-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(6): 214-225

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.04

Evaluation of a Web-Based Peer Discussion Group for Counselor Trainees

Christine J. Yeh 1, Tai Chang 2, Dorota Kowalewska-Spelliscy 3, Chris Drost 4, Devika Srivastava 5, Lillian Chiang 6

1Department of Counseling Psychology, School of Education, 2130 Fulton Street, University of San Francisco

2San Francisco, CA 94117, USA

3Department of Clinical Psychology, 1 Beach Street, Alliant International University, San Francisco, CA 94133, USA

4Licensed Psychologist Somerset Psychologists, 201-125 Somerset St. West Ottawa, ON K2W 1A8 Canada

5Counseling and Psychological Services, Montclair State University, 1 Normal Avenue, Montclair, NJ 07043,USA

6Advanced Doctoral Candidate at Fordham University, 155 West 60th Street, New York, NY 10023, USA

Correspondence to: Christine J. Yeh , Department of Counseling Psychology, School of Education, 2130 Fulton Street, University of San Francisco.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present study examined the development, content, and outcome of a two-semester Web-Based Peer Discussion Group (WBPDG) for 20 counselor trainees. Outcome measures determined that participants felt significantly more open and comfortable using the WBPDG at posttest in comparison to pretest. In addition, counselor trainees significantly reported a preference for using aliases online versus their real names in order to foster more sharing. Grounded theory[1] was used to analyze the 824 WBPDG messages revealing the following themes: Therapeutic Technique, Case Conceptualization, Professional Identity and Development, Supervision, Interpersonal Issues, and Ethics. Participation in the WBPDG also correlated with outcomes measured in face-to-face supervision. Implications for online peer supervision, practice, research, training and education in professional psychology are addressed.

Keywords: Online Discussion, Counselor Trainees, Counseling Psychology

Cite this paper: Christine J. Yeh , Tai Chang , Dorota Kowalewska-Spelliscy , Chris Drost , Devika Srivastava , Lillian Chiang , "Evaluation of a Web-Based Peer Discussion Group for Counselor Trainees", International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 214-225. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The use of the Web, Internet and E-mail in training, practice, education, and supervision settings has potential benefits for clients, psychologists, counselor trainees, and supervisors[2],[3],[4],[5]. In some models, messages are posted on a listserv where peers can offer a different types of feedback on professional issues, concerns, clients, and cases[3],[6],[7],[8]. Counselor trainees have the opportunity to send messages at any time and still participate actively in thediscussion[9],[10],[11]. Feedback and reflection for trainees are enhanced because more time is given to compose thoughts and reactions in discussions[11]. In addition, self-monitoring through Internet discussion is easily accomplished[12] and may improve when a peer group setting is available[13] In this project, we evaluated the content, usage, reactions, and efficacy of a year-long content, usage, and efficacy of a year-long Web-Based Peer Discussion Group (WBPDG) for counselor trainees. The use of the Web in professional psychology is underexplored and strengths and weaknesses of a WBPDG have yet to be identified.An important question to ask when considering the impact of a WBPDG is whether such groups can assist in the supervision process for counselor trainees. In fact, many potential qualities found in Web-based peer communities are vital factors found in peer supervision groups.Specifically, members of online peer support groups share emotional support and advice[11]. Moreover, discussion forums may provide a sense of group identity that often becomes an important aspect of self for the member[14] In addition, discussion forums provide opportunities for participants to share questions, seek advice, and share techniques, which may impact real life behavior[14].

1.1. Self-Disclosure and Anonymity

- Web-based bulletin boards bring a sense of anonymity that may be useful in counselor trainees’ discussions of their fieldwork experience.WBPDGs may create an alternative space[6],[7] that allows individuals to feel less inhibited, more honest, and more assertive. Members may feel somewhat protected by using fictional identities that ensure confidentiality[11]. Such anonymity may also prompt a more reserved trainee to feel safer[14] and may increase self-disclosure. The potential for increased self-disclosure in online discussions is especially relevant given the research indicating that nondisclosure hinders the supervision process and trainee learning[15]. Trainees are often observed to be cautious and anxious when interacting with their supervisor [15],[16],[17]. Hence, anonymous online discussions may also provide opportunities for authentic interaction.The sense of anonymity that the Web can bring to counselor trainee discussions could also potentially impede clinical growth. For example, counselor trainees could feel disconnected if they do not have in person interactions with a peer group. They do not have the opportunity to read non-verbal messages in peers or practice direct confrontation. Moreover, when using a WBPDG, counselor trainees may not develop interpersonal skills (e.g. active listening, empathy, paraphrasing, summarizing) that are important in psychology practice. Hence, we developed, implemented and evaluated the use of a WBPDG, which coexisted with face-to-face supervision. This project intended to explore the content and use of such a group and sought to understand the potential peer supervisory role such a group could have.

1.2. Web-Based Peer Discussion Groups

- WBPDG could potentially augment individual and in-person group supervision in ways that are consonant with traditional peer group supervision. WBPDG, like peer group supervision, may decrease dependency on “expert” supervisors and may facilitate collaboration among colleagues[18]. Similarly, a WBPDG may also facilitate the development of consultation and supervision skills, and increase responsibility for assessing one’s own, as well as peers’, skills[19]. As in peer group supervision, WBPDG may allow individuals to observe others’ successes and failures and thus engage in vicarious learning. Counselor trainees also learn about their peers’ clients and hence, are exposed to a broader range of clients. Peers may also offer each other a variety of perspectives in terms of range of life experience and individual differences. In the peer supervision model, the teaching and evaluative components of traditional supervision are de-emphasized[19]. For counselor trainees, peer groups such as the WBPDG may also provide reassurance that others are experiencing similar feelings and concerns[18]. Counselor trainees may then feel as though their concerns are shared among other peers and not just personal[20]. Although group supervision is widely practiced, and the number of peer supervision groups is expected to grow[21], this type of supervision is poorly understood[22]. In addition, researchers have found[23] that professional psychological associations need to develop guidelines for psychologists’ use of theInternet for psychological services. Moreover, other writings[24] suggest that professional psychology needs to integrate creative, flexible, and practical approaches to training in order to adapt to the uncertain future of practice. With this in mind, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a WBPDG for counselor trainees over the course of two consecutive academic semesters. We then analyzed the content, process, and impact of this group on counselor trainees using Grounded Theory[1], the Web-Based Peer Discussion Group Questionnaire (WBPDGQ) before the after the group, and an analysis of counselor trainees’ usage of the group.

2. Research Questions and Related Hypotheses

- Due to the limited research on Web-based discussion groups and their applications in professional psychology, the study was primarily exploratory in nature. Based on a review of the literature relating to peer group supervision and web-based discussion forums, we generated the following research questions and hypotheses for the current study. The two hypotheses related to the usage of, and participants’ reactions to, the WBPDG. Research questions related to the content of the messages posted.

2.1. Research Questions

- (1) How frequently would participants use the WBPDG? (2) During which hours would participants post messages on the WBPDG?(3) To what extent would participants feel comfortable, confident, and open using the WBPDG? (4) What types of themes would emerge on the WBPDG?(5) Would the specific content of the WBPDG change over the course of the 30-week group?(6) What is the relationship between counselor trainees’ participation in the WBPDG and their supervisor ratings (case conceptualization skills, use of counseling techniques, and use of supervision)?

3. Method

3.1. Researcher Stance

- Prior to data analysis, the first author and three raters met to discuss their biases and expectations in the research. The first author was a Counseling Psychology faculty member and supervisor of counselor trainees and had prior experience developing and facilitating web-based discussion forums. In her previous experience as a fieldwork supervisor, counselor trainees would frequently ask for more peer support and interaction to supplement the regular group supervision meetings and their onsite supervision. They described feeling frustrated that they had to wait for the next supervision meeting to discuss important developments in their practical training. They also complained that the two-hour meetings were not long enough to cover all the questions that students had. The first author expected counselor trainees to be at first resistant to using a new technology but thought that when their fieldwork began that they may see the value in being able to discuss issues, cases, and questions anytime with other beginning counselors. The raters (one male and two female) had completed at least two years of fieldwork experience. The male rater was a doctoral student in Counseling Psychology and the two female raters were Master’s level students in Psychological Counseling. All ratersexpected that the counselor trainees would not use the WBPDG at first because students are very busy and learning a new technology is often a burden. However, the three raters believed that if the system was user-friendly and convenient, it had the potential to be very helpful in discussing logistical and clinical issues. The raters were unsure how the participants would respond to the format and anonymity of the WBPDG.

3.2. Participants

- Participants included 20 counselor trainees enrolled in a Master’s degree program in Psychological Counseling at a large urban university in the Northeastern part of the United States. Seventeen (85%) of the participants owned a personal computer, all participants had regular and easy access to computer facilities at the university. Participants’ self-reported socioeconomic status was middle to middle-upper class. Ages ranged from 22-48 years (M = 27.60, SD = 5.50). In terms of racial background, 14 (70%) of the participants were White, three (15%) were Asian American, two (10%) of the participants were Latina-American, and one (5%) participant was African American. Seventeen (85%) of the participants were female and three (15%) were male. Participants were at various mental health practicum sites and each had an individual clinical supervisor located at his or her site. Six of the trainees were placed at hospitals, one was at a business setting, ten were at community agencies, and three were at mental health clinics.

3.3. Instruments

- Counselor trainees completed the Web-Based Peer Discussion Group Questionnaire before and after their participation in the group. They also completed a Demographic Questionnaire. In addition, a supervisor completed a Fieldwork Evaluation Form for each counselor trainee at the end of the academic year.

3.3.1. Demographic Questionnaire

- Demographic Questionnaire.Participants reported their age, racial background, gender, socioeconomic status, and computer/Web browser usage. Participants also reported whether or not they owned a computer.

3.3.2. Web-based Peer Discussion Group Questionnaire

- Web-based Peer Discussion Group Questionnaire (WBPDGQ). Because there are no known scales exploring counselor trainees’ reactions to using a web-based discussion forum, the WBPDGQ was developed specifically for the present study and consists of 16 questions rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The scale is based on previous scales assessing for attitudes towards internet usage[2],[26]. These previous scales also include subscales similar to the ones incorporated in the present scale. Specifically, the Online Support Group Questionnaire (OSGQ)[2] inquired about Support, Relevance of Group, Comfort in the Group and Preference for Anonymity. This scale was proven successful in measuring participants’ attitudes towards using an online support group[2]. In this scale, we added specific items that measured Comfort and Preference for Anonymity and Confidence and Openness. The Confidence subscale (4 items) assesses the extent to which individuals felt confident in the online forum for support, learning, development and effective communication among counseling interns. Sample items include, “I am confident that this discussion group could help foster my learning about issues related to counseling.”; “I am confident that the discussion forum will serve as a useful communication tool for counseling interns.” The Comfort subscale (4 items) measures the degree to which members felt comfortable using the technology and online forum to discuss topics related to their counseling experience. A sample item includes: “I am comfortable with the use of online technology in my learning.” The Openness subscale (4 items) assesses participants’ openness to using and sharing their experiences on the online forum (e.g., “I am open to sharing my experiences on the online discussionforum.”). The Preference for Anonymity subscale (4 items) referred to the extent to which participants believed the anonymous format of the WBPDGQ fostered discussion, learning, and growth (e.g., “The anonymity of the online discussion forum will foster in-depth discussion about issues related to counseling.”). Each subscale included one item that was reverse scored. The calculated Cronbach alphas for the Confidence, Comfort, Openness, and Preference for Anonymity subscales were .85, .89, .93, and .92 respectively.

3.3.3. Fieldwork Supervision Evaluation Form

- Fieldwork Supervision Evaluation Form (FSEF). The FSEF is a standard evaluation form completed by the in person supervisor to evaluate the counselor trainee across four main areas (Assessment and Evaluation Skills, Counseling Skills, Use of Supervision, and General Professional Issues) in counseling. For the purposes of this project, Assessment and Evaluation Skills were not included in the analysis since many of the counselor trainees had not yet begun the testing portion of their training. In addition, General Professional Issues were also not included since many of the items were unrelated to the WBPDG (e.g. counselor trainee is actively participating in conferences, etc). Counseling Skills comprised of 6 items (e.g., “awareness of content and process,” “establishes and maintains a safe accepting atmosphere,”) and Use of Supervision comprised of six items (e.g., “active participation in self-critique and evaluation,”). Counselortrainees are all rated on a scale where 1 = poor and 4 = excellent. In addition, supervisors may also indicate “no opportunity to observe.”

3.4. Description of the WBPDG

- The WBPDG was implemented on a Web-based discussion board designed for this project. This discussion board was based on one previously used for women with body image concerns[27] and for an Asian American male support group[2]. Participants could read and post messages 24 hours a day using any computer with a Web browser. Participants were all required to use aliases to ensure anonymity. The Web administrator, an advanced doctoral student in Counseling Psychology, kept a list matching the aliases with their real identities in a locked file cabinet. The participants were encouraged to (1) raise issues or questions, (2) respond to any of the topics listed by other members, (3) post more specific questions of their own, and (4) provide other members with feedback. The WBPDG was monitored several times a day by a Counseling Psychologist (first author) and the Web administrator. The psychologist did not know the identities of the participants. The Web administrator listed the initial instructions on the discussion forum and responded to logistical and administrative questions. The psychologist monitored the group for any emergencies. During the course of this project, there were no reported crises.The Web administrator posted ground rules relating to confidentiality, anonymity, and the use of professional language. In addition, counselor trainees were instructed not to reveal any identifying information pertaining to clients and practicum site. Since the group was intended to be solely a peer discussion group, the psychologist and Web administrator read, but did not respond to any messages for the entirety of the group to increase open discussion. The WBPDG lasted two academic semesters (30 weeks).

3.5. Qualitative Data Analysis

- Previous qualitative research on supervision in counseling psychology has used grounded theory methodology[1] to analyze supervision transcription data[28]. Grounded theory seeks to accurately describe participants’ experiences and lives through the use of codes, themes, and concepts. In Grounded Theory, researchers are not testing specific hypotheses or seeking specific themes. Rather, they are allowing the theory to emerge from the raw data. Grounded Theory has also been used to analyze group discussions[29],[30] and emphasizes building and extending existing theory[1]. Because our data collection also included the use of a pre- and post-test surveys, this approach would contribute to the “interplay of qualitative and quantitative methods”[1, p. 31] that are the framework for establishing grounded theory[30].

3.6. Basic Steps to Grounded Theory

- All of the messages (N = 842) from the WBPDG were printed and given to each of three raters who were experienced in qualitative research methodology and received weekly training in Grounded theory qualitative analysis[31]. All three raters read all the transcripts for an overview and they took notes about their emergent ideas. Next, allraters read the transcripts again and labeled categories, potential themes, and looked for common ideas, as well as differences[1],[32]. These were written in the transcript margins. Raters were open to multiple possibilities for themes and codes and made constant comparisons across participants’ responses to see if certain themes were emerging.

3.7. Saturation

- In interpreting and analyzing the data about a particular theme, a point of saturation is reached when adding additional data does not provide any new information about the theme or subtheme[1]. Because the length of the group was set and message postings were used, the saturation point was determined when counselor trainees’ responses were coded into themes and additional responses did not contribute new information about the developing themes. All of the messages were labeled and coded into themes by all three raters. They then discussed the themes until a consensus was reached. If consensus was not initially reached, the raters would begin the process again and discuss all possible themes. Because the transcripts were fairly straightforward and consisted of messages related to psychology practicum, consensus was not too difficult to obtain in the group. Next, two auditors who were counseling psychologists then reviewed the themes and codes and provided feedback to the raters. Further,the themes were shared with a participant in the group as a stability check. The raters then reviewed and incorporated the various forms of feedback from the auditors and the participant. A total of six iterations of this process resulted in 11 initial categories. Through discussion, these themes were then reduced to six. Themes are described in the results section.

4. Results

- The results include description and frequency of the content themes, trends in the WBPDG use, pre- and post-test analysis of the WBPDGQ, analysis of the FSEF, and MANOVA analysis of the content themes. The six themes that emerged from the messages are as follows: Professional Identity and Development, Supervision, Case Conceptualization, Interpersonal Issues, Ethics, and Therapeutic Technique. All three raters coded a section of 40 messages, and they achieved an acceptable level of interrater reliability (κ = .91)using Cohen's Kappa.

4.1. Frequency and Description of the Content Themes

- Frequency counts reveal the following percentages in regards to the content of the group. Specifically, topics in the group focused mostly on Therapeutic Technique (27.2%), Case Conceptualization (24.1%), Professional Identity and Development (21.5%), Supervision (17.1%), Interpersonal Issues (6.7%), and Ethics (3.3%). Below, each theme is described, subthemes are presented, and representative quotes are offered.

4.2. Content Themes

4.2.1. Therapeutic Technique

- Therapeutic Technique, included discussion about counseling interventions or questions about a specific technique. Within this theme are two subthemes: (1) Types of techniques (e.g., “At my site, I have been doing a lot of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy with my clients. However, I often feel that it is too limiting and structured - e.g. more interpersonal therapy may at times be more helpful to the client.”) and (2) Implementation of techniques (e.g. “I wonder if anyone else has had this experience and how you have dealt with it.”). One participant wrote, “While it is difficult to not give advice[to the client], try to think about the reasons motivating you to give the advice, and who it is serving. Further, maybe you could transform your advice into an open-ended question that would provoke thought in the client.”

4.2.2. Case Conceptualization

- Case Conceptualization refers to discussion relating to how a particular case is understood. The theme includes two subthemes: (1) thoughts and feelings about a case, “How do you deal with a client that is constantly missing appointments and re-scheduling….I want to keep seeing her, but I feel that it's interfering with therapy.” and (2) questions about a specific case “One of my clients (from September) JUST came out to me that she's bisexual - - and hasn't told anyone else - I'm not sure if I should refer her to a group or what to really do for her since we are at the end of our work together. Does anyone have any thoughts about this?”

4.2.3. Professional Identity and Development

- Professional Identityand Development dealt with questions, advice, or opinions in the realm of professional issues. The three subthemes are: (1) Questions about the job search, “How have people been setting up their resume?”.“I was wondering if anyone else has received a job offer from their fieldwork site and has any advice about looking for a job?” The second subtheme is Career Development, “I have been thinking about applying for a Ph.D. and exploring options after a doctoral degree.” The third subtheme is Professional Identity, “As a school counselor, we need to think about where the field is going.”

4.2.4. Supervision

- Supervision, represented any messages directly dealing with the process of supervision Subthemes include: (1) Descriptions of theSupervisor, “My supervisor is very psychodynamic in nature. He is also quite moody so it's always a mystery going into supervision” and (2) Supervision interactions, “Perhaps letting your supervisor know that you feel uncomfortable when she tells you this might alert her that it is inappropriate and she may stop”

4.2.5. Interpersonal Issues

- Interpersonal Issues were experiences that students had with people at their fieldwork site other than their clients or supervisee. Subthemes include: (1) Peer Interactions “How are people getting along with their peers, are people getting feedback from them?” “I get along with my peers quite well, and most of them are social work interns. Their orientation is a bit different, but they are in the field for the same reason that I am--they want to help people. This seems to transcend most differences that we have.” The second subtheme is (2) InterpersonalConcerns, “I have a colleague at my site who is competitive with me and I am not sure how to handle it.”

4.2.6. Ethics

- Ethics encompassed all messages with ethical content. Subthemes included: (1) Ethical Issues with Specific Clients, “My question is whether or not I will be considered unethical to accept a gift from my client?”,(2) Observed Ethical Situations, “In group supervision one day, a co-worker mentioned that she was given a gift by a client and his mother” and (3) General Ethical Discussion, “I don't think it would be a good idea to socialize with clients because there are ethical issues involved. Although we will come across clients whom we feel connected to, it is generally not wise to become friends with your clients because as the counselor, youhave a lot of power in the relationship.”

4.3. Trends in WBPDG Use

- Over the course of the academic year (seven months), an average of 120.29 messages per month and a total of 842 messages were posted. Each participant posted an average of 6.01 messages per month and 42.10 messages total (range 10-92 messages). After seven months, all 20 members were still actively participating in the group. The WBPDG messages were posted throughout the day and night, 41.1% were outside of most regular business hours (9 a.m. to 5 p.m.). Of the 842 messages sent by group members, 25.8% (N = 217) were between 9:00 a.m. and 12:59 p.m.; 33.1% (N = 279) were between 1:00 p.m. and 4:59 p.m.; 23.0% (N = 194) were between 5:00 p.m. and 8:59 p.m.; 13.1% (N = 110) were between 9:00 p.m. and 12:59 a.m.; 1.8% (N = 15) were between 1:00 a.m. and 4:59 a.m.; and 3.2% (N = 27) were between 5:00 a.m. and 8:59 a.m.

4.4. Confidence, Comfort, Openness, and Anonymity of the WBPDG

4.4.1. Pre- and Post-test Analysis of the WBPDGQ

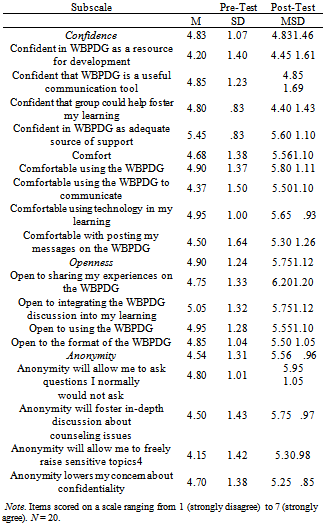

- Members of the WBPDG completed the WBPDGQ before and after their involvement in the group. The mean pre-test scores for the WBPDGQ were (M = 4.74, SD = .68) and the mean post-test scores were (M = 5.42, SD = .61), respectively. A dependent samples T-Test examined pre- and post-test differences on the overall scores of the WBPDGQ. We found that participants’ scores on the WBPDGQ significantly increased after their participation in the WBPDG over the course of two semesters t(19) = 39.80, p< .001.Pre- and post-test differences on the specific subscales of the WBPDGQ were also assessed. Table 1 displays means and standard deviations for each item as well as subscale scores on the WBPDGQ at pre- and post-test. Participants felt significantly more comfortable with the format of the WBPDG at post-test (pre-test, M = 4.68, SD =1.38; post-test, M = 5.56, SD = 1.10), t(19) = 24.98, p< .001. In addition, participants felt significantly more open to sharing sensitive issues on the WBPDG at post-test (pre-test, M = 4.90, SD = 1.24; post-test, M = 5.75, SD = 1.12 ), t(19) = 22.79, p< .001. Moreover, at the end of the WBPDG, there was a significant positive change in how participants felt the anonymous format fostered in-depth discussion and learning (pre-test, M = 4.54, SD = 1.31; post-test, M = 5.56, SD = .96), t = 25.85, p< .001. Finally, there was no change in how confident participants felt using the WBPDG to discuss concerns (pre-test, M = 4.65, SD = 1.02; post-test, M = 4.83, SD = 1.46).

|

4.4.2. Course of the WBPDG

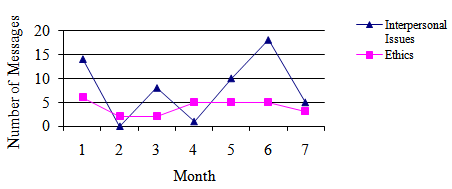

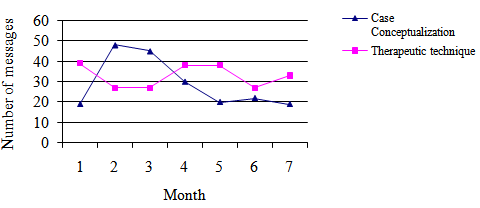

- We were also interested in examining the content of the WBPDG over the course of the seven-month group to see if counselor trainees tended to discuss different topics over time. Multivariate analysis of variance analysis (MANOVA) was used to examine whether there were any differences between months in terms of the message content across the six codes following procedures used in previous research on web-based discussion forums[2]. In other words, we wanted to know if certain themes were discussed more frequently than other themes across the course of the WBPDG. Frequency patterns for each of the codes are presented in Figures 1-2. The MANOVA, using Wilks’s Lambda to estimate the F statistic determined a significant effect for month, F(30, 3326) = 2.89, p< .001. Post hoc analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests using Tukey’s statistic revealed significant differences between months for Case ConceptualizationF(6, 835) = 5.65, p < .001 and Interpersonal IssuesF(6, 835), 6.37, p< .001.

4.4.3. Outcomes of the WBPDG

- We were also interested in seeing if individual counselor trainee’s participation in the WBPDG was significantly associated with any counseling outcomes related to Counseling Skills and Use of Supervision as indicated on the FSEF. The number of messages posted by the each counselor trainee (range = 5-92) was analyzed by calculating correlations with supervisor ratings on each of the individual items of the FSEF (1-4). Due to the high number of correlations, the p-value was set at p < .01. Pearson correlation analyses indicate several significant positive relationships between the number of messages posted on the WBPDG and positive ratings on the FSEF. Specifically, counselor trainees who posted more messages on the WBPDG were more positively rated by supervisors on only one of six items related to counseling skills: case conceptualization skills (r = .63, p <.01). However, five of the six items in the Use of Supervision Area were significant: participation in self-critique and evaluation ((r = .78, p <.01), awareness of own dynamics (r = .63, p <.01), openness to learning from supervisor (r = .73, p <.01), prepares for supervision (r = .65, p <.01), questions and challenges the supervisor (r = .63, p <.01). Participation in the WBPDG did not significantly relate to the following counseling skills: obtains adequate understanding of client problems, awareness of content and process, establishes safe and accepting atmosphere, appropriate use of counseling strategies, and understanding of counseling interactions.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- This study is the first to investigate the development, content, use, and impact of an web-based discussion group for counselor trainees at mental health sites, including hospitals, mental health clinics, and community agencies. The WBPDG was used to augment the trainees’ existing in-person supervision at their site and their group supervision in their graduate degree programs.

5.1. Convenience of the WBPDG

- Our results indicate that a large percentage (41.1%) of trainees posted messages outside of most regular business hours (9-5 P.M.), and hence, beyond the time when the trainees are usually at practicum. This finding indicates one possible advantage of using a Web-based discussion forum and it confirms previous findings documenting similar trends in use of an online support group[2]. Through a web-based discussion board, trainees had the opportunity to seek advice from, and connect with, their colleagues 24hours a day, seven days a week. The fact that many trainees posted messages at night underscores the convenience this format has for people who may be busy during regular business hours. Researchers[33] report that the limited time of in-person group supervision becomes consumed quickly and allows only some supervisees to present cases. One possible use of this WBPDG may be to continue unfinished discussions from face-to-face supervision groups.

5.2. The WBPDG as a form of Peer Group Supervision

- Another objective of this study was to uncover specific themes emerging from the discussion on the WBPDG and to see the extent to which the content of the group reflected common issues present in traditional group supervision. The six emerging themes Professional Identity and Development, Case Conceptualization, Supervision, Interpersonal Issues, Ethics, and Therapeutic Technique reflect common topics found in the research and theoretical literatureon supervision[34],[35],[36],[37].Forexample, we were very interested in seeing if counselor trainees in supervision gain awareness of their interpersonal issues and interactions. Researchers[39] found that skill, technique development, and the ability to diagnose were rated the most valuable skills among supervisors. The most prevalent theme of the discussion group was Therapeutic Technique. The subthemes (Types of techniques and Implementation of technique) represent participants willingness to offer advice about a therapeutic style to peers. This also represents the effectiveness of the WBPDG as a form of peer supervision.These subthemes highlight similar types of interactions that occur in face-to-face supervision groups[40] and exemplifies the need for counselor trainees to receive feedback as they experiment with various techniques and counseling styles. Researchers[41] further emphasize that attending to the development of practical skills is one of the factors identified for positive supervision experiences.

- The second most common theme was Case Conceptualization; one fourth of all messages related to how counselor trainees should best conceptualize their specific clients and how they feel and think about their clients. While previous research has documented the complexity of formulating a client’s case[42], the possible role of peer group supervision in this process remains unknown. Because research has reported that counselor trainees learn case conceptualization skills through understanding how others make connections with clients[43], the potential for gaining knowledge in developing case conceptualizations with a peer group is vast. Moreover, we found that more active participants in our WBPDG had higher ratings in case conceptualization skills from their supervisors, possibly indicating a link between their discussion of cases with peers on the WBPDG and their performance in supervision regarding their conceptualization of cases. The third most common theme was Professional Identity and Development, which related to counselor trainees need to discuss their job search process and career development and professional identity. This was also a common theme in previous supervision research. In their study on the use of the Internet for group discussion by rehabilitation counseling masters’ degree students,[25] found that participants used the forum to discuss professional issues. In reading the various discussions, the WBPDG seems to offer a supportive and open space for difficult discussions about one’s identity and development as a professional counselor. In particular, it seems that peers can provide validation and points of connection since they are going through similar experiences in terms of their career development and professional identity. For example, one student wrote: “I have problems with looking too young. I work in a college setting. When students come to see me, they always ask the secretary whether I am the counselor. Sometimes, I feel that they do not take me seriously. Even some staff members mistakenly think that I am a student there. I have tried to wear suits to look more professional but it did not help.” This student received numerous supportive responses reflecting similar experiences. Specifically, one student wrote:“I think what you are experiencing is probably normal for beginning counselors. I am wondering if this is your first time doing direct practice. When I started working as a counselor 2 years ago, I had a similar experience. I was working with women much older than me. Some clients actually asked me my age and suggested that I was too young to understand their experiences. With supervision, I realized I was feelings very young and inexperienced myself and that was why I was uncomfortable with the age issue. I began confronting the issue when I sense my clients had feelings about it. I would ask why it was important to know my age and explore their feelings around it. This provided some good therapeutic material. And I can tell you that with time the age issue has decreased. Now it almost never comes up and I think that has a lot to do with my confidence and experience. So I would say to give yourself time to gain confidence, discuss it in supervision, and address the issue with clients as it comes up in session. These things helped me tremendously. And I agree with others who say it is more important how you act than how you look. Good luck!!!”Supervision was the fourth most common theme discussed by the trainees. Participants were able to discuss concerns and issues related to supervision and their relationship with individual supervisors because of the anonymous and supportive format of the WBPDG. Such anonymity allowed counselor trainees to discuss complex relationship dynamics with their supervisor without fear of retribution or evaluation. In fact, many of the messages concerning supervision related to the counselor trainee’s discomfort with approaching the supervisor about certain sensitive issues (such as issues related to the supervisor’s lack of multicultural competence). These messages received validation as well as strategies on how best to work with supervisors. The fifth content area identified in the WBPDG was Interpersonal Issues. As noted previously, supervision allows a supportive context in which personal and professional growth can occur[44]. Oftentimes, counselor trainees may feel that they cannot discuss interpersonal issues or concerns with their individual supervisor and must concentrate solely on clinical skills and ethics. However, we found in our WBPDG, that many counselor trainees experienced interpersonal problems related to their new site, new colleagues, and new identity as a beginning counselor. Hence, our group offered a safe forum for participants to further explore interpersonal concerns with peers and colleagues. Ethics was the final content area that emerged in the WBPDG. While only 3.3% of the messages related to ethical issues, this may represent a preference for counselor trainees to discuss more serious ethical concerns with their individual supervisors to insure proper steps are taken. Furthermore, many ethical dilemmas are handled differently depending on the rules and regulations of the specific mental health site. Hence, counselor trainees may seek advice from colleagues or supervisors at their specific site to verify that the correct procedures are followed.While many of the core topics discussed in the supervision literature were represented in our main themes, it is still not clear if our group represented a form of peer supervision. Specifically, participants in our group only posted 6 messages a month or 42 messages for the course of seven months. If we think about a typical peer supervision model, do counselor trainees speak up more than 6 times a month? Similarly, the messages were typically only a few sentences long (3-5 sentences). Is this typical of student questions in face-to-face supervision? Or are interactions more in-depth? Did the WBPDG represent other definitions of group supervision?

5.3. Definition of Supervision

- Supervision is an important component of most training programs for counselortrainees[45]. The literature on supervision[21] has previously defined group supervision as “the regular meeting of a group of supervisees with a designated supervisor, for the purpose of furthering their understanding of themselves as clinicians, of the clients with whom they work, and/or of service delivery in general, and who are aided in this endeavor by their interaction with each other in the context of group process” (p. 111). Althoughpeer supervision has received only modest coverage in the literature[21], students and professionals who have used this method tend to have favorable views. In the peer supervision model, the traditional hierarchical relationship between supervisor and student is deconstructed and all participants have equal levels of experience and expertise[20],[46]. While members of the WBPDG had equal status and enhanced each other’s understanding of the therapeutic process and related issues, the above definition also highlights the importance of group process. Group process may have been limited in our group due to the lack of in person interaction and lack of immediacy in conversation.

5.4. Comfort, Openness, and Preference for Anonymity

- The present study also supports previous findings in terms of counselor trainees’ level of comfort, openness, and preference for anonymity[2],[25],[5]. Our results show increases in the degree to which participants felt comfortable with the format of the WBPDG, felt open to sharing sensitive issues, and felt the anonymous format fostered in-depth discussion and learning about counselling practice. The trainees’ confidence level about the discussion forum was the sole subscale that represented no change after the seven-month group. A close investigation of the subscale items indicates that the participants’ confidence in the WBPDG being a forum for learning and effective communication did not increase at post-test, whereas their confidence levels in the WBPDG being a source of their development and support, increased.It is possible that some counselor trainees felt that individual learning did not take place because they defined “learning” to mean gaining knowledge and theory, rather than growing professionally as a counselor. Future research may offer more specific understandings of the concept of learning. Instead, results reveal that the WBPDG was a beneficial place for gaining support and encouragement in trainees' development as counselors.

5.5. Changes over the Course of the WBPDG

- We were also interested in assessing if there were any trends in which topics were discussed over the course of the academic year. Case Conceptualization and Interpersonal Issues were the only two content codes that changed significantly over time when analyzing by month. The former code displayed a large increase in frequency over the first month and then gradually decreased. This change may have occurred since trainees were at the very beginning stages of their practicum training, and hence, sought out a lot of feedback from their peers and as time progressed and they became more comfortable with their skills, and with their cases, this need gradually decreased and leveled off in the final three months. The theme, Interpersonal Issues fluctuated across time but maintained close to 20 messages each month, a number that is not high when compared with other themes. The possible reason for this significant variation across time is that interpersonal issues are not necessarily subject to counselor self-efficacy or skill level hence, they may not increase or decrease over time. Rather, interpersonal issues are likely independent of other content codes and would be subject to individual variation. However, participants in our study may have been prompted to write about interpersonal issues when related messages reminded them of similar concerns. Finally, our findings reveal that counselor trainee’s active participation in the WBPDG was positively and significantly correlated with one outcome of six in terms of counseling skills (case conceptualization skills) and all six outcomes related to use of supervision (active participation in self-critique and evaluation, awareness of own dynamics, share feelings about clients, openness to learning from supervisor, prepares for supervision, and questions and challenges supervisor). There are a possible few reasons for these findings. First, it may be that the WBPDG provides a space for counselor trainees to practice asking questions and providing feedback to peers. These skills may actually enhance their participation in face-to-face supervision by giving them time to think through client questions in advance, self-reflect, and become more open to feedback. Similarly, this group may offer counselor trainees opportunities to talk through cases with peers and think through how they may conceptualize their specific clients, thus enhancing their case conceptualization skills. It is also possible, that the WBPDG did not improve counseling or use of supervision skills. Rather, it may be that counselor trainees, who tended to participate actively, may be the same students who perform well in face-to-face supervision because they are attentive, hard-working, diligent, and responsive to others. In this case, our analyses highlight positive qualities that may have already existed in our participants with higher ratings. We also found no significant association between counselor trainees’ participation and several counseling skills: obtains adequate understanding of client problems, awareness of content and process, establishes safe and accepting atmosphere, appropriate use of counseling strategies, and understanding of counseling interactions. This lack of significant findings may indicate that the WBPDG does not improve specific counseling skills, but relates to more general conceptualization strategies. New trainees require support, structured learning, and encouragement when they are first beginning to see clients[43]. A nurturing environment may be offered in WBPDG groups because trainees experience similar challenges[13]. Online peer forums may serve as a valuable medium for providing a safe and supportive setting where members are able to convey concerns, challenges, and successes[12],[48] that facilitate their professional development.Previous literature[48] has suggested that for supervision to be beneficial the development of practical skills is necessary.

6. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

- Because there were only 20 participants in the WBPDG, generalizability of the data is seriously cautioned. Although the participants were originally from various geographic locations, during the course of the project, all participants were counselor trainees at the same university. Therefore, it is important to note that our sample may not represent the experiences of other counselor trainees at other universities and locations. In addition, because most of the participants of our group were middle and middle-upper class graduate students, most owned personal computers. Our sample was also predominantly White, so it is not clear if the content of the WBPDG would have been different if the participants were more acially diverse. For instance, it is very possible that ethnic minority counselor trainees would discuss issues related to racial dynamics and White Privilege at their practicum site and in supervision. Future research studies should examine the use of WBPDGs with counselors from more diverse cultural and social class backgrounds who also have limited exposure to computers. WBPDGs are also limited because they exclude attention to nonverbal messages and cues such as facial expressions and mannerisms. These cues are often critical in interpreting peers’ intentions and feelings and are an important aspect of in-person supervision. Because this information was unavailable, counselor trainees needed to make assumptions based on the written text of the WBPDG. The WBPDG was also fairly large with 20 participants actively participating throughout the seven months. This group size may have made it difficult for more intimate interactions and intense discussions. However, previous research using a online support group with 16 active members indicated close and intimate interactions over time[2]. Hence, future research should offer smaller numbers of participants in the web-based discussion groups to test the effects of group size on group content and process. Our study is also limited by the WBPDGQ, which was developed specifically for the purposes of this study. The measure has only been used for this particular project, and there is currently no validity information available for its use. Because the sample size is relatively small, we were not able to perform exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on the scale to assess and confirm the factor structure of the scale. Future studies should seek to find validity information. However, we were able to determine that the scale had high internal consistencies and provided us with useful information to address our exploratory questions.Future studies should investigate the differences between the use of WBPDG and in-person peer supervision groups to assess the efficacy and potential benefits and limitations of web-based discussion forums in comparison to in-person groups. Additional research is also needed on various forms of online supervision such as moderated versus peer only supervision. It would also be interesting to examine supervision groups that utilize various forms of technology aside from discussion boards (such as chat rooms or listservs). Research on WBPDGs could also use different pre- and post-test measures to test for factors that may be affected by participation in WBPDGs. For example, future studies may assess pre-and post-test differences in self- reported counseling competence, counseling self-efficacy, and knowledge of ethical considerations.

7. Implications for Professional Psychology

- Our findings suggest that a web-based discussion group may offer some of the benefits also present in peer supervision. Students reported being comfortable discussing important clinical issues, such as case conceptualization, therapeutic technique, and ethics. The numerous messages containing professional development content may contribute to trainees having an increased sense of professional identity. The anonymity of this setting may have allowed trainees to be more open and comfortable in asking different types of questions. Because of the anonymity of the WBPDG, counselors in training may have also felt that the WBPDG provided a more supportive versus evaluative atmosphere.The advantage of using web-based “supervision” in psychological training is that it may be cost effective as well as accessible from remote locations to many trainees, especially to those with disabilities. It may help build a sense of community among trainees who otherwise may not have been able to share information, thoughts and feelings, or any type of feedback outside of the classroom or in supervision meetings. This factor may also make web-based communication an attractive tool that trainees could continue to use as professionals because face-to-face interaction with other professionals may be less frequent. In terms of convenience, another advantage of using web-based discussion forums for psychologists in training is that messages can be posted as well as read at any time of day or night and every message, which has been posted, remains accessible to the users. This allows the trainee time to think about and compose a response to a question. When used to augment in-person supervision, WBPDGs provide an additional opportunity for psychology trainees to discuss unanswered questions and concerns in more detail, which may help them make the most of their time with their current supervisor.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML