-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(2): 28-37

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120202.05

The Significance of Preschool Teacher’s Personality in Early Childhood Education: Analysis of Eysenck’s and Big Five Dimensions of Personality

Sanja Tatalović Vorkapić

Department of Preschool Education, Faculty of Teacher Education, Rijeka, 51000, Croatia

Correspondence to: Sanja Tatalović Vorkapić , Department of Preschool Education, Faculty of Teacher Education, Rijeka, 51000, Croatia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Considering the significance of the preschool teacher’s influence on early childhood, it is relevant to put in the research focus their personality characteristics. Therefore, the main question of this study was to explore personality traits of preschool teachers. A personality analysis was run and discussed within two personality models: Eysenck’s and Big Five personality model. Subjects were preschool teachers (N=92), all females, with the mean age of 30 years, ranged from 21 to 49 years. Personality traits analyses within both personality models showed higher levels of extraversion, agreeableness, consciousness, openness to experience and social conformity than normative sample. Psychoticism level was similar to the one from normative sample, and neuroticism levels (Eysenck’s and Big5) were lower than in normative sample. The results were discussed in the frame of the significance of preschool teacher personality as a role models and (none)desirable personality traits in the context of early and preschool care and education.

Keywords: Eysenck’s Personality Dimensions, Big Five Model, Preschool Teachers

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- „It is through othersThat we develop into ourselves“(L. S. Vygotsky, 1981, p. 161)Most adults are able to remember their earliest childhood and their “favourite preschool teacher“: the one who made us welcome, who dried our tears, comforted us when we had bruised and taught us our first understanding of right and wrong. Besides, we could clearly recall that we had a strong emotional bond with that significant other (Bauer, 2008), or in what way that exact person influenced on us. Similarly, every preschool teacher has her/his own professional motivation and kind of personality that enable them to pursue the primary goal of satisfying children’s' needs. One of them could be seen in one part of Ana’s interview, who is well-respected, experienced early childhood educator, working more than 30 years with children as Portuguese kindergarten teacher:“…One of the things I treasure is that children feel accepted, as they are more specifically those children who have been emotionally or socially and economically deprived… What I want a child to learn is that she can be herself and should leave the early childhood classroom [experience] with an inner strength. This inner strength is built day after day... In kindergarten, all children should have an opportunity.” (Vasconcelos, 2002, p. 192).The experiences of preschool teachers and children makes us wonder what kind of personality does preschool teacher need to have to make such positive influence on the child? Even more, if we want to describe typical preschool teacher’s personality within the modern personality theories, what that description would be? What kind of personality traits would have a typical preschool teacher, or the most(least) liking one? Unfortunately, there is limited research about what makes a good preschool teacher (Ayers, 1989; Yonemura, 1986). Since the process of early learning and teaching is far more complex, it is crucial to analyse preschool teacher's personality traits, which definitely play a significant role in that same process. The preschool teacher-child interaction and whole climate of kindergarten group directly depend upon preschool teachers’ personality. His/her personality influences on his/her sensitivity to the preschooler’s personality that is in its formative stages. This is very important because pre-schoolers will only learn when they are in a trusting environment (Bauer, 2008). Besides, recent studies have demonstrated that teaching is not merely a cognitive or technical procedure but a complex, personal, social, often elusive, set of embedded processes and practices that concern the whole person (Hamachek, 1999; Oakes & Lipton, 2003; Britzman, 2003; Cochran-Smith, 2005; Olsen, 2008b).Generally, personality could be defined as a cluster of traits that determine individual-specific responses to the environment (Musek, 1999) and make human behaviour and experiencing more consistent (John & Srivastava, 1999). Personality has been conceptualized from a variety of theoretical perspectives (John, Hampson, & Goldberg, 1991; McAdams, 1995). Each of these personality models has made unique contributions to our understanding of individual differences in behaviour and experience (John & Srivastava, 1999), and tried to embrace as wide a range of human behavioural patterns as possible by its limited system of assumptions or constructs (Buško, 1990). Two personality models are dominant and concurrent paradigms in personality research: the Eysencks’ PEN (Eysenck, 1967) and the Big Five model (Goldberg, 1999).

1.1. Eysenck’s personality theory

- Even though Eysenck’s personality theory had its peak dominance in seventies and eighties in previous century, it still has been intriguing in the field of personality psychology. It (Eysenck, 1947, 1967) has its roots in rigorous empirical results from factor analyses of various personality traits’ indicators and measure instruments. Eysenck’s theory is based on the physiological findings from Pavlov’s research of classical conditioning, and on the concepts of excitation-inhibition and arousal hypotheses. According to that, he claimed that personality traits (as measured by questionnaires such as the EPQ) actually reflect individual differences in the ways that peoples’ nervous systems operate. The greatest contribution of Eysenck's theory is in the possibility of detecting genetic factors and of determining the universality and stability of personality dimensions (Milas, 2004). Consequently, Eysenck (1967) has identified three main personality dimensions and the influence of the nervous system and the brain on these dimensions: stability/instability (neuroticism), introversion/extraversion and psychoticism. Emotionally unstable personality is moody, anxious, tense, depressive, restless and touchy; a stable personality is reliable, calm, even-tempered, carefree and has leadership qualities. An introverted personality is quiet, unsociable, passive and careful; an extroverted personality is talkative, lively, active, optimistic, sociable and outgoing. Psychoticism is described by characteristics such as aggressive, more ruthless, egocentric, insensitive, antisocial, impulsive and tough-minded.

1.2. Five Factor model of personality

- It seems that researchers, who tried to solve the problem of lack of paradigm in personality psychology, which consequently resulted with too much personality theories, have succeeded. Therefore, the discovery of five basic dimensions of personality called Big Five (Goldberg, 1999) is considered as the one of the most important events in 20th century in personality psychology (Mlačić, 2002). The Big Five model is substantially descriptive, with the emphasis on the taxonomic aspect (MacDonald, Bore, & Munro, 2008). It is based on Galton's lexical hypothesis (1884) which presumed that the most important individual differences in human transactions would be noted as separate words in some or all world languages (Goldberg, 1982). In other words, it was supposed that psychological and social realities were adequately reflected through the language, and “structure of personality traits is placed in the structure of everyday language” (Kardum & Smojver, 1993, p. 91). According to that theory, personality can be described by means of five factors: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and intellect/openness to experience (Pervin & John, 1997). Individuals scoring high on extraversion have high quantity and intensity of interpersonal interactions, are very active and dominant, have positive emotionality, and are sociable, talkative and affectionate. Opposite to them, persons low on that dimension are described as unsociable, quiet, reserved, unexuberant, balanced, serious, aloof, and task-oriented. Highly agreeable individuals are soft-hearted, of a good nature, trusting, helping, forgiving, open persons, straightforward, honest, whereas those on the opposite pole of the dimension are seen as ruthless, suspicious, cynical, mocking, rude, irritable, vengeful, uncooperative, and manipulative. Furthermore, individuals scoring high on conscientiousness are known as self-disciplined, organized, reliable, assured, punctual, scrupulous, ambitious, committed, persevering, neat, polite and considerate. Opposite to them are persons who are unreliable, lazy, careless, negligent, imprudent, inconsiderate, indifferent, weak-willed, inert, hedonistic, aimless, and with no aspirations. Individuals highly positioned on neuroticism exemplify as unreliable, inadequate, worrying, nervous, irritable, easy jumping, insecure and frequently hypochondriacally. Low positioned individuals are calm, relaxed, hardy, secure, and self-satisfied. Finally, persons scoring high on intellect/openness to experience are described as intelligent, creative, operational, imaginative, adventurous, curious, of broad interests, and non-conventional. On the contrary, those scoring low are not curious, not interested to explore, traditional, down-to-earth, narrow-hearted, limited and inartistic (Pervin & John, 1997).

1.3. Preschool teacher’s personality in the light of Eysenck’s and Big Five dimensions of personality

- A certain number of studies demonstrated that extraversion and emotional stability from Big Five model are congruent to extraversion and neuroticism from the Eysenck’s model (Mlačić & Knezović, 1997). Moreover, agreeableness and consciousness present an opposite end of the psychoticism, and they are moderately to highly correlate with each other (Mlačić i Knezović, 1997). Likewise, if we exclude the intelligence, intellect/openness to experience does not have its synonymous pair in Eysenck’s model. At this moment, Big Five model presents the most integrative frame from research in personality psychology (Mlačić i Knezović, 1997), so this was the main reason to use it in analysing the preschool teacher’s personality. Besides, strong empirical validation and great congruency of Eysenck’s theory with Big Five model present very valid reasons to use this personality model in exploring preschool teacher’s personality.As it was mentioned earlier, there is a big lack of systematic and scientific exploration of preschool teacher’s personality. The majority of studies explored the competencies that future preschool teachers should have (Vujičić, Čepić & Pejić Papak, 2010), what faces or roles could preschool teachers have (Slunjski, 2004, 2008) and what are the significant factors that influence their professional development (Vasconcelos, 2002, Ling, 2003). Within their research, authors used concepts such as reflective practitioner, competencies, eneagramic approach in different faces/roles of preschool teachers, enthusiasm and personal fulfilment by work within the frame of qualitative methodology (mainly interviews with open and non-structured questions). Even though all studies very qualitatively dealt with the question what makes a good kindergarten teacher, none of them explores them in the context of modern personality theories using quantitative methodology approach. Besides, all of them have investigated and discussed about concepts that were determined by personality characteristics of preschool teachers – because the same competency and its same level could be very differently manifested in one introvert or one extravert, or in preschool teacher who was emotional stable or not. In addition, the only one set of similar studies is the one consisted of investigation of similar personality models but in the samples of schoolteachers (Kenney & Kenney, 1982; Keirsey & Bates, 1984; Korthagen, 2004; Emmerich, Rock & Trapani, 2006; Zhang, 2007; Decker & Rimm-Kaufman, 2008). Again, as it would be discussed later, even though both professions work in the learning and teaching setting, they were rather different due to great number of factors. So, any attempt of using the same study conclusions that are valid for school teachers’ personalities could not be valid for preschool teachers’ personalities. Finally, some studies have been focused on certain personality characteristics of preschool teachers outside the specific personality theory frame, such as empathy or imagination. The results showed that children from groups led by more emphatic and more imaginative teachers were more prosocial, while the children from groups led by less emphatic and less imaginative educators were found to be more aggressive (Ivon & Sindik, 2008). In addition, the same study established that children led by more emphatic and imaginative teachers used more imaginative games, particularly the symbolic puppet play, and did practical activities in small groups or pairs. Taken altogether, it is obvious that various personality characteristics are more than significant in the preschool setting. So, they definitely deserve to be objectively and quantitative analysed within previously described personality models.

1.4. The aim of this study

- The goal of the present study was to examine personality structure in preschool teachers within two dominant personality theories: Eysenck’s personality theory and Big Five model of personality. Within Eysenck’s personality theory it was supposed that extraversion would be higher and neuroticism would be lower than in normative sample concerning the preschool teacher’s role in the preschool setting as an talkative and warmth individual with the emphasized emotional stability which is very important in the work with children. Within the Big Five model of personality it is expected that the dimensions of extraversion, agreeableness and openness to experience would be higher and neuroticism would be lower than in normative sample. Again, this hypothesis is made according to preschool teacher’s role in preschool setting where the basic prerequisites of successful work with children and parents are higher levels in: sociability, warm-heartedness and activity; soft-heartedness, honesty and forgiveness; curiosity, creativity and imagination; emotional stability security and relaxation. Finally, it is expected to determine no significant correlations between age and any personality variables, concerning the age level of preschool teachers. Besides, it is expected to determine that preschool teachers with higher working experience would also have a higher level of consciousness, since this personality dimension is frequently closely connected with the growing work experience.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- In this study participated N=92 preschool teachers, all females with the mean age 30.5 years (SD=6.65), ranged from 21 to 49 years. The mean of their working experience was 6 years, ranged from 0 to 30 years of working within preschool care and education. All subjects were enrolled at the Life-long learning course for preschool teachers at the Faculty of Teacher Education. N=67 participants were enrolled at the year 2010 and N=25 were enrolled at the year 2011. The sample was suitable because all students were the preschool teachers with at least some working experience and from different parts of our country.

2.2. Measures

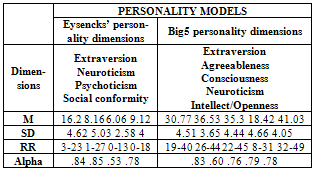

- Eysenck’s Personality Questionnaire – Revised (EPQ-R). To analyse personality structure in preschool teachers, two personality questionnaires have been applied. Eysenck’s Personality Questionnaire – Revised version, EPQ-R (Eysenck, Eysenck & Barrett, 1985), its standardized version (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1994), to be precise, has been used to measure the levels of extraversion, neuroticism, psychoticism and social conformity. This instrument consisted of 106 items: Extraversion subscale = 23 items (item example: “Do you have many friends?”); Psychoticism subscale = 32 items (item example: “Do you enjoy to insult people who you love?”); Neuroticism subscale = 24 items (item example: “Have you often felt guilty?”); and Social conformity subscale = 21 items (item example: “Have you ever damaged or lost others stuff?”) on which participants answered choosing between YES and NO. The level of a certain personality dimension resulted as a sum of answers on relevant EPQ-subscale. Item analysis in this study confirmed earlier satisfactory levels of reliability, as it could be seen in Table 1. Even though the reliability levels of psychoticism and social desirability are something lower than the ones from the normative study, they are still satisfying.

2.3. Procedure

- At the end of their enrolled Life-long course (for the first generation in early spring 2010. and for the second generation in early spring 2011. year) students (N=92) were asked to participate in the study which analyse dominant personality characteristics of preschool teachers. Therefore, those students who accepted to participate filled out two described questionnaires. In addition, they were told that the research was anonymously and collected data privacy was guaranteed. Questionnaires application has been long for about 15 minutes and after that, the students were promised to be informed about the study results. SPSS has been used for performing needed statistical procedures: descriptive and correlation analyses.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Eysenck’s personality dimensions in preschool teachers

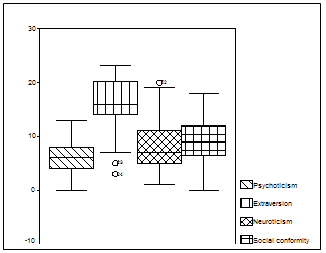

- Conducted statistical analyses showed (Table 1, Figure 1) a rather different averages in all subscale’s results, than we could observe in normative sample (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1994) of the same average age (30 years).

| Figure 1. The distribution of four EPQ/R-subscales results: psychoticism, extraversion, neuroticism and social conformity |

3.2. The Big5 personality traits in preschool teachers

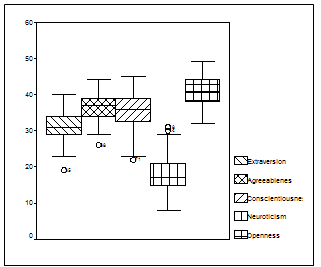

- Further statistical analyses showed (Table 1, Figure 2) again something different averages in all subscale’s results, than we could observe in normative sample (Srivastava et al., 2003) of the same average age (30 years), or in similar studies conducted in our country (Kardum, Gračanin & Hudek-Knežević, 2008). Overall, preschool teachers score higher on all BFI-subscales than normative sample (Mextraversion=26.24; Magreeableness=27.03; Mconscientiousness=32.67; Mopenness=39.40; Srivastava et al., 2003), except on neuroticism subscale (Mneuroticism=25.76), where they scored significantly lower (Table 1, Figure 2).

| Figure 2. The distribution of five Big5-subscales results: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and intellect/openness to experience |

3.2. Correlation Analyses

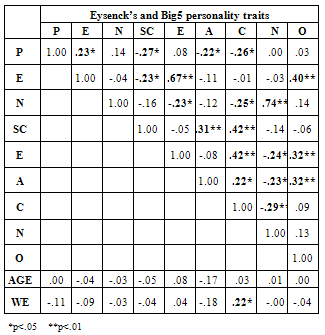

- The results from conducted correlation analysis of different personality variables, age and work experience could be seen in Table 2.

|

4. Conclusions

- Having in minded that: “Real knowledge comes from those in whom it lives. — John Henry Newman“ (Olsen, 2008a, p. 3), it is very important to scientifically focus on personality traits of preschool teachers. All our preschool teachers and schoolteachers that we had in life have been very important to us, and we definitely remember them for better or for worse (Vasconcelos, 2002). Within the picture of our preschool teachers that we remember, their personalities play a crucial role. This study is significant because it brought the most recent data regarding preschool teacher's personality, while there is a lack of similar objective studies. Within two personality models: Eysenck's and Five Factor, the conducted analyses showed that preschool teachers had higher levels of extraversion, agreeableness, consciousness, openness to experience and social conformity than normative sample. Psychoticism level was similar to the one from normative sample, and neuroticism levels, from the perspective of both personality models, were lower than in normative sample. Some different interrelationships between certain personality traits implied at some specificities of personality structure in preschool teachers regarding their professional role as role models and those who had primary aim of identifying and satisfying children’s needs in the preschool setting. Finally, correlations of age or working experience just confirmed prior studies of personality stability within those two personality models and the expected higher agreeableness with the higher working experience. “…That the teaching act becomesThe resonance of all our being”(Sylvia Ashton-Warner, 1963)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to thank all Croatian preschool teachers who have been participated in the study, on their good will, time, effort and great cooperation. In addition, I would like to thank prof. Kardum on his great support and cooperation.

References

| [1] | Ashton-Warner, S. (1963). Teacher. New York: Simon & Shuster/Bantam. |

| [2] | Ayers, W. (1989). The good preschool teacher: Six preschool teachers reflect on their lives. New York: Teachers College Press. |

| [3] | Bauer. S. (2008). What Qualities Should Preschool Teachers Have? Jakarta Post, September. [Online]. Available: http://www.tutortime.co.id/images/download/Teachers+role.pdf. |

| [4] | Benet-Martinez, V. & John, O. P. (1998). Los cincos grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 729-750. |

| [5] | Bonifacio, P. (1991). The psychological effects of police work: A psychodynamic approach. New York: Plenum Press. |

| [6] | Bratko, D. (2002). Kontinuitet i promjene ličnosti od adolescencije do rane odraslosti: Rezultati longitudinalnog istraživanja [Personality continuity and change from adolescence to young adulthood: Longitudinal study. In Croatian.] Društvena istraživanja, 4-5(60-61), 623-640. |

| [7] | Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. |

| [8] | Buss, A. H. & Plomin, R. (1975.). A temperament theory of personality development. Willey, New York. |

| [9] | Buško, V. (1990). Struktura ličnosti i angažiranost sportom. [Personality structure and engagement in sports. In Croatian.] (Graduation paper) Zagreb: Odsjek za psihologiju Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. |

| [10] | Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). The new teacher education: For better or for worse? 2005 presidential address. Educational Researcher, 34(7), 3-17. |

| [11] | Costa, P. T. Jr. & McCrae, R. R. (1997.). Longitudinal stability of adult personality. In: R. Hogan, J. Johnson & S. Brrigs (Eds.), Handbook of Personality Psychology, (pp. 269-290). Academic Press, New York. |

| [12] | Cox, R. H. (2002). Sport psychology: Concepts and application. 5th ed. Missouri, Columbia: McGraw Hill. |

| [13] | Decker, L. E. & Rimm-Kaufman, S. E. (2008). Personality characteristics and teacher beliefs among pre-service teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(2), 45-64. |

| [14] | Emmerich, W., Rock, D. A. & Trapani, C. S. (2006). Personality in relation to occupational outcomes among established teachers. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 501–528. |

| [15] | Eysenck, H. J. (1947). Dimensions of personality. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. |

| [16] | Eysenck, H. J. (1967). Biological basis of personality. Charles C Thomas Publisher, Springfield, Illinois, USA. |

| [17] | Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J. & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the Psychoticism Scale. Personality & Individual Differences, 6(1), 21-29. |

| [18] | Eysenck, H. J. & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1994). Priručnik za Eysenckove skale ličnosti: EPS-odrasli [A manual for eysenck’s personality scales: EPS-adults. In Croatian] Naklada Slap, Jastrebarsko. |

| [19] | Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Rijeka (2010). Early childhood and preschool education – Course program. [Online]. Available: http://www.ufri.uniri.hr/data/RipO-eng.pdf. |

| [20] | Galton, F. (1884). Measurement of character. Fortnightly Review, 36, 179-185. |

| [21] | Goldberg, L. R. (1982). From ace to zombie: Some explorations in the language of personality. In: C. D. Spielberger & J. N. Butcher (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 1, pp. 203-234). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. |

| [22] | Goldberg, L. R. (1999.). A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: I. Mervielde, I. J. Deary, F. De Fruyt & F. Ostendorf (Eds.), Personality Psychology in Europe, 7 (pp. 7-28). Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press. |

| [23] | Hamachek, D. (1999). Effective Teachers: What they do, how they do it, and the importance of self-knowledge. In: R. P. Lipka & T. M. Brinthaupt (Eds.), The role of Self in Teacher Development (pp. 189-224). Albany, N. Y.: State University of New York Press. |

| [24] | Han, D. H., Kim, J. H., Lee, Y. S., Bae, S. J., Bae, S. J., Kim, H. J., Sim, M. Y., Sung, Y. H. & Lyoo, I. K. (2006). Influence of temperament and anxiety on athletic performance. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 5, 381-389. |

| [25] | Ivon, H. & Sindik, J. (2008). Povezanost empatije i mašte odgojitelja s nekim karakteristikama ponašanja i igre predškolskog djeteta [Connection between preschool teachers' empathy and imagination and certain characteristics of preschool child's behavior and play. In Croatian] Magistra Iadertina 3(3), 21-38. |

| [26] | John, O. P., Hampson, S. E. & Goldberg, L. R. (1991). Is there a basic level of personality description? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 60, 348-361. |

| [27] | John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In: O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 114–158). New York, NY: Guilford Press. |

| [28] | John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: L. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed. pp. 102-138). New York: Guildford Press. |

| [29] | Kardum, I. & Smojver, I. (1993). Peterofaktorski model stukture ličnosti: Izbor deskriptora u hrvatskom jeziku [Big Five model of personality: Selection of descriptors in Croatian language. In Croatian]. Godišnjak Zavoda za psihologiju Rijeka, 2, 91-100. |

| [30] | Kardum, I., Hudek-Knežević, J. & Kola, A. (2005). Odnos između osjećaja koherentnosti, dimenzija petofaktorskog modela ličnosti i subjektivnih zdravstvenih ishoda [The relationship between sense of coherence, five-factor personality traits and subjective health outcomes. In Croatian]. Psihologijske teme, 14(2), 79-94. |

| [31] | Kardum, I., Gračanin, A. & Hudek-Knežević, J. (2006). Odnos crta ličnosti i stilova privrženosti s različitim aspektima seksualnosti kod žena i muškaraca [The relationship of personality traits and attachment styles with different aspects of sexuality in woman and man. In Croatian]. Psihologijske teme, 15, 101-128. |

| [32] | Kardum, I., Gračanin, A. & Hudek-Knežević, J. (2008). Dimenzije ličnosti i religioznost kao prediktori socioseksualnosti kod žena i muškaraca [Personality Traits and Religiosity as Predictors of Sociosexuality in Women and Men. In Croatian] Društvena istraživanja, 3(95), 505-528. |

| [33] | Keirsey, D. & Bates, M. (1984). Please understand me: Character & temperament types. California: Prometheas Nemesis. |

| [34] | Kenney, S. E., & Kenney, J. B. (1982). Personality patterns of public school librarians and teachers. Journal of Experimental Education, 50, 152-153. |

| [35] | Korthagen, F. A. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: Towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching & Teacher Education, 20, 77-97. |

| [36] | Leitao de Silva, A. & Queiros, C. (in press). Sensation seeking and burnout in police officers. In: J. Neves & S. P. Gonsalvez (Eds.), Occupational Health psychology: From burnout to well-being (pp. 1-18). Scientific & Academic Publishing, USA. |

| [37] | Ling, L. Y. (2003). What makes a good kindergarten teacher? A pilot interview study in Hong Kong. Early Child Development & Care, 173(1), 19-31. |

| [38] | McAdams, D. P. (1995). The five-facotr model in personality: A critical appraisal. Journal of Personality, 60, 329-361. |

| [39] | MacDonald, C., Bore, M., Munro, D. (2008).Values in action scale and the Big 5: An empirical indication of structure. Journal of Research in Personality 42, 787-799. |

| [40] | McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Jr. (1990.). Personality in adulthood. TheGuilford Press, New York. |

| [41] | Milas, G. (2004). Ličnost i društveni stavovi. [Personality and social attitudes. In Croatian.] Jastrebarsko: Naklada Slap. |

| [42] | Mlačić, B. (2002). Leksički pristup u psihologiji ličnosti: Pregled taksonomija opisivača osobina ličnosti [The lexical approach in personality psychology: A rewiev of personality descriptive taxonomies. In Croatian]. Društvena istraživanja, 4-5 (60-61), 553-576. |

| [43] | Mlačić, B., & Knezović, Z. (1997). Struktura i relacije Big Five markera i Eysenckova upitnika ličnosti. [Structure and relations of Big Five markers and Eysenck’s personality questionnaire. In Croatian.] Društvena istraživanja, 27(1), 1–21. |

| [44] | Musek, J. (1999). Psihološki modeli in teorije osebnosti. [Psychological models and personality theories. In Slovenian.] Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta. |

| [45] | National Pedagogical Standard in Preschool Care and Education in Croatia. Croatian Parlament, Ministry of science, education and sport, Croatia. [Online]. Available: 2008_06_drzavni pedagoski standard predskolskog odgoja i naobrazbe.pdf. |

| [46] | Oakes, J. & Lipton, M. (2003). Teaching to change the world. New York; McGraw-Hill. |

| [47] | Olsen, B. (2008a). Introducing Teacher Identity and This Volume. Teacher Education Quarterly, Summer. |

| [48] | Olsen, B. (2008b). Teaching what they learn, learning what they live: How teachers’ personal histories shape their professional development. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers. |

| [49] | Pervin, A. L., & John, P. O. (1997). Personality: Theory and research. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. |

| [50] | Petrović-Sočo, B., Slunjski, E. & Šagud, M. (2005). A new learning paradigm – A new roles of preschool teachers in the educational process. Zbornik Učiteljske akademije u Zagrebu, 7(2), 329-340. |

| [51] | Slunjski, E. (2004). Devet lica jednog odgajatelja/roditelja [Nine faces of one preschool teacher/parent. In Croatian.] Mali profesor d.o.o. Zagreb. |

| [52] | Slunjski, E. (2008). Dječji vrtić – zajednica koja uči: mjesto dijaloga, suradnje i zajedničkog učenja [Kindergarten – community that learns: the place of dialog, cooperation and collective learning. In Croatian.] Spektar media, Zagreb. |

| [53] | Srivastava, S., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D. & Potter, J. (2003). Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: Set like plaster or persistent change? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 1041–1053. |

| [54] | Srivastava, S., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D. & Potter, J. (2008). Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: Set like plaster or persistant change? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 84, 1041-1053. |

| [55] | Tatalović Vorkapić, S. & Vujičić, L. (in press). Do we need Positive Psychology in Croatian kindergartens? – The implementation possibilities evaluated by preschool teachers. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development. |

| [56] | Trninić, V., Barančić, M. & Nazor, M. (2008). The five-factor model of personality and aggressiveness in prisoners and athletes. Kinesiology 40(2), 170-181. |

| [57] | Tušak, M., Kandare, M., & Bednarik, J. (2005). Is athletic identity an important motivator? International Journal of Sport Psychology, 36(1), 39–49. |

| [58] | Vasconcelos, T. (2002). “I am like this because I just can’t be different…” Personal and professional dimensions of Ana’s teaching: Some implications for teacher education. In: D. Rothenberg (Ed.), Proceedings of the Lilian Katz Symposium (pp. 191-199). Early Childhood & Parenting (ECAP) colaborative University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, USA. |

| [59] | Vujičić, L., Čepić, R. & Pejić Papak, P. (2010). Afirmation of the concept of new professionalism in the education of preschool teachers: Croatian experiences. In: G. L. Chova, M. D. Belenguer & T. I. Candel (Eds.), Proceedings of EDULEARN10 Conference (pp. 242-250). 5th-7th July 2010, Barcelona, Spain. Valencia: IATED. |

| [60] | Vygotsky, L. S. (1981). The genesis of higher mental functions. In: J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in soviet psychology (pp. 144-188). New York: Sharpe. |

| [61] | Yonemura, M. (1986). A teacher at work: Professional development and the early childhood educator. New York: Teachers College Press. |

| [62] | Zhang, L. (2007). Do personality traits make a difference in teaching styles among Chinese high school teachers? Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 669–679. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML