Daniel Kasomo

Department of Religion Theology and Philosophy Maseno University Kenya

Correspondence to: Daniel Kasomo, Department of Religion Theology and Philosophy Maseno University Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

This study attempted to find out the factors militating against the education of girls in Lower Eastern Province, Kenya. There is ample evidence in Eastern province that girls have lower educational and occupational aspirations compared to their male counterparts. The main purpose of the research was to establish the magnitude of the effects of the factors that are known to militate against the education of girls. The investigation employed both qualitative and quantitative methods of research. A Survey design was used in the research. The study employed open and closed ended questionnaires administered to all the participants. The results derived from the research were analysed using descriptive statistics. The open responses were subjected to content analysis. The factors investigated comprised: Prevalence of pregnancies, drug addition, Lack of school fees, lack of parental guidance and counselling, lack of interest in school work, Intimate boy/girls relationships, forced early marriages, cultural beliefs regarding education of girls as that of boys, too much pocket money from parents, discouragement from teachers, and Fear of being in the same schools with boys. The significant results of this research have shown that girls have low educational and occupational aspirations and that the greatest hindrance to their educational advancement is alleged to be pregnancy, followed by peer pressure, lack of school fees, lack of parental guidance and counselling, drug addiction and intimate boys/girls relationships. The study recommends that there is need to carry out awareness campaigns to sensitise all stakeholders on the importance of education, especially of the girl child. It is important to create well-maintained single gender boarding schools. Girls should be targeted in terms of bursary and sponsorship.

Keywords:

Counseling, Factors, Education, Girls

Cite this paper: Daniel Kasomo, Causes Touching the Edification of Girls: A Case Study of Eastern Province, Kenya, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 15-21. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120201.03.

1. Introduction

It has been acknowledged that female education is one of the most important forces of development. King (1991) observes that an educated mother raises a smaller, healthier and better-educated family, and is herself more productive at home and at the work place. The researcher noted that there is a correlation between the narrowness of the gap of female education in countries worldwide and the level of development in such countries.However, more boys than girls, particularly in less industrialised countries of Africa, Kenya included, continue to go to school and work their way up the educational ladder (Mueller, 1990). Female enrolment has been lower than that of males at all levels of education in Kenya and especially at secondary and University levels. For instance, in 1998 girls at pre-primary level constituted 48.5%, primary 49.4% and at public secondary schools 30.5% (Republic of Kenya).These overall enrolment figures seem to mask regional disparities. According to (Republic of Kenya, 1988) Ministry of Education statistics in 1996 girls in Northern Eastern Province constituted 52.2%, Nairobi 40.1%, Nyanza 42.4%, Western 44.%. Only three provinces in the republic had enrolment of girls of 48% and above namely; Rift Valley 48%, Eastern 48.5%, and Central 51.2%. This state of affairs is explained by the higher rate of dropout for girls resulting from Socio-cultural factors that underplay the importance of educating girls, Biological factors that makes girls vulnerable to unplanned motherhood, and economic constraints. Some respondents indicated that families who cannot afford to send both sons and daughters to school reckon that financial returns on expenditure for girls are less those than of boys. The arguments is that girls are transient since they will eventually leave their parents when they get married, thus their education is only a financial asset to the in-laws and not to blood relatives. In some cases girls withdraw from school to join the labour market or to be married in order to raise money for school fees for their brothers. Since most of the general contributing factors leading to low participation of girls at all levels of education are known and fairly well researched on, this study focuses on the variables that impinge on the educational and occupational aspirations of girls, who survive in primary school and manage to embark on the secondary level of education. Researchers such as Pavalko (1971), Chivore (1989) and Kibera (1993) have supported the proposition that girls have lower educational and occupational aspirations than boys.Secondary school girls are targeted in this study. This is because the secondary cycle of education forms an important turning point in an individual’s educational and occupational options. As a minimum it forms a foundation for higher education, which is closely linked with occupational choice. Bruce (1996) asserted that to highest education and college especially education gives an individual a variety of occupational choices, and in particular white – colour and professional fields.

2. Statement of the problem

It is important to find out why girls appear to be “unconcerned” about the glaring benefits of education. As long as the majority of girls fail to proceed with formal education beyond secondary level and as long as college level of education is used as a major criterion in the distribution of well-remunerated jobs and leadership positions, they will continue to be marginalised. Lack of education or acquisition of limited education among women who in Kenya and most other countries constitute over 50 per cent of the total population, leads to their inequality representation in all facets of the society including employment, politics, and inevitably in decision making organs like Parliament. Researches have been carried out about factors militating against the education of girls but these studies do not address directly the problem being investigated (Bruce 1996). Therefore this study was designed to find out the factors militating against the education of girls in Lower Eastern Province Kenya.

3. Objectives of the study

The following objectives guided the study● To establish secondary school girls’ occupational aspirations● To determine the relative effects of different variables that are associated with lower educational aspirations of girls● To find out whether career aspirations of girls change as they move from Form One to Form Three● To determine the factors behind the educational aspirations of girls at secondary school level of education● To examine what occupational aspirations of males and female at secondary School level hold for their potential spouses.

4. Significance of the Study

The results will help interventionists in the education of girls to locate where help is required most. The research will help in emphasising equality bearing in mind socio-cultural factors such as gender stereotypes, negative traditional beliefs, attitudes and practices, patriarchal system and religious beliefs. The research will help to promote gender equity and equality in education, training and research to contribute to economic growth and sustainable development. The research will facilitate more researches in similar institutions in different set-ups.

5. Research Design

The research design used in this study was descriptive survey. The study aimed at collecting information from respondents on their opinions in relation to the various factors impacting on the education of girls. The tool that was employed in the initial identification process was door-to -door survey in the purposely sampled schools. In an effort to establish the relative impact of the various factors impacting on the education of girls, the researcher used both qualitative and quantitative methods of research.

6. Study Location

The study was carried out in Lower Eastern Province of Kenya. The Eastern Province was purposely selected because it is the largest province in Kenya. Convenience Sampling was used to select the districts that Participated in the Study. The districts whose secondary school students were represented in the study included: Machakos, Makueni, Kitui, Mwingi, and Yatta.

7. Target Population

The target population was Form Threes and Form Ones in Lower Eastern Province. The subjects of the study were drawn from the selected Districts. The respondents included Form Threes and Form Ones from the purposely selected schools. The respondents were sampled from Form One and Form Three in order to establish whether educational aspirations of Form Ones were similar to those of Form Threes.

8. Sample Size and Sampling Procedures

Purposive sampling was used to select ten secondary schools in the five districts. Using this method of sampling, two schools per district were selected. Using an administrative map of Kenya, the schools were categorised into five geographical zones with their towns as point of accessibility. Stratified sampling technique involved identifying groups in the population; the population were Form Threes and Form Ones. The samples from each group were then randomly selected. The sample was proportionally selected on the basis of equal number from each group. Stratification ensured that different groups of population were represented in the sample. Simple random sampling provided equal chance to every member in the population to be included in the study. The lottery system was used in which names of subjects were written on pieces of paper and placed in a container. The lottery was then drawn. This method helped to reduce biases or prejudices in selecting the samples. The respondents were sampled from Form One and Form Three in order to establish whether educational aspirations of Form Ones were similar to those of Form Threes. Towards enhancement of comparative dimension, boys in similar classes as girls were included in the study. Using simple random sampling 26 girls were selected from ten schools, 13 from Form One and 13 from Form Three, and 29 boys from the ten school 15 Form Ones and 14 Form Threes. The sample had 260 girls and 305 boys from purposely sampled schools. To maintain the confidentiality of the schools, a number was used to identify each school.

9. Instrumentation

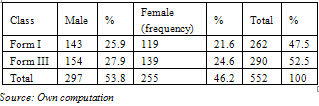

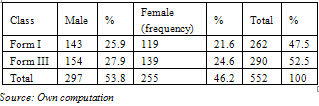

The questionnaire was the main instrument used in this research. The questions were both close and open-ended. The questionnaires were used as tools for collecting data from the sample population. For these questionnaires there was an introductory letter for the study, the importance of the respondent’s contribution to it and the assurance that the information will be handled ethically. Filling in the name was left optional so as not to make any respondent shy off. The questionnaire administered to secondary school students, sought information about their demographic background, their ratings on the factors listed by the researcher militated against their educational advancement, or their educational and occupational aspirations. They also supplied data pertaining to their desire to attain a particular level of education.Table 1. Sample of Student Respondents by Gender and Class

|

| |

|

10. Data Collection Procedures

The researcher used both primary and secondary data. Primary data was obtained using questionnaires. The questionnaires were administered and collected by the researcher and two research assistants who had been recruited. A questionnaire was administered to randomly selected girls in secondary schools from five administrative districts of the Republic of Kenya. Direct contact with schools allowed instructions on how to complete the questionnaires and assure the respondents the confidentiality of their responses. This personal involvement was an important factor in motivating the participating schools to respond more readily than if the questionnaires had been mailed to them. Secondary data was found from journals and books. Data analysis in Table 1 contains the sample of students by gender and class.

11. Data Analysis Procedures

Descriptive Statistics were used in data analysis. All answers collected from the field were coded. The data was coded by categorisation, quantification, and processing. It was tabulated using both quantitative and qualitative methods. Tables of frequency distribution were used to show the different patterns of data categories.

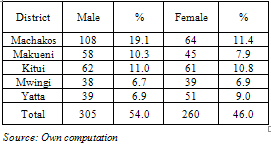

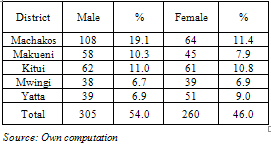

12. Presentation of the Research Findings Student’s Demographical Information and Location of the School

The sample comprised 565 students, 305 of whom were males (54%) and 260 females (46%). Data analysis of the demographic information in the questionnaire showed that the students’ age range was between 15 and 19 years. Slightly over 21% attended all-girls schools, 26% all-boys schools, and the rest 53% were in co-educational secondary schools. The marital status of the students’ parents was as follows: 88.9% were married, 4.4% divorced, and 7.7% were single parents. The majority of students (95.1% and 1.3%) were of Christian and Muslim faith, the rest (3.6%) belonged to other faiths. The data of the schools attended by the respondent by district and gender, geographical region is contained in Table 2 for more information.Table 2. Respondent by District and Gender

|

| |

|

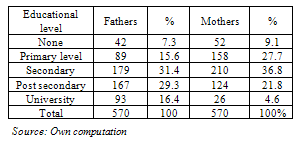

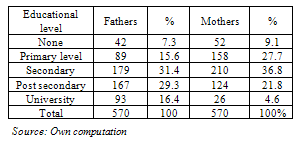

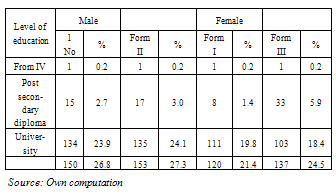

Data analysis regarding students’ social-economic status as indicated by their fathers’ and mothers’ level of education. It is evident that they generally come from low socio- economic status. In this study parents with post-secondary diploma and university are few as indicated in the table 3. Parents with post-secondary diploma and University degree correspond to middle and high socio- economic status. Those with secondary education and below are put in low socio-economic category. Table 3 presents the educational levels of the students parents.Table 3. Level of Education of Parents

|

| |

|

Data analysed in Table 3 has shown that fathers of the students targeted in this study were more educated than mothers at post-secondary and university level. Thus 7.3% of fathers have no formal schooling compared to 9.1% of the mothers. At primary, post secondary and university level, fathers constituted 15.6%, 31.4%, 29.3%, and 16.4% respectively. The corresponding percentages of mothers were 27.7%, 36.8%, 21.8%, and 4.6%. These results are not surprising because women form over 60 percent of the illiterates in Kenya. (Republic of Kenya 1988).

13. Determinants of Girls’ Educational Advancement at Secondary Cycle of Education

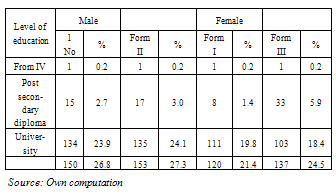

After analysing and examining students’ demographic and socio-economic characteristics, attention was focused on the factors that impinged negatively on the educational career of both girls and boys. With respect to the factors militating against the education of girls, pregnancy was rated first with 96.2%, followed by peer pressure with 85.8%, lack of school fees 79.2%, lack of parental guidance (77%), drug addiction (74.5%), Intimate boy/girls relationship (73.4%) forced early marriages, (68.9%) lack of interest and laziness in school work (65.8%), too much pocket money form parents (49.1%), cultural beliefs that do not value education of girls (42.3%), discouragement from teachers (31.6%), and fear of being in the same class with boys (9.2%).These results clearly shown that Pregnancy is one of the greatest impediments to girls’ educational career at secondary level of education. Indeed some 100 girls get pregnant each year (government of Kenya and UNICEF, 1992). Most of these girls do not have opportunities to go back to school partly because they are bogged down by motherhood responsibilities and partly because their parents do not have resources to take care of the newly born children and also pay school fees for their other children. In fact, lack of school fees also interferes greatly with the advancement of girls education. In addition when girls who have been pregnant go back to school, they are laughed by peers and the public at large. This also discourages girls not to want to return to school after giving birth.The findings that pregnancy is considered to be a big threat to girls’ education mean that they need to be educated about management of their sexuality. Girls should also be empowered to resist peer pressure and drug addiction, for girls who succumb to drug are more likely to become pregnant due to the fact that their judgment not to engage in early sexual relationships is easily impaired. With regards to the factors that impact unfavourably on the education aspirations of boys, peer pressure (with 87.5%) had the highest rating, followed by lack of school fees (77.3%),laziness and apathy (76.7%), lack of parental guidance (75.2%), drug addiction, (62.9%) intimate boys and girls relationships (54.4%), forced marriages as a result of impregnating girls (50%), too much pocket money from their parents (48.3%), and discouragement from teacher (30.3%).A comparison of the significance of various factors that impinge on educational career across gender lines such as peer pressure, laziness, apathy, lack of school fees, lack of parental guidance, drug addiction, intimate boy/girl relationship, forced early marriages, and too much pocket money from parents has revealed that girls’ education is likely to be more seriously affected than that of boys by all the above mentioned variables with an exception of peer pressure, laziness, and apathy.The next analysis centred on students’ educational aspiration. Students who indicated that they wished to attain form IV level of education were considered to have low aspirations, post secondary diploma-moderate aspirations, and those who desired university education were associated with high educational aspirations. Data in Table 4 presents levels of education aspired by secondary school students.Table 4. Level of Education Preferred by Secondary School Students by Gender and Class

|

| |

|

According to results in Table 4 the same number of males (0.2%) and female (0.2%) in Form I and Form III desired to obtain form IV level of education. Notice, however, that a larger proportion of males in Form I (2.7%) and Form III (3.0%) than females in similar classes (1.4%) and (5.9%) respectively, wished to obtain post-secondary diploma qualification. The rest of the students (23.9%) of males in form I and (24.1%) in form III desired university education. According to the findings it would appear that aspirations for male students (Form III) to achieve university education are slightly higher than those of their colleagues in Form I.On the other hand, educational aspiration of girls in Form I are slightly higher than those of their fellow students in Form III. Thus 19.8% of girls in Form I desired university education compared to 18.4% of girls in Form III. Overall it is evident that male students have higher educational aspirations compared to female students. The findings are consistent with earlier ones of Palvalko 1971), Chivore 1986, and Kibera 1993). The results also show that Kenyan secondary school students have very high educational aspirations. This result is congruent with the Somerset (1974) and Kibera (1993).To get an insight into motives for students” desires to attain a particular level of education, they were required to provide reasons. Table 5 carries the results. Table 5. Students’ Reason for Aspiring for Particular Level of Education by Gender

|

| |

|

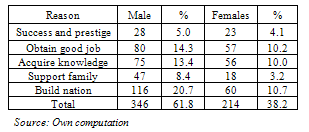

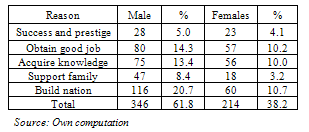

14. Factors Militating against Educational Advancement of Secondary School Students

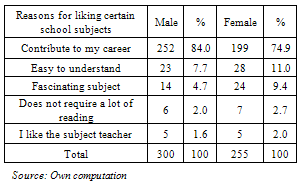

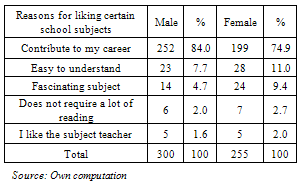

Data analysis as illustrated in Table 5, shows that students and especially males aspired for a particular level of education because they felt it would help them to build the nation. Thus 20.7% of males cited this reason. In contrast only 10.7% of the females gave the same reason. This finding is congruent with that of Kibera (1993).However, acquisition of a good job is mentioned as the next most important reason for aspiring to a particular level of education. It can be argued that an individual who is unemployed or one who does not get a well-paying job would find it difficult to have resources to contribute to nation building. By implication therefore, there is a relationship between receiving education in order to acquire a good job and the notion of nation building.The next factor cited is the desire to acquire knowledge. Around 25% of the sample 14.3% males and 10.2% females singled out this reason as motivating their educational endeavours. Other reasons that may impact on students’ educational goals are support for the family and success and prestige do not seem to be among them. Overall only 11.6% and 9.1% of the students respectively mentioned support for the family and success and prestige as motives for desiring attainment of a particular level of education.In eliciting more information about educational aspirations, of the subject studied, the student were asked to state their favourite subject and to explain why they prefer it. The reason for having interest in certain school subjects are presented in Table 6 Data analysis in Table 6 clearly shows that students preferred one subject to another because of its perceived contribution to their career. Thus 84% males and 74.9% female students stated that their favourite subject would contribute towards their future careers. Other reasons such as my favourite subject is “easy to understand” “it is a fascinating subject” “it does not require a lot of reading” and “ I like the teacher of the subject” were viewed as less important. Table 6. Educational Aspirations

|

| |

|

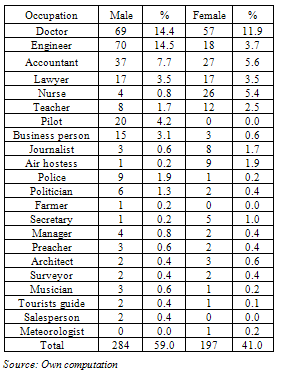

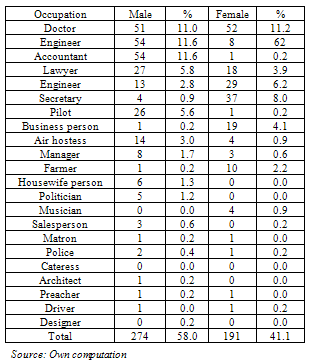

Male and female students were also asked to indicate the specific occupation they desired most. Results of the analyses are contained in table 7.Table 7. Occupation Aspired to by Gender

|

| |

|

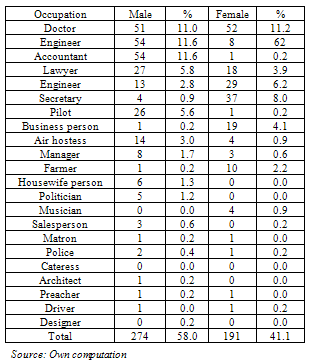

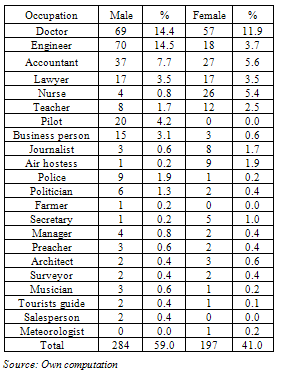

The data analysis in Table 7 shows that most preferred occupations by male students are those of an engineer (with 14.6%), followed by doctor (14.3%), an accountant (7.7%), pilot (4.2%), and lawyer (3.5%). On the other hand, the most aspired occupations by female students are that of a doctor (with 11.7%), an accountant (5.6%), nurse (5.4%), an engineer (3.7%), and lawyer (3.5%).These results in reveal that girls have lower occupational aspirations compared to their male counterparts. However, it is noted that although a good proportion of females still prefer traditional female designated occupations such as nursing, teaching, and air hostess, some females have substantial interest in male-dominated occupations such as those of engineering, medicine, and law. Further results in Table 7 reveal that both male and female students prefer white-collar occupations. None of the student wishes to enter manual technical oriented occupations such as carpentry, motor-mechanic, metal work, farm, and domestic work. These jobs are poorly remunerated and as a result they are disliked.In addition, girls on the whole require the use of the “hands” rather than the “brain” By and large Kenya’s students and the public at large distaste manual/ technical oriented occupations (Sifuna, 1976). It is noted that even though Kenya is mainly an agricultural economy, only 1.3% of the students wish to be farmers. Indeed none of the females wanted to be farmers. This is an interesting finding; women in Kenya perform over 80% of the work on the farms (Hazlewood, 1979).The Non preference of farming by female students may be attributed to the fact that they do not as a rule inherit land from their parents (Kenyatta, 1953 and Mbithi, 1974). In other words women are not “farmers”, rather they provide labour on the farms owned either by their husbands or their brothers.Further students were requested to indicate the type of occupations they preferred for their would be partners. Analysis of this information is presented in Table 8 Table 8. Occupations Preferred by Male and Female Students for Their Future Spouses

|

| |

|

The analysis in Table 8 has revealed that the majority of male respondents preferred their prospective spouses to enter “traditionally preserved” occupations for women. These occupations include those of a teacher, nurse, secretary, businesswoman, an air hostess, a farmer, and housewife. These results further show that male respondents” career choices for female students are similar to those aspired to by female students themselves.A closer look at data analysis in Table 8 also revealed that none of the male respondents wanted their spouse to be a politician or a policewoman, a driver. In addition very few wished their female counterparts to become pilots, manager, saleswomen, architects, designers, and cateresses. Nonetheless, a substantial proportion of them wanted their female colleagues to be doctors, accountants, and lawyers.Similarly, data analysis in Table 8 shows that female respondents desire their potential spouse to join “male designated” careers. These careers comprise those of engineers, lawyers, pilots, accountants, and managers. It is important also to note that career aspirations for their male counterparts are congruent with those male respondents have for themselves. From this finding, it can be inferred that females expect to gain the outcomes of good occupations in terms of remuneration and social status indirectly via their spouses and not directly through themselves. In an attempt to achieve gender parity in the occupational arena, it would be interesting to establish why girls shun male-dominated careers considering that they are better remunerated in addition to commanding high prestige and social status.

15. Results

The findings of the study have reaffirmed that girls have lower educational aspirations as compared to the boys. It has also emerged that educational aspirations of females tend to decline compared to those of their male counterparts as they move up the educational ladder. As far as occupations are concerned, by and large girls prefer to join occupations traditionally preserved for women such as those of teachers, nurses, secretaries, business women, air hostesses, farmers, and housewives. Male respondents too desire these occupations for their female counterparts. Indeed they prefer females in such occupations to be their future spouses. In contrast, females manifest higher occupational aspirations for their male counterparts than for themselves. They desire men to be doctors, engineers, lawyers, pilots, and managers. These occupations are male-dominated and are associated with good remuneration and high social prestige.Finally, the major impediments against educational advancement of girls are identified as pregnancy, peer pressure, lack of school fees, lack of parental guidance, drug addiction, intimate boy/girl relationships and forced early marriages. On the other hand boys’ educational career is affected mostly by peer pressure, followed by lack of school fees, laziness, apathy, lack of parental guidance, and drug addiction.

16. Conclusions of the Study Findings

Given that the greatest danger to girls’ education at secondary level is perceived to emanate from pregnancy, every effort must be made by parents, teachers, mentors, and school counsellors to teach them about their sexuality and its management right from the age of reason. Indeed, this study has shown that lack of school fees is relatively less important in hampering girls’ education compared to pregnancy and peer pressure.

17. General Recommendations on Girl Child Education

The findings of the study show that generally there is need to carry out awareness campaigns to sensitise all stakeholders on the importance of education, especially for the girl child. It is important to create well-maintained single-gender boarding schools. Girls should be targeted in terms of family life and sex education. There is need to create projects and programmes that will increase the family income hence result in material empowerment. This will help parents to generate more income. The fund may help in financing to get rid of the laws that prohibit negative practices such as early marriages, female genital mutilation and sexual harassment leading to early and unplanned pregnancies. Equality should be emphasised bearing in mind socio-cultural factors such as gender stereotypes as gender roles, negative traditional beliefs, attitudes and practices patriarchal descent system and religious beliefs. Further research in other institutions should be done.

References

| [1] | Bruce, KE.,1966, “Academic Ability Higher Education and Occupation Mobility”,American Sociology Review, 30th October,pp. 735-746 |

| [2] | Chivore, B.R.S.,1986, “form IV pupils’ perception and Attitudes towards the Teaching Profession in Zimbabwe” Comparative Education, Vol. 1.22,PP. 252-258 |

| [3] | Government of Kenya and UNICEF.,1992, Children and Women in Kenya, A Situation Analysis. Nairobi: UNICEF, Kenya Country Office |

| [4] | Hazelwood A., 1979, The Economy of Kenya: The Kenyatta Era. New York: Oxford University Press |

| [5] | Kenyatta Jomo.,1953, Facing Mount Kenya. Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau |

| [6] | Kibera, W.L.,1993, Career Aspirations and Expectations of Secondary School Students of 8-4-4 System of Education in Kiambu and Kajiado and Machakos Districts, Kenya: PhD.Thesis. Kenyatta University |

| [7] | King, Elizabeth.,1991, Wide Benefits Seen From Improved Education For Women.Washington Economic Reports. Nairobi: United States Information Agency No 4 |

| [8] | Mbithi, P., 1974, Rural Sociology and Rural Development; its Application in Kenya. Kampala: East African Literature Bureau |

| [9] | Mueleer, Josef.,1990, Literacy- human right not a privilege” inDevelopment and Cooperation. Berlin German Foundation for International Development |

| [10] | Palvalko, R.M.,1971, Sociology of Occupations and Professions. Hossea Lions: F.E Peakcock Publishers, inc |

| [11] | Republic of Kenya.,1998, Economic Survey. Nairobi: Government Printer |

| [12] | Republic of Kenya (1988) Literacy Survey. Nairobi: Government Printer |

| [13] | Sifuna, D.N., 1976, Vocational Education in Schools, A Historical Survey of Kenya and Tanzania. Nairobi: East African Bureau |

| [14] | Somerset H.C.A .,1974, “A Survey on Fourth Form Pupils on Educational and Occupational Expectations” In Court and Dharam, Education, Society and Development: New Perspectives from Kenya. Nairobi: Oxford University Press |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML