-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Networks and Communications

p-ISSN: 2168-4936 e-ISSN: 2168-4944

2026; 15(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.ijnc.20261501.01

Received: Dec. 14, 2025; Accepted: Jan. 3, 2026; Published: Jan. 7, 2026

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Good Quality of Service on Terrestrial and Satellite Network Systems Over Nigeria

Oladayo Gbolahan Ajileye1, Joseph Sunday Ojo1, Vincent Andrew Akpan2

1Department of Physics, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria

2Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Vincent Andrew Akpan, Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Rain fade presents a major challenge to maintaining quality of service (QoS) in wireless and satellite communication systems, especially at higher frequency bands (Ku and above). Severe rainfall can significantly attenuate signals, leading to transmission failures. To mitigate this, accurate modelling of rain-induced attenuation is essential for real-time adaptation of power levels, coding, and modulation through decision support systems. This study introduces a hybrid modelling approach using multilayer perceptron neural network (MLPNN) and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS), and compares the results with Synthetic Storm Techniques (SST), which simulate rain attenuation based on time-series rain rate data. A two-input, one-output model is developed to estimate rain attenuation more effectively. At a rain rate of 180 mm/hr, observed attenuation was 48 dB, while predicted values were 46.88 dB (MLPNN) and 35.92 dB (ANFIS), demonstrating the potential of AI-driven models to approximate real conditions with high accuracy. These results enable decision support systems to dynamically adjust satellite parameters, ensuring QoS and service-level agreement (SLA) compliance during adverse weather. The proposed approach offers a reliable algorithm for improving the robustness of satellite and terrestrial links under extreme weather conditions.

Keywords: Comparative Analysis, Machine Learning, Quality of Service, Terrestrial and Satellite Network

Cite this paper: Oladayo Gbolahan Ajileye, Joseph Sunday Ojo, Vincent Andrew Akpan, Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Good Quality of Service on Terrestrial and Satellite Network Systems Over Nigeria, International Journal of Networks and Communications, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2026, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.ijnc.20261501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

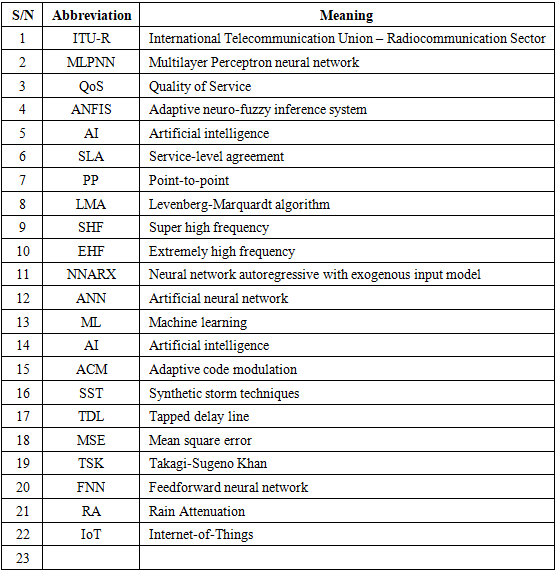

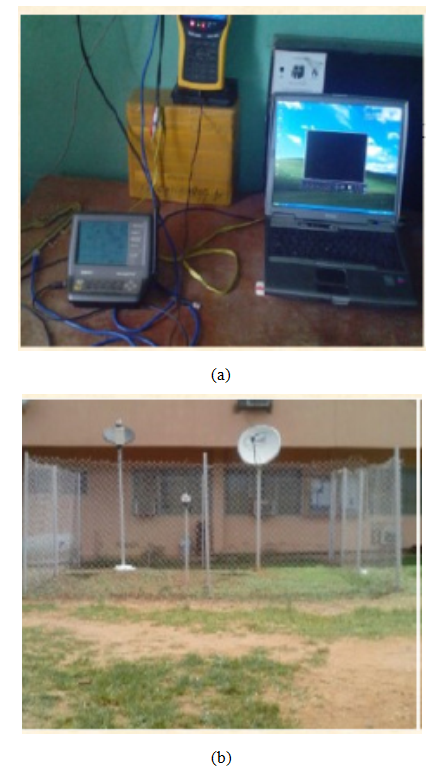

- During a period of heavy rainfall, satellite and terrestrial microwave communications that operate at frequencies higher than 10 GHz which may have signal interruptions [1]. Thus, point-to-point (PP) connectivity may impede continuous content streaming [2]. Link errors must be fully eliminated, especially during live broadcasting [3]. The signal along wireless communication networks is weakened by rain, a natural occurrence [4,5]; hence, mitigating rain attenuation is required to maintain a constant stream of content. Based on this assumption, dynamic fade mitigation strategies may be used in conjunction with fade prediction models that can predict the link's condition. In light of this, steps may be taken to guarantee that the link will remain completely operational for communication services even during a storm. Many researchers have employed an artificial neural network (ANN) for rainfall forecasting and demonstrated that the ANN may provide acceptable results after training [1,6–9]. In this study, rain attenuation is predicted and classified using the adaptive neural fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), a neural network employing a feedforward multilayer perceptron neural network (MLPNN) trained with Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (LMA) for dynamic rain attenuation mitigation.This research aims to comparatively analyze adaptive techniques for good quality of service on terrestrial and satellite network systems in Nigeria, especially during intense storms. The objectives are to deduce attenuation using 5-year rain rate data from a tropical location in Akure Nigeria (using the synthetic storm technique and ITU-R attenuation model); formulate an adaptive technique to predict and control signal to noise using hybrid adaptive measures (fuzzy logic and an artificial neural network), and further compare a proposed adaptive mitigation measure to improve Quality of Service (QoS) during intense weather conditions.The techniques presented in this research can be adapted to create a stable and effective algorithm that can effectively manage signal propagation for network service providers as well as manage the quality of signals in channels impacted by attenuation due to weather at high frequencies. It can also serve as a noticeable contribution to improving the signals transmitted via satellite networks and invariably aid in improving satellite services. Many studies have been carried out by researchers to improve the quality of service on wireless and satellite networks. Crane and co-workers carried out a researched the prediction of the effect of rain on satellite communication in temperate regions [10]. His research shows that the effect can be estimated if the distribution of rain intensity is known in both time and space. Harb and colleagues investigated the quality of service improvement in weather-impacted satellites using the Markov model to predict weather attenuation that can maintain quality of service via an intelligent awareness control system [11–14]. Nomura and co-researchers proposed a learning method of fuzzy inference in which the inference rules express the input-output relation of the data and are obtained automatically from the data gathered by specialists [15]. In this method, triangular membership functions were tuned through experience. The learning speed and generalization capabilities of this method were higher than those of a conventional back propagation neural network. Dhafer and co-workers also investigated how to simplify the factors for an ad-hoc network on mobile phones using fuzzy techniques, and it was deduced that higher throughput does not usually mean a high quality of service [8]. Furthermore, the system developer expressed the knowledge acquired from the input-output data in the form of fuzzy inference rules. Eyob and colleagues worked on enhanced adaptive code modulation (ACM) for rainfall fade mitigation in Ethiopia, and the results show that a neuro-fuzzy inference system can be employed to enhance mitigation techniques while maintaining link availability [9]. This study aimed to adopt a hybrid-adaptive mitigation measure to maintain the quality of signals along the terrestrial and satellite propagation links in a tropical location. The list of abbreviations and their respective meaning are listed in Table 1.

|

2. Background Knowledge

2.1. Modelling Based on Machine Learning Using Experimental Data

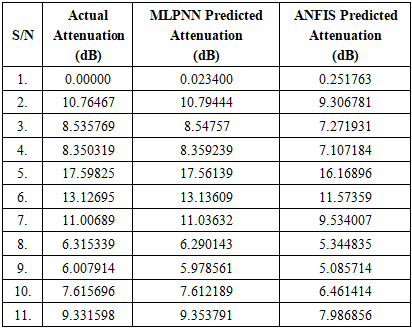

- The goal of machine learning (ML), a division of artificial intelligence (AI), is to create systems that can learn from the data they consume and enhance their performance. Artificial intelligence is a general term that describes robots or systems that can imitate human intellect. Every learning strategy is data-driven. The system is trained using data sets. These data sets are gathered and applied to training. In this study, the system received 2732 rows of data based on rain rate measurement based on vertically-looking micro rain radar as presented in Figure 1. To validate the data used, tipping bucket rain gauge measurements from archived data of the Communication Research Group, Physics Department, Federal University of Technology, Akure have been used. It comprises of five years of rain data of one minute integration time series from 2013–2018.

| Figure 1. Setup of the micro rain radar: (a) Observatory centre and (b) micro rain radar station |

2.2. Time-Series Using Synthetic Storm Techniques

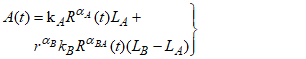

- Synthetic Storm Techniques (SST) are physical-mathematical radio propagation method that can be used to generate reliable rain attenuation time series by converting a rain rate time series at a specified site into a rain attenuation time series. Local parameters such as rain rate, length of the signal path through the rain cell, and rain cell velocity at the site under investigation are required in the SST [20]. Moreover, by applying the SST method, rain attenuation time series at any frequency and polarisation can be generated for any slant path above approximately 10 degrees, as long as the hypothesis of isotropy of the rainfall spatial field holds in the long term. The SST method is very useful for designing communication satellite systems and improving their performance for calculating rain attenuation over a satellite path. The troposphere's vertical structure divides into two levels when it rains. A is regarded as the rain layer, and B is the melting layer. The expression is given as

| (1) |

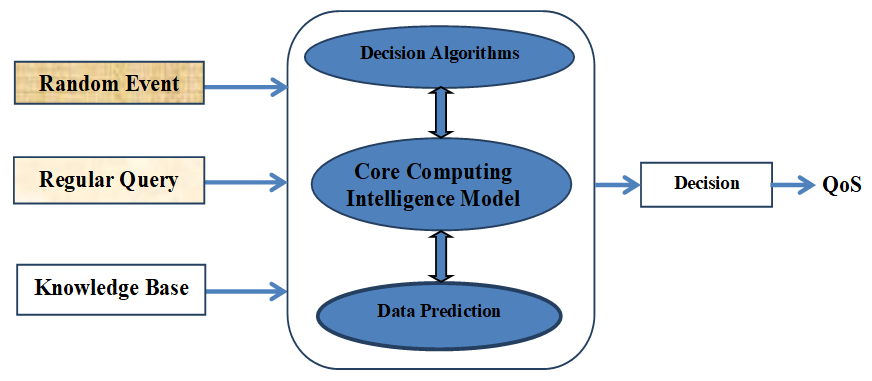

2.3. Block Diagram Description of the Proposed Machine Learning Scheme for Good QoS

- The proposed system makes use of different weather conditions (such as rain) occurring at various times are taken into account, supported by accurate background data, to enhance the effectiveness of our decision system. The block diagram of the proposed machine learning scheme uses random weather event, regular query and knowledge base in conjunction with ANFIS decision algorithms, core computing intelligent model and data prediction scheme based on neural network to determine good quality of service (QoS) as illustrated in Figure 2. This system utilizes the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm within an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) using neural network to perform predictions and decision-makings in ensuring consistent good quality of service (QoS).

| Figure 2. Block diagram of the proposed machine learning scheme for supporting decision-making in networks |

3. Adaptive Modelling Schemes and Model Predictors

3.1. The Feedforward Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPNN)

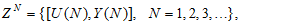

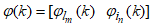

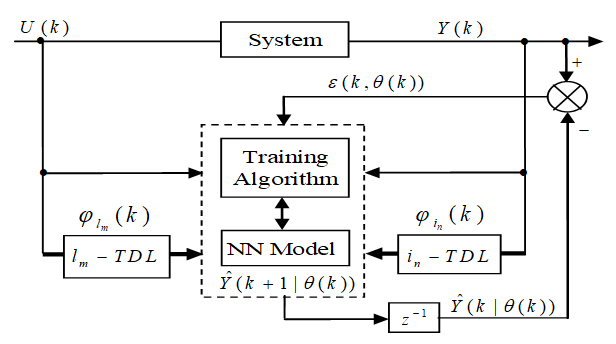

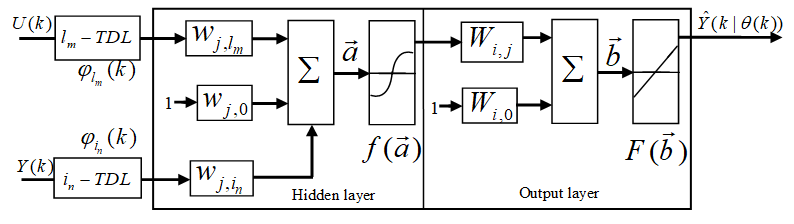

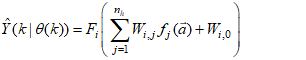

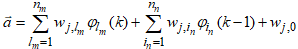

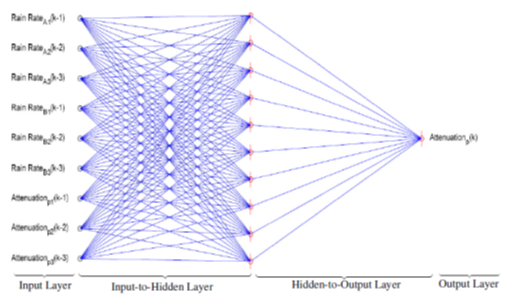

- The neural prediction scheme used in this paper is based on the series-parallel architecture shown in Figure 3 where the system is in parallel with the NN identification model (in the dashed box) and tapped delay line (TDL) denotes tapped delay line memory used to store temporal NN input information. It consists of a training algorithm and the NN model. Assuming that the input-output data pair

of the system taken over NT period of time is available [19]:

of the system taken over NT period of time is available [19]: | (2) |

in (7) is available, and m and n are known. The inputs

in (7) is available, and m and n are known. The inputs  to the NN, via an

to the NN, via an  -TDL and

-TDL and  -TDL, are the past m-inputs and n-outputs contained in

-TDL, are the past m-inputs and n-outputs contained in  which is obtained from

which is obtained from  defined in (2); where

defined in (2); where  and

and  .

. | Figure 3. Series-parallel structure for neural network model identification |

| Figure 4. Multilayer perceptron neural network (MLPNN) model architecture |

in (14) into the input and output parts as

in (14) into the input and output parts as  and

and  respectively, the output of the NN of Figure 3 can be expressed in terms of the network parameters of Figure 4 as

respectively, the output of the NN of Figure 3 can be expressed in terms of the network parameters of Figure 4 as | (3) |

and j is the number of hidden neurons;

and j is the number of hidden neurons;  and

and  and

and  are the hidden and output weights respectively;

are the hidden and output weights respectively;  and

and  are the hidden and output biases;

are the hidden and output biases;  is a linear activation function for the output layer and

is a linear activation function for the output layer and  is an hyperbolic tangent activation function for the hidden layer defined here as:

is an hyperbolic tangent activation function for the hidden layer defined here as: | (4) |

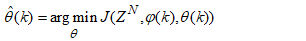

.The neural network output prediction problem then translates to a nonlinear minimization where the error estimates

.The neural network output prediction problem then translates to a nonlinear minimization where the error estimates  | (5) |

and the predictor output

and the predictor output  in (3) is minimized in some sense and used to adjust and update

in (3) is minimized in some sense and used to adjust and update  recursively to obtain an optimal parameter vector

recursively to obtain an optimal parameter vector  . The minimization of (5) to obtain

. The minimization of (5) to obtain  can be expressed as:

can be expressed as: | (6) |

is formulated as a mean square error (MSE) type cost function given as:

is formulated as a mean square error (MSE) type cost function given as: | (7) |

have also been reported [19,24–26].The training algorithm used here is the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (LMA) from the Deep learning Toolbox of the MATLAB [24]. The network training method is as follows. At time k, given

have also been reported [19,24–26].The training algorithm used here is the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (LMA) from the Deep learning Toolbox of the MATLAB [24]. The network training method is as follows. At time k, given  ,

,  , a small initial

, a small initial  as well as the available

as well as the available  and

and  ; the training algorithm then computes the a priori output estimate

; the training algorithm then computes the a priori output estimate  . At time

. At time  is available which is used to compute the a posteriori output estimate

is available which is used to compute the a posteriori output estimate  and the error (5) is used to adjust

and the error (5) is used to adjust  until

until  is obtained or certain stopping criteria is satisfied. Note that

is obtained or certain stopping criteria is satisfied. Note that  in (5) is now given by (3) and we still seek the value of

in (5) is now given by (3) and we still seek the value of  in (6).

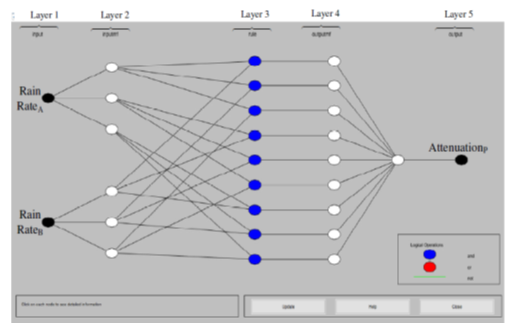

in (6).3.2. The Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS)

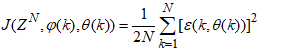

- The adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) was introduced to create a method for intelligent systems design whose behaviour or pattern inherent in a given dataset is unknown which could be obtained using neural network techniques from where fuzzy rule-based intelligence can be automatically generated and incorporated using the fuzzy inference system (engine). A typical architecture of a five-layer ANFIS is shown in Figure 5. The commonly and most widely used five-layer shown in Figure 5 ANFIS architecture including the one implemented in MATLAB® and Simulink® [24] which has been adopted for used in this study. For completeness, consistency and simplicity, each of these five layers is described below with their accompanying mathematical descriptions [27].

| Figure 5. The architecture of the five-layer ANFIS |

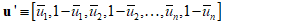

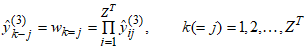

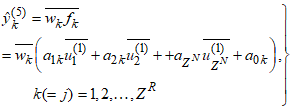

with its 2n-dimensional complement coded form u' such that:

with its 2n-dimensional complement coded form u' such that: | (8) |

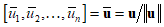

. Complement coding helps avoiding the problem of category proliferation when using fuzzy-ART for data clustering. Having this in mind, we can write the I/O function of the first layer as follows:

. Complement coding helps avoiding the problem of category proliferation when using fuzzy-ART for data clustering. Having this in mind, we can write the I/O function of the first layer as follows: | (9) |

| (10) |

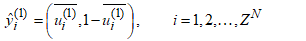

| (11) |

and implements the linear function:

and implements the linear function: | (12) |

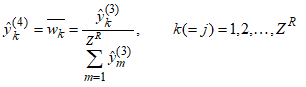

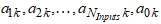

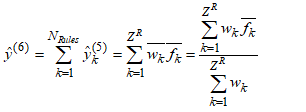

is the normalized activation value of the k-th rule calculated with the aid of (12). Those parameters are called the consequent parameters or linear parameters of the ANFIS system and are regulated by the training algorithm.Layer No.5 - Output LayerThe single node of this layer produces the output of the network, performing the weighted average defuzzification process. For the proposed HANFA-ART system, this layer consists of one and only node that creates the network’s output as the algebraic sum of the node’s inputs:

is the normalized activation value of the k-th rule calculated with the aid of (12). Those parameters are called the consequent parameters or linear parameters of the ANFIS system and are regulated by the training algorithm.Layer No.5 - Output LayerThe single node of this layer produces the output of the network, performing the weighted average defuzzification process. For the proposed HANFA-ART system, this layer consists of one and only node that creates the network’s output as the algebraic sum of the node’s inputs: | (13) |

4. Implementation and Simulation Strategies

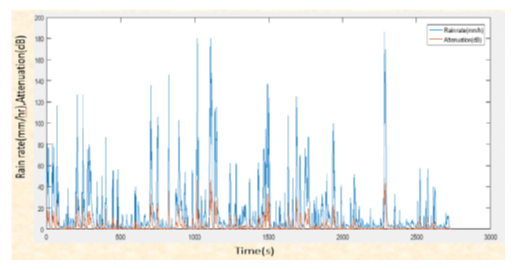

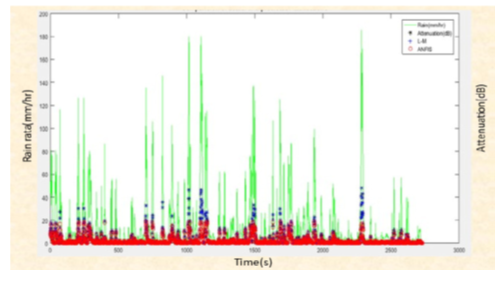

- The five-year rain rate data was evaluated using feedforward multilayer perceptron neural network (MLPNN) trained with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (LMA). Adaptive neuro-Fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), and neural network. As shown in Figure 3 is the neural architecture; the neural set-up comprises the two inputs (rain rate at layer A and rain rate at layer B) and output (Attenuation or quality of service (QoS)).In this study, both the feedforward multilayer perceptron neural network (MLPNN) predictor of Figure 3 and the Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) of Figure 5 were trained using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (LMA). The 2,731 data was split into 70% (1,911) training data for both MLPNN and the ANFIS; 15% (410) was used for validation while 15% (410) was reserved for the trained network testing [17,19,25,26]. If the output prediction (QoS) are poor, the procedure is repeated by adjusting the hidden layer neuron for MLPNN, joint weight (network weights and biases) and the number of iteration for performance improvements while maintaining the same number of three past values for performance comparison until satisfactory performance was achieved.The system is trained using the training data sets and validated using the validation data sets. These data sets are gathered and applied to training. In this instance, the system received 2732 new pieces of data. The rain rate and attenuation time series for frequency 12.25 GHz are shown in Figure 6. The relations show a trend whereby, as the rain rate increases, attenuation also rises. For example, at a rainstorm's 180.6 mm/hr over 1100 seconds time interval, attenuation was 50 dB, which had a significant impact on the propagating signal, while at a drizzle's rain rate categorization of 30.4 mm/hr, the attenuation was 5.4 dB.

| Figure 6. Time Series Rain Rate Data and Attenuation at 12.25GHz |

5. Results and Discussion

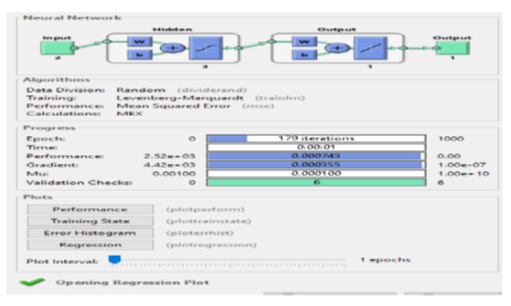

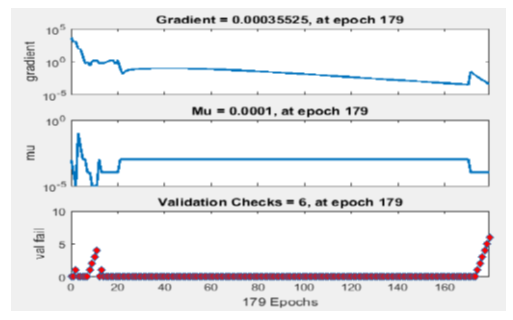

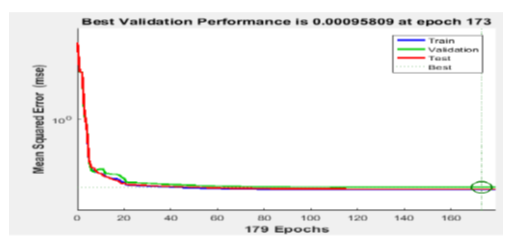

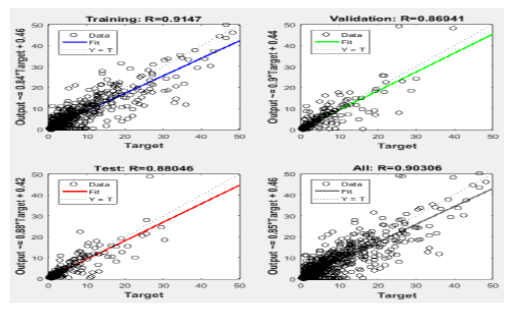

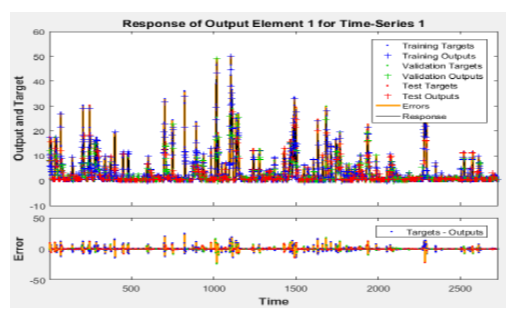

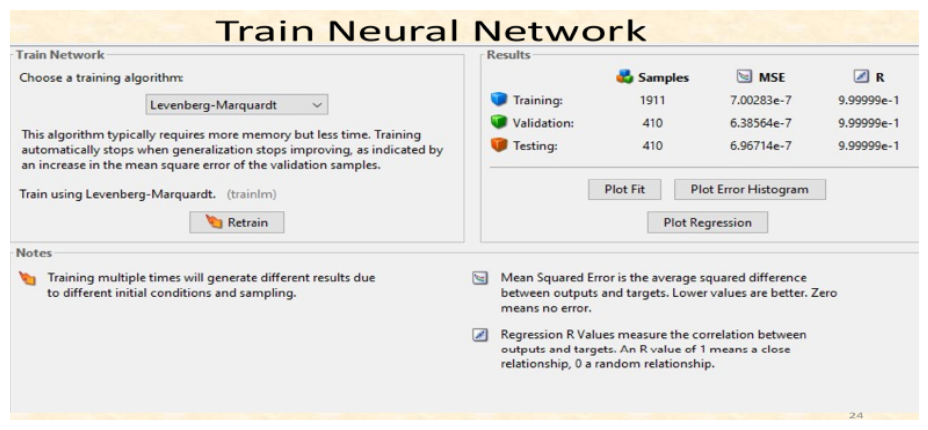

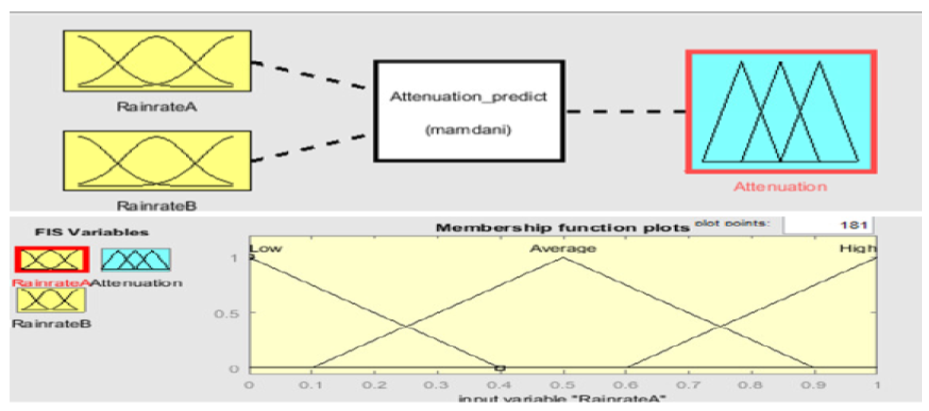

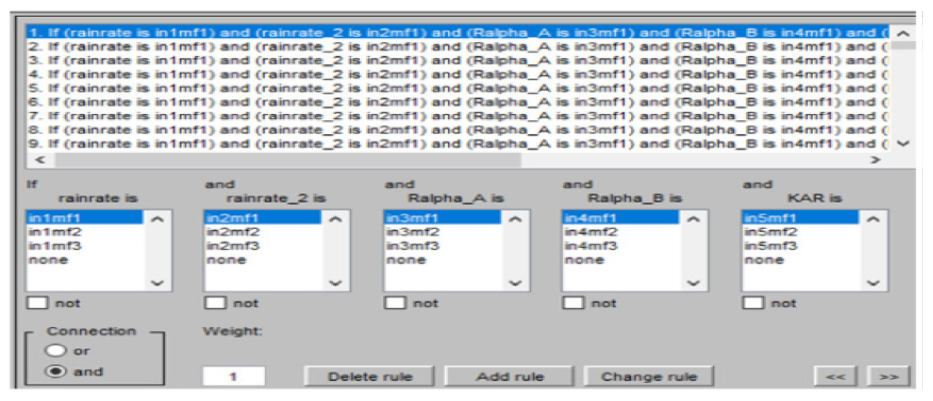

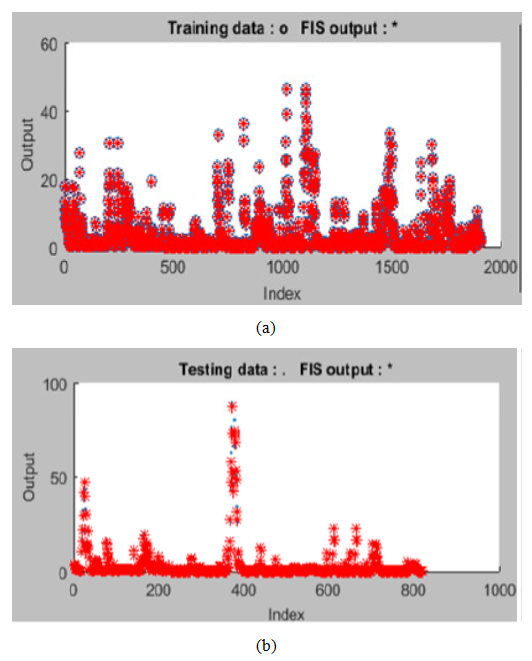

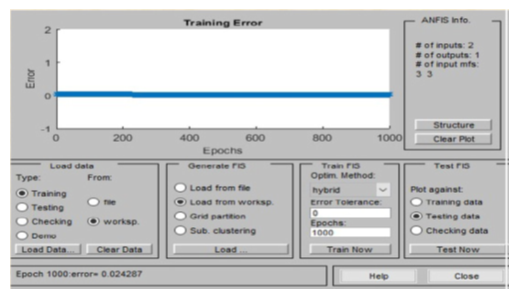

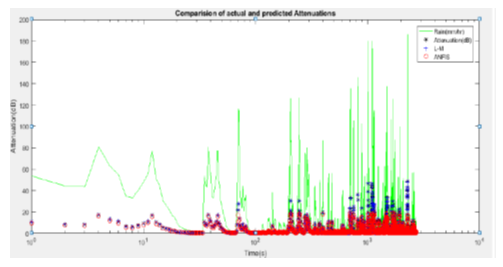

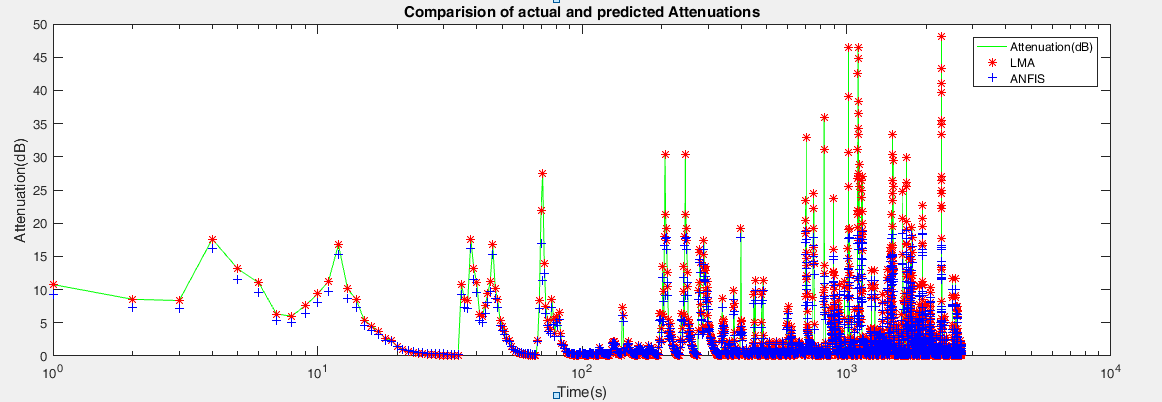

- The MLPNN and the ANFIS were trained using the LMA through simulation studies and the structure of the simulated MLPNN and the ANFIS networks are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8 respectively. The LMA modifies the weight and bias parameters in accordance with LMA optimization scheme. In Figures 9 and 10, the Levenberg-Marquardt optimization procedure determines the update of the parameters using the adaptation parameter (Mu). Figure 6 displays the gradient and Mu-values of the trained network. Mu is the control parameter for the neural network training technique; its initial value was 0.001, and its maximum value is 1e10.

| Figure 7. Structure of the simulated feedforward multilayer perceptron neural network (MLPNN) |

| Figure 8. Structure of the simulated ANFIS network |

| Figure 9. The graphical user interface (GUI) for the MLPNN training |

| Figure 10. Convergence parameters for MLPNN training after 179 iterations |

| Figure 11. Convergence results for training, validation, testing based on mean squares error (MSE) |

| Figure 12. Linear regression ® fitting result for the MLPNN training |

| Figure 13. The MLPNN QoS output predictions and the prediction errors |

| Figure 14. Performance metrics of the trained neural network |

| Figure 15. Inputs, rule editor, output and membership function editor of the ANFIS network |

| Figure 16. Automatically generated fuzzy rules by the trained ANFIS |

| Figure 17. The ANFIS output predictions: (a) training data and (b) test data |

| Figure 18. Training errors for the ANFIS network at 1000 iterations |

|

| Figure 19. Comparison of actual rain rate, attenuation, and predicted attenuation |

| Figure 20. Comparison of actual rain rate, attenuation, and predicted attenuation |

| Figure 21. Logarithmic comparison of actual and predicted attenuation |

6. Conclusions and Future Direction

6.1. Conclusions

- Five-year rainfall data has been utilized in this study to assess various prediction methods and suggest mitigating strategies to enhance service quality and control signal to noise. Comparing the ANFIS and our actual output attenuation revealed an overall percentage difference of 0.2517%, whereas the Levenberg-Marquardt neural network and our actual output attenuation revealed a difference of 0.0234%. This suggests that, despite the fact that both MLPNN and ANFIS are beneficial for prediction purposes, attenuation prediction in neural networks is more accurate and suitable. This is corroborated in the results for both MLPNN and ANFIS, which exhibit the same pattern- and graphic-based trend. It was then deduced that the MLPNN result shows a more accurate and reliable prediction with lesser error and thus is a good decision support system for mitigating rain attenuation. With the predicted values, our model can accurately manage the loss of signal (attenuation) and provide necessary mitigation techniques for an effective signal to maintain quality of service, especially under intense weather conditions.

6.2. Future Direction

- Future research should expand the scope of this study by incorporating longer-term and more diverse meteorological datasets to improve the robustness of attenuation prediction models. Extending rainfall data beyond five years, and integrating additional climatic variables such as temperature, humidity, cloud density, and wind speed, could further enhance model generalization under varying environmental conditions.Furthermore, hybrid deep-learning architectures such as deep convolutional neural networks (Deep CNN), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, random forest, support vector machine (SVM), and deep neuro-fuzzy systems should be investigated to determine their potential to outperform conventional MLPNN and ANFIS models in highly random weather scenarios. Future studies may also examine real-time adaptive learning techniques, enabling models to update continuously as new rainfall and attenuation data become available, thus improving accuracy during dangerous weather conditions.Another promising direction is the development of intelligent, automated mitigation frameworks that combine predictive outputs with proactive countermeasures. These may include dynamic power control, adaptive modulation and coding, site diversity, and antenna beam optimization, triggered autonomously based on predicted attenuation levels. Implementing such systems within real communication networks will allow for end-to-end performance assessment and validation.Finally, integrating satellite-based rainfall measurement data, IoT-enabled weather sensors, and GIS-based spatial analysis can support the creation of more broad attenuation maps. These tools will provide network designers and operators with better insights for infrastructure design, resilience planning, and long-term service quality improvement.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML