-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(3): 57-63

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120203.01

Factors Affecting Women Participation in Electoral Politics in Africa

Daniel Kasomo

Department of Religion, Theology and Philosophy Maseno University, Kenya

Correspondence to: Daniel Kasomo , Department of Religion, Theology and Philosophy Maseno University, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Women are a major force behind people’s participation in life of society today. Not only do they comprise the majority in terms of population, but they also play a crucial role in society as procreators of posterity as well as producers of goods and services. Although, women have made great strides forward in obtaining a vote and right to be elected to political offices in many countries, they comprise less than 15 per cent of the Members of Parliament, and less than 5 per cent of heads of state worldwide. They hold only a fraction of other leadership positions nationally and internationally. In Kenya, traditional perceptions of women as inferior to men prevail as many people uphold cultural practices which enhance the subordination of women. Consequently, men continue to dominate women in political, economic, social, and religious realms. The latter’s political endeavours, achievements, and roles in society are hardly recognised or acknowledged. This situation has necessitated the clarion call that women should be empowered by giving them due status, rights, and responsibilities to enable them participate actively in decision making at the political level.

Keywords: Politics, Women, Participation, Electoral Process

Article Outline

1. Introduction

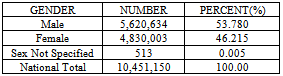

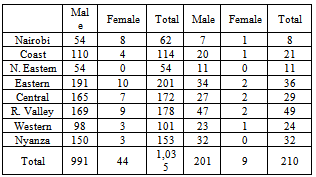

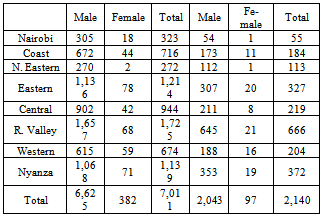

- Over the decades, the issues concerning women have taken on new dimensions and received varied treatment by the United Nations and its specialized agencies. The principle of equality of men and women was recognised in the United Nations Charter (1945), and subsequently in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). In spite of the international declarations affirming the rights and equality between men and women of which Kenya is a signatory, available literature shows that women still constitute a disproportionately small percentage of those participating in political decision-making and leadership. Many global conferences, including the Cairo Conference on Population and Development (1994), the Fourth World Conference on Women (1995), and the World Summit for Social Development (1995) have recognised that, despite the progress made globally in improving status of women, gender disparities still exist, especially in regard to participation in electoral politics. The low participation of women in these positions affects their progress in improving the legal and regulatory framework for promoting gender equality since very few women are influencing the legislative process. The rationale for promoting women’s participation in political dispensation is based on equity, quality and development.Given the nominally higher population of women in Kenya, it is only right for them to equally participate in political decisions on matters affecting them.Several obstacles have been identified that generally prevent women from advancing to political spheres. Adhiambo-Oduol (2003) identifies socio-cultural beliefs, attitudes, biases and stereotypes as major barriers. These emphasize the superiority of men and the inferiority of women. They form the integral part of socialisation process in form of gender education and training that men and women are exposed to from childhood. Another formidable barrier is the institutional framework guiding gender division of labour, recruitment, and vertical mobility. Current estimates show that women are particularly disadvantaged with their labour often under-valued and under-utilized. Women are more likely to be employed than men, yet their average income is lower. Yet another obstacle confronting women is lack of enough participation and empowerment in decisions that affect their lives in political and social processes. Olojede (1990) notes that since men dominate public decision-making processes, it is the male values that are reflected in the decision-making bodies. Kenya’s development record and its demographic composition suggest a need for active involvement of women in key decision-making bodies. There is a clear indication that even though women form the majority voters in Kenya, they are still under-represented in leadership positions. Women’s participation in electoral politics since Kenya’s independence in 1963 has been limited to providing support to male politicians. With the new political dispensation in Kenya, there is a greater need for equal gender participation in acquisition and exercise of political powers. Notably, the repeal of Section 2 (A) of the Kenya Constitution in 1991 to some extent provided this opportunity by allowing room for multi-party democracy and reactivating of the civil society. In this endeavor it was envisaged that a level playing ground and larger political arena would be created for women’s involvement in electoral politics. Yet women are still under-represented in electoral politics. A recent survey in Kenya has revealed that women constitute majority of voters and that their level of participation in electoral politics is minimal. The level of participation of women in electoral politics in Kenya in the last general elections is summarised in the tables below.

|

|

|

2. Statement of the Problem

- In Kenya, women constitute slightly over half of the total population and form a critical portion of enhancing democratization of political system in the country. However, available data indicates that they are inadequately represented in political positions in the government. The possible explanation for this scenario could be that gender issues in electoral politics have not received due attention and redress. This gives their male counterparts a head start. Women are always relegated to the peripheries of political leadership. Burdened with guilt, women are doubly marginalised first because they are women and secondly because they are politicians. Frequently, political information is withheld from women. For instance, in the 2002 general elections many women aspirants were locked out at the nomination stage. In their public and private lives, women have to struggle to articulate their desires and to find their own voices. For a long time, women have been seen as extensions of men; as people who cannot politically stand on their own, but have to be propped by men. While a few researchers have in recent past began to document on women’s participation in management positions in Kenya, such documentation has not focused on factors that affect women’s participation in electoral politics. This purpose of this study is therefore to investigate into the factors that affect women’s participation in electoral politics in Kenya in a bid to come up with possible strategies that can be used to enhance their participation.

3. Objectives of the Study

- The general objective of this study is to investigate into factors that affect women’s participation in electoral politics in Kenya. Specifically, the study aims at:1. Establishing the positions women occupy in political leadership in Kenya.2. Determining the factors that affect women’s participation electoral politics in Kenya.3. Examine the structures and processes which reinforce the subordinate positions of women in political dispensation.4. Suggest possible strategies that can enhance women’s equal access and full participation in political power structures and decision-making.

4. Research Questions

- The proposed study seeks to answer the following questions.1. Why are women still locked out of political parties and denied effective political representation?2. Why do women still appear indifferent to, and ignorant of, political negotiations and procedures? Is it because they have over-emphasized factors which they can do nothing about over those which they can influence?3. Why do some women still believe that politics is not for women? Is it because women are afraid of succeeding in politics and have not adequately applied themselves in this regard?4. Why do some women still prefer incapable male candidates to capable women candidates?5. Why does the society recognise the value that women bring in democratization of the political system as voters and yet do nothing about enhancing their capacity to participate in power structures and decision-making?6. What possible strategies can be used to enhance women’s participation in electoral politics in Kenya?

5. Significance of the Study

- Literature on women in electoral politics in Kenya is scanty. There is no sufficient data on the factors affecting women’s involvement in political dispensation. The significance of this study derives not only from its ability to determine the level of participation of women in electoral politics but also its examination of the factors that affect women’s effective participation. The fact that the study will be a post-election analysis of women’s participation in the last general elections, which ushered in a new political dispensation Kenya, further substantiates its significance. It is hoped that the data gathered from this study would lead to new affirmative action policies that will enhance gender mainstreaming and equal participation in all leadership and development processes. The data will also be resourceful to scholars and policy makers as well as contribute to the inadequate literature on gender participation in electoral politics in Africa in general and Kenya in particular.

6. Conceptual Framework

- This study is guided by the concept that gender is a socially and culturally constructed variable pegged on the role that men and women play in their daily lives. Gender refers to the attributes, opportunities and relationships associated with being a female and male, and the socio-cultural relationships between women and men, girls and boys. These attributes, opportunities and relationships are largely socially constructed and inculcated through socialization processes. Like the concepts of class and/or ethnicity, gender is an analytical tool for a social process. In brief, sex (biological sex) refers to the biological distinction between females and males by nature of birth. Gender (social sex) refers to the socially and culturally learned identity and relations: what is often referred to as woman or man, girl or boy. Unlike sex, the identity of gender does not come from birth. It is socially and culturally constructed and can therefore be deconstructed over time. Gender is not only about roles but also about relations. What people state that women or men are, or shall do, is related to the question of who sets the rules and for what functions. Gender is also about power, privileges, responsibilities, rights and duties. In any working environment or institution, the values, attitudes and beliefs of its personnel regarding gender is transformed and expressed into the institutional and structural system, the culture and the normative framework of the institution.With regard to Kenya, political development process has been perceived from a sexist perspective. As such women have no significant input in the political dispensation. In this regard, the oppression of women and their subordinate positions are thus located in the personal, structural and cultural factors. Pertaining to personal factors, the paucity of women is attributed to psycho-social attributes which entail their personality, attitudes and behavioral skills. Other attributes include low self esteem and self confidence, lack of motivation and ambition to accept challenges, low morale for leadership, being less assertive, less emotionally stable, and lacking ability to handle crises (Nzomo, 1995). Structural factors that negatively impact on women include: male resistance to women in leadership positions, absence of policies and legislation to ensure equal participation of women, discriminatory appointment and promotion practices, and limited opportunities for gender mainstreaming (Smulders, 1998). Cultural factors are linked to stereotypical views about women’s abilities within the cultural context. Also connected to cultural factors is the patriarchal ideology which provides the context upon which women play and accept a subordinate role.The above three factors will guide this study. African male leaders and particularly those involved in politics have taken advantage of these factors to either conceal or legitimize the perpetuation of those oppressive gender relations. While nationalist movements in Kenya had mobilized both men and women in the struggle for independence, through these factors, power was essentially transformed to men who inherited all the colonial administrative apparatus. Hitherto women’s participation in electoral politics in Kenya has been limited to providing support to the male politicians.

7. Literature Review

- The literature on women participation in electoral politics in Kenya is very scanty. However a review of related literature from other parts of the world will suffice. The review will be done under three broad categories. The first category deals with situation analysis of women in political leadership. The second category will examine the structures and processes that enhance the subordinate positions of women in political dispensation. The third category deals with strategies for enhancing women’s participation in political power structures and decision-making.

8. Situation of Analysis

- Level of women employment in the public sector is an indicator of women’s participation in decision-making in a country’s administration. Complement Control Statistics in Kenya as at March 2001 show that women are concentrated in low-paying, low social status jobs in the public service in terms of income and decision making powers. The concentration of women decreases with the increase of the level of the job group. The higher the job group, the fewer the women who occupy it. In that case, only a small percentage of women compared to men are in key positions to make and influence decisions in public service. This study will find out how the level of employment of women in various sectors in Kenya affects their participation in electoral politics.Participation of women in decision making bodies on equal terms with men is guaranteed in Kenya’s constitution. Nevertheless, the absence of women in decision-making position defeats the equality implied in the constitution. Kenya’s women feel disillusioned and cheated by a government that promised them increased participation in decision-making, but failed yet again to appoint equal number of women to ministers, let alone a woman to a vice-president (African Centre for Technology Studies - ACTS, 1994). The bottom line therefore is that the present political dispensation, in spite of popular rhetoric, wants to keep women out of the political arena, as it seems not to be prepared to equally share power with women. What Kenyan government needs are not just a few women who make history, but many women who make policy. Kenya’s political developments record highlights the need for devolution of powers. This is an area where women need to provide leadership and chart a course that can provide space for them as one of the marginalised groups of Kenyans. At independence in 1963, Kenya was a constitutionally devolved state with gender issues well catered for. This status quo was changed by carefully orchestrated Constitutional amendments in the period 1964-1969. Gender issues were thus disregarded. In giving their views to the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC), many women felt that devolution of powers should be revitalized as this would: give them equal parliamentary and local representation; ensure greater women control over resources such as land; ensure a general principle of mixed member proportion system so that at least one third of the total elective posts and public appointments be occupied by women; permit independent candidates in general elections so that women are not dependent on party nomination; ensure fair representation of women in legislative chambers, district and local councils (CKRC, 2002). Clearly, women in Kenya are disempowered and alienated from the government. The 2002 general election results released by the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) showed that more women participated in electoral politics than at any other time since independence in 1963. 97 women candidates were elected as councilors compared to 2043 men, while 9 women were elected to parliament compared to 201 men. 8 women were subsequently nominated to the parliament. While women’s active participation in the democratization process in Kenya may have induced more women than before to stand for the parliamentary and civic elections, the multi-party era has not led to an automatic concern for women’s issues nor to intensifying their participation in electoral politics. Unless their basic needs are met and their development issues addressed, women will not make any significant landmarks (Engendering Political Process Programme, 2003). In Kenya, local authorities are essential extensions of the Central Government administrative set up. Their functions are to provide facilities and services such as education, health, housing, water, sewage disposal, road construction and maintenance. Currently, local authorities are organized into city, municipal, town, urban and county councils (Government of Kenya - GoK, 2001). Those who run the local authorities are elected to posts as councilors and mayors. Despite the fact that women have played significant roles in communities since independence, they have not fared on well in the local authority elections. According to Women’s Bureau/SIDA (2002), very few women have been elected as councilors. Men form the majority of the mayors and chair-persons of the councils. Need arises to find out what has contributed to limited participation of women in politics and decision-making at the local level.

9. Structures that Enhance Subordination of Women in Politics

- The traditional female/male roles are deeply ingrained and glorified in all Kenyan languages, in education, the mass media, and advertising. The society’s perception of women is for the most part negative with the best women as mothers, and their capabilities and capacities going virtually unnoticed (Obura, 1991). Such sex stereotypes and social prejudices are inappropriate in the present society where female/male roles and male-headed families are no longer the norm. According to the United Nations (2000), sex stereotypes are among the most firmly entrenched obstacles to the elimination of discrimination, and are largely responsible for the denigration of the role and potential of women in society. The subordinate position of women in the society seems to legitimize their exclusion from participation in political and decision making processes. Many stories depict women as disloyal, disagreeable, untrustworthy, stupid and even gullible (Kabira and Nzioki, 1995). Even today women continue to be left out of official records and when recognised, they are addressed as those who need welfare assistance rather than actors in the historical process. The heavy under-representation of women in political life and most decision making processes in Kenya needs to be closely investigated. This study will investigate into why Kenyan women are politically dormant yet they constitute an enormous political energy that is under-utilized.Karl (2001) explores some of the factors affecting women’s political participation worldwide. Among the factors she cites include: house-hold status; work related rights (maternity leave, job security, provision of child-care); employment and remuneration; double burden of work; education and literacy; access to financial resources; legal rights; traditions, cultural attitudes and religion; socialization and self-reliance; violence against women; the mass media; health; ability to control fertility. It would be interesting to investigate into how far these factors impact on women in the political realms in Kenya today. Cooper and Davidson (1982) sought to study the problems that women in leadership positions generally face. They found that women face stress from both the work, home and social environments. In addition, women have to acquire male leadership and managerial skills (for example, being aggressive, assertive, confident), as well as multiple demands in running a career and a family. Other sources of stress include difficult working relationships with male bosses and colleagues, sexual harassment, limited opportunities for promotion and career development. This research seeks to find out how far these challenges impact on women politicians in Kenya. The study further envisages to come up with strategies that would help women to cope up with turbulence that they face with regard to participation in electoral politics in Kenya. The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) (2003) notes that gender equity is the process of being fair to women and men. To ensure this fairness, measures must often be available to compensate for historical and political disadvantages that prevent women from otherwise operating on a leveled playing field with men. Equity leads to equality. Gender equality implies that women and men enjoy the same status. Gender equality means that women and men have equal opportunities for realizing their full human rights and potential to contribute to political, economic, social and cultural development, and to benefit from results thereof. Gender equality includes both quantitative and qualitative aspects. The quantitative perspective concerns the physical gender balance in numerical terms. The qualitative perspective focuses on the equal distribution of power for both women and men. How far are the quantitative and qualitative aspects of gender equality in political circles ensured in Kenya?

10. Enhancing Women’s Participation in Political Power Structures and Decision-Making

- A survey carried out among national parliaments in the world by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (1997) revealed that women make up less than 5 per cent of world’s heads of state, heads of major corporations, and top positions in international organizations. Five years down the line, the IPU has established that women are not just behind in political and managerial equity, they are a long way behind. Politics is everyone’s business and affects the lives of each of us. The more women are associated in numbers in political decision making process in governments, the more they can change the modalities and outcomes of policies. Only then will the concept of democracy find concrete and tangible expression. This study will come up with strategies for enhancing women’s participation in political power structures and decision-making in Kenya. Women and men are different in a number of aspects. Making equal use of both sexes encompasses more perspectives, qualities and inputs. Since gender equality is fundamental for equal rights, opportunity, access of power etc., it is of utmost importance to reflect these conditions in a country’s political organization structure. IDEA (2003) maintains that in order to mainstream gender equality in politics in any country, a clear programme needs to be designed, where entry points for follow-up on gender equality perspectives can be identified. A thorough gender analysis of national context must therefore be made to highlight inequalities, and to take action on promotion of gender equality. Clear operational goals should be set for the programme with regard to strengthening gender equality. This study envisages investigating the relevance of such a programme in Kenya.Women’s groups in Kenya have a long history. Through these groups women have helped each other in time of need. Women’s groups are the catalysts for Kenya’s development. There are over 50 women’s NGOs in Kenya (Gok, 2001). They can broadly be categorized as social welfare organizations, professional organizations, political organizations, religious organizations, and co-operatives. Some of these organizations are very small while others have large national membership. While some of these organizations are purely local in character, others have international affiliation on whose charters their activities are based. These organizations can be avenues for promoting women’s participation in political power structures and decision-making. This study envisages to investigate into how far these organizations have enhanced women’s participation in electoral politics in Kenya.

11. Research Methodology

11.1. Research Design

- The study will employ three types of research design, namely: explorative, descriptive, and survey. Explorative design has partly been utilized in the introductory part of the proposal and literature review. The design has also been used to formulate the objectives and research questions. This design will further be used to clarify the phenomena by identifying the factors that affect women’s participation in electoral politics in Kenya. Descriptive design will be used to analyze the data. It will be used to describe the characteristics of women who are currently engaged in politics and those who have failed in political turbulence. Survey design will be used in the research instruments such as questionnaires, interview schedules and focus group discussions (FGDs).

|

12. Area and Scope of Study

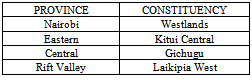

- The study will be conducted in the four provinces and constituencies as shown in table 4 below. It will also focus on political parties, lobby groups and coalitions. These will provide an excellent field laboratory since they engage in issues that affect women in socio-political realms. Based on the 2002 level of women participation in electoral politics results (Table 1 and 2 above) it is appropriate that the following provinces and their respective constituencies be selected for the study:

11.2. Sampling Procedure

- From the 8 provinces in Kenya, 4 provinces have been purposively selected on the basis of level of women participation in electoral politics. On the same basis, one constituency in each province is selected. In each constituency, the study population will consist of people who have been, or are actively engaged in electoral politics either before, during, or after elections. The following categories of samples will be considered for the study:Category One: Consists of political parties, lobby groups and coalitions. A list of registered political parties will be obtained from the registrar of societies. Purposive sampling will be employed to select political parties with higher number of women participants. Offices of these parties will be visited. Offices of the leading women’s political groups such as the Kenya Women’s Political Alliance (KWPA), League of Women Voters, National Women’s Convention (NWC), will be also visited. In this category data will be gathered to establish the efforts made to actively involve women in electoral politics. Category Two: Entails women who have taken part as candidates for both civic and parliamentary seats, and their chief campaigners. The category will yield crucial data on the challenges women face first because of being women and second being politicians.

13. Data Collection Methods

- In field research, the study will triangulate a number of data collection methods: self-administered questionnaires, interviews, and FGDs. The researcher will engage four field assistants, one per every constituency considered. Interviews will be recorded in audio tapes. With regard to library research, relevant libraries and documentation/resource centres will be visited. Internet search will also be done to gather relevant data.

14. Data Analysis

- Data recorded in other languages will be translated into English. Information recorded in audio tapes will be transcribed. Field data will be analyzed and integrated with secondary data, then thematically organized according to the objectives of the study. Through this organization, chapters of the report will be drawn. Qualitative and quantitative methods of data analysis will be applied. Descriptive and analytical methods will be used to present the data in various chapters of the report. In the report, documentary data will be organized and presented in the form of tables and percentages.

15. Conclusions

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to take part in the government of her or his country regardless of sex, race, ethnicity, religion or creed. Since women constitute over 50 per cent of the population in Kenya, their equal right of access to political decision-making positions needs to be emphasized. Achieving the goal of equal participation of women and men in decision-making positions will provide a balance which more accurately reflects the composition of the society, interests and the general good of all citizens. The diversity of perspectives and experiences with regard to gender is highly valued as part of national development. Therefore, where women are under-represented in activities within political leadership, emphasizing a gender equality perspective is necessary.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML