-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(6): 208-213

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.03

I Run to Feel Better, so why Am I Thinking so Negatively

Damian M. Stanley , Andrew M. Lane , Tracey J. Devonport , Christopher J. Beedie

School of Sport, Performing Arts and Leisure, University of Wolverhampton, Walsall, WS13BD, UK

Correspondence to: Andrew M. Lane , School of Sport, Performing Arts and Leisure, University of Wolverhampton, Walsall, WS13BD, UK.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present study investigated relationships between emotions and emotion regulation strategies employed by runners. Given that athletes and exercisers strive toward personally meaningful goals, sport and exercise settings represent a potentially fruitful context in which emotion regulation could be studied. Volunteer runners (N = 1025) reported recalled emotions experienced and emotion regulation strategies used in the hour before a recent run. Results indicated that using strategies to increase unpleasant emotions was associated with an emotional profile characterized by low scores of pleasant emotions and energetic arousal, and high scores of anger, anxiety, and other unpleasant emotions. Further, using strategies to increase unpleasant emotions was also associated with greater use of strategies to increase pleasant emotions. We argue that individuals will seek to increase the intensity of emotions, even hedonically unpleasant ones such as anger or anxiety, if they believe them useful to the attainment of a goal, thereby exhibiting instrumental emotion regulation. Practitioners should consider assessing the motivational intentions underpinning attempts at emotion regulation prior to exercise, with a particular focus on the use of strategies intended to increase hedonically unpleasant emotions, and their associated performance implications.

Keywords: Emotion, Mood, Sport, Exercise, Self-Regulation

Cite this paper: Damian M. Stanley , Andrew M. Lane , Tracey J. Devonport , Christopher J. Beedie , "I Run to Feel Better, so why Am I Thinking so Negatively", International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 208-213. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Emotion regulation is defined as “the process of initiating, maintaining, modulating, or changing the occurrence, intensity, or duration of internal feeling states and emotion-related physiological processes, often in the service of accomplishing one’s goals, p. 137” (1). A basic assumption concerning emotion regulation is that much of what we do every day is driven by the motive to experience pleasant emotions more frequently than unpleasant emotions, either in the short or the long term (2). Emotion regulation research (3, 4) tends to focus on the elucidation of strategies individuals use in the pursuit of hedonic goals such as increasing pleasant emotions (i.e., happiness, excitement, calmness), and avoiding or reducing hedonically unpleasant emotions (i.e., anger, anxiety, sadness). However, hedonic considerations might not be the only determinant of how people want to feel. The experience and expression of emotions might also be manipulated instrumentally where the goal of emotion regulation is not necessarily to feel good, but to induce changes in physiology, cognition, motivation, behavior, or the social environment that contribute to the attainment of a goal (5,6). It should be noted that there are substantial semantic issues related to the use of terms such as ‘positive’, ‘negative’, ‘pleasant’, ‘unpleasant’, ‘helpful’, ‘unhelpful’, ‘functional’ and ‘dysfunctional’ in relation to emotions. The idea that, because an emotion such as depression or anxiety is usually subjectively experienced as unpleasant, and is therefore ‘negative’, ‘unhelpful’ or ‘dysfunctional’ is questioned by many authors, especially those examining the phenomena from a psycho-evolutionary perspective (7). To remain consistent with previous research in sport, we use terms such as ‘negative’ and ‘unpleasant’ to describe emotions such as anger, anxiety, sadness, and depression, and terms such as ‘positive’ or ‘pleasant’ to describe emotions such as happiness, relief, hope and excitement. Greater clarity on these issues, although beyond the scope of the present paper, is long overdue. Research examining the ways in which emotion regulation is driven by instrumental concerns is scarce (8). Increased efforts in this direction might shed light on why individuals might seek to intensify emotions which are typically characterized as unpleasant. Tamir (8-11) has explored the ways in which individuals’ preferences for experiencing different emotions depend on the balance between their hedonic and instrumental benefits in a given context. For instance it has been reported that prior to undertaking a confrontational task, people report a greater preference for engaging in activities to instill anger rather than engaging in exciting or neutral tasks (8-9). Crucially, evidence also indicates that individuals will even choose between seeking to upregulate distinct unpleasant emotions such as anger or fear depending on which they perceive will be most applicable to the specific goal being pursued (e.g., preferring to increase fear rather than anger in the pursuit of an avoidance goal). Individuals will therefore endure, and even seek to foster, hedonically unpleasant emotions in the short term if they are perceived as fulfilling the instrumental function of aiding performance (9).A feature of the extant instrumental emotion regulation research has been the reliance on artificial contexts (e.g., computer game tasks or artificial negotiations). While this is praiseworthy in terms of being able to control for potentially confounding variables, it is possible that the emotions people experience in such contexts lack ecological validity. Demonstration of ecological validity is particularly important if findings are to apply to practice. It has been recommended the study of preferred emotions in more ecologically valid tasks and contexts such as sport and exercise (8). It is intuitive to expect that sport and exercise settings involve instrumental emotion regulation as they could include a performance element (e.g., to lift a certain weight a target number of times, or to run a certain distance within a certain time limit), and/or a competitive element in certain social contexts (e.g., to outscore an opponent, to reach a target faster than one’s training partner). It is therefore reasonable to anticipate that individuals engaging in sport or exercise might have instrumental reasons for attempting to increase discrete emotions prior to an exercise or sporting bout if they perceive them as helpful to the attainment of their particular goal (e.g., raising energy before a long run, elevating anger before attempting to lift a heavy weight).Accumulating evidence in sport psychology suggests that emotions associated with high activation (e.g., anxiety and anger) could be perceived as functional for sport performance regardless of whether they are hedonically pleasant or unpleasant (12-17). This is consistent with many theories of emotion in evolutionary psychology (7), in which the high arousal emotions are often seen as being facilitative to adaptive action (or indeed, to motion). However, when considering high activation emotions, and peoples’ deliberate self-inducement of them in the pursuit of instrumental goals, it is important to consider the potential interaction between discrete emotions, and the corresponding implications for performance. To date, research has not examined the interplay between emotions experienced, and individuals’ instrumental use of strategies to alter emotions prior to exercising. Recent research has begun to focusing on relationships between strategies used to regulate emotions and emotional states (18). To facilitate this line of investigation, a scale called the Emotion Regulation of Others and Self scale (EROS;18) was developed and validated. Niven et al (18) found that strategies to increase pleasant emotions related to pleasant emotions, and that strategies to increase unpleasant emotions associated with unpleasant emotions, that is, strategy use and emotions experienced were hedonically oriented. However, previous research evidence in athletic samples has found that when unpleasant emotions are perceived as helpful for performance they tend to be experienced concurrently with pleasant emotions (13). If an individual beliefs that certain emotions help performance, then he is likely to use strategies to get himself into that emotional state. Thus, if an individual beliefs successful performance is associated with experiencing anxiety and excitement, then it is possible that the same individual could engage in strategies to increase pleasant and unpleasant emotions. The present study used the EROS scale to examine relationships between emotions experienced and regulation strategies used by participants shortly before undertaking a run for which they had set a personal performance goal (e.g., an important training run, or a competitive run). An aim of the study was to explore the extent to which strategies intended to increase unpleasant emotions were used by a large sample of exercisers prior to exercising. Based on previous research evidence indicating that when unpleasant emotions are perceived as helpful for performance they tend to be experienced concurrently with pleasant emotions (13), we hypothesized that greater use of strategies to increase unpleasant emotions would significantly associate with greater use of strategies to increase pleasant emotions. The rationale for this hypothesis is that people see the functionality of high-activation emotions such as excitement and anxiety regardless of whether they are pleasant or unpleasant (7, 13). We further hypothesize that strategies used to intentionally increase unpleasant emotions will achieve their aim; that is, a higher use of these strategies would associate significantly with higher ratings of unpleasant emotions.

2. Mthod

2.1. Participants

- Volunteer runners (N = 1025; male n = 338, mean age = 37.98 years, SD = 9.9; female n = 687, mean age = 36.89 years, SD = 9.29) were recruited, representing levels of exercise participation ranging from recreational (58%), club (22%), regional (10%), national (6%), international (4%), and longest typical running distances ranging from 5 km to a marathon.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Emotion Regulation (18)

- developed their EROS scale to assess behavioral and cognitive strategies used to regulate emotions. In an initial validation study, they demonstrated content, factorial and criterion validity. Participants use a 5-point rating scale (i.e., 1 = “not at all”, 2 = “just a little”, 3 = “moderate amount”, 4 = “quite a lot”, 5 = “a great deal”) to respond to 12 items assessing the extent to which they use four kinds of emotion regulation strategy: behavioral strategies to increase pleasant emotions (e.g., “I did something I enjoy to try to improve how I felt”), cognitive strategies to increase pleasant emotions (e.g., “I thought about positive aspects of my situation to try to improve how I felt”), behavioral strategies to increase unpleasant emotions (e.g., “I listened to sad music to try and make me feel worse”), and cognitive strategies to increase unpleasant emotions (e.g., “I thought about my shortcomings to try and make me feel worse”). The same authors also developed a dysfunctional emotion regulation subscale representing strategies used with the intention of improving emotions but which ultimately might result in the opposite. Examples include: “I hid my feelings to try to improve how I felt” and “I took my feelings out on others to try to improve how I felt”. In the present study, participants reported the strategies they used to regulate emotions in the hour before a recent run.

2.2.2. Emotions

- Eight items from the UWIST Mood Adjective Checklist (UMACL;19) were used to assess emotion. Items assessed pleasant emotion (e.g., “calm” and “happy”), unpleasant emotion (e.g., “gloomy” and “downhearted”), unpleasant emotion associated with high activation (“anxious” and “angry”) and energetic arousal (“energetic” and “sluggish”). Items are rated on a 7-point scale (1 = “not at all”, 7 = “a great extent”).

2.3. Procedure

- Following institutional ethical approval, participants were recruited online via the website of the magazine “Runner’s World”. All participants provided consent prior to undertaking the study. Consistent with previous research, a retrospective approach was used to assess emotion regulation (4, 20). In the present study, participants were asked to recall an important recent run (i.e., one for which they had set a performance goal, in either training or competition), and to report the emotions experienced and the strategies used to regulate emotions in the hour before the run.

2.4. Data Analysis

- An initial analysis demonstrated low endorsement of strategies used to increase unpleasant emotions, with 53% of participants reporting not using these strategies (i.e., they reported a score of 1 for all 6 items). This finding is consistent with results from the original validation study for the EROS scale (18). At this stage we divided data into two groups: one group which reported having used strategies to increase unpleasant emotions, and a group which did not use such strategies. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to compare emotions and emotion regulation strategies by ‘increasing unpleasant emotion’ group. We used multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to examine relationships between emotion and emotion regulation strategy by the ‘increasing unpleasant emotion’ group.

3. Results

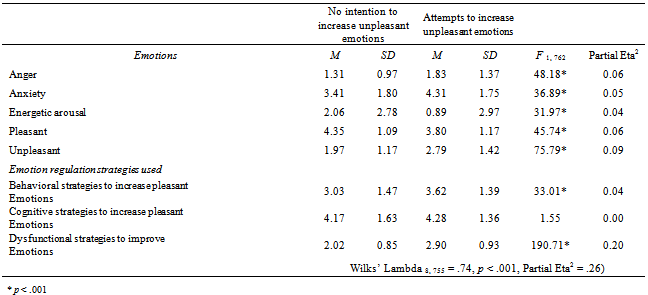

- Descriptive statistics for levels of emotions experienced, and emotion regulation strategies used by participants, are displayed in Table 1. The results are separated into two groups: runners who reported having employed strategies to increase unpleasant emotions, and those who reported no use of such strategies. As Table 1 indicates, strategies to increase unpleasant emotions were associated with higher ratings of anger, anxiety, and other unpleasant emotions, and lower ratings of energetic arousal and pleasant emotions. Runners who used strategies to increase unpleasant emotions also reported significantly greater use of behavioral strategies to increase pleasant emotions and dysfunctional strategies to increase pleasant emotions, than individuals in the group reporting no use of strategies to increase unpleasant emotions..

|

4. Discussion

- Recent work in social psychology has highlighted that people will tolerate hedonically unpleasant emotions (e.g., anger, worry, fear) if they serve an instrumental purpose such as facilitating goal attainment in a given task (8-11). Based on such findings, the present work examined the interplay between emotion regulation strategies used and emotions experienced prior to exercise. Consistent with our hypotheses, individuals who reported greater use of strategies to increase unpleasant emotions before exercising, concurrently made use of other strategies to increase pleasant emotions. Follow-up analyses indicated that individuals who used strategies to increase unpleasant emotions also reported significantly greater use of strategies intended to increase pleasant emotions than those exercisers who reported no use of strategies to increase unpleasant emotions. Results also support our second hypothesis that using strategies to increase unpleasant emotions was associated with significantly higher anxiety and anger, coupled with lower levels of pleasant emotions and energetic arousal. Therefore, it appears that using strategies to regulate emotions in the unpleasant direction achieved the intended regulatory goal.Given that some runners reported no use of strategies to increase hedonically unpleasant emotions, we split our participants into two groups for analysis: one having used strategies to increase unpleasant emotions (e.g., thinking about one’s shortcomings), and one reporting not having done so. It is interesting that when compared with the group which did not use strategies to increase unpleasant emotions, the group reporting use of emotion strategies to increase unpleasant strategies also reported significantly greater use of behavioral strategies to increase pleasant emotions prior to exercise (no differences were found in use of cognitive strategies to elevate pleasant emotions). However, while employing strategies to elevate unpleasant emotions seemed to achieve the intended goal for those using them, runners reporting no use of strategies to elevate unpleasant emotions provided significantly higher ratings of pleasant emotions experienced before the run, along with significantly higher energetic arousal. Given the nature of sport and exercise activities in which successful attainment of one’s goals is uncertain and in which individuals strive for consistent performance, it is likely that individuals achieve some successes after having experienced unpleasant emotions (e.g., successfully meeting an exercise goal having experienced anger before exercise). It is plausible that the act of mental preparation toward intensifying unpleasant emotions involves a triad of possible conflicts. The first is that such a strategy brings about successful performance and therefore, the individual sees the strategy as justifiable in future (13). The second conflict is that the strategy might result in an emotional state lasting longer than intended, especially if the athlete did not perform to her expectations. In this sense, the strategy has ultimately become ineffective, or perhaps dysfunctional. Evidence shows that poor performance associates with unpleasant emotional responses (20-22). Researchers have argued that bouts of depression are often triggered by failure to attain highly important goals, citing sports competition as a possible situation where this might occur (23). With this in mind, an internal dialogue which an individual uses to increase unpleasant emotions, even if done ostensibly to achieve performance outcomes, could undermine self-esteem if an athlete fails to achieve performance goals (23-24). The third conflict is that the individual recognizes that engaging in this process could be avoided if the individual does not participate in exercise/sport at all, leading to their withdrawal from the activity. This could be particularly applicable if seeking to upregulate unpleasant emotions for instrumental reasons before exercise instills unpleasant emotions or self-schema extending beyond exercise into people’s other everyday activities.We argue that findings from the present study contribute to the growing body of knowledge on emotion regulation. Given the notion that emotion regulation is hypothesized to be driven by a discrepancy between current and desired emotional states, some description of desired emotional states in the particular domain of interest is required. This gap will be addressed by research identifying the specific emotions exercisers want to experience prior to exercising, what they do to regulate these emotions, and the range of instrumental purposes that might be served by these emotions. For example, are some exercisers using strategies to manage their physique concerns when exercising in social environments, or are exercisers seeking to heighten anger to complete a challenging workout? A great deal of research has focused on regulatory efforts to increase hedonically pleasant emotions, an approach that appears appropriate as a long-term objective (3, 4, 24). However, consistent with the burgeoning research base in support of a more instrumental approach to emotion regulation (8-11) we argue that a purely hedonic approach to emotion regulation might not be suitable when exploring emotion regulation in many everyday settings in which individuals might wish to increase or decrease emotions (unpleasant and pleasant) in line with personal and situational demands, or the pursuit of instrumental goals. There are numerous situations in which unpleasant emotions might be desired (e.g., experiencing a degree of facilitative anxiety before an important job interview). Therefore, it is important for future research to examine desired emotional states and situational demands when examining relationships between emotions and emotion regulation.The findings of the present study have implications for applied settings, and we recommend that practitioners investigate beliefs regarding which emotions are associated with successful performance in exercise and which emotion regulation strategies are employed with these emotions as their objective. Further analysis of the motives underpinning exercisers’ emotion regulation activities will enlighten us as to whether, for example, exercisers are using emotion regulation strategies to manage their self-presentational concerns, to successfully complete arduous workouts, or to achieve competitive exercise outcomes such as upregulating anxiety in order to avoid being outperformed by others in a class scenario or social setting.

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, findings from the present study suggest that individuals’ use of emotion regulation strategies prior to exercise is complex, with exercisers using strategies to raise certain distinct pleasant emotions at the same time as strategies to increase unpleasant emotions. The burgeoning literature on instrumental emotion regulation would suggest that this interplay might be the result of exercisers altering the various distinct emotions they perceive as being useful to the pursuit of their particular goals. We found that intentionally seeking to increase unpleasant emotions was associated with higher ratings of anxiety and anger and lower ratings of pleasant emotions, including energetic arousal. We suggest that further research is needed to investigate the influence of strategies intended to increase unpleasant emotions and that practitioners should consider assessing emotion regulation strategy usage, and the perceived effectiveness of different strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The support of the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged (RES-060-25-0044: “Emotion regulation of others and self [EROS]”). We also thank Dr. Helen Lane, Dr. Paul Davis, and Catherine Swift for help with data processing.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML