-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(2): 22-27

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120202.04

Parental Involvement in Early Childhood Care Education: a Study

Lokanath Mishra

Associate professor in Education, Vivek college of Education, Bijnor, India

Correspondence to: Lokanath Mishra , Associate professor in Education, Vivek college of Education, Bijnor, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This research aims at providing solutions to the parental involvement in early childhood care education centres in Orissa. It will serve as an eye opener to parents and the society in helping to modify or re-adjust their mode of parental involvement towards achieving a better future for themselves and their children notwithstanding their busy schedules and in some cases, inadequacy of resources. A survey approach was used through self- administered questionnaires, and analysis was done using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test the hypotheses. Based on the findings of this work, parental involvement, that is emotional care and support has a very big influence on early childhood education, particularly the academic performance of the child. More so, it was observed that the extent of parental educational attainment has a significant influence on the age which the child is being sent to school. This implies that the extent or level of the parental educational attainment and exposure determines the age at which the child is being enrolled to school. It was also discovered that, the residential setting of the parents has nothing to do with the educational performance of the child. On the whole, parental involvement is very essential in early childhood education and this helps to broaden the child’s horizon, enhance social relationships, and promote a sense of self-esteem and self-efficacy.

Keywords: Childhood Education, Parental Involvement, Parental Education and Academic Performance

Article Outline

1. Introduction

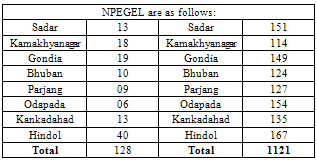

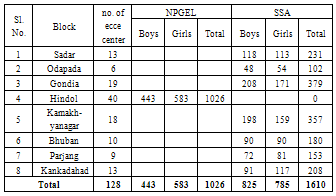

- The first six years of a child's life have been recognized as the most critical ones for optimal development. Since the process of human development is essentially cumulative in nature, investment in programmes for the youngest children in the range of 0-6 years has begun to be accepted as the very foundation for basic education and lifelong learning and development. Over the years, the field of childcare, inspired by research and front-line experiences, has developed into a coherent vision for early childhood care and education.It is now undisputedly acknowledged that the systematic provision of early childhood care and education (ECCE) helps in the development of children in a variety of ways. These include: • Improving group socialization, Inculcation of healthy habits• Stimulation of creative learning processes, and Enhanced scope for overall personality developmentThus, ECCE must be promoted as holistic input for fostering psycho-social, nutritional, health and educational development of young children. For children belonging to underprivileged groups and for first-generation learners in the society, ECCE is essential for countering the physical, intellectual and emotional deprivation of the child. From the perspective of the community, ECCE is a support for the universalisation of elementary education, and also indirectly influences enrolment and retention of girls in primary schools by providing substitute care facilities for younger siblings. ECCE is also envisaged in the role of a support service for working women.The pre-school education component of ECCE has demonstrated a positive impact on retention rates and achievement levels in primary grades. However, it is important to note that attendance in pre-schools does not automatically guarantee better academic achievement. 'Quality' aspects, such as a healthy environment, stimulating activities and encouraging, care-giving teachers, are imperative to ensure all-round development in children.There is sufficient evidence to indicate that early childhood represents the best opportunity for breaking the inter-generational cycle of multiple disadvantages-chronic under-nutrition, poor health, gender discrimination and low socio-economic status. Family and community-based holistic interventions in early childhood to promote and protect good health, nutrition, cognitive and psycho-social development have multiplicative benefits throughout the life cycle.In India, the National Policy on Education (1986), recognizing the crucial importance of early childhood education, recommended strengthening ECCE programmes not only as an essential component of human development but also as a support to universalisation of elementary education and a programme of women's development. Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), the largest government- managed programme at present in the country, is an inter-sect oral programme which seeks to directly reach out to children from vulnerable and remote areas and give them a head-start by providing an integrated programme of health, nutrition and early childhood education. The package of services includes:• Supplementary nutrition• Immunization• Health checkups• Referral services• Non-formal pre-school education• Nutrition and health education for children below six years and pregnant and nursing mothersWhile most of the coverage under ECCE in Orissa in India is carried out through the ICDS scheme, other pre-primary and day-care centers are prevalent with private and not-for-profit initiatives. Also, the Central and state governments have initiated several other schemes mainly to supplement the ICDS provisions in content and coverage. For instance, 'Crèches and Day Care Centres Scheme' was started by the Central Government in 1975 to provide day-care services for children below five years. It caters mainly to children of casual, migrant, agricultural and construction labourers. The programme in the scheme is primarily custodial in nature.Similarly, 'Early Childhood Education Scheme' and Balwadis under the Central Social Welfare Board were introduced as a distinct strategy to improve the rate of enrolment in primary schools and to reduce the dropout rate. Under this scheme, Central assistance is given to voluntary organisations for running pre-school education centres which cater to children in the 3-5 years age group with a view to exposing children from low-income families to early childhood education. They are generally located either at a municipal school, community space, place of worship or the teacher's home and, ideally, comprise 20-25 children with a reasonably qualified teacher from the neighbourhood.In addition to these schemes, there are innumerable private, fee-charging nursery schools which cater to the needs of parents living in urban and semi-urban areas. Efforts have to be made to achieve greater convergence of ECCE programmes implemented by various Government Departments as well as voluntary agencies by involving urban local bodies and gram panchayats.The spread of ECCE facilities, particularly in terms of ICDS centres, and private initiatives, has been phenomenal during the recent years. However, the actual outreach and coverage in respect of early childhood education component, in terms of quality as well as quantity, have been uneven across different parts of the city and the challenge of extending the ECCE facilities to all children is enormous.There is also a strong move towards strengthening the linkage between early childhood education programmes and primary education. Now ECCE centres in Orissa are running under Sarva Sikhya Aviyan(SSA) Programme In this context, This programme is mainly to provide pre- School Education to the children of 3-5 years and to relief the older girls from sibling care. In Dhenkanal District of Orissa 128 ECCE centres are functioning and food is being provided to this ECCE centres through ICDS department. Total 1610 children are enrolled in ECCE centres under SSA and NPEGEL schemes respectively.Block wise ECCE centres under SSA Block wise AWCs are as follows:- Table 1.

No of Children In Ecce Centres of Dhenkanal District of OrissaTable 2.

No of Children In Ecce Centres of Dhenkanal District of OrissaTable 2.  What parents must look for in an ECCE CentreNew research that has focused on the need for integrated interventions addressing child survival, growth and development has noted the impact of health and nutrition status, early stimulation on brain development, importance of early socialization patterns and the quality of the child's immediate environment. These factors critically influence the child's physical, cognitive, emotional and social development in later life. Brain development patterns suggest that learning opportunities in the environment have a dramatic and specific effect, not merely influencing the general direction of development, but also affecting how the brain functions.Addressing 'quality' aspects of ECCE has not yet received the required attention, while the focus continues to remain largely on 'achieving quantitative target figures'. The balance between quality and quantity is more precarious than ever. Indeed, the competing challenges of quantitative outreach vis-à-vis quality dimensions are not easy to overcome but there is urgent and imperative need to appreciate that a balanced approach is crucial.The centers, which are expected at best to provide necessary maturational and experiential readiness to the child, have been turned into regular sessions for training children in the '3Rs' on the plea that admission to primary schools would otherwise be denied. Thus, what should have been a simple pre-preparatory environment for creating interest and readiness for learning becomes a rigorous pressurizing and premature exercise for performance and achievement. Parents need to be aware of the damage created by such pressures on young children.Many issues and concerns confront parents in the selection of an appropriate ECCE centre for their children. At present, in the absence of the system of licensing or recognition of ECCE institutions, the emerging concern is of quality assurance in terms of appropriateness of the learning experiences for children and safety of the environment in which such programmes are conducted. Other closely related issues that emerge in the wake of quality of pre-school centres in Orissa are:• Appropriate qualifications and training of care-givers and educators• Prevention of pressures being imposed on the children for performance and achievement (without consideration for the pace and readiness of individual children)• Channeling undue parental anxiety and demand for formal learning• Neutralizing/balancing the 'over-emphasis' on reading and writing• Checking the over-crowding in the classrooms in gross violation of minimum space requirements per child, etcIt is vital that all the stakeholders (children, parents, neighbourhood and society at large) in the system and advocates for the well-being of children become aware of the need for adherence to the spirit and letter of ECCE rather than be driven by competition and/or commercialization. The issues of quality and accountability for the use of public funds and childcare as a public service need to be at the forefront.Parents and teachers, as stakeholders in the system, need to be aware and conscious of the need to insist on standards of safety at the centers and also for good personnel at these centers. The turnover rate of childcare staff, burnout and emotional distress would be real concerns that parents must be aware of and guard against in the interest of their children.However, it must be noted that at the other end of the continuum of the economic strata, there is a very large group of children who do not even have the luxury of holding a pencil between their fingers and scribbling on paper or even holding a book in their hands. Addressing children at such extremes of the economic divide is not just a concern but also a big challenge.In reviewing the many research findings cited in this document, it is important to remember that they did not, for the most part, emerge from studies conducted with children younger than first graders. Many of these studies are therefore not applicable to these very young children, because the settings and treatments employed in them represent what Katz described above as "formal academic teaching methods that early childhood specialists generally consider developmentally inappropriate for under-six-year-olds." There are, nevertheless, several points of congruence between the two literatures, and these will be noted following a discussion of the research on early childhood education.

What parents must look for in an ECCE CentreNew research that has focused on the need for integrated interventions addressing child survival, growth and development has noted the impact of health and nutrition status, early stimulation on brain development, importance of early socialization patterns and the quality of the child's immediate environment. These factors critically influence the child's physical, cognitive, emotional and social development in later life. Brain development patterns suggest that learning opportunities in the environment have a dramatic and specific effect, not merely influencing the general direction of development, but also affecting how the brain functions.Addressing 'quality' aspects of ECCE has not yet received the required attention, while the focus continues to remain largely on 'achieving quantitative target figures'. The balance between quality and quantity is more precarious than ever. Indeed, the competing challenges of quantitative outreach vis-à-vis quality dimensions are not easy to overcome but there is urgent and imperative need to appreciate that a balanced approach is crucial.The centers, which are expected at best to provide necessary maturational and experiential readiness to the child, have been turned into regular sessions for training children in the '3Rs' on the plea that admission to primary schools would otherwise be denied. Thus, what should have been a simple pre-preparatory environment for creating interest and readiness for learning becomes a rigorous pressurizing and premature exercise for performance and achievement. Parents need to be aware of the damage created by such pressures on young children.Many issues and concerns confront parents in the selection of an appropriate ECCE centre for their children. At present, in the absence of the system of licensing or recognition of ECCE institutions, the emerging concern is of quality assurance in terms of appropriateness of the learning experiences for children and safety of the environment in which such programmes are conducted. Other closely related issues that emerge in the wake of quality of pre-school centres in Orissa are:• Appropriate qualifications and training of care-givers and educators• Prevention of pressures being imposed on the children for performance and achievement (without consideration for the pace and readiness of individual children)• Channeling undue parental anxiety and demand for formal learning• Neutralizing/balancing the 'over-emphasis' on reading and writing• Checking the over-crowding in the classrooms in gross violation of minimum space requirements per child, etcIt is vital that all the stakeholders (children, parents, neighbourhood and society at large) in the system and advocates for the well-being of children become aware of the need for adherence to the spirit and letter of ECCE rather than be driven by competition and/or commercialization. The issues of quality and accountability for the use of public funds and childcare as a public service need to be at the forefront.Parents and teachers, as stakeholders in the system, need to be aware and conscious of the need to insist on standards of safety at the centers and also for good personnel at these centers. The turnover rate of childcare staff, burnout and emotional distress would be real concerns that parents must be aware of and guard against in the interest of their children.However, it must be noted that at the other end of the continuum of the economic strata, there is a very large group of children who do not even have the luxury of holding a pencil between their fingers and scribbling on paper or even holding a book in their hands. Addressing children at such extremes of the economic divide is not just a concern but also a big challenge.In reviewing the many research findings cited in this document, it is important to remember that they did not, for the most part, emerge from studies conducted with children younger than first graders. Many of these studies are therefore not applicable to these very young children, because the settings and treatments employed in them represent what Katz described above as "formal academic teaching methods that early childhood specialists generally consider developmentally inappropriate for under-six-year-olds." There are, nevertheless, several points of congruence between the two literatures, and these will be noted following a discussion of the research on early childhood education.2. Review of Related Studies

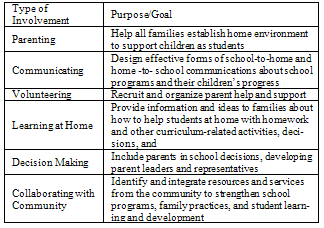

- With the understanding that parent involvement is highly individualized, a broad approach to defining parent involvement is more likely to encompass the full extent of beliefs and expectations presently held by families and providers. To that end, Epstein (2001) suggests that the relationships and interactions among family members, educators, community, and students are similar to partnerships. Dunst (1990) presents a family-centered approach, one where a child’s growth and development is nurtured by the overlapping supports of parents, family, community, and child learning opportunities, as most effective for successful outcomes. Both Epstein and Dunst present the partnerships between families and providers as an opportunity for shared responsibility for facilitating the growth and development of children.Following a comprehensive approach of involvement for family and professional partnerships, Epstein (2001) describes six types of involvement including parenting, communication, volunteering, learning at home, and decision making, and collaborating with the community. Each type of involvement comprises various components (see Table 1). Families and educators can work together to develop goals and establish the best possible practices that are meaningful and appropriate for both parties.

|

2.1. General Objective

- The broad objective of this study is to critically examine the role, effectiveness and impact of parents in early childhood care education in Dhenkanal district of Orissa The specific objectives include the following:• To examine the impact of parents in early childhood years.• To investigate if the socio-demographic characteristics of the parents have an impact on early childhood education.• To examine the factors affecting parental involvement in early child hood education.• To recommend measures to increase the rate and involvement of parents in early childhood education in the study area and also in Orissa

2.2. Research Question/Hypothesis to Be Tested

- • Whether the higher the level of parental involvement in early childhood care education, influenced the educational performance of the child.?• Are the socio-economic characteristics have an impact on early childhood care education?• Whether the more conducive of the learning environment of the child is higher the educational performance.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling Procedure

- A simple random technique was be adopted in the selection of the ECCE centres from 8 blocks of Dhenkanal district.200 respondent (parents)were selected from 50 ECCE Centres (4 from each) taking in to consideration ,no education level, to primary education level, to secondary education level, and tertiary/post-secondary education level from Dhenkanal district of Orissa . 50 ECCE instructor are also selected for collecting the data .The questionnaires were distributed in ECCE centres, through the instructor

3.2. Method of Data Collection

- Since the population was parents of ECCE Centres more so, the respondents are majorly parents and most of them are literate, therefore, the questionnaire was designed in such a way that the respondent will be able to fill-in the answers themselves without having any problem on either of the questions , that is, open and close-ended questions.

3.3. Data Processing

- After returning from the field work, information supplied in the questionnaire was edited to check for inconsistencies and inadequacies. Thereafter, the response were categorized and re-coded where the questions are open-ended type. The coding was used in preparing the frequency tables and cross tabulations. The tables’ cross-tabulations were then prepared for analytical purposes.

4. Data Presentation and Analysis

- Research question I: The higher the level of parental involvement in early childhood education, the higher the educational performance of the child.a. Predictors: (Constant), Do you examine your child's/ward's notes, assignments and class-works?b. Dependent Variable: How can you rate his/her performance? P<0.000(0.000<0.05) R0: There is no significant relationship between parental involvement in early childhood education and the educational performance of the child.R1: There exists a significant relationship between parental involvement in early childhood education and the educational performance of the child.CONCLUSION: Since P value is less than 0.05 .i.e. (0.000<0.05) therefore, we can reject the Null hypothesis (R0) and accept Alternative hypothesis (R1), meaning that there is a significant relationship between parental involvement in early childhood education and the educational performance of the child. From the analysis it is vividly obvious that children are most likely to perform better in their early childhood education with adequate participation of parents.Research question 2: The socio-economic characteristics have an impact on early childhood education.Multiple R 0.351R square 0.123Adjusted R square 0.177Standard Error 20.05493a. Predictors: (Constant), Educational Attainment of the respondentsb. Dependent Variable: At what age did you send your child/ward to ECCE centre P<0.000(0.000<0.05)R0: The socio-economic characteristics do not have an impact on early childhood education. R1: The socio- economic characteristics do have an impact on early childhood education.Since P value is less than 0.05 .i.e. (0.000<0.05) therefore, we can reject the Null hypothesis (R0) and accept Alternative hypothesis (R1), meaning that the socio-economic characteristics do have an impact on early childhood education. The parental educational exposure is very crucial. Some parents just don’t buy the idea of letting their kids experience early childhood education. More so, some parents who are illiterate do engage in practices like; if the child’s hand does not touch the other side of his/her ears then he/she can’t start school. These are kind of old beliefs that should be discarded. So therefore, the parental educational exposure has a very huge impact on the early childhood education.Research question 3 The more conducive the learning environment of the child the higher the educational performance.Multiple R 0.007R square 0.000Adjusted R square -0.006Standard Error 1.12814a. Predictors: (Constant), the residential setting of the respondentsb. Dependent Variable: How can you rate his/her performance?P>0.934(0.934>0.05)R0: There is no significant relationship between the learning environment of the child and the child’s educational performance.R1: There is a significant relationship between the learning environment of the child and the child’s educational performance.

5. Conclusions

- Since P value is greater than 0.05.i.e. (0.934>0.05) therefore, we can accept the Null hypothesis (R0) and reject Alternative hypothesis (R1), concluding that there is no significant relationship between the learning environment of the child and the child’s educational performance. This means that for the fact that a child schools in the rural area doesn’t mean his/her educational performance would be poor, and on the other hand, the fact that a child schools in the urban area doesn’t mean his/her educational performance would be good.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML