-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Networks and Communications

p-ISSN: 2168-4936 e-ISSN: 2168-4944

2019; 9(1): 23-36

doi:10.5923/j.ijnc.20190901.02

Configurable Beam-Steering Network for Phase Array Antennas- Part I: Proposed Configurable Photonic True Time Delay Line

Duaa Alyas Karim Aljaf1, Raad Sami Fyath2

1Department of Electronic and Communications Engineering, Al-Nahrain University, Baghdad, Iraq

2Department of Computer Engineering, Al-Nahrain University, Baghdad, Iraq

Correspondence to: Duaa Alyas Karim Aljaf, Department of Electronic and Communications Engineering, Al-Nahrain University, Baghdad, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Beam-steering networks for phase array antennas (PAAs) have been successfully and efficiently implemented in the literature using photonic true time delay line (TTDL). The delay line has been designed according to the operating microwave frequency  and number of radiating elements N of the PAA and cannot be adopted efficiently for other PAAs operating at different parameters values. Future wireless communication base stations will deal with PAAs having different values of

and number of radiating elements N of the PAA and cannot be adopted efficiently for other PAAs operating at different parameters values. Future wireless communication base stations will deal with PAAs having different values of  and N and therefore, it is essential to design smart beam-steering networks. In this paper, a configurable photonic TTDL is proposed for PAA beam-steering network. The delay line consists of cascaded linearly chirped fiber Bragg gratings (LCFBGs) whose number is adopted according to the operating frequency, number of radiating elements, and steering angle. A parametric study of the used LCFBG is performed and the simulation results reveal that a FBG designed with 80 mm length and modified Gaussian apodization offers a 562 ps time delay difference across its reflectively spectrum bandwidth (4 nm). The scanning capabilities of PAAs incorporating this configurable photonic delay line is investigated and the results are given in the accompanying paper [1]. The simulation results reported here are obtained using OptiGrating ver. 14-1 Software.

and N and therefore, it is essential to design smart beam-steering networks. In this paper, a configurable photonic TTDL is proposed for PAA beam-steering network. The delay line consists of cascaded linearly chirped fiber Bragg gratings (LCFBGs) whose number is adopted according to the operating frequency, number of radiating elements, and steering angle. A parametric study of the used LCFBG is performed and the simulation results reveal that a FBG designed with 80 mm length and modified Gaussian apodization offers a 562 ps time delay difference across its reflectively spectrum bandwidth (4 nm). The scanning capabilities of PAAs incorporating this configurable photonic delay line is investigated and the results are given in the accompanying paper [1]. The simulation results reported here are obtained using OptiGrating ver. 14-1 Software.

Keywords: Phase array antenna, Linearly chirped fiber Bragg grating, Microwave photonics, True time delay line

Cite this paper: Duaa Alyas Karim Aljaf, Raad Sami Fyath, Configurable Beam-Steering Network for Phase Array Antennas- Part I: Proposed Configurable Photonic True Time Delay Line, International Journal of Networks and Communications, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 23-36. doi: 10.5923/j.ijnc.20190901.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

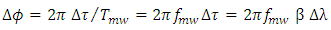

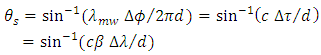

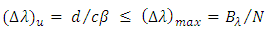

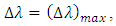

- Recently, there is increasing interest in microwave photonics (MWP)-based signal processing which connects microwave domain with optical domain [2, 3]. The MWP technique enables efficient generation and processing of microwave signals using photonic technology [4, 5]. The main inherent features of MWP are immunity to electromagnetic interference, low loss, wide-bandwidth operation, compactness, and light weight [6, 7]. Further, MWP can offer tunability and reconfigurability for the whole system, which is hard to realize using conventional microwave technologies [8, 9].One of the main applications of MWP is beam steering and beam forming of microwave and millimeter wave phase array antennas (PAAs) [10, 5]. This application has been demonstrated successfully for wireless communications [11-13] and radar imaging systems [14]. The steering operation of traditional PAAs relies on microwave phase shifters which are used to control the phase of each radiating elements (sub-antenna) in the PAA. The interference of electromagnetic waves from these radiating elements control the beam pattern in the free space. Microwave photonic phase shifters suffer from beam-squint problem which limits the operation bandwidth [5]. This problem arises due to the dependence of beam steering angle on the microwave frequency which leads to the divergence of beam directions of different microwave frequencies at increasing steering angles. This problem can be solved by using a true time delay line (TTDL) which offers a linear phase shift-frequency characteristics and hence ensures a frequency-independent steering angle. Photonic delay line has been emerged as promising candidates for TTDL beam steering networks in terms of loss and bandwidth beside its suitability for implementation in MWP platform [15, 16]. In photonic beam steering network, the microwave signal is mapped into an optical carrier. The modulated optical carrier is then launched into the photonic TTDL to get the required delay and the resultant optical signal is photodetector to get a delayed version of the microwave signal.It is worth to mention here that photonic-based beam steering networks cannot be in general realized using conventional photonic transmission lines (optical fibers or optical waveguides). These photonic lines offer time delay which is almost independent of the laser wavelength. The time delay

offered by photonic line of length

offered by photonic line of length  is given by

is given by  , where

, where  is the speed of light in free space and

is the speed of light in free space and  is the refractive index of propagation medium. Therefore, the phase shift

is the refractive index of propagation medium. Therefore, the phase shift  between successive radiating elements cannot be varied by tuning the laser wavelength. In contrasts photonic TTDL implemented using fiber Brag grating (FBG) technology offers a time delay

between successive radiating elements cannot be varied by tuning the laser wavelength. In contrasts photonic TTDL implemented using fiber Brag grating (FBG) technology offers a time delay  which is a function of the laser wavelength

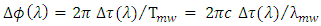

which is a function of the laser wavelength  [6]. The corresponding phase shift

[6]. The corresponding phase shift  where

where  is the time period of a microwave signal of frequency

is the time period of a microwave signal of frequency  (or wavelength

(or wavelength  ). Hence the steering angle

). Hence the steering angle  [17] becomes equal to

[17] becomes equal to  , where

, where  is the radiating elements spacing. In this case

is the radiating elements spacing. In this case  is independent of the microwave signal spectral contents and can be controlled by tuning the laser wavelength

is independent of the microwave signal spectral contents and can be controlled by tuning the laser wavelength  The individual radiating element are frequently space about a half–wavelength apart (i.e.,

The individual radiating element are frequently space about a half–wavelength apart (i.e.,  ), where

), where  is taken as the center wavelength of the microwave signal spectrum. This makes

is taken as the center wavelength of the microwave signal spectrum. This makes

Therefore, to obtain a fixed value of

Therefore, to obtain a fixed value of  the time delay

the time delay  should be adapted according to the operating microwave frequency

should be adapted according to the operating microwave frequency  At low microwave frequencies, the required value of

At low microwave frequencies, the required value of  can not be obtained by one FBG and cascaded configuration of photonic TTDLs is required. This issue is addressed in this paper where an adaptive photonic TTDL is proposed using FBGAs and optical switches. The concepts of this work may be applied in base stations of wireless communication systems which will deal with PAAs having different values of

can not be obtained by one FBG and cascaded configuration of photonic TTDLs is required. This issue is addressed in this paper where an adaptive photonic TTDL is proposed using FBGAs and optical switches. The concepts of this work may be applied in base stations of wireless communication systems which will deal with PAAs having different values of  and number of radiating elements. Therefore, it is essential to design smart beam-steering networks for these base stations and this subject will be addressed in the accompanying paper [1].

and number of radiating elements. Therefore, it is essential to design smart beam-steering networks for these base stations and this subject will be addressed in the accompanying paper [1].2. Background on Apodized Linearly Chirped Fiber Bragg Grating

- This section introduces the main concepts of FBG and its linearly chirped version. The principles of refractive index-apodization profiles are briefly illustrated.

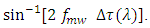

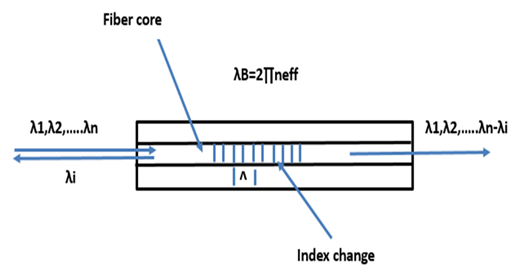

2.1. Concepts of Fiber Bragg Grating

- Fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs) are formed by constructing a periodic or aquasi-periodic modulation of refractive index inside the core of an optical fiber, see Figure 1. This change in index of refraction is typically created by exposing the fiber core to an intense interference pattern of UV energy. The exposure produces a permanent increase in the refractive index of the fiber's core, creating a fixed index modulation according to the exposure pattern. This fixed index modulation is called a grating [18]. A small amount of light is reflected at each period. All the reflected light signals combine coherently to one large reflection at a particular wavelength. This is referred to as the Bragg condition, and the wavelength at which this reflection occurs is called the Bragg wavelength. Only those wavelengths that satisfy the Bragg condition are affected and strongly back reflected through the same core of the fiber. Uniform FBGs are based on a periodical modulation of the refractive index in the core of an optical fiber Figure 1, and they are the most popular grating-based type of technology.

| Figure 1. Concept of fiber Bragg grating. Illustrative spectra of the incident, reflected and transmitted waves are given |

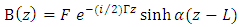

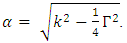

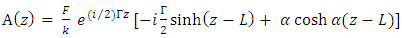

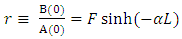

equals to [19]

equals to [19] | (1) |

is the period of the refractive index modulation, and

is the period of the refractive index modulation, and  is the effective refractive index of the fiber core. In a chirped FBG, periodicity of the modulation is not constant, but it changes along the propagation axis z; the function

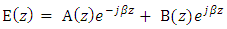

is the effective refractive index of the fiber core. In a chirped FBG, periodicity of the modulation is not constant, but it changes along the propagation axis z; the function  defines the chirp pattern. This implies that each different section of the grating reflects a different Bragg wavelength, and the overall spectrum of the FBG results from the spectrum of each section of the grating.Consider an uniform FBG extended along the z-axis from z=0 to z=L. Assume that the periodic variation of the refractive index over the grating axial direction (z–axis) takes the following form [20]

defines the chirp pattern. This implies that each different section of the grating reflects a different Bragg wavelength, and the overall spectrum of the FBG results from the spectrum of each section of the grating.Consider an uniform FBG extended along the z-axis from z=0 to z=L. Assume that the periodic variation of the refractive index over the grating axial direction (z–axis) takes the following form [20] | (2) |

is the axial average of the refractive index,

is the axial average of the refractive index,  represents the peak of the refractive index variation, and

represents the peak of the refractive index variation, and  denotes the grating pitch which represents the period of the z-dependent refractive index variation as shown in Figure 2. The typical value of

denotes the grating pitch which represents the period of the z-dependent refractive index variation as shown in Figure 2. The typical value of  varies in the range

varies in the range  to

to  . Under weak coupling (i.e.,

. Under weak coupling (i.e.,  , the fundamental mode of the grating wavelength can be expressed as [18]

, the fundamental mode of the grating wavelength can be expressed as [18] | Figure 2. Refractive index change in optical fiber |

| (3) |

and

and  represent forward- and backward-propagating modes, respectively, and

represent forward- and backward-propagating modes, respectively, and  is the propagation constant

is the propagation constant  | (4) |

is the effective refractive index of the fundamental mode whose wavelength is

is the effective refractive index of the fundamental mode whose wavelength is  The relation between the forward mode

The relation between the forward mode  and the backward mode

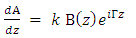

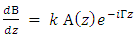

and the backward mode  is governed by the following coupled equations [18]

is governed by the following coupled equations [18] | (5a) |

| (5b) |

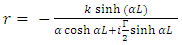

is the coupling coefficient

is the coupling coefficient  | (5c) |

| (5d) |

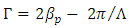

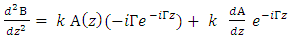

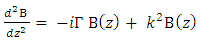

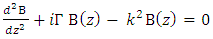

and

and  . Taking the derivative of both sided of equ. 3 with respect to z yields

. Taking the derivative of both sided of equ. 3 with respect to z yields  | (6a) |

| (6b) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Using equ. 5b yields

Using equ. 5b yields  | (9) |

gives

gives | (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

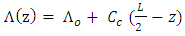

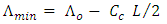

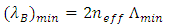

2.2. Linearly Chirped FBG

- The chirped FBG has nonuniform grating period

along its length z. When

along its length z. When  varies linearly with z, the structure is called linearly chirped (LC) FBG. The LCFBG is characterized by a wider reflection spectrum since each wavelength component is reflected at different grating position. This type of FBG can be fabricated by varying the peak refractive index variation

varies linearly with z, the structure is called linearly chirped (LC) FBG. The LCFBG is characterized by a wider reflection spectrum since each wavelength component is reflected at different grating position. This type of FBG can be fabricated by varying the peak refractive index variation  (see equ. 2) with the axial length z. For an FBG extending from z = 0 to z = L, the linearly chirped period can be expressed as [20]

(see equ. 2) with the axial length z. For an FBG extending from z = 0 to z = L, the linearly chirped period can be expressed as [20] | (13a) |

is the center period of the grating and

is the center period of the grating and  is the chirp parameter. The maximum and minimum grating periods occur at z = 0 and z = L, respectively

is the chirp parameter. The maximum and minimum grating periods occur at z = 0 and z = L, respectively  | (13b) |

| (13c) |

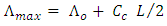

and

and  is the total chirp. Recall that the Bragg wavelength

is the total chirp. Recall that the Bragg wavelength  is related to the grating period

is related to the grating period  and effective refractive index

and effective refractive index  by

by  Then for a LCFBG, the minimum and maximum value of the Bragg wavelength can be computed from

Then for a LCFBG, the minimum and maximum value of the Bragg wavelength can be computed from  | (14) |

| (15) |

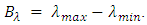

of the FBG is defined as the variation of the time delay

of the FBG is defined as the variation of the time delay  associated with reflection transfer function with wavelength

associated with reflection transfer function with wavelength  | (16) |

| (17) |

which corresponds to the grating period at the axial center of the FBG. Note that

which corresponds to the grating period at the axial center of the FBG. Note that  is constant over the spectral range of interest and this ensures a linear variation of time delay with

is constant over the spectral range of interest and this ensures a linear variation of time delay with  This feature is very important to design TTDL where the time delay can be varied linearly with the laser wavelength.

This feature is very important to design TTDL where the time delay can be varied linearly with the laser wavelength.2.3. Apodization Profiles

- Refractive index-apodization profile refers to the case when the peak of the refractive index variation

is not uniform along the FBG axis (see equ. 2). In this case

is not uniform along the FBG axis (see equ. 2). In this case  is z-dependent and can be expressed as

is z-dependent and can be expressed as | (18) |

corresponds to the uniform apodization profile where the peak of the refractive index is uniform across the length of the FBG and T(z) is the apodization profile or function. Note that T(z) is similar to a spatial window used in signal processing.It is well known from the literature that using apodization and linear chirping in Bragg gratings reduces the side lobe level in the reflectivity response and also the group time delay response ripple [21]. However, different apodization profiles having different impact and it would be useful to choose the profile that is more suitable for the problem under investigation. In this work, the apodization profile is chosen to give large time delay difference across the LCFBG spectrum. The investigation done in this work reveals that the best results are obtained by using two types of apodization profiles(i) Modified Gaussian Apodization (MGA) [22]

corresponds to the uniform apodization profile where the peak of the refractive index is uniform across the length of the FBG and T(z) is the apodization profile or function. Note that T(z) is similar to a spatial window used in signal processing.It is well known from the literature that using apodization and linear chirping in Bragg gratings reduces the side lobe level in the reflectivity response and also the group time delay response ripple [21]. However, different apodization profiles having different impact and it would be useful to choose the profile that is more suitable for the problem under investigation. In this work, the apodization profile is chosen to give large time delay difference across the LCFBG spectrum. The investigation done in this work reveals that the best results are obtained by using two types of apodization profiles(i) Modified Gaussian Apodization (MGA) [22] | (19) |

is the taper parameter.(ii) Gaussian Apodization (GA) [22]

is the taper parameter.(ii) Gaussian Apodization (GA) [22] | (20) |

3. Proposed Beam-steering Network

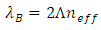

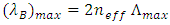

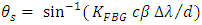

3.1. System Configuration

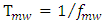

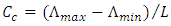

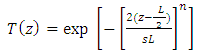

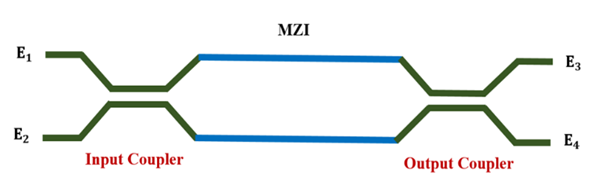

- Figure 3 illustrates the main concepts of the configurable photonic TTDL-based beam-steering network investigated in this work. For N-element PAA, the outputs of N-tunable semiconductor lasers (TSLs) are multiplexed and the resultant waveform is then modulated by the microwave signal. The modulated multiplexed signal is launched into the configurable TTDL and the output is applied to 1:N demultiplexer. Each of the demultiplexer output is detected by a photodiode (PD) to recover a delayed version of the microwave signal which is then amplified by a low-noise amplifier (LNA) before feeding the radiating element. The configurable photonic delay line consists of K cascaded identical FBGs. Successive FBGs are separated by electrically controlled optical switch (OS) (see Figure 3(b-d)). The OS operates in either bar state or cross state depending whether the state of the control signal is ON or OFF, respectively. When the OS operates in the bar state, the switch passes the input optical signal to next FBG for extra delay. In the cross state, the input signal does not need extra time delay and therefore passes directly to the demultiplexer input.

| Figure 3. Proposed photonic TTDL-based beam steering. (a) System configuration; (b) Configurable photonic delay line; (c) Subsystem A; (d) Subsystem B |

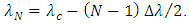

3.2. Design Guidelines

- The performance of the photonic TTDL depends mainly on the reflection characteristics of the employed FBGs. The design of the FBG should satisfy the following requirements(i) High-peak and wideband optical power reflection spectrum centered at a given wavelength

The wavelength of the used TSLs should distributed around the center wavelength

The wavelength of the used TSLs should distributed around the center wavelength  and see almost the same power reflection. According to that, -0.5dB bandwidth measure is used here to estimate the bandwidth of the power reflection spectrum

and see almost the same power reflection. According to that, -0.5dB bandwidth measure is used here to estimate the bandwidth of the power reflection spectrum  This ensures 0dB (i.e., 100%) power reflection at the center wavelengths

This ensures 0dB (i.e., 100%) power reflection at the center wavelengths  and -0.5dB (i.e., 89%) at the lower and higher cutoff wavelengths. The slight variations in the power reflections seen by the semiconductor lasers can be equalized at the receiver end by adapting the gains of the LNAs.(ii) Linear variation of the time delay associated with FBG amplitude (field) reflection transfer function across the spectrum and without ripple. This is useful to ensure a linear variation of the time delay with TSLs wavelength spacing.(iii) Large time delay across the spectrum

and -0.5dB (i.e., 89%) at the lower and higher cutoff wavelengths. The slight variations in the power reflections seen by the semiconductor lasers can be equalized at the receiver end by adapting the gains of the LNAs.(ii) Linear variation of the time delay associated with FBG amplitude (field) reflection transfer function across the spectrum and without ripple. This is useful to ensure a linear variation of the time delay with TSLs wavelength spacing.(iii) Large time delay across the spectrum  and it is preferred to yield high dispersion parameter

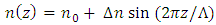

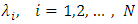

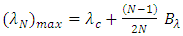

and it is preferred to yield high dispersion parameter  A linearly chirped FBG (LCFBG) is used in this delay line to yield a linear time delay-wavelength characteristics. The Bragg wavelength varies linearly along the FBG axis and yields a time delay that decreases linearly with the wavelength in the reflection spectrum bandwidth. Figure 4 shows an ideal time delay characteristics

A linearly chirped FBG (LCFBG) is used in this delay line to yield a linear time delay-wavelength characteristics. The Bragg wavelength varies linearly along the FBG axis and yields a time delay that decreases linearly with the wavelength in the reflection spectrum bandwidth. Figure 4 shows an ideal time delay characteristics  of a LCFBG across the power reflection bandwidth

of a LCFBG across the power reflection bandwidth  Here

Here  and

and  are, respectively, the upper and low cutoff wavelengths of the spectrum. The chirp parameter of the FBG is a positive quantity and computed from

are, respectively, the upper and low cutoff wavelengths of the spectrum. The chirp parameter of the FBG is a positive quantity and computed from | (21) |

| Figure 4. Time delay characteristics  of a LCFBG across the power reflection bandwidth of a LCFBG across the power reflection bandwidth |

within the reflection bandwidth can be expressed as

within the reflection bandwidth can be expressed as | (22) |

and

and  are the time delays associated with

are the time delays associated with  and the reference wavelength

and the reference wavelength  , respectively.The time delay difference between two adjacent TSLs whose wavelengths differs by

, respectively.The time delay difference between two adjacent TSLs whose wavelengths differs by  is given by

is given by | (23) |

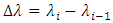

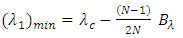

with

with  The TSLs operate in continuous-wave (CW) mode with equal wavelength spacing

The TSLs operate in continuous-wave (CW) mode with equal wavelength spacing  The wavelengths of the TSLs (

The wavelengths of the TSLs ( ) are assumed to be distributed symmetrically around the spectrum center wavelength. Figure 5 illustrates the wavelengths corresponding to a 4-element PAA.

) are assumed to be distributed symmetrically around the spectrum center wavelength. Figure 5 illustrates the wavelengths corresponding to a 4-element PAA. | Figure 5. Wavelengths distribution of four TSLs used in the 4-element of PAA |

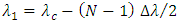

| (24) |

and

and  The maximum wavelength spacing

The maximum wavelength spacing  is set to

is set to  to ensure that the wavelengths of the first and last lasers (i.e.,

to ensure that the wavelengths of the first and last lasers (i.e.,  and

and  ) are not located at the spectrum edges. According to that

) are not located at the spectrum edges. According to that  and

and  even when

even when  approaches it maximum value. Setting

approaches it maximum value. Setting  to

to  is useful to tolerate FBG fabrication error. In other words, this setting ensures that the wavelengths of the TSLs are laying within the FBG spectrum. When

is useful to tolerate FBG fabrication error. In other words, this setting ensures that the wavelengths of the TSLs are laying within the FBG spectrum. When  tends to its maximum value

tends to its maximum value  then

then  and

and  approach their minimum and maximum values, respectively.

approach their minimum and maximum values, respectively. | (25a) |

| (25b) |

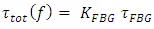

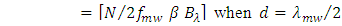

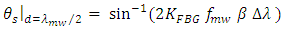

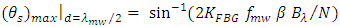

with its beam-steering network uses a single LCFBG. The phase shift

with its beam-steering network uses a single LCFBG. The phase shift  between two successive radiating elements is related to the corresponding time delay difference by

between two successive radiating elements is related to the corresponding time delay difference by  | (26) |

and

and  is the period and frequency of the microwave signal used to modulate the lasers optical carriers, respectively. Then the steering angle

is the period and frequency of the microwave signal used to modulate the lasers optical carriers, respectively. Then the steering angle  is given by

is given by  | (27) |

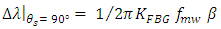

function should not exceed 1. This yields the following threshold condition which determines the upper bound of the wavelength spacing,

function should not exceed 1. This yields the following threshold condition which determines the upper bound of the wavelength spacing,

| (28) |

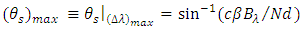

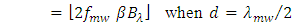

then the maximum achievable steering angle is given by

then the maximum achievable steering angle is given by  | (29) |

| (30a) |

| (30b) |

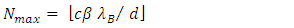

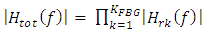

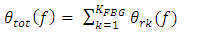

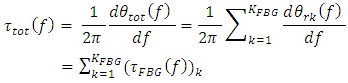

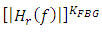

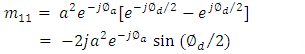

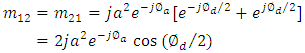

denotes the maximum integer in the argument.b- Multi FBG-Based Beam-Steering NetworkConsider the case when the beam steering is achieved by using number of FBGs,

denotes the maximum integer in the argument.b- Multi FBG-Based Beam-Steering NetworkConsider the case when the beam steering is achieved by using number of FBGs,  from the K cascaded FBG available in the photonic line. The used optical circulators isolate the incident field from the reflected field for each used FBG. Therefore, the isolator acts as a buffer stage between two successive FBGs. Hence the total reflection transfer function of the

from the K cascaded FBG available in the photonic line. The used optical circulators isolate the incident field from the reflected field for each used FBG. Therefore, the isolator acts as a buffer stage between two successive FBGs. Hence the total reflection transfer function of the  cascaded gratings can be computed as the product of the transfer functions of

cascaded gratings can be computed as the product of the transfer functions of  gratings. The word “isolated” is used here to identify that the reflected field of the FBG does not affect the operation of the previous FBG in the cascaded network. According to this discussion, the total reflection transfer function of the

gratings. The word “isolated” is used here to identify that the reflected field of the FBG does not affect the operation of the previous FBG in the cascaded network. According to this discussion, the total reflection transfer function of the  cascaded gratings can be expressed as

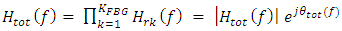

cascaded gratings can be expressed as | (31a) |

is the field reflection transfer function of the

is the field reflection transfer function of the  FBG involves in the operation and

FBG involves in the operation and  is the optical frequency. Further, the magnitude and the phase of the total field reflection transfer function are expressed, respectively as

is the optical frequency. Further, the magnitude and the phase of the total field reflection transfer function are expressed, respectively as | (31b) |

| (31c) |

seen by used cascaded FBGs is computed as

seen by used cascaded FBGs is computed as | (32) |

represents the time delay associated with the reflection transfer function of the

represents the time delay associated with the reflection transfer function of the  FBG evaluated at the optical frequency

FBG evaluated at the optical frequency  Note that(i) The total time delay is the accumulation of the individual time delays of the used FBGs calculated under isolation condition.(ii) When the used FBGs are identical, then

Note that(i) The total time delay is the accumulation of the individual time delays of the used FBGs calculated under isolation condition.(ii) When the used FBGs are identical, then

and

and  where

where  and

and  correspond to a single FBG.(iii) If each FBG is designed to have 100% power reflection at the center frequency and -0.5dB bandwidth consideration, then the total power reflection evaluated at the FBG spectrum edges is 89.%, 79.4%, 70.8%, and 63.1% when

correspond to a single FBG.(iii) If each FBG is designed to have 100% power reflection at the center frequency and -0.5dB bandwidth consideration, then the total power reflection evaluated at the FBG spectrum edges is 89.%, 79.4%, 70.8%, and 63.1% when  = 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, This requires careful consideration to adapt the gains of the LNAs to compensate for the power reflection variation seen by the TSLs.(iv) For identical

= 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, This requires careful consideration to adapt the gains of the LNAs to compensate for the power reflection variation seen by the TSLs.(iv) For identical  gratings, the steering angle becomes

gratings, the steering angle becomes | (33a) |

| (33b) |

| (33c) |

| (33d) |

denotes ceil function which rounds up the argument to the next integer.(v) Using element spacing

denotes ceil function which rounds up the argument to the next integer.(v) Using element spacing  equals

equals  yields

yields | (34a) |

| (34b) |

the required wavelength difference

the required wavelength difference  can be estimated the following expression

can be estimated the following expression  | (35a) |

| (35b) |

Optical SwitchThe

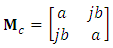

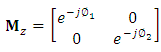

Optical SwitchThe  optical switch can be designed using Mach-Zehnder (MZ) configuration and implemented using silicon photonic platform. Figure 6 shows a schematic of MZ switch which consists of an input optical coupler, interferometric MZ region, and an output optical coupler. The control voltage is applied across one of the MZ arms to change its refractive index and hence introducing propagation phase difference with respect to the other arm [23].

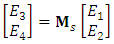

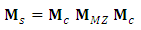

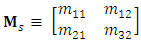

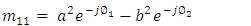

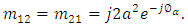

optical switch can be designed using Mach-Zehnder (MZ) configuration and implemented using silicon photonic platform. Figure 6 shows a schematic of MZ switch which consists of an input optical coupler, interferometric MZ region, and an output optical coupler. The control voltage is applied across one of the MZ arms to change its refractive index and hence introducing propagation phase difference with respect to the other arm [23]. | Figure 6. Schematic of the  Mach-Zhender switch used in the proposed photonic delay line Mach-Zhender switch used in the proposed photonic delay line |

| (36) |

and

and  are, respectively, the bar and cross transmission coefficients of the coupler. The MZ interferometer (MZI) is assumed to have lossless arm waveguides and therefore, the transfer matrix

are, respectively, the bar and cross transmission coefficients of the coupler. The MZ interferometer (MZI) is assumed to have lossless arm waveguides and therefore, the transfer matrix  which relates the output fields to the input fields will be determined by the propagation phases of the two arms

which relates the output fields to the input fields will be determined by the propagation phases of the two arms | (37) |

and

and  are, respectively, the phases gained by the electric fields at the end of the upper and lower waveguides.If one assumes identical input and output couplers, the switch output fields

are, respectively, the phases gained by the electric fields at the end of the upper and lower waveguides.If one assumes identical input and output couplers, the switch output fields  and

and  are related to its input fields

are related to its input fields  and

and  by

by | (38a) |

is the transfer function of the

is the transfer function of the  switch

switch  | (38b) |

| (38c) |

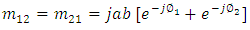

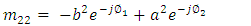

| (39a) |

| (39b) |

| (39c) |

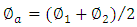

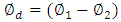

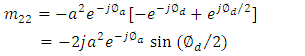

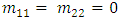

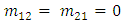

which corresponds to a 3dB-directionl coupler. Introducing

which corresponds to a 3dB-directionl coupler. Introducing  and

and  as the phase average and difference, respectively, leads to

as the phase average and difference, respectively, leads to | (40a) |

| (40b) |

| (40c) |

leads to

leads to  . Recall that

. Recall that  and this is independent of the condition

and this is independent of the condition  . Consider now the following special operating states(i) Case I: No applied voltageIn this case,

. Consider now the following special operating states(i) Case I: No applied voltageIn this case,  (assuming equal-length MZ arms). Then

(assuming equal-length MZ arms). Then  and

and  This corresponds to cross-state operation. Since the optical power is proportional to the absolute-value square if the electric field, then

This corresponds to cross-state operation. Since the optical power is proportional to the absolute-value square if the electric field, then  and

and  (ii) Case II: Voltage is applied to yield

(ii) Case II: Voltage is applied to yield  In this case

In this case  and

and  This indicates bar-state operation which yields

This indicates bar-state operation which yields

and

and  The insertion loss of the switch,

The insertion loss of the switch,  , can be Compared from

, can be Compared from For the two special cases mentioned above,

For the two special cases mentioned above,  . Note that the loss of the directional coupler

. Note that the loss of the directional coupler

and this equals

and this equals  when

when  . For lossless coupler (i.e.,

. For lossless coupler (i.e.,  ) then

) then  . For lossy coupler,

. For lossy coupler,  Note further that

Note further that  since the MZ waveguide arms are assumed lossless.

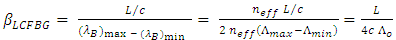

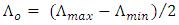

since the MZ waveguide arms are assumed lossless.4. Performance Evaluation of Linearly Chirped FBG

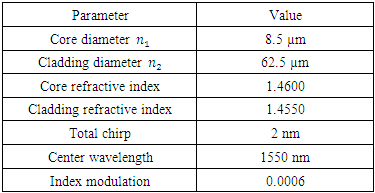

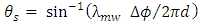

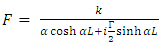

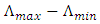

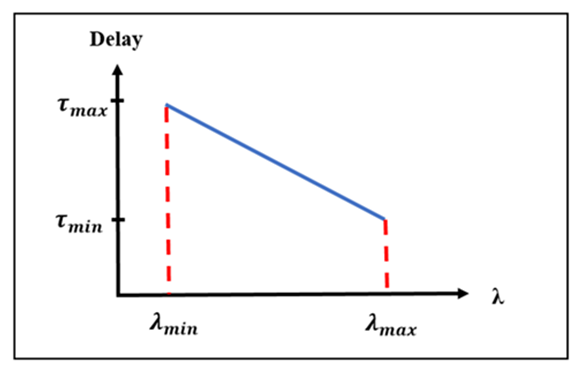

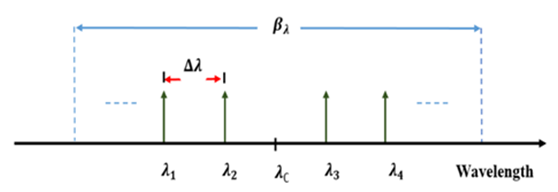

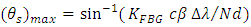

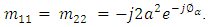

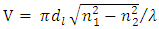

- The time delay-wavelength characteristics of the proposed photonic delay line dependents on the reflection response of the used LCFBG. This section presents parametric study to characterize the time delay spectrum associated with the reflection transfer function of LCFBG operating with apodization profile and 1550 nm reference wavelength. The simulation results are obtained using the commercial software package "OptiGrating ver. 14-1". Initial simulation tests are performed to select the apodization profile suitable for efficient design of photonic.TTDL-based beam steering. The target is to get(i) Large time delay difference across the FBG spectrum bandwidth (which is denoted here by

).(ii) The time delay

).(ii) The time delay  varies linearly across the spectrum bandwidth without ripple.The initial simulation tests performed in this work have shown that modified Gaussian apodization (MGA) designed with, n = 4 and s = 0.7 offers the best time delay spectrum performance. The next apodization profile to be used is the Gaussian (GA) designed with s = 0.5. Therefore, the investigation in this section focuses only on these two apodization types. In the following, results are reported for MGZ-based FBG. Results related to Gaussian profile are given in the Appendix.The FBG structure parameters used in the simulation are chosen to match those of a standard single-mode fiber (SSMF), see Table 1. This is useful to achieve high coupling efficiency at the FBG / SSMF interface. The

varies linearly across the spectrum bandwidth without ripple.The initial simulation tests performed in this work have shown that modified Gaussian apodization (MGA) designed with, n = 4 and s = 0.7 offers the best time delay spectrum performance. The next apodization profile to be used is the Gaussian (GA) designed with s = 0.5. Therefore, the investigation in this section focuses only on these two apodization types. In the following, results are reported for MGZ-based FBG. Results related to Gaussian profile are given in the Appendix.The FBG structure parameters used in the simulation are chosen to match those of a standard single-mode fiber (SSMF), see Table 1. This is useful to achieve high coupling efficiency at the FBG / SSMF interface. The  of the FBG is estimated to be 2.24 at

of the FBG is estimated to be 2.24 at  nm using the expression

nm using the expression  [32]. Here

[32]. Here  is the core diameter,

is the core diameter,  is the core refractive index, and

is the core refractive index, and  is the cladding refractive index. Note that

is the cladding refractive index. Note that  is lower than 2.405 which is the upper bound for single-mode operation. Unless otherwise started, the following parameters are used in the simulation: refractive index modulation

is lower than 2.405 which is the upper bound for single-mode operation. Unless otherwise started, the following parameters are used in the simulation: refractive index modulation

total chirp

total chirp  and FBG length L= 80 mm.

and FBG length L= 80 mm.

|

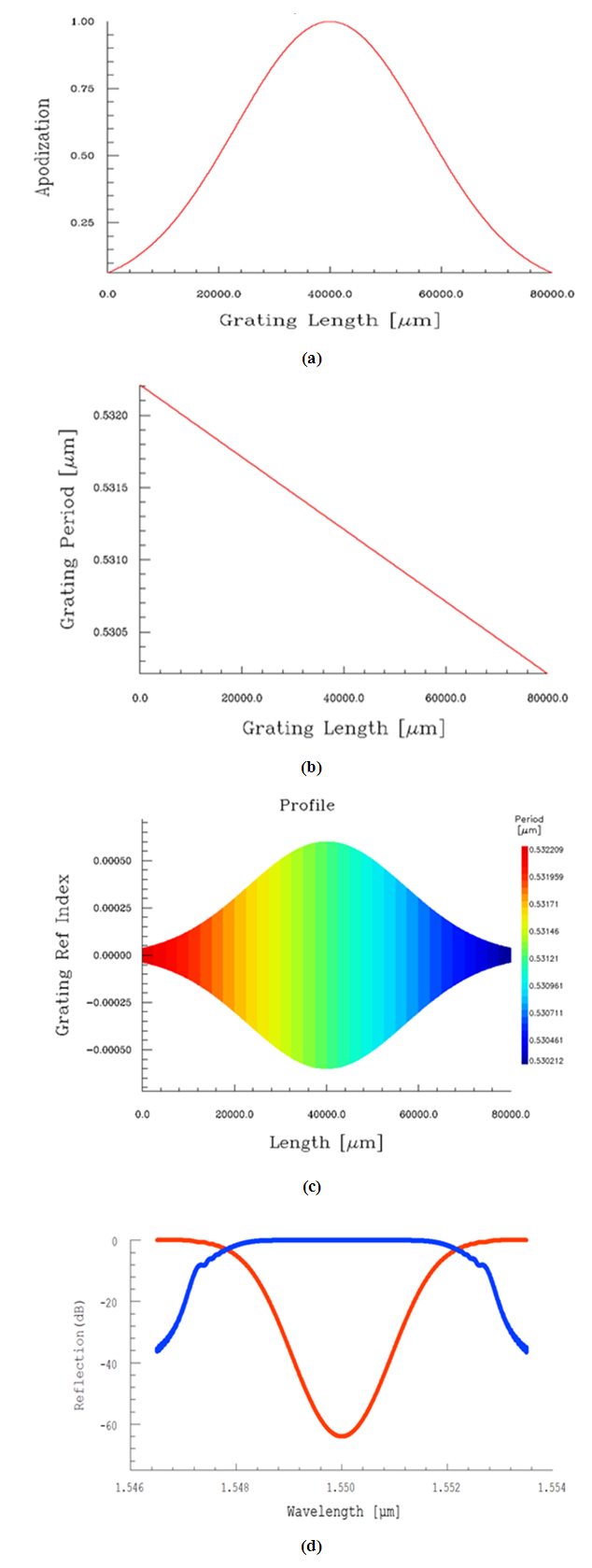

Parts a and b of this figure describe the apodization profile and chirp profile, respectively. The variation of the grating refractive index modulation

Parts a and b of this figure describe the apodization profile and chirp profile, respectively. The variation of the grating refractive index modulation  and grating period

and grating period  along the FBG length is displayed in Figure 7c. Note that the grating period decreases linearly with z (from

along the FBG length is displayed in Figure 7c. Note that the grating period decreases linearly with z (from  nm at z = 0 to

nm at z = 0 to  nm at z = L). The total chirp is

nm at z = L). The total chirp is  and the chirp parameter

and the chirp parameter

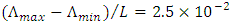

nm/mm. Part d of Figure 7 shows the spectrum of both power reflection and transmission transfer functions. The reflectivity spectrum has a bandwidth

nm/mm. Part d of Figure 7 shows the spectrum of both power reflection and transmission transfer functions. The reflectivity spectrum has a bandwidth  nm at -0.5dB level and 0dB peak level at the center wavelength

nm at -0.5dB level and 0dB peak level at the center wavelength  nm. The variation of the time delay across the reflectivity spectrum is presented in Figure 7e which shows a linear decrease with wavelength. The maximum time delay difference

nm. The variation of the time delay across the reflectivity spectrum is presented in Figure 7e which shows a linear decrease with wavelength. The maximum time delay difference  ps which yields a dispersion parameter

ps which yields a dispersion parameter  ps/nm.

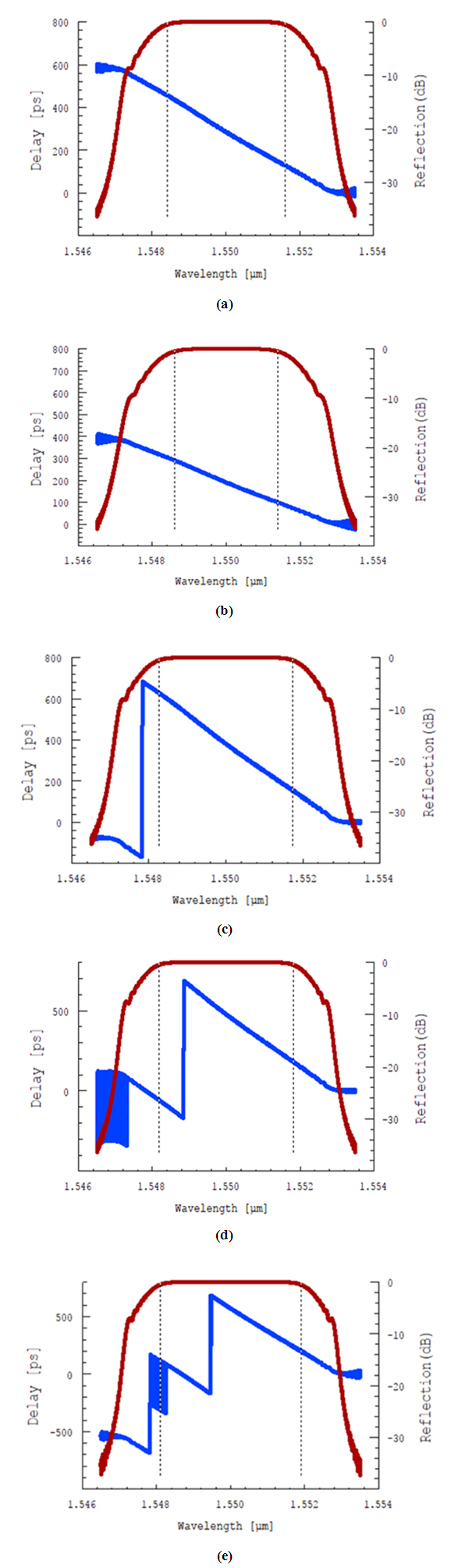

ps/nm. and

and  ps over the reflectivity bandwidth

ps over the reflectivity bandwidth  and

and  respectively. The corresponding dispersion parameters

respectively. The corresponding dispersion parameters  are 69, 103.85 and 138.11 ps/nm, respectively.(ii) Increasing L to 100 and 120 nm destroys the linear

are 69, 103.85 and 138.11 ps/nm, respectively.(ii) Increasing L to 100 and 120 nm destroys the linear  characteristics and leads to two and three sections, respectively.

characteristics and leads to two and three sections, respectively. | Figure 8. Effect of FBG length on its power reflectivity and time delay spectrum (a) L= 40 mm (b) L= 60 mm (c) L= 80 mm (d) L= 100 mm (e) L= 120 mm.  Delay Delay  Reflection Reflection |

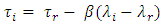

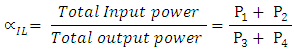

and

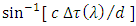

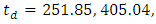

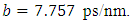

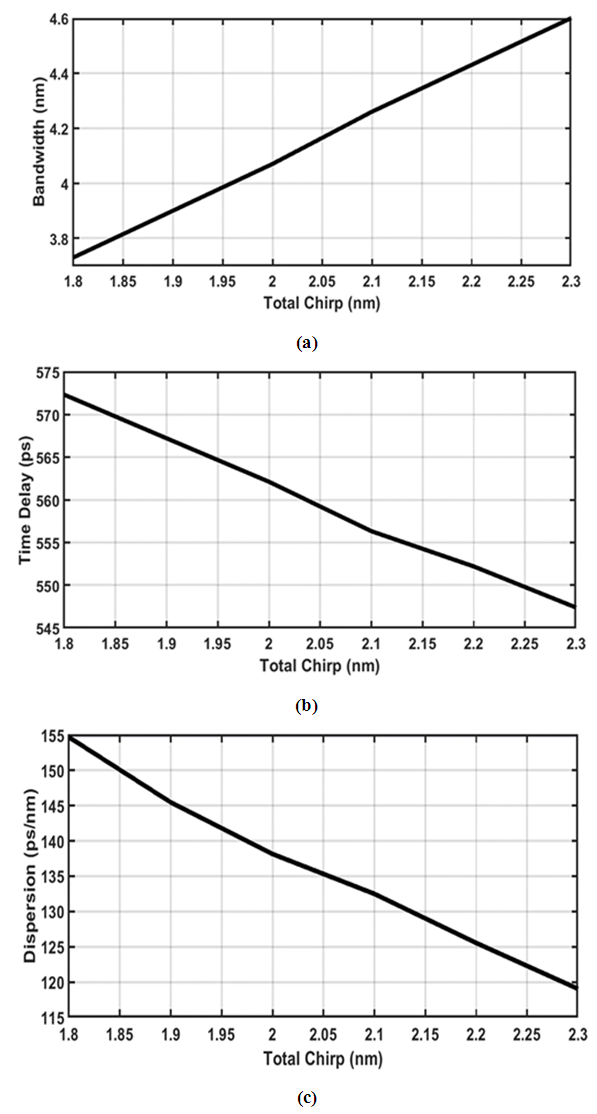

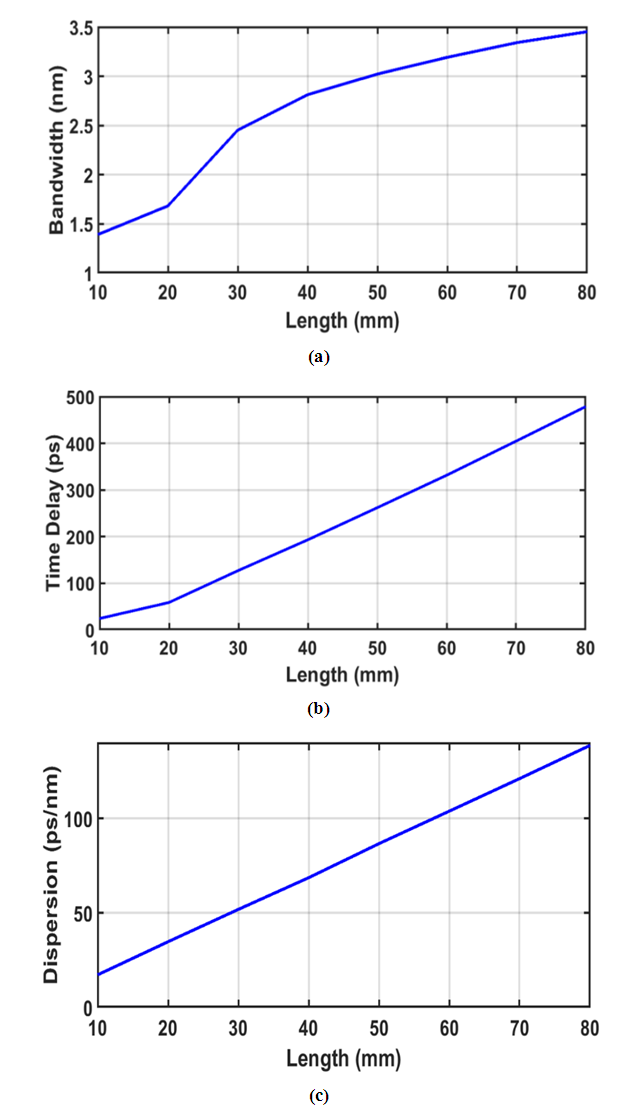

and  on FBG length is illustrated in Figures 9(a-c), respectively. At L = 95 nm, the

on FBG length is illustrated in Figures 9(a-c), respectively. At L = 95 nm, the  characteristics becomes discontinuous and consists of two linear sections. The discontinuous multisession behavior remains for L

characteristics becomes discontinuous and consists of two linear sections. The discontinuous multisession behavior remains for L  95 nm. Therefore, the results in Figure 9 are presented for L

95 nm. Therefore, the results in Figure 9 are presented for L  90 mm. Note that spectrum bandwidth increases sublinearly with FBG length. In contrast, the parameter

90 mm. Note that spectrum bandwidth increases sublinearly with FBG length. In contrast, the parameter  increases almost linearly with L and reaches a maximum value of 562.12 ps at L

increases almost linearly with L and reaches a maximum value of 562.12 ps at L  80 mm. Then

80 mm. Then  decreases with L as L increases toward 90 mm. In the region of L

decreases with L as L increases toward 90 mm. In the region of L  80 mm, the

80 mm, the  relation can be fitted by the linear characteristics

relation can be fitted by the linear characteristics  where

where  and L are measured in ps and mm, respectively. Further,

and L are measured in ps and mm, respectively. Further,  ps and

ps and  In other words,

In other words,  increases by about 7.8 ps for each 1 mm increase in the FBG length when L

increases by about 7.8 ps for each 1 mm increase in the FBG length when L  80 mm. Note further that the sublinear and linear variations of

80 mm. Note further that the sublinear and linear variations of  and

and  respectively, with L (for L

respectively, with L (for L  80 mm region) makes the dispersion parameter

80 mm region) makes the dispersion parameter  an increasing function of L here. At L

an increasing function of L here. At L  80 mm,

80 mm,  approaches its maximum value of 562.12ps and

approaches its maximum value of 562.12ps and  equals 4.07 nm. This leads to

equals 4.07 nm. This leads to  ps/nm which represents the maximum dispersion parameter in the region of L

ps/nm which represents the maximum dispersion parameter in the region of L  80mm. Therefore, 80 mm-LCFBGs will be used later to design the beam-steering network. It is worth to mention here that the peak power reflectivity

80mm. Therefore, 80 mm-LCFBGs will be used later to design the beam-steering network. It is worth to mention here that the peak power reflectivity  equals

equals  (85%)

(85%)  (98%), and 0dB (100%) at L

(98%), and 0dB (100%) at L  10, 20, and

10, 20, and  30 mm, respectively.

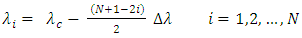

30 mm, respectively. | Figure 9. Effect of FBG length on the (a) bandwidth (b) time delay (c) dispersion |

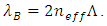

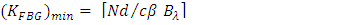

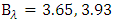

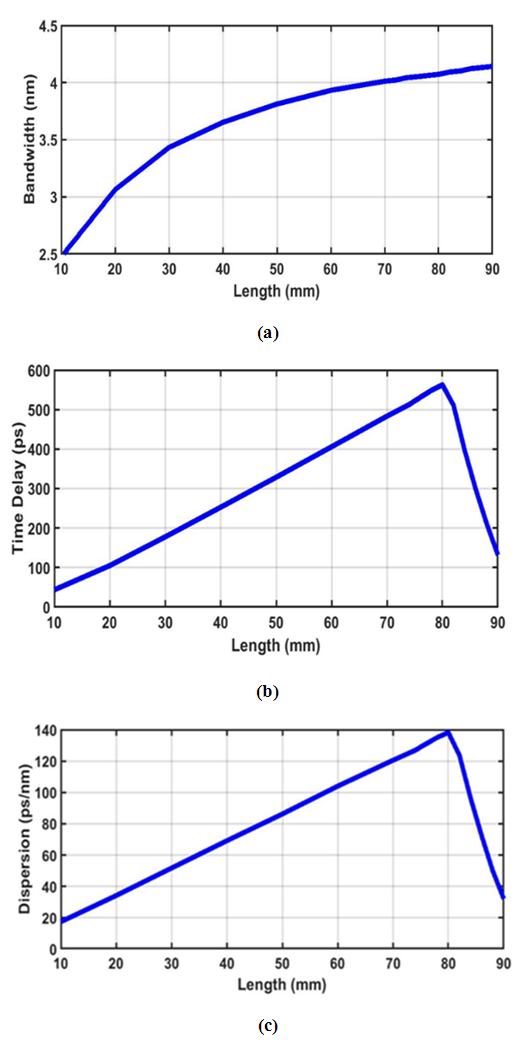

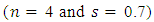

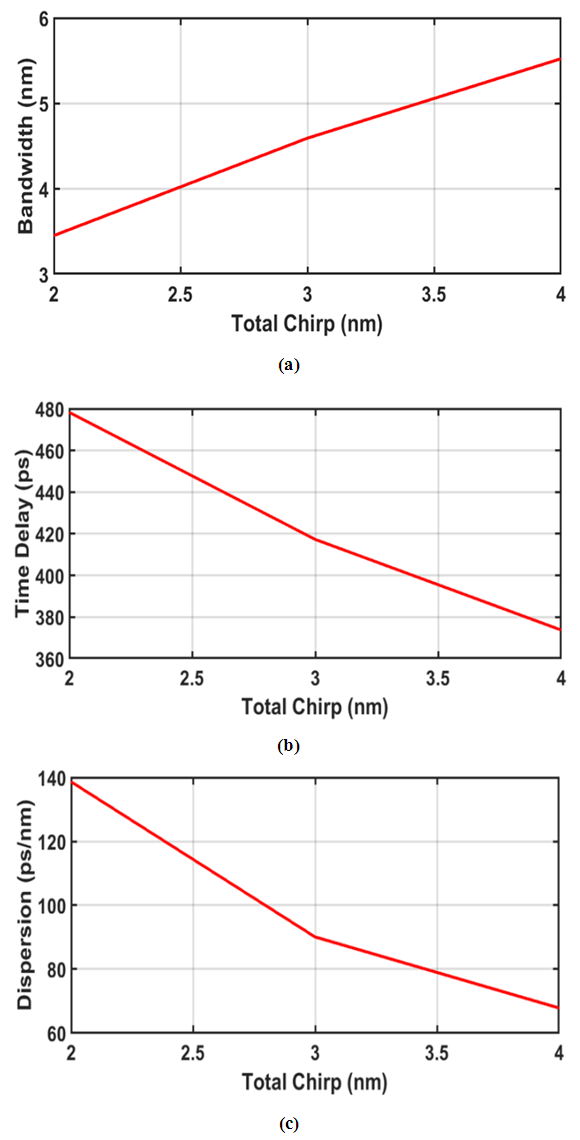

increases linearly with the total chirp (slope

increases linearly with the total chirp (slope  1.74).(ii) The time delay difference

1.74).(ii) The time delay difference  decreases slightly and almost linearly with the total chirp (slope

decreases slightly and almost linearly with the total chirp (slope  -50 ps/nm).(iii) The dispersion parameter decreases almost linearly with total chirp (slope

-50 ps/nm).(iii) The dispersion parameter decreases almost linearly with total chirp (slope  -71 ps/nm).

-71 ps/nm). | Figure 10. Effective of total chirp of 80 mm-LFBG on the (a) bandwidth. (b) time delay. (c) dispersion |

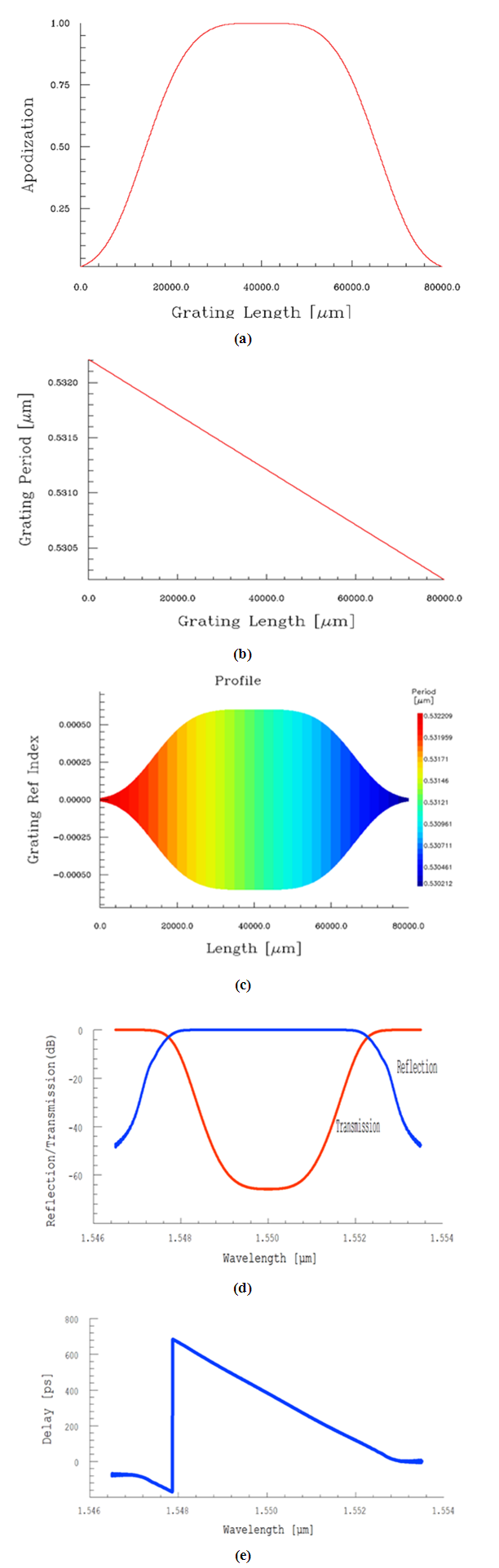

is used as a trade off between the two mentioned performance parameters,

is used as a trade off between the two mentioned performance parameters,  and

and  Table 2 lists performance comparison between two LCFBGs, one is designed with MGA

Table 2 lists performance comparison between two LCFBGs, one is designed with MGA  and the other is designed with GA

and the other is designed with GA  The comparison results are presented for three FBG lengths (40, 60 and 80 mm). Other structure parameters used in the simulation are identical for both FBGs as given in Table 1. The simulation reveals that the peak power reflectivity is 0dB for all the cases considered here and therefore not listed in Table 2. Investigation the results in Table 2 highlights the following findings. Using MGA enhances both spectrum bandwidth

The comparison results are presented for three FBG lengths (40, 60 and 80 mm). Other structure parameters used in the simulation are identical for both FBGs as given in Table 1. The simulation reveals that the peak power reflectivity is 0dB for all the cases considered here and therefore not listed in Table 2. Investigation the results in Table 2 highlights the following findings. Using MGA enhances both spectrum bandwidth  and time delay

and time delay  almost by the same factor over GA. This leads to approximately the same dispersion parameter

almost by the same factor over GA. This leads to approximately the same dispersion parameter  for the two apodization profiles. This enhancement factor is about 1.30, 1.22, and 1.18 for L = 40, 60, and 80 mm, respectively. From engineering point of view, one can say that MGA offers about 20-30% increase in both

for the two apodization profiles. This enhancement factor is about 1.30, 1.22, and 1.18 for L = 40, 60, and 80 mm, respectively. From engineering point of view, one can say that MGA offers about 20-30% increase in both  and

and  over GA and this leads to the same dispersion parameter

over GA and this leads to the same dispersion parameter

|

5. Conclusions

- A Configurable photonic true time delay line (TTDL) consisting of cascaded linearly chirped fiber Bragg grating (LCFBGs) has been proposed to support the design of PAA beam-steering networks. Parametric study of the designed LCFBG has been performed and the simulation results reveal that designing the LCFBG with modified Gaussian apodization (MGA) offers high-performance time delay characteristics. A LCFBG of 80mm length offers 562.12 ps time delay difference across the 4.07 nm spectrum spectral bandwidth. The length of the LCFBG should be chosen carefully to yield a linear time delay-optical wavelength characteristics. Designing the LCFBG with L>80 mm will destroys this linear relation.

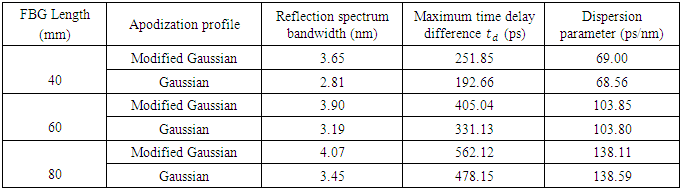

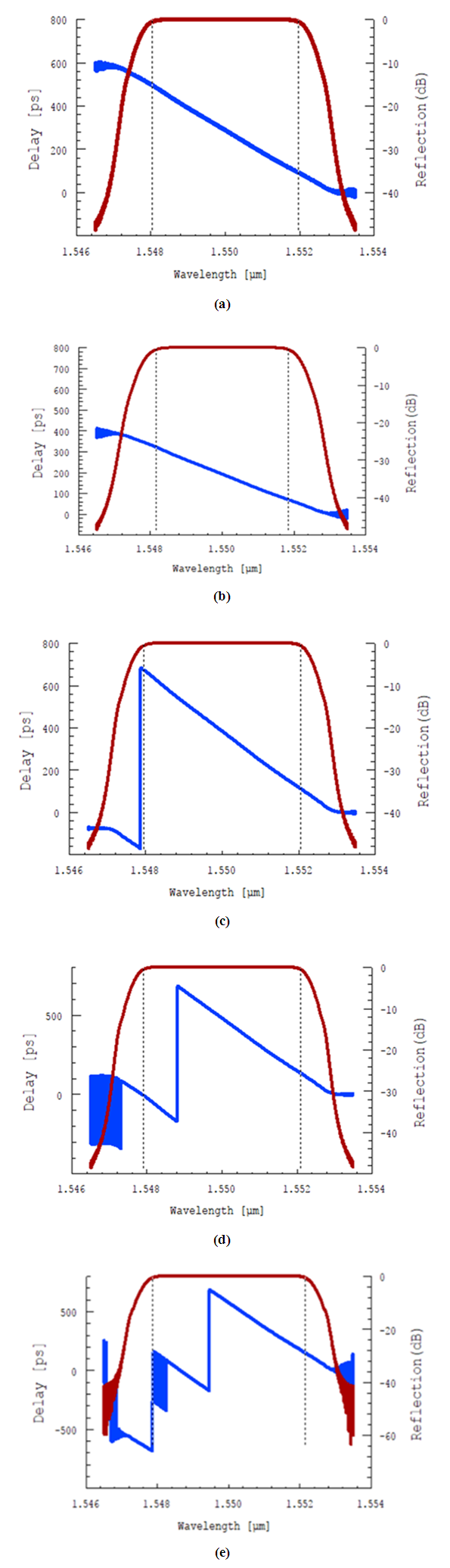

Appendix Performance Parameters of LCFBG Design with Gaussian Apodization

| Figure A1. Characteristics of 80 mm-LCFBG. (a) Apodization profile. (b) Chirp profile. (c) Grating profile. (d) Spectrum of both power reflection and transmission transfer functions |

| Figure A2. Effect of FBG length on its power reflectivity and time delay spectra (a) L= 40 mm (b) L= 60 mm (c) L= 80 mm (d) L= 100 mm (e) L= 120 mm.  Delay Delay  Reflection Reflection |

| Figure A3. Effect of FBG Length on the (a) bandwidth (b) time delay and (c) dispersion |

| Figure A4. Effective of total chirp of 80 mm-LFBG on the (a) bandwidth (b) time delay and (c) dispersion |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML