-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(6): 196-207

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.02

Perceived Organizational Stressors and Interpersonal Relationships as Predictors of Job Satisfaction and Well-Being among Hospital Nurses

Olimpia Pino, Guido Rossini

Department of Neurosciences, University of Parma, Department of Psychology, B.go Carissimi, 10,43100, Parma, Italy

Correspondence to: Olimpia Pino, Department of Neurosciences, University of Parma, Department of Psychology, B.go Carissimi, 10,43100, Parma, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purposes of the present study were to examine: a) the most relevant sources of workplace pressure for nurses; b) gender and age differences in occupational stressors; c) which combination of sources of stress, ways of coping, Type A style and locus of control was the best predictor of job satisfaction and both physical and mental health; Data were collected amongst 976 nurses employed in seven public hospital in Northern Italy, who completed the Occupational Stress Indicator (OSI). Results suggested that turnover and amount of work were the most relevant sources of stress. Perceived stressors were higher for female who felt themselves less healthy than their male colleagues, which used non-working time to disperse stress. Statistical analysis produced significant differences in perceived occupational stressors among age ranges. Multivariate analysis for total sample revealed organizational factors and relationships with people the best predictors of job satisfaction and both physical and mental health, respectively. Comparisons with O.S.I. normative Italian data showed several differences in perceived sources of pressure and occupational stress outcomes. Implications of the findings and limitations of the study are discussed in terms of possible targets for action aimed to enhancing quality of the work environment relationships and nurse satisfaction.

Keywords: Occupational Stress, Nursing Stressors, Interpersonal Relationships

Cite this paper: Olimpia Pino, Guido Rossini, Perceived Organizational Stressors and Interpersonal Relationships as Predictors of Job Satisfaction and Well-Being among Hospital Nurses, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 196-207. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Given the nursing shortage that exists around the world, there has been a great deal of interest in how nurses content with stressors that exist within their professional role. Thus, a considerable amount of research has been carried out and disseminated on this topic. In the last ten years, the public health care system has undergone considerable restructuring and downsizing in order to reduce health care expenses and improve the effectiveness of the organizational system. With shrinking health care budgets and cutbacks in workforce, health care professionals are hypothesized to respond by experiencing increased levels of stress and reduced job satisfaction. Stress is a contributing factor to organizational inadequacy, high staff turnover, decreased quality and increased costs of health care, and diminished job satisfaction [1]. Hospital downsizing and restructuring tends to produce less work satisfaction and poorer psychological well-being, besides having potentially harmful effects on organizational functioning [2]. Nurses employed in hospitals that are undergoing to the reduction of expenditures and in which, as a result of restructuring, units had already been closed are more likely to experience negative environmental stress [3]. Recent research on the effects of hospital reformation demonstrates that Italian nurses perceived it as a threat to job security, and job satisfaction revealed moderate levels of burnout. Their coping strategies were primary oriented towards a direct solution of the stressful situations or avoidance, while the lack of a clear perception of institutional choices and goals indicated the organizational goals and vision as key aspects[4,5]. High levels of job satisfaction were found to be associated to a lower likelihood of both emotional exhaustion and psychiatric morbidity [6].The experience of occupational stress is clearly a multifaceted process, and relationships between stress and strain is a combination of simple and complex pathways, composed by characteristics of both environmental demands and personality dimensions[7,8]. In spite of this, several studies about the relationship between stress and nursing focused on the identification of strain sources. Some of them are related to the clinical work, while some others are consequences of the role and the organizational model within work occurs, as dealing with death and dying, turnover, shift rotation, role ambiguity or excessive workload[9-11]. Moreover, concerns about the poor quality of nursing and medical staffs, patient care poor dealings with supervisors, co-workers and physicians[13], and conflicting responsibilities between work and home [14] have been suggested as possible contributors to high stress among hospital personnel. Nevertheless, workload is considered the most noteworthy and consistent predictor of distress in nurses, as often appears in lower job satisfaction and many others stress outcomes [15]. Occupational phenomena are intimately linked to job satisfaction and both physical and mental well-being. Although job related pressures are relevant stress determinants, it is necessary to explore the influence of cognitive styles, personality dimensions, and coping strategies on stress perception. Generally, being Type A behavior and having external locus of control is the most common and unfavorable personality combination affecting job stress[16-18]. On the contrary, people with high levels of hardly personality (involvement in daily activity, a sense of control over events, and openness to change) have lower burnout scores[19]. Thus, the way in which an individual interprets objectives conditions is fundamental in determining whether or not that situation is considered as stressful. Nurses’ job satisfaction can be negatively affected by occupational stress, but this does not automatically translate itself in job dissatisfaction or mental health effects unless the individual employees inappropriate coping mechanisms, or is unable to cope with that situation [20]. Coping is considered as a moderating variable that may alter the action of stress on an outcome variable such as job satisfaction. His buffering effect will depend on how effectively problem solving or social support reduces the impact of workplace stressors, interacting on the relationship between sources of pressure and job stress [2, 12, 20]. After decades of analyzing stress and coping, Lazarus [21] points out that people exhibit a variety of coping responses influenced by sources of stress, individual’s appraisal (and successive reappraisal), and work environment’s characteristics. This transactional perspective not only simply relating organizational stressors to strains, but embraces moderating or buffering factors, including how individuals interprets objective events, attributions regarding the felt stress, and the affective outcomes on emotions[17,23]. Therefore, taking into account a combination of cognitive variable is a useful approach to study workplace stress because focuses on further arrangement of the paths through which they involve each other predicting stress outcomes[24, 25]. Locus of control might influence state strain in two different ways: directly through the well documented tendency of externals to express negative moods, but also indirectly through the perceived lack of control over one’s professional latitude which in itself not only leads to increased strain, but interacts with role problems to further enhance the level of distress [7].Among the biographical characteristics, gender may have a role in transition to distress. Gender affects each element in the stress process, by determining whether a situation is perceived as stressful, and influencing both coping responses and health implications of stress reactions [6]. Women seem to employee more than men emotional and avoidance coping styles, while show lower in detachment coping strategies; this, probably, cause somatic symptoms and psychological distress more in women than in men[26]. For women, life event and changes appears to be less controllable and more negative. Male and female may also differ in their perceptions of stress sources and outcomes, and their use of social support across stressors[27,20]. Although the literature examining the relation between gender and stress reveals conflicting findings, it argues that dual responsibilities are likely to add a significant load on nurse’s physical and mental health, and the load itself might be additional sources of work-related stress[28]. In spite of this, family support may also represent a stress-resistance factor and, hence, contribute to nurses’ job satisfaction, while work-family conflict seems to share significant relationships with psychological health[29,30].Another relevant resource related to job satisfaction/ dissatisfaction is perceived organizational support[27]. This mediating variable has influence in stress process affecting nurses’ well-being: the frequency of stressful conditions, the lack of social support from peers and the psychosocial workplace environment are the principal relevant contributors to psychosomatic health complaints in nurses[31]. Nursing staffs that scored high levels of perceived hospital support reported greater job satisfaction, lower levels of psychological burnout, and fewer psychosomatic symptoms [32]. Then, efficient clinical nursing supervision is related to lower burnout and higher job satisfaction[33], resulting in a positive effect on physical symptoms, feeling of anxiety, and in a sense of being in control of the situation [34].Occupational stress research often is lacking of a comprehensive theoretical framework and standardized measurement tools[35], which focus simultaneously on individual and organizational factors. In our study, the theoretical approach to these variables was based on Cooper’s theory of occupational stress[20,36]. This model incorporates the effects of personal characteristics (e.g. personality type, gender, cognitive styles and coping strategies) and perceived sources of pressure on an individual’s response to occupational stress elements and. This perspective considers occupational stress to be based on an individual’s negative perceptions of the workplace context and the ability to deal with them. Major sources of occupational pressure in Cooper’s model relate to stress-related outcomes, such as health problems and lowered job satisfaction.In attempt to better understand what workplace stressors, coping mechanisms and individual characteristics contribute to nurses’ well-being and job satisfaction, this study focuses on four research questions and proposes specific hypotheses designed to explore these issues. The first set of issues examines findings about workload and staff turnover as the most relevant sources of workplace pressure for nurses. As previously noted, demands and staff turnover might be expected to have a greater effect on job stress than other sources. The second group of research issues examines if gender influences occupational stress variables, in other words if women score lower than men in rational and unemotional coping styles demonstrating more physiological symptoms and psychological distress. The second hypothesis anticipates that the correlation between coping styles and stress would be stronger for women. Finally, the third set of research issues compares occupational stress variables through age ranges. Is cognitive style, locus of control and social support, the combination of independent variables that best predicts job satisfaction and both mental and physical health in nurses? Consequently, hypothesis three states that this combination would account for more variance in predicting strain then when both type of variables are regressed separately on strains, and that this greater variance accounted for would occur for all three variables.

2. Method

2.1. Nursing Sample

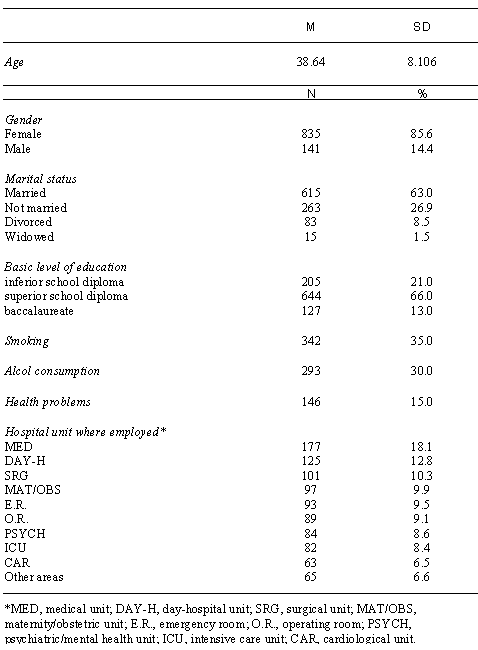

- The sample was recruited from seven hospitals in the province of Mantua (Northern Italy). An introductory meeting with hospital administrators, supervisors, and head nurses explained the purpose of the study, sampling procedure, and answered questions. Authors visited the staff providing written information about the investigations: Participants were informed that they would be asked to fill. The procedure followed was aimed at protecting both the anonymity of respondents and the privacy. Prior to implementation of the research appropriate ethical approval was obtained by hospital direction. The whole nursing population was recruited between June and October 2009, and 1009 questionnaires were collectively distributed to nurses proportional to the number in each unit. The total response was 96.7% and 976 questionnaires were returned and gathered. The sample range of age was from 22 to 63 years with an average age of 38.64 years, (SD = 8.11). Subjects, who predominately were female (85.6%, n = 835), were married or de facto (63%, n = 615). The prevailing level of education was a diploma program (66%, n = 644), while only a small percentage of them obtained baccalaureate (13%, n = 127); at the time of testing, the 35% (n = 342) was smoker and the 30% (n = 293) refer moderate use of alcohol, while 15% (n = 146) of the sample suffered from health problems in the preceding three months. A variety of clinical units within the facility provided the place of employment for these subjects, with the majority indicating that they worked in general medical area (18.1%, n = 177), followed by day-hospital (12.8%, n = 125), surgical units (10.3%, n = 101), maternity/obstetrics (9.9%, n = 97), emergency room (9.5%, n = 93), operating room (9.1%, n = 89), mental health (8.6%, n = 84), intensive care (8.4%, n = 82), cardiology (6.5%, n = 63), and other areas (6.6%, n = 65). Table 1 provides a detailed grade description for these headings. Although all the subjects were asked to list their employment years and years worked on current hospital unit, very a few provided this data. Thus, determining on average of years worked as a nurse for this sample would not provide information of significance and, therefore, was not calculated.

|

3. Measures and Procedure

- Since a variety of instruments that measure workplace stress, burnout, coping strategies, organizational climate, job satisfaction, physical and mental health, the decision to adopt the selected measure was based upon: a) whether the questionnaire appeared relevant to the Italian culture and the role of Italian hospital nurses, b) whether the instrument had been previously translated and if demonstrated acceptable reliability. The questionnaire was the Occupational Stress Indicator (OSI) [36], a self-completion questionnaire conceived and developed on the basis of the Cooper’s model [20, 36, 37]. The OSI consists of one biographical questionnaire and six scales, each of which measures different dimensions of stress. The Italian version has been validated on a sample of 534 women (M = 36, SD = 11) and 319 men (M = 34, SD = 16), with middle-high levels of education, employed in business, hospitals, factories and teaching [38]. The biographical questionnaire asked for information regarding, for example, gender, age, number of years working, general habits, or family.The OSI structure consists of six scales (with a subscale score for each of them) for a total of 167 items. Respondents were asked to rate their potential stressor on a six-point Likert-type scale. This instrument gives four independent variables (sources of stress at work, Type A behavior pattern, perceived locus of control of the work environment, use of various coping strategies), and two dependent variables (rating of both mental and physical health and job satisfaction). Independent Variables. The OSI scale “Sources of pressure” consists in six subscales that measure a variety of work stressors: “Factor intrinsic to the job” (FJ) explores workload and tasks; “Role” (FM) is concerned with how individuals perceive the expectations that others have for them and includes role ambiguity and role conflict; “Relationships with others” (FR) looks at pressures that arise from personal contacts at work; “Career and achievement” (FC) is concerned with perception of career development; “Organizational structure and climate” (FS) examines problems that may arise from bureaucracy, communication problems and morale in the organization; “Home and work interface” (FI) asks about whether home problems are brought to occupation and whether work has a negative impact on home life. These scales have split-half reliability coefficients of .36 (FJ), .63 (FM), .75 (FR), .77 (FC), .71 (FS) and .73 (FI), respectively. The OSI “Type A behavior” scale is composed of three subscales scores, which are summated to produce a total Type A score. Subscale “Attitude of living” (ATT) measures attitudinal aspects of type A such as confidence, commitment to work and its priority; “Style of behavior” (STA) assesses the behavioral aspect of Type A, including time pressure and severity of behavior; “Ambition” (AMB) measures aspect of achievement needs. These scales have split-half coefficients respectively of .33 (ATT), .43 (STA), and .25 (AMB).The OSI “Locus of control” scale consists in three subscale scores that are summated to obtain an overall perceived LOC score. The items of “Organizational forces” measure the extent to which the respondents perceive their effect over the invisible influences within the organization; “Management processes” investigate how subjects perceive their control over performances appraisal and promotions; “Individual influence” examines a more general ability to have effects within the workplace. These scales have split-half coefficients of .21 (LOCO), .13 (LOCG), and .16 (LOCI), respectively. “Coping with stress” is a scale that requires to respondents to rate the frequency of use of six kinds of stress-coping strategies. The “Social support” (CS) explores subjects’ adoption of various informal and formal support network; “Task strategies” (CP) looks at how individual organize their work into manageable chunks and forward planning, like a kind of problem solving; “Logic” (CL) addresses subjects’ embrace of an unemotional and rational approach to the situations; “Home and work relationship” (CR) is concerned with the use of non-working time to disperse stress; “Time management” (CT) measures the aspects of work organization while “Involvement” (CI) regards individuals’ job commitment and acceptance of situations. These scales have split-half coefficients respectively of .52 (CS), .22 (CP), .07 (CL), .59 (CR), .36 (CT) and .18 (CI).Dependent Variables. The OSI provides two kinds of measures, current state of health and job satisfaction. Two parts, mental and physical health, composed the scale “Current state of health”; “Mental ill health” (PSYT) taps a range of cognitive aspects of strain and “Physical ill health” (PHIT) looks at the somatic symptoms of anxiety and depression. The scale “Job satisfaction” produces five subscales scores which are summated to obtain an overall job satisfaction score; “Achievement, value and growth” (SC) examines respondents’ perceived opportunities for advancement and whether their job is rewarding; “Job itself” (SJ) measures satisfaction with the type of work; “Organizational design and structure” (SS) describes how well organisation functions; “Organizational processes” (SP) refers to perceptions of whether organisation facilitates or hinders getting things done; “Personal relationships” (SR) examines the quality of personal relationships at work. These scales have split-half coefficients respectively of .78 (PSYT), .73 (PHIT), .77 (SC), .59 (SJ), .64 (SS), .61 (SP), and .59 (SR).

3.1. Procedure

- Hospital administrators, supervisors and head nurses from the hospitals were approached about the study. The sample was made up of volunteers and no monetary compensation was given. To assure confidentiality and anonymity, the questionnaires were identified with a code placed on the packet. The questionnaires were administrated for distinct groups composed of 15-20 nurses, and the procedure was conducted in similar settings for the entire sample. Questionnaires took forty minutes to be filled.

4. Results

4.1. Data Analysis

- The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 12.0) was used for data analysis to describe occupational stress, job satisfaction, and state of health. Independent sample t - tests were carried out to assess gender differences in occupational stress variables, and to show the differences between our nursing sample and normative Italian sample. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate the effect of age on perception of workplace stressors, ways of coping, cognitive-behavioral characteristics, job satisfaction and both mental and physical health. Continuous variable age was transformed into discrete variable by grouping it in ranges, and by using t - tests to analyze their contribution to differences in occupational stress among younger, middle and higher nurses. In order to examine the relationships between the dependent and the independent variables, stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed for the total sample. The biographical items “Years worked as a nurse” and “Years worked on a current hospital unit” were excluded due to data incompleteness.

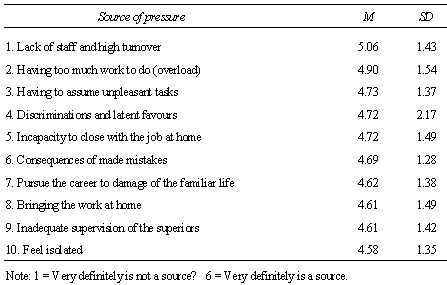

4.2. Sources of Pressure

|

4.3. Gender Differences in Occupational Stress

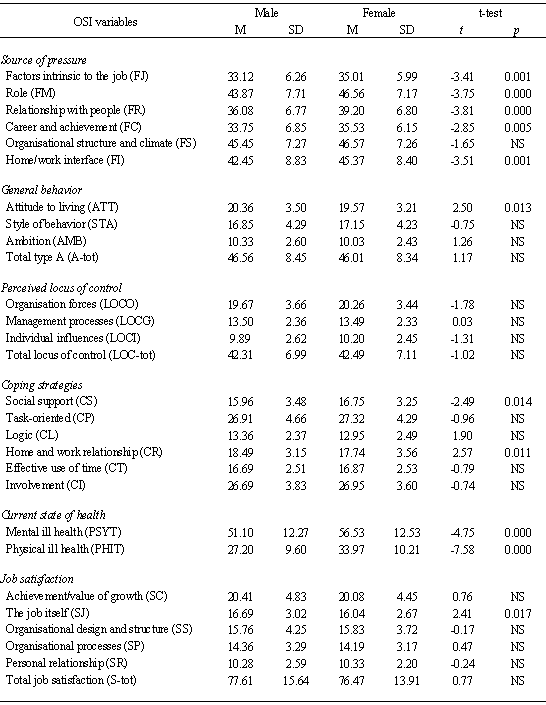

- The purpose of this comparison is to understand whether some significant differences on occupational stress variables can actually be explained in terms of gender differences. Table 3 presents the OSI scores and data obtained from independent samples t-tests carried out to test this hypothesis. Significant differences were found between men and women nurses in terms of the sources of pressure.

|

4.4. Age Differences in Occupational Stress

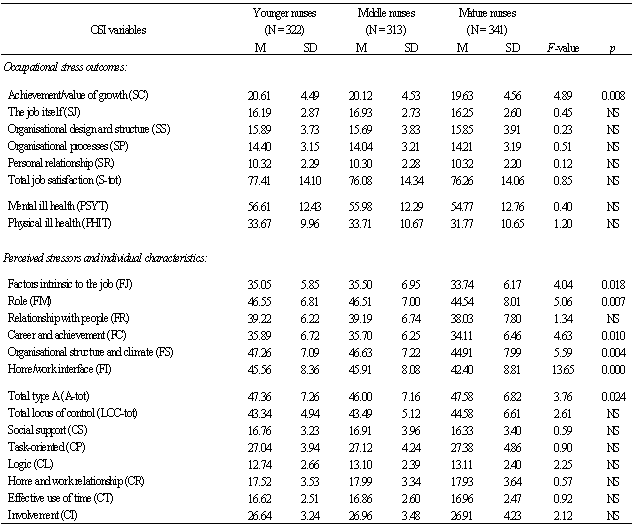

- One-way ANOVA design was used to investigate age differences in occupational stress variables in three groups of nurses (the whole sample was divided into three age ranges (see Table 4). Higher nurses showed lower job satisfaction about achievement/value of growth [F (2, 973) = 4.89 at p < 0.008], than middle and younger nurses. They also experienced a lower degree of job stress [F (2, 973) = 4.04 at p < 0.018], role stress [F (2, 973) = 5.06. at p < 0.007]; pressures form career [F (2, 973) = 4.63 at p < 0.010], organizational stress [F (2, 973) = 5.59 at p < 0.004], and home/work interface [F (2, 973) = 13.65 at p < 0.000]. While Type A behavior produces a statistical difference [F (2, 973) = 3.76 at p < 0.024], no significant differences were found among locus of control and coping strategies (see Table 4).

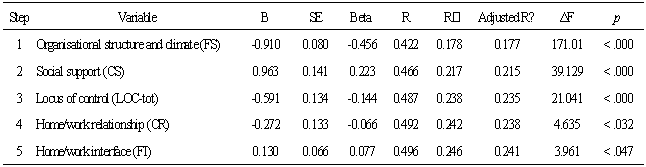

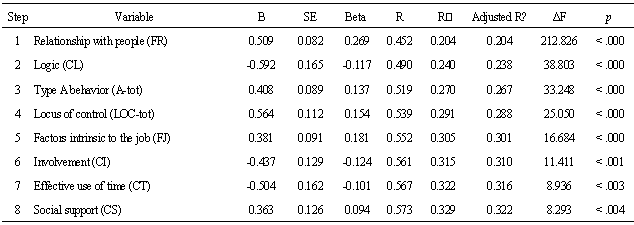

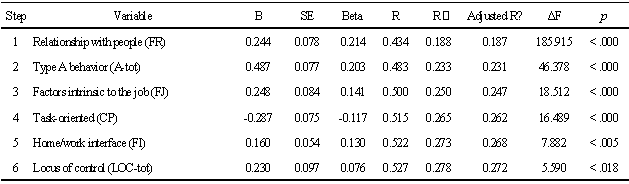

4.5. Predictors of Occupational Stress

- In order to identify the combination between independent variables (Sources of pressure, Type A behaviour, Locus of control, and Coping strategies) predict dependent variables (Job satisfaction, Mental and Physical health), a stepwise multiple-regression analysis was performed for the sample total score. The results are presented in Tables 5, 6, and 7. For each variable, the multiple regression coefficients, R², adjusted R², and the standardized regression coefficient (Beta) are displayed in order to suggest the nature of the relationship following complete substitution of all variables. Stepwise multiple regression of the independent variables versus the overall job satisfaction indicates (see Table 5) that for the total sample the 25% (24% adjusted) of the variability in job satisfaction was predicted by knowing scores on those variables, which included specific sources of occupational stress and, less importantly, coping strategies and personality variables. The specific stressor “Organizational structure and climate” entered in step one of the analysis and was the most relevant job-related predictor, explaining almost 18% (p < .000) of the total variance in job satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The negative sign in the Beta value implies that nurses who perceived more organizational stress were those less satisfied for their job. The coping strategy based on social support entered in step two and increased the explained variance of 4% (p < .000) in the job satisfaction score. Moreover, total locus of control explained further 2% (p < .000), and the negative sign of Beta coefficient means that internal locus of control is associated with satisfaction in nursing profession. All other variables failed to enter into the equation.Table 6 shows the stepwise multiple regression of the independent variables versus the overall mental health index for all the group of nurses. Eight variables, including specific stressors, coping strategies and personality dimensions were all significantly different from zero [F (14, 723) = 26,19 p < .000]. The specific stressor named “Relationships with people” entered on the first step of the regression analysis and accounted for 20% of the total equation (p < .000). The positive sign of the Beta value suggested that nurses who were at risk for mental ill health were those who perceived higher levels of interpersonal stress. Al the step two of the analysis, coping strategy named “Logic”, reported by the nurses entered the equation and added 4% (p < .000) to the variance in the dependent variable. Locus of Control subscale “Organisational forces” explained another 2% (p < .000) Findings suggest that the more nurses felt the relationships with people as stressors, the higher they reported mental ill health. Moreover, those nurses who had an external locus of control about organisational issues, displayed a Type A pattern and did not use coping strategy based on a rational approach to the problems, were more likely to have lower levels of mental health.Table 7 presents multiple regression of the independent variables versus total physical health scores. Seven steps proved to be significant in this regression [F (14, 728) = 21,66 at p < .000], altogether accounting for the 25% (24% adjusted)of the variance in physical health. It is worth noting that at step one the most important predictor of physical ill health was the same that predicted mental ill health. In fact, the variable “Relationships with people” explains 19% (p < .000) of the total variance of the dependent variable. At step two Locus of Control subscale “Organisational forces” entered to equation explaining 1,4 %, (p < .000) while the specific stressor “Home/work interface” explains a further 1,3% (p < .000) of the total variance and “Effective use of time” explains 1% (p < .000).

|

|

|

|

|

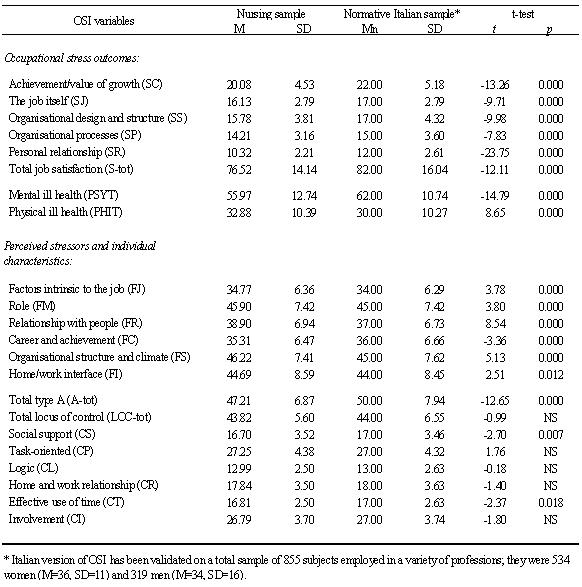

4.6. Differences between Nursing Sample and Italian Population

- O.S.I. normative data refers to a heterogeneous sample composed by different groups of professionals employed in business, hospitals, factories and educational setting [38], while our sample consists of mono-professional population. Thus, a question that arises is: does our nursing sample show any differences about occupational stress variables respect to the normative Italian sample? Table 8 presents the OSI scores obtained from means of independent samples t-tests. The results indicated important and significant differences in all occupational stress outcomes. Nursing sample shows lower scores in total job satisfaction (t = 12.11, p < .000), “Achievement/value of growth” (t = 13.26, p < .000), “The job itself” (t = 9.71, p < .000), “Organizational design and structures” (t = 9.98, p < .000), “Organizational processes” (t = 7.83, p < .000), and “Personal relationship” (t = 23.75, p < .000). Compared with normative population, nurses also show significant (p < .000) lower levels of mental ill health (t = 14.79), but higher levels of somatic symptoms (t = 8.65). There were important differences in perception of sources of stress: nursing sample manifests a higher score in “Factors intrinsic to the job” (t = 3.78, p < .000), “Role” (t = 3.80, p < .000), “Relationship with people” (t = 8.54, p < .000), “Organizational structure and climate” (t = 5.13, p < .000) and “Home/work interface” (t = 2.51, p < .012). Nurses shows lower score in “Career and achievement” (t = 3.36, p < .000) than Italian sample. There were no significant differences in terms of total locus of control, coping strategies scores revealed a lower employ of “Social support” (t = 2.70, p < .007) and “Effective use of time” (t = 2.37, p < .018) for our nurses.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- The main purpose of the present study was to examine which combination of variables was the best predictor of occupational stress in a large group of Italian hospital nurses. Data revealed, overall, that in hospitals undergoing restructuring organizational stressors and relationships with people were the most meaningful and consistent predictors of distress in nurses, as suggested from lower job satisfaction and both physical and mental state of health. As hypothesized, the most important single sources of stress perceived by the sample were turnover and workload, respectively: probably these two stressors are linked each other, in fact, the shortage of nursing staff exacerbates the problem of workload resulting in an additional amount of work. Research findings support the idea that workload is a significant stressor in nursing, associated with a variety of deleterious psychological reactions, including burnout [39].Our data confirmed the hypothesis that female nurses experienced higher frequency of stress and felt themselves less healthy than their male colleagues, but they didn’t differ in the adoption of unemotional and rational approach to the situations. Males and females differed significantly in measures of perceived sources of pressure, job satisfaction about the occupation itself and the use of two coping strategies: men adopted the home-work relationships more frequently than women who used social support as principal resource of stress managing. Thus, men took advantage better of non-working time to disperse stress, while women felt the external stressors to the work environment as an influence to occupational stress and vice-versa. Our subjects are predominately female, married or de facto: probably the overflow of family-related stress on work-related stress is greater for women than for men. The interaction between the two spheres may render the nature of women’s responsibilities heavier than men’s. Nevertheless, findings on investigations of gender differences in coping behaviors are not definitive and it is possible that other causal models better characterize the relationship between family characteristics and work responses than those assessed here. Many studies report differences in how women and men cope with stress, although these tendencies can change in certain circumstances [26]. The results of the present investigation help to fill the gaps in our knowledge about the role that work plays in our lives by providing information on the relationship between work and family life and on the extent to which men and women vary in response to specific features of their jobs and households. Given the relatively low status of women in most occupational situations, it is not surprising that women, more often than man, perceive having inadequate resources for coping with a threatening situation and also see a stressful situation as unchangeable, and tend to turn to others for support. In spite of this, knowing and managing gender differences may help to effectively motivate nurses and improve occupational well-being. No statistical differences were found among younger, middle and higher nurses in occupational stress outcomes, except for satisfaction about career. It seems that the higher nurses were less satisfied about opportunities for advancement and rewarding. Moreover, they showed lower than younger and middle nurses in every perceived stressor, save for interpersonal relationships, a factor intrinsic to the workplace environment. Perhaps, this means that in advancement of age, workplace extrinsic factors represent neither a positive stimulus nor a source of pressure for nursing career. In our research, the major predictor of job satisfaction and its subscales for the whole group was “Organizational structure and climate”: High demands such as “Inadequate control from superiors”, “Lack of information and involvement in decision–making”, and “Lack of staff and high turnover”, predicted lower job satisfaction. Others additional predictors were lack of social support, and perceived lack of control. According to these findings, the nurses who had an external locus of control, and did not use that resource of coping were more likely to show lower levels of job satisfaction under the effects of organizational stress. An external attribution as the perception of organizational controllability may affect the worker’s reaction to the stressor [17]. It’s easy to understand why those individuals who believe that they have little personal control over events or situations, and utilize or perceive the presence of social support, experience higher levels of job satisfaction. The buffering effect of social support increases the sense of personal control affecting stress and its outcomes [34]. The sources of support generally available in the work environment for nurses who are experiencing stress are support from supervisors and from coworkers (who might be also under stress), and those extra-organizational resources as family or friends [20]. The ability of nurses to mobilize the sources of support of the unit staff is related to their position in the network because nurses who are more centrally located are able to gather both type of support [40]. Relationships with people and coping strategies based on logic were the major indicators of mental ill health for the total sample. In addition, lacking of control on organisational issues, pressures coming from an inadequate home/work interface management and some coping strategies based on logic and use of time predicted a little portion of variance too. According to this, professionals who do not perceive any their effect over the invisible influences within the organization were more likely to have experienced symptoms of mental illness, when they perceived interpersonal stress and did not use coping strategies that allow to face situations without being overwhelmed by emotions. Relationships with people, lacking of control on organisational issues and negative impact of work problems on home life, predicted the physical health of the nursing sample. Nurses who exhibited these patterns tended to reveal symptoms of physical ill health, such as headaches, indigestion, feeling of tiredness, and anxiety. Comparisons between our sample and O.S.I. normative data indicated significant differences in occupational stress variables. Nurses revealed lower satisfaction in each work dimension and somatic symptoms were higher than normative population. It’s important to note that nurses performed significantly higher scores in every perceived sources of stress, except in “Career and achievement”. Professional success is lower if compared with many others professions, and this result suggests that career opportunities are poorer in nursing; therefore, this aspect is not perceived as a source of occupational stress.In summary, the present study revealed that nurses experienced more occupational job dissatisfaction than normative population, and the most important stressors were factors intrinsic to the job, as turnover, besides overload turnover and features of the organizational structure. Moreover, age and gender showed differences in occupational stress levels. Personality variables, such as locus of control, Type A behavior or coping strategies, were critical in our study, but consisted principally in factors of resilience, while organizational and perceived interpersonal pressures were the factors which had greatest influence on prediction of occupational stress and its outcomes. The role of cognition is surely important on how individuals respond to emotional demands, particularly for those professions in which levels of human involvement are high, but not all the effects of work demands are negative or always mediated by attribution, negative emotion or coping strategies [41]. Occupational stress is both an organizational and a personal problem, and nurses’ representations of their organization affect their perception of the climate and relationships. Perceived organizational support is related to nurses’ health and job satisfaction [32], but interventions to improve and increase staff support, which typically operate at individual or group level, may be limited in their effectiveness unless nurses’ perceptions of organizational support are taken into account [42]. Improving quality of the work environment relationships [43], and encompassing and examining a range of identified work and organizational factors would be more effective and profitable interventions in the workplace, to improve employees’ well-being and to address economic and social costs of stress for human resources in the organizations [41, 44]. We believe that such programs could educate nurses to apply constructive strategies of coping routinely rather than using destructive personal ways of dealing with problems. Hospitals in Italy are experiencing massive changes to their organizational structure in an effort to reduce costs and in many cases, organizational changes and reallocating resources means job loss, reduced employee status, and higher levels of workload. Evidences from our study in the province of Mantua can be understood in the light of the current Italian health system that is continuously under scrutiny. It is evident the need to take the suitable measures, in order to assist the health-care professional staffs to turn perceived threats (restructuring, downsizing and turnover) into perceived challenges for managing their occupational stress [19]. Such practices need to be part of a process of interaction between the hospital administration and nurses, and those responsible for the implementation of organizational changes must be sensitive to the larger community effects of these initiatives. Data of our study provides information to the existing body of knowledge about occupational stress problem in Italian hospital nursing system. In addition, the findings suggest which factors are the best predictors for job satisfaction and both physical and mental health. Unfortunately, also this research presents several limitations. First, a survey design was used and, thus, data were collected using only a self-report method; as a result, the researchers had to assume that the respondents were truthful and that they fully understood the questions being asked. Second, often the use of the word stress in the title of a questionnaire presuppose that there is a stress problem in the organization, and respondents could believe that if people were asked to complete a stress questionnaire they should reported more stress than if a more neutral word was used [35]. A revised and improved version of OSI, renamed Pressure Management Indicator (PMI) has been developed; it appears more reliable, comprehensive and shorter than OSI [35], but an Italian translation has not yet been available.The total contribution of the independent variables to the variance of job dissatisfaction, and both mental and physical ill health was not very high, implying that there were other explanatory variables not included in this study; probably, specific stressors related to the clinical work of the nurse and ways of coping, like escape/avoidance, might explain a higher portion of variance in the occupational stress and his outcomes. Finally, the present investigation referred only to a sample of hospital nurses working in a province from the North of Italy, then undergoing to the similar organizational setting. Whether or not the study’s results would generalize to other occupation, to males, and to other geographic areas is presently unknown and requires new research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML