-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2011; 1(1): 1-8

doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20110101.01

Exploring Binge Eating and Physical Activity among Community-Dwelling Women

K. Jason Crandall 1, Patricia A. Eisenman 2, Lynda Ransdell 3, Justine Reel 4

1Department of Kinesiology and Health Promotion, Kentucky Wesleyan College, 3000 Frederica Street F.O.B. 19

2College of Health, Department of Exercise and Sport Science, University of Utah

3Department of Kinesiology, Boise State University

4Department of Health Promotion and Education, University of Utah

Correspondence to: K. Jason Crandall , Department of Kinesiology and Health Promotion, Kentucky Wesleyan College, 3000 Frederica Street F.O.B. 19.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The primary aim was to understand physical activity (PA) changes throughout the life spans of binge eating disordered (BED) participants. A secondary aim was to determine if barriers exists that limit PA participation. METHODS: Females (N=312) were recruited within the continental United States and self-administered questionnaires. BED participants (n=18), subclinical BED participants (n=19), and non-BED overweight controls (n=19) were identified. Demographic variables, PA levels, and exercise perceived benefits and barriers scores were compared. RESULTS: BED individuals reported lower PA levels during the young adult and mature adult periods when compared to non-BED body weight matched controls. Significant differences were found between BED individuals and controls for six benefits and barriers questions (p < .05). BED individuals have lower PA compared to controls during periods of the life span, and exercise benefits and barriers are significantly different. Specific barriers need to be addressed if PA is to be used as an adjunct treatment for BED individuals.

Keywords: Binge Eating, Exercise, Physical Activity, Eating Disorders

Cite this paper: K. Jason Crandall , Patricia A. Eisenman , Lynda Ransdell , Justine Reel , "Exploring Binge Eating and Physical Activity among Community-Dwelling Women", International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2011, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20110101.01.

1. Introduction

- Binge Eating Disorder (BED) is an eating disorder characterized by episodes of binge eating without inappropriate compensatory behaviors such as excessive exercise, vomiting, or laxatives (Wonderlich, Gordon, Mirchell, Crosby, & Engel, 2009). Prevalence rates for BED have been found to be as high as 40% in weight management samples and as low as 2% in the general population (Dingemans, Bruna, & Furth, 2002). Individuals with BED tend to be overweight or obese due to binge eating episodes without the accompanying energy expenditure or purging methods (Brownley, Berkman, Sedway, Lohr, & Bulik, 2007). Overweight or obese individuals who are diagnosed with BED demonstrate significantly more psychopathology and dietary disinhibition when compared to non-BED obese individuals (Grilo, White, & Masheb, 2009). BED individuals also exhibit excessive concern with their body shape and lack of thinness, become overweight at a younger age, and spend more time on dieting efforts compared to their non-BED counterparts (Grilo et al., 2009). Due to these differences, obesity prevention approaches need to address the unique problems associated with obese BED individuals (Argas, 1995; Levine & Marcus2003). A key component of weight management programs, and a potential treatment for individuals with BED, is participation in structured or unstructured physical activity (PA) (Donnelley et al., 2009). Crandall and Eisenman (2001) asserted that PA has the potential to positively support the treatment of BED.Historical PA patterns in individuals with BED are unknown. Researchers have shown that BED participants become overweight, begin dieting, and first meet the criteria for BED in early adolescence (Brownley et al., 2007). Overweight binge eating children also show greater levels of obesity and more psychopathology compared to overweight children who do not binge eat. The current PA patterns of BED individuals who are not in treatment are unknown. There are no data are related to the type, frequency, duration, and overall level of PA. A review of the literature determined that overall energy expenditure, including activity-induced thermogenesis, in BED individuals has yet to be consistently identified (de Zwaan, Aslam, & Mitchell, 2002). Although researchers have examined PA levels, energy expenditure, and perceived benefits and barriers to PA in individuals with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, this important information has yet to be elucidated in BED individuals (Davis et al, 1997). To date, two investigations have been conducted to determine the effects of structured PA on BED. Participants were instructed to walk between 3 and 5 days per week (expending ~1,000 kcals/wk) for 6 months (Levine, Marcus &, Moulton, 1996). After a 6- month intervention, binge episodes were significantly decreased, however, body weight and depression did not change. Leisure time structured exercise was used in conjunction with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (Pendleton, Goodrick, Poston, Reeves, & Foreyt, 2002). One hundred fourteen obese female binge eaters were randomized into four groups: (a) CBT with exercise and maintenance, (b) CBT with exercise, (c) CBT with maintenance, and (d) CBT only. The maintenance component consisted of 12 biweekly meetings over a period of 6 months after cessation of treatment. Eighty-four women completed the 16-month study. Participants in the exercise groups were expected to participate in a minimum of 45 minutes of cardiovascular exercise three times per week for 4 months. Two of the sessions each week were completed at an exercise facility, and the third session was completed at home. At the end of the study, the exercise groups had greater reductions in binge days compared with the non-exercise groups at 4 months, 10 months, and 16 months. The exercise groups attended an average of 16 out of a possible 32 exercise facility sessions. The exercise groups self-reported significantly more leisure time PA at the end of 4 months; however, when compared to the nonexercise groups at 10 and 16 months, no significant differences were found. Despite attending only half of the exercise facility sessions and reporting only slightly more PA levels than the nonexercise groups, the exercise groups significantly reduced binge eating episodes and experienced improvements in mood and reductions in body mass index as compared to the nonexercise groups. Possible improvements in physiological measures such as reduced body fat levels, blood glucose levels, blood pressure, and cholesterol were not monitored; therefore, it is unclear if the exercise training program affected risk factors for hypokinetic diseases. Other areas not addressed in the study included the limited quantification of PA, a lack of information about the relationships between formal PA instruction and binge eating status, and a lack of information about the low adherence to the exercise program. The results of these studies suggest that formal PA instruction may be an effective addition to BED treatment. However, structured physical activity interventions may be premature until more systematic research is conducted to better understand the role historical and current physical activity plays in the lives of BED individuals (Davis et al., 1997).Historical PA patterns in BED participants are unknown. Researchers have shown that most BED participants become overweight, begin dieting, and first meet the criteria for BED in early adolescence (Brownley, et al., 2007). Overweight binge eating children also show greater levels of obesity and more psychopathology compared to overweight children who do not binge eat (Morgan et al., 2002).The current PA patterns of BED individuals not in treatment are unknown. There are no data related to the type, frequency, duration, and overall level of PA. A review of the literature determined that overall energy expenditure, including activity-induced thermogenesis, in BED individuals has yet to be consistently identified. Although researchers have examined PA levels, energy expenditure, and perceived benefits and barriers to PA in individuals with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, this important information has yet to be elucidated in BED individuals (Davis, 1997).Lifestyle or unstructured PA has been successfully utilized in other populations to increase long-term adherence to PA and to improve physiological outcomes such as cardiovascular endurance (Dunn, Garcia, Marcus, Kampert, Kohl, & Blair, 1998) (Dunn, Marcus, Kampert, Garcia, Kohl, & Blair, 1999). The addition of unstructured PA may be an important addition to treatment or a protective factor from excess body weight commonly associated with BED. A paucity of information describes the historical and current PA participation of BED individuals. Given the need for additional information on individuals with BED, the primary aim of this study was to better understand how PA involvement changes throughout the life spans of BED participants, subclinical BED participants, and non-BED overweight controls. A secondary aim was to determine if perceived barriers exist that might limit PA participation in these groups. The findings from this study may aid in the promotion of structured and unstructured PA as an adjunct treatment for BED.

2. Methods

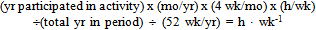

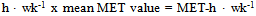

- ParticipantsPhase I: Females (N=312) between the ages of 18 and 50 were recruited from communities within the continental United States with the goal of obtaining a convenience sample of 75 participants who met all five criteria for BED. Recruited from multiple sources, including religious organizations, educational groups, and eating disorder treatment groups, all participants were self-administered a series of questionnaires. A cover letter accompanied the questionnaires and informed participants that completion of the questionnaires indicated their consent to participate in the study. The questionnaires consisted of a (a) Demographic Questionnaire; the (b) Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised; the (c) Exercise Benefits To Barriers Scale (EBBS); and the (d) Bone Loading History Questionnaire (Yanovski, Nelson, Dubbert, & Spitzer, 1993) (Kriska, Sandler, Cauley, Laporte, Hom, & Pambianco 1988) (Dolan, Williams, Ainsworth, & Shaw, 2006). Following is a more detailed description of each questionnaire.Questionnaire on Eating and WeightPatterns-Revised The Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised (QEWP) was chosen to screen participants for binge eating status. The QEWP, a four-page questionnaire that contains 28 items, was developed to diagnose BED using DSM-IV-TR criteria (Yanovski, 1993).Diagnoses are based only on the responses to 13 out of a possible 28 items. These 13 items classify individuals into one of four categories: (a) BED, (b) purging bulimia nervosa, (c) nonpurging bulimia nervosa, or (d) not classified as a binge eater. Reported internal consistency was .75 in a weight control sample and .79 in a community sample (Morgan et al., 2002).The QEWP derived diagnosis of BED has also been reported to agree with the structured interview diagnosis (kappa = .57) (Johnson & Torgrud, 1996) (Pratt, Telche, Labouvie, Wilson, & Agras, 2001). The QEWP contains a question that ascertains binge eating severity or the average number of binge eating episodes per week in the last 6 months. Possible responses are 1 = less than 1 day per week, 2 = 1 day per week, 3 = 2 or 3 days per week, or 4 = 4 or 5 days per week or nearly every day (Yanovski, 1993). Participants self-reported body weight and height for the calculation of body mass index.Exercise Benefits To Barriers ScaleThe Exercise Benefits to Barriers Scale (EBBS) was used to determine the participants’ perceived benefits and barriers to exercise (Sechrist, Walker, & Pendler, 1987). Containing 40 items, the EBBS uses a 4-point, forced-choice, Likert-type format to obtain an ordinal measure of the strength of agreement with item statements. Benefits were scored as 4 = strongly agree, 3 = agree, 2 = disagree, and 1 = strongly disagree. Barriers were reverse scored. Two scores were calculated: (a) total benefits (EBBSben) and (b) total barriers (EBBSbar). The possible range of scores on the EBBSben is between 29 and 116, with most scores falling between 51 and 116. On the EBBSbar the possible range of scores is between 14 and 56, with most scores falling between 14 and 56. The standardized Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients were .953 for the EBBSben and .886 for the EBBSbar (Vuillenium et al., 1987). Bone Loading Health QuestionnaireThe Bone Loading Health Questionnaire (BLHQ) was designed to ascertain historical PA specific to bone (Cronbach’s alpha was .86) (Dolan et al., 2006).To measure both historical and current PA in the participants, the BLHQ was modified so that frequency, intensity, and duration could be recorded for the specific PAs performed during the identified time periods: (a) elementary school, (b) junior high school, (c) high school, (d) young adult (18 to 29 years old), and (e) mature adult (30 to 50 years old). For the school-age time periods, PA during school hours and leisure time PA were ascertained. Leisure time PA was determined for the young adult and mature adult time periods. Participants were provided with a sample list of PAs. These activities included structured activities (e.g., basketball and volleyball) and lifestyle or unstructured activities (e.g., gardening and hiking). Occupational PA was not measured with the BLHQ. Two outcome measures for PA were calculated: (a) mean hours per week (h • wk-1) and (b) mean metabolic equivalent unit (MET) hours per week (MET-h • wk-1).Detailed information was collected for frequency and duration of each PA. Participants indicated the number of months per year of participation and the number of years of participation during each time period. Mean hours per week of PA were calculated by summing the hours of participation for all activities (see Equation 1) (Pendleton et al., 2000). The estimated metabolic cost of PA participation during each time period was obtained by multiplying the number of hours by its estimated metabolic cost (MET) (see Equation 2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

3. Results

- All analyses were performed using SPSS. Multiple one-way ANOVAs were used to compare age, body mass index, current body weight, highest body weight, exercise benefits to barriers scale scores, and PA levels (h • wk-1; MET-h • wk-1) among groups. No significant differences were found in body mass index, current body weight, highest body weight, exercise benefits to barriers scale scores, or MET-h • wk-1 (see Table 1). Significant differences were found among groups in h • wk-1 for the high school, young adult, and mature adult time periods (see Table 2). Table 3 presents the most common PAs for the BED group during each time period.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The primary aim of this study was to better understand how PA involvement changes throughout the life spans of BED individuals. The findings revealed that during elementary school and junior high school, BED individuals did not differ from the subclinical or non-BED overweight controls. Statistically significant differences did not exist for high school PA among BED individuals and non-BED overweight controls. However, the BED individuals reported 2.2 and 3.9 more hours of PA per week as compared to non-BED overweight controls and subclinical BED participants, respectively. In addition, the BED individuals and the subclinical BED individuals reported beginning to binge eat in high school at the mean age of 18 y, whereas the overweight controls did not report a binge episode until young adulthood at the age of 23 y. During junior high school and high school, adolescents, particularly females, begin to compare their bodies to others (Ransdell, Wells, Manore, Swan, & Corbin, 1998). The possibility exists that BED individuals may have used PA during high school to compensate for the binge eating episodes initiated during high school. BED individuals have been known to infrequently compensate for binge episodes, exhibiting symptoms of nonpurging bulimia nervosa. Determining if PA is used during high school to compensate for binge eating should be an objective for future research. A related finding was the significantly lower PA levels reported during the young and mature adult periods for BED individuals as compared to non-BED controls. During high school, opportunities for PA within the school setting are more available and family and work responsibilities are relatively few. Researchers have shown that family and work responsibilities limit PA participation thus, the combination of more PA opportunities and fewer responsibilities allows for individuals to be more physically active during high school (Sherwood & Jeffery, 2000). All of the groups examined in this study were more active in high school as compared to the young and mature adult periods. Therefore, it appears BED participants were physically active as children and became less active as young adults and mature adults without concurrent reductions in caloric intake. Increases in body weight later in life are likely due to these lifestyle changes, therefore future research is needed to determine if PA may affect early binge eating and the weight consequences of BED.Other important questions can be addressed using the PA data of BED individuals from this study. First, it is important to determine if BED participants were physically active in elementary school, junior high school, and high school in sufficient amounts to produce significant health benefits. Second, it is important to determine if BED participants are receiving sufficient amounts of PA for weight management as adults. Finally, comparisons of BED participants’ PAs with data from other populations can provide a more descriptive picture of their PA patterns.The BED participants in this study reported an average of 55.37 minutes of PA per day during elementary school and an average of 51.60 and 71.57 minutes per day during junior high school and high school, respectively. The Centers for Disease Control recommends that elementary school students receive a minimum of 60 minutes a day of moderate and vigorous PA, whereas junior high school and high school students should accumulate a minimum of 30 minutes a day (CDC, 2007). From the current study, it appears that BED participants received more than sufficient amounts of PA during their school-age years to produce health benefits, but future research, including objective measurement of PA in this population, is needed to determine if BED individuals use PA to compensate for binge eating episodes.The BED participants in this study participated in an average of 2.25 h • wk-1 of PA at an average intensity of 4.9 METs and 1.1 h • wk-1 at an average intensity of 5.01 METs during their young adult and mature adult years, respectively. Donnelly and colleagues (2009) recommended that overweight and obese individuals progressively increase PA from 3.3 h • wk-1 to 5 h • wk-1. Increasing PA participation to greater than 5 h • wk-1 may facilitate improved long-term maintenance of weight loss.7 From these results, it appears that BED participants participated in sufficient amounts of PA for reductions in chronic disease risks during their young adult years, but did not participate in recommended amounts to facilitate long-term weight maintenance. PA participation during their mature adult years was almost 6 h • wk-1 less than recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine for weight maintenance.The reductions in PA and intensity over the life span found in this study are similar to those found in other studies (CDC, 2007).It is difficult to ascertain from the present study the reasons for the reductions in PA throughout the life span; however, the barriers found from administration of the EBBS provide evidence that specific barriers may affect PA levels of BED individuals. A closer examination of the types of PAs participated in by the BED participants across the life span may help to clarify issues related to reduced PA and intensity. As participants grew older, their PAs became less structured. Expectedly, children’s games were the predominate activities listed during elementary school age, whereas structured activities such as basketball and softball were popular during junior high school age. As the participants moved into high school, their activities became less team or sport oriented and more fitness oriented (e.g., jogging and walking were the most popular reported activities). As young adults (18 to 29 years old), aerobic dance and softball were popular. Mature adults (30 to 50 years old) participated in more unstructured or lifestyle activities such as walking, hiking, and gardening. Because the participants reported a greater number of unstructured or lifestyle activities, it may be helpful to prescribe these types of PAs during BED treatment. The high body mass indices, body weights, and highest body weights reported for the BED participants are in agreement with values reported by other researchers (Dingemans et al., 2002). These results are not surprising because individuals meeting the diagnostic criteria for BED report high caloric intakes as a result of their binge eating episodes (Gueritn, 1999).The World Health Organization classification scheme defines overweight as a body mass index between 25 and 29.9, whereas obesity is set at a body mass index of 30 and above (Westerterp, 1999). When the BED participants for this study were compared to these standards, 17% of the sample was considered overweight and 61% were obese. No significant differences were found in perceived benefits to barriers scores among any of the groups. Ransdell and colleagues (1998) examined changes in perceived benefits and barriers as a result of participation in home-based and university-based PA interventions. Prior to the intervention, the baseline-perceived benefits to barriers scores were similar to the participants in this study, suggesting that significant and practical differences do not exist between BED participants and other populations when composite scores for perceived benefits and barriers are used. However, there are significant differences when specific perceived barriers are examined separately. Specific perceived barriers were identified by BED participants that were significantly different from subclinical BED participants and controls. BED participants believed that (a) exercise costs too much, (b) exercise takes too much time, (c) exercise takes too much time away from family, (d) exercise facility schedules inconvenient, (e) family members do not encourage exercise, (f) people look funny in exercise clothes, and (g) too few places to exercise. In a comprehensive review, Sherwood and Jeffery stressed the importance of addressing prominent barriers and enhancing social support to PA to ensure long-term adherence (Sherwood, 2000). Because these barriers have not been described in the BED population, they can now be addressed during the design and implementation of PA interventions for BED participants to improve both the initiation of PA and adherence to programs. An important overall finding from the present study is that there were differences in specific perceived barriers to exercise between the BED participants and the subclinical BED participants. Crow and colleagues questioned whether or not the diagnostic criteria for BED make meaningful distinctions between full and partial (subclinical) cases of BED (Fitzgibbon & Blackman, 2000). They found that 30% of bulimia nervosa cases were incorrectly classified as BED, and 17% of BED cases were incorrectly classified as bulimia nervosa. Others have concluded that the current diagnostic criteria are sufficient to delineate between BED and bulimia nervosa (Crow, Agras, Halmi, Mitchell, & Kraemer, 2002) (Streigel-Moore et al., 2001). The results of this study provide evidence that the diagnostic criteria do delineate between BED and partial BED. Because the two groups differed in perceived barriers to exercise in this study, this variable may be a useful addition for the identification of BED. The descriptions of PA levels, intensities, perceived benefits of and barriers to PA, and common PAs across the life span are informative because there is no previous research describing these variables in BED participants. The PA levels reported by BED participants in this study were not sufficient to produce significant weight loss or to reduce the risk of weight gain over time (Donnelley et al., 2009).The results must be interpreted with caution due to specific limitations associated with the exploratory nature of this study. First, difficulty in recruiting BED participants resulted in a lower than expected sample size. Second, a newly developed mechanical bone loading questionnaire was used to measure energy expenditure. An existing questionnaire with established validity and reliability may have been a better choice for the measurement of energy expenditure, particularly with overweight or obese individuals.Factors related to PA program adherence were a major focus of this investigation. Specific perceived barriers to PA were identified in BED participants, yet many questions remain related to these barriers. Further exploring the PA perceptions of BED participants would be an important next step in answering these questions. Determining how the participants defined PA, their attitudes about PA, and their eating patterns related to PA could aid in optimal PA programming. Finally, because the tool contained a limited number of possible barriers that the participants could choose from in the EBBS, there may be other perceived barriers yet to be identified. Modification of the EBBS to include these potential barriers may provide information that could be used to design a more optimal PA intervention. In combination, all of this information could be used to design PA interventions for BED participants that incorporate the latest in behavioral research (Ransdell et al., 1998). Future research should attempt to apply qualitative research methodologies to enrich one’s understanding of the quantitative data from this study. The following questions need to be answered. How do BED participants define PA? What are BED participants’ attitudes about PA? How are BED participants’ eating patterns related to PA? What effect could these eating patterns have on optimal PA programming?

5. Conclusions

- The objective of this study was to better describe how PA involvement changes in BED individuals throughout their life span. In addition, BED participants’ perceived benefits of and barriers to PA were assessed to determine if barriers existed that might limit PA participation. BED participants did not significantly differ in body mass indices, current body weights, or highest body weights. No significant differences were found in mean MET hours per week; however, significant differences were found in mean hours of PA per week. Significant differences were found in perceived barriers to exercise between BED participants and controls. It can be concluded that BED participants are physically active as children and adolescents. The BED participants reported beginning to binge eat in high school around the age of 18 y. BED participants participated in sufficient amounts of PA in high school, but the possibility does exist that PA was used to compensate for binge eating episodes. Large reductions in PA were found after the participants left high school. Although not completely sedentary, they did not participate in sufficient amounts of PA to produce significant health benefits or to manage body weight. The reductions in PA may be explained by the specific perceived barriers identified by the BED participants

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML