-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2012; 2(2): 1-9

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120202.01

Workplace Relationships, Stress, Depression and Anxiety in a Malaysian Sample

Siamak Khodarahimi 1, Intan H. M. Hashim 2, Norzarina Mohd-Zaharim 2

1Department of Psychology, Eghlid Branch, Islamic Azad University, Eghlid, Iran

2Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Siamak Khodarahimi , Department of Psychology, Eghlid Branch, Islamic Azad University, Eghlid, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this research was to develop the Work Relationships Scale (WRS) and examine its relationships with stress, depression and anxiety in workplace, and also to investigate the roles of demographical factors in these constructs. Participants were 199 employees from different workplaces in Penang, Malaysia. A demographic questionnaire and five self rating inventories were used in this study. Findings indicated that WRS is a multidimensional construct with four factors: Critical and procrustean, satisfactory, supportive and sympathic, and disciplinary. First factor was positive correlated with interpersonal sensitivity, demands and control subscales of work stress, depression and anxiety. Second factor was negative correlated with depression, work stress and its support subscale. Third factor was negative correlated with total work stress. Fourth factor was positive correlated with interpersonal sensitivity, work stress and its demands and control subscales. Results supported the effects of gender, marital status, level of education, and type and classification of job on the work relationships. The WRS and its satisfactory and disciplinary subscales altogether explained 30, 3 and 6 percents of work stress, depression, and anxiety variations respectively.

Keywords: Work Relationshp Scale, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Stress, Depression, Anxiety

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Relationships will occur at multiple levels, they are built and broken in various situations but they might bring out many impacts on human behaviors. The phenomenological nature of mental perceptions from relationships in different situations is influenced by everything that has passed through an individual's mind. Desirable and good relationships are essential for physical health, buffering of psychosocial stress and psychological adjustment (1). But negative relationships like disgust related to the higher inter-group interactions, prejudice and rejection of out-groups (2,3). Research suggested that relationships influence emotions and autonomy in adults. Others assumed that relationships are products of social networks and they play positive roles for social support (4,5). However, relationships in different social networks might result in many outcomes since people will attach different meanings to their relationships and their understanding of them (6). Bowlby speculated that infantile relationships with early caregivers are internalized by the child and then they form the prototype for all relationships in adulthood (7). Attach ment theories suggest that individual’ relationships to his/her family, friendship, and work in reality reflect the inherent traits which present in the different attachment styles. Similarly, Bartholomew and Horowitz were described a four category model of attachment in relationships which called the secure, anxious-ambivalent, and avoidant categories of adult attachment (8). Walster, Walster and Berscheid were proposed that the effects of relationships like satisfaction and involvement based upon personal evaluations of how just or fair the distribution of costs and benefits are for each partner (9). Altogether, investigations explained the functions of relationships with respect to the individual perception and perceived outcomes, and it seeming that uncertainty decline in social settings is beneficial for the effective relationships. It would expect that decrease of uncertainty and ambiguities in relationships could reduce high rates of stress and negative emotions. Thereby, relationships considered as a form of benefit and value. Therefore, the quality of relationships influences by networks, norms, social trust, and resources in different social organizations (10-13). In addition, the nature of relationships created by two possible natural and intentional processes. The natural creation of relationships occurs due to the social interaction among individuals who enter or leave the social networks. But intentional proposes imply that individuals exhibit strategic behaviour by seeking outside relationships and social networks to create social capital for their own benefit (10). Coleman was suggested that successful relationships are based on trust, expectation, and reciprocal obligation (10). Furman and Buhrmester were indicated a dichotomy in the nature of relationships that include both positive and negative poles such as affection or conflict, and supportive or negative interactions (14). Alternatively, relationships might influences by the cultural differences. In individualistic societies, people interested to independence, personal goals, and emotional distance from others, equality in personal relationships and superiority in a hierarchical environment, and an individualist's behaviors (15, 16). In a collectivistic culture, people often perceive themselves as a part of the larger whole, esteem interdependence in social relationships, strive for harmony, and value the feelings of others and this perspective can promote a strong interdependent self-construal and a concern with others' emotions (15-17). The Eastern cultures commonly tend to emphasize the complex and interconnected nature of relationships between people at multiple levels and maintain of harmony, and they often apply a dialectical approach this field (18-20). Research indicated the aforesaid differences in Easterners and Westerners often originate in their child- rearing practices (21). However, there is a lack of evidence in workplace relationships and their possible roles in stress and emotional problems.

1.1. Relationships, Stress and Emotional Problems in Workplace

- Adults spend much of their time with others in workplaces and often they experience different relationships in these places, and they might benefit from them or not. Research in workplace relationships in a new field and there is a void of sophisticated theory and literature. Relationships influences by social associations, connections and affiliations, goals, social settings, policies and environment between people who work in these situations, and in return relationships play multiple roles in workplace. Vajda noted that the overlooking of workplace relationships is a major risk in organisational management (22). Since professional success in work- place depends as much on the quality of these relationships. Love argued that winner workplaces will to promote and to develop the good working relationships (23). These relationships often satisfying and they would encourage employee for their creative, whole selves; and openly discussion of employee feelings to each other with honesty and compassion. In contrast, the negative workplace relationships among colleagues might result into many adverse outcomes. Therefore, it assumed that work relationships influences both stress and emotional problems. On the workplace stress, investigations often were regarded the stress as an aversive characteristic of the working environment but there isn’t explicit evidence in regard to relationships and stress interrelatedness. Lazarus was proposed a model of perceived stress in which a person’s perceptions play a critical role in objectively stressful events (24). Karasek was first pioneer who explored the role of workplace relationships in job stress (25). Everly defined the occupational stress as a physiological response that links any given stressor to its target organ causing arousal, and this effect is plausible for work relationships (26). The job stress was considered as a major obstacle in human resources departments throughout all of workplaces and in particular of the human service industry. Research indicated that work stress related to anxiety, depression and negative affectivity (3, 27-31). But in emotional problems area, research indicated that negative relationships are important predictors of depression and anxiety in general (32-34). This notion might be explained as interactions between people and their relationships rather than simply an individual's response to a particular stimulus in a given situation. Since emotional problems are something that emerges through the medium of interaction in the socio-cultural contexts, and initially relationships are the main cause of emotions, and then emotions could lead people to engage in certain kinds of social encounters or withdraw from some relationships. Many emotions have various relational personal meanings, and the expressions of their meanings in different emotional interactions are essential on the nature of the emotional problems in situations.

1.2. Present Study

- Based on aforesaid literature in social networks, attachment and cultural perspectives in relationships; the work relationships seems a substantially new field in psychological research across organizations. Available evidence in this area often focused on a few forms of relationships within the workplace such as rejection sensitivity and attachment styles. Overall, autonomous individuals’ relationships characterized with goal striving, individual standards, independence, and self-directedness but they less equipped and knowledgeable with interpersonal issues (35, 36). Otherwise, people with sociotropy would like to put a high energy on their socially appropriate and prosocial competence. Investigations suggested a possible overlap between in these two dimensions, and presumed that individuals differ in relation to social relations and social knowledge (36, 37). Therefore, this study speculates the significance of relationships in the workplace is a phenomenological issue and it influences the occurrence of stress, depression and anxiety in the workplace. Thus, this investigation could bring up some valuable insights for invention of the effective policies in the workplaces. Overall, the present study suggested possible significant linkages between aforesaid constructs; and it is predicted that they might influence by demographical and organizational factors such as gender, marital status, religion, ethnicity, and level of education, and job type and classification. The first hypothesis of the present study is that workplace relationships have a multifaceted nature. The second hypothesis of this study is that the work relationships, interpersonal sensitivity, stress, depression and anxiety in workplace have significant correlations among a Malaysian sample. The third hypothesis of this study is that gender, marital status, religion, ethnicity, level of education, and types of jobs and workplaces would play significant roles on the work relationships, stress and emotional problems in the workplace. The fourth hypothesis of this study is that the work relationships can predict stress, depression and anxiety in the present sample.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- Participants were 199 working individuals (male n = 101 and female n = 98) from different companies and organisations in Malaysia. They represent various job categories and workplaces in Malaysia. The means (and standard deviations) of age for males and females were 30.71(8.25) and 29.24 (5.65) respectively. Participants were recruited from around campus of a public university in Malaysia. They were the part-time undergraduate students currently doing a long-distance degree program with the university. In the program, part-time students are required to spend two weeks on campus per year. This study was conducted during this academic activity. Participants received minimal honorarium for their participation in the study. After informed consent was obtained, participants completed a demographic questionnaire and five inventories.

2.2. Instruments

- The demographic questionnaire included age, gender, religion, ethnicity, level of education, marital status, order of birth, number of siblings, name of workplace, type of employment, work experience, job title and category. The five inventories used were: (1) the Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale (ISS), (2) the Work Relationships Scale (WRS), (3) the Workplace Stress Scale (WSS), (4) the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and (5) the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale (ISS). The ISS is an 18 items scale and for each item the participant has to reply with a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Sato (35) conceptualized that interpersonal sensitivity is a dispositional fear of causing harm to others and in turn being rejected or criticized. Sato identified two dimensions of sociotropy, and dependence and interpersonal sensitivity. The two dimensions are distinguished by situational factors. Dependency emerges when one is alone, whereas interpersonal sensitivity concerns represent anxiety in the presence of others. The construct validity of Sato’s interpersonal sensitivity affirmed in previous literature by using Sociotropy-Autonomy Scale (38) and the Personal Style Inventory (39). The ISS internal reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was .81 in this study.Work Relationships Scale (WRS). The WRS is a 15-item scale that invented by authors in this study and measure aspects of workplace relationships. This scale measures the nature, content and quality of relationships from a phenomenological perspective in the workplace. Initial items selected based on relationships perspectives and their implications for relationships in workplace. Participants reply to all items using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The WRS concurrent validity measured by Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale (35), and Workplace Stress Scale (40); and it showed .27 and .40 correlations to them respectively. The internal reliability using Cronbach’s alpha were .81, .82, .86, .85 and .83 for all factors and the total scale in this study.Workplace Stress Scale (WSS). The WSS is a short version of Karasek’s 49-items questionnaire (40). This scale based on Karasek’s conceptual model that involves aspects of stress in the workplace. The WSS include three factors: demands (5items, Do you have to work very fast?), control (6 items, Do you have the possibility of learning new things through your work?), and support (5 items, There is a calm and pleasant atmosphere where I work). Participants reply to demand and control items using a scale ranging from 1 (Often) to 4 (Never/almost never). Participants reply to all items using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Reliability by Cronbach’s alpha for all domains ranged from .63 to .86 (De Mello Alves et al, 2004). The WSS internal reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was .82 in this study.The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D includes 20 items that reflecting major dimensions of depression: depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbance (41). It is suggested that this scale be used only as an indicator of symptoms relating to depression rather than as a means to clinically diagnose depression. The CES-D has been used extensively for research purposes to investigate depression among the non-clinical population (42) (Radloff, 1977). For each item the participant has to reply with a Likert scale from 1 (Rarely or none of the time to 4 (Most or all of the time). Its concurrent validity by clinical and self-report criteria, as well as substantial evidence of construct validity has been demonstrated (43-45). The CES-D internal consistency has been reported with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .85 to 90 across studies (41). The CES-D internal reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was 83 in this study.Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). The BAI is a 21-item self- report instrument that assesses the overall anxiety (46). Respondents are asked to rate the severity of each symptom using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (Not at all bothered) to 3 (Severely bothered). The internal consistency of the BAI appears to be quite high with alphas ranging from .90 to .94 in both clinical and nonclinical samples (47, 48). Convergent validity of the BAI has also been established community samples (49, 50). The CES-D internal reliability using Cron- bach’s alpha was .94 in this study.

3. Results

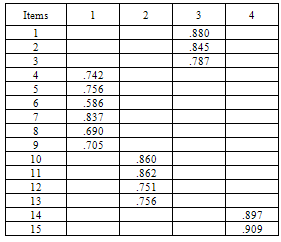

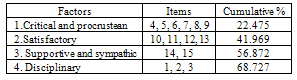

- Initial analysis of data included a factor analysis that was conducted to evaluate possible multidimensional nature of Work Relationships Scale and its construct validity in this sample. Principal factor analysis with varimax rotation was used to determine construct validity, considering Eignvalues higher than 1. Factor analysis specification was satisfactory (KMO = .769, Bartlett's Test of Sphericity = 1.352, df = 105, p = .0001, Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings = 68.72). Table 1 shows the significant rotated correlation higher than .30 for 36 items in 7 iterations.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

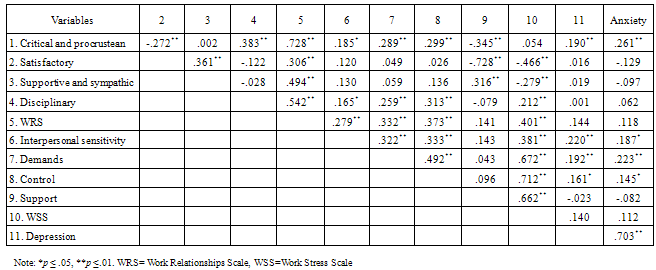

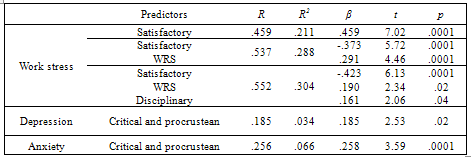

- The results from this study in the first hypothesis demonstrated that work relationship scale is a multidimensional construct with four factors including: Critical and procrustean, satisfactory, supportive and sympathic, and disciplinary. Although this is an exploratory finding and there was no previous evidence due to work relationships multifaceted nature, but present findings were in line with the phenomenological nature toward the relationships. This finding is in agreement to the multifaceted nature of interpersonal relationships in the outwork settings and others social networks like family and friendship (4,5,7-10,14). Thus, workplace relationships include two positive and negative sides and it might explain by child rearing, attachment, cultural values, socialisation and acculturations mechanisms within organisations and their surrounded cultures (7,8,10-13,18,20). The results from this study in second hypothesis indicated that critical and procrustean factor was positive correlated with interpersonal sensitivity, demands and control subscales of stress, depression and anxiety. Satisfactory factor was negative correlated with depression, work stress and its support subscale. Supportive and sympathic negative was correlated with total work stress. Disciplinary factor was positive correlated with interpersonal sensitivity, work stress and its demands and control subscales. The WRS was positive correlated with interpersonal sensitivity, work stress and its demand and control subscales. These findings indicate the multiple functions of work relationships in psychological well being and its possible roles in emotional problems that supported implicitly in previous studies (22,23,32). It seems that work relationships influences the perception of stress, anxiety and depression in workplace by alteration of the individual’s appraisal framework of threatening events, and the increase of his/her interpersonal sensitivity within the Rejection Sensitivity Model (24,25,33,34). Additionally, significant relative associations between work relationships, stress, anxiety and depression can be explained with respect to Mandler and Hallam perspectives(51,52). Mandler highlights a process whereby ongoing cognitive activity is interrupted in anxiety and distress situations. Therefore, critical and procrustean and disciplinary relationships can produces a diffuse autonomic discharge and the detailed appraisal of the source of interruption, and then resulting to the emotional problems such as stress, depression and anxiety. In personal construct theory, Hallam argued anxiety is basically a metaphor based on a construing of certain combinations of the events by an individual that may be including a patient's beliefs (52,53). Based to this theory, it suggests that both work stress and emotional problems are relational entities and they originated in dysfunctional relationships at workplace. The results from this study in third hypothesis indicated that males had higher scores in critical and procrustean and disciplinary factors and females had higher score in supportive and sympathic factor. Females had higher scores in total work stress and its support factor. This findings shows gender differences in interpersonal relationships and stress constructs and it highlights the engendered sex-linked roles in present sample that is often masculine and it is oriented toward the processing of male stereotypes (54,55). As Ticehurst noted this finding highlights necessity of the organizational strategy changing toward the capacity of females and more focus on their demands against women inequality in the work conditions (56). Present findings indicated that singles had higher score in disciplinary relationships, depression, and anxiety but married individuals had higher score in work stress demands. These differences can show the importance of marriage and its psychological advantages for social support, buffering against stress, and its role for the development of a clear definition of the individual's self and worth (57-59). Additionally, there were significant religion differences and the Christians had a higher work stress-control and total work stress than individuals with Hindu, Buddha, and Islam religions. This is incongruent to previous literature in religion and stress perception. For example, King and Schafer suggested that religious experience ameliorate the impact of life's frustrations and difficulties in the Christians, and then they explained the results in terms of attribution and social support theories (60). It suggests this finding related to the societal backgrounds, procedures and practices of different religions in Malaysia. Moreover, present study revealed the effects of education status in relationships and stress in workplace. Individuals with diploma and undergraduate education had significant lower disciplinary relationships than other group, and individuals with primary school education had significant higher job demands, control and total work stress than other groups. This is an exploratory point for relationships but it is in line with a recent investigation due to the role of education for perceived stress reactivity in the workplace (61). Additionally, non professional skilled individuals had significant lower critical procrustean, satisfactory, supportive and sympathic, and the WRS than professional and semi- professional individuals, and professional individuals had significant lower disciplinary relationships than non professional skilled and semi professional individuals. Although there isn’t related literature in this area but it would expect that higher education and professional training result to the lower work stress and maladaptive behaviors because attainment to them can enhance personal knowledge, social resources and professional skills. This is consistent to the finding in this study that shows the public and general services and others workplaces had significantly higher disciplinary relationships and the WRS than education and learning, sales/marketing, administration/human resources, healthcare and manufacturing workplaces. Altogether it seems that gender, religion, marital status, level of education, type of job and the classification of the workplace will produce an organisational culture with specific workplace relationships that is different to each other. Therefore, these differences indicate the nature, meaning, and significance of workplace relationships and their consequences for employee perception of stress and emotional problems. Finally, the results from the multiple regressions for the fourth hypothesis showed that WRS and its satisfactory and disciplinary subscales altogether explained 30, 3 and 6 percents of work stress, depression and anxiety variations respectively. Here, the WRS and its disciplinary subscale had positive relationships with work stress, and it’s critical and procrustean factor has positive relationships with depression and anxiety. When this result will combined to the positive (i.e. satisfactory and supportive-sympathic) and negative (i.e. ccritical and procrustean and disciplinary) subscales of work relationships then its nature would be highly similar to the autonomy and sociotropic dimensions of people relationships in general settings and their effects in emotional problems like depression (35-37). Therefore, it speculated that work relationships included two distinct positive and negative factors and each of them has specific influences on emotional problems and stress in workplace. In line with McCann and Sato conceptualizations the present four factors could differentiate employee differences based on their social relations and social knowledge in workplace.

5. Conclusions

- In sum, the current research adds to the psychology literature because it explored work relationships multifaceted nature and its relationships with stress, depression and anxiety in workplace, and the effects of gender, marital status, level of education, type of job and the classification of the workplace in work relationships in a Malaysian sample. However, present study limited because only relied on a survey data in the Penang, Malaysia. This conceptualization has to be testing nationally within in field and experimental approaches in future studies. Further research may apply experimental and cross cultural designs for this purpose, and to examine these constructs across different cultural samples, and also explore the effects of work relationships in the organisational culture, burnout syndrome, mental health, leadership styles, and the entrepreneurship.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This work was supported by Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) in the Post Doctorate Fellowship of Psychology (SPD050/09) which was held by Dr. Siamak khodarahimi, Clinical Psychologist PhD.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML