followed by relationship between the dependent variables with four subscales in aggression.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information

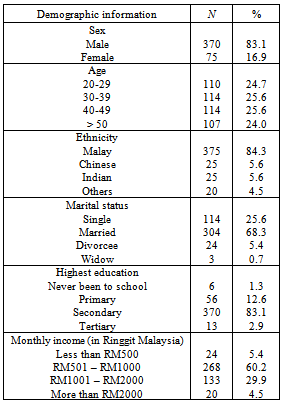

- Majority of the participant was male (83.1%). Most of the participants were within the age range of 30 to 49 (51.2%). Majority of the participant was Malay (84.3%), was married (68.3%), and had their highest education at secondary level (83.1%). For monthly income, most of them earn RM501 to RM1000 per month (60.2%). The summary of the demographic information is shown in Table 1.

|

3.2. Descriptive Results

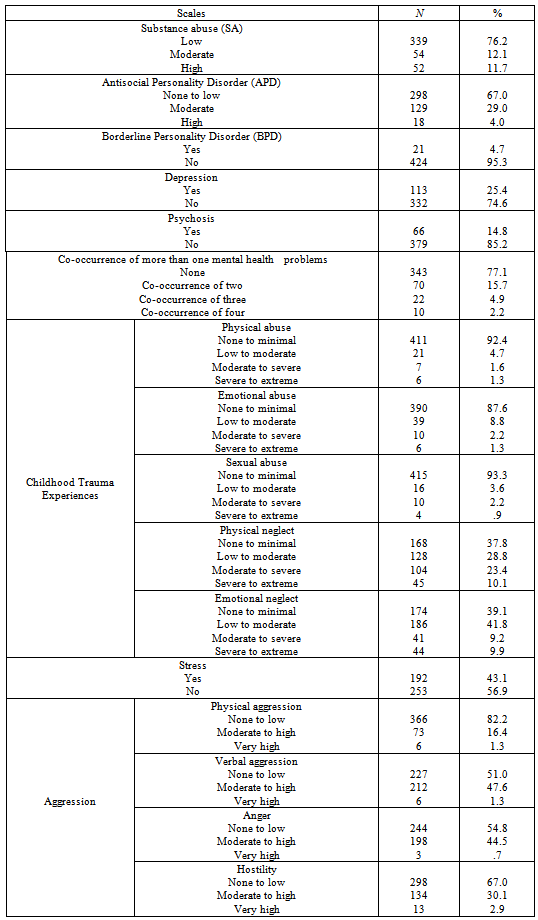

- Majority of the security guard had low level of substance abuse (SA) (76.2%). Only 11.7% of them had high SA. For antisocial personality disorder (APD) scale, majority had none to low (67%) tendency for antisocial behavior. Only 4% of this security guard had high tendency for APD. For borderline personality disorder (BPD), only 4.7% of them were screened as positive. A considerable number of participants were screened positive for depression (25.4%) and 14.8% were positively screened with psychosis. For co-occurrence of mental health problems, majority had no co-occurrence (77.1%), with the highest is co-occurrence of two (15.7%). The results for the four types of mental health problems, childhood trauma experiences, stress, and aggression are tabulated in Table 2. Overall, there is significant presence of mental health problems among the participants, considering it as the population outside the psychiatric or prison setting.

|

|

3.3. Statistical Results

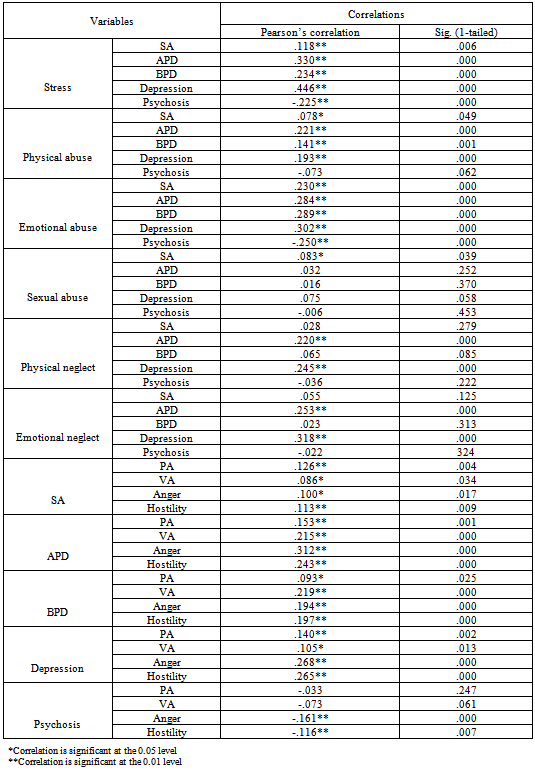

- The statistical analysis shows that there is significant relationship between stress and all the dependant variables (p< .001). The summary of the results are shown in Table 3. Substance abuse, antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, and depression are positively related to stress, whereas psychosis, which is negatively related to stress. For physical abuse, all the subtypes of mental health problems are significantly related to the subscale (p< .05), except psychosis. There is also significant relationship between emotional abuse and all the subtypes of mental health problems (p< .001). Among all the subtypes of mental health problems, only psychosis is negatively related to emotional abuse. For sexual abuse, only substance abuse was found significantly related to the subscale (p< .05). There was no significant relationship between sexual abuse and the other subtypes of mental health problems. For physical and emotional neglect, only antisocial personality disorder and depression were found significantly related to the subscales (p< .001). Relationship of all the subtypes of mental health problems with every scales of aggression (physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility) was also shown in Table 3. All the subtypes of mental health problems were found significantly related to every scales of aggression (p< .05), except for psychosis. In psychosis, only anger and hostility were found significantly related to the problems (p< .001). Both were negatively related to the psychosis. There is no significant relationship between psychosis and physical aggression, as well as verbal aggression.

4. Discussions

- As a result of increase public awareness for a more secure living condition, security guard is undoubtedly a rapidly growing profession worldwide[7-11]. Therefore, it is important to have a person with the highest state of well-being as the security personnel at the first place. The presence of mental health problems among the security guard marked the needs to properly screen an individual before he/she is hired as a security guard, especially when there is co-occurrence of the mental health problems. Co-occurrence of mental health problems increase the probability for crime and violence to occur, which is the worst situation should be avoided within this profession. Working as a security guard involves dealing with a lot of people as well as bearing trust of many people; therefore it is important for the individual working as security guard to be free of mental health problems. Having a security guard with mental health problems may significantly lead to negative consequence such as problems at the workplace. As example, people with substance abuse are exposed to various misconducts such as intoxication and negligence at work. This has happened in an international airport where two security guards were drunk and falling asleep during working[11]. High incidence of childhood trauma experiences, especially negligence showed that experiences of childhood trauma among the security guards is significant. Negligence also was found more common among the participant compared to abuse. In addition, stress was also high among the participant, which is significant to the literature that suggested high stress level often seen among security guard[29]. Profession as security guard deal with a lot of stress due to the needs of the job, such as shift work[19-20], working pattern which followed the same pattern everyday [23], and most importantly, responsibility to ensure that the job is safely done while constantly being exposed to incident[17][21]. In aggression, hostility was identified as the most common form of aggressive behavior among the security guards, followed by physical and verbal aggression. The security guard involved in the current study showed lower tendencies to act physically aggressive and they tend to be verbally aggressive rather than physically. The findings suggested that some security guard might tend to being hostile to others, probably due to the job which often being looks down by others. Significant relationship between stress and the four types of mental health problems has been demonstrated, indicate that stress significantly contribute to the occurrence of the four types of mental health problems among the security guards. Positive relationship implies that increase stress will increase the possibility to have the problems (SA, APD, BPD, and depression); whereas negative indicates that increase stress will decrease the possibility to have the problem (psychosis). In the current study, the high level of stress was shown not necessarily related to presence of psychosis among the security guards. Nevertheless, the findings confirmed that stress may induce mental health problems among security guards, as suggested by previous studies[20][24-25][30]. Therefore, stress can be established as a risk factor for mental health problems among security guard. It is recommended that to assure the well-being of security guard at work, the employer should regularly organize specific program such as management of stress or counseling talk for their employee. This is necessary to ensure the efficiency and safety of the organization’s operation. Significant relationship between childhood trauma experiences and the four types of mental health problems was demonstrated among the security guards. Both experiences of abuses and negligence showed significant contribution towards the types of mental health problems, but at different pattern. Different abusive or negligence experiences affect different types of mental health problems. As example, experiences of negligence affect only antisocial personality disorder and depression. Overall, childhood trauma experiences can be established as risk factors for mental health problems among the security guard. The findings are supported by previous studies[37][39][52], although not specifically on security guard. Thus, experience of childhood trauma should be considered when dealing with problems of mental health among security guard. The four types of mental health problems were found significantly related to aggression. These findings indicate increase in severity of the mental health problems may lead to increase in probability to act physically aggressive, verbally aggressive, angrily, or hostile among the security guard. However, psychosis was found negatively related to anger and hostility, implies that increase in severity of psychosis does not necessarily contribute to increase in probability to act angrily or hostile. Psychosis also does not contribute to physical and verbal aggression act in individual. Overall, mental health problems were confirmed that they may lead to aggressive behavior among the security guard, as suggested previously[23]. Therefore, mental health problems can be suggested as the risk factors for involvement of security guard in aggressive act, and consequently, violence and crime.

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, lack of specific study among the security guard suggests that little attention has been given to the importance of this profession in spite of its rapid growth. Risk factor that may contribute towards aggressive acts among security guards has not been studied much. Considering the significance of this profession towards a secured and protected environment, specific concern should be given towards the risk factors that may lead to occurrence of violence and crime among them. Public should aware of the issues among the security guard, especially the employer. Awareness can be very helpful in prevention and therefore, in establishment of well-being at work. Professional help such as counseling and stress management can be helpful to reduce the consequent risk among them. In the current study, stress and childhood traumas were identified as possible risk factors for mental health problems among security guard. Consequently, mental health problems were identified as the risk factors for aggressive acts and therefore, risk factors for workplace violence among the security guard.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Thank you to Universiti Sains Malaysia and the USM Fellowship for supporting this study. Thank you to all participants (security guards) who volunteered to involve in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML