-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Networks and Communications

p-ISSN: 2168-4936 e-ISSN: 2168-4944

2017; 7(3): 47-54

doi:10.5923/j.ijnc.20170703.01

Trustworthy Communications in Online Brand Communities: Don’t Lie about My Brands, or else!

Greg Clare

Department of Design, Housing and Merchandising, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, U.S.A.

Correspondence to: Greg Clare, Department of Design, Housing and Merchandising, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, U.S.A..

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study measured the impact of consumer communication behaviors in a proposed online brand community for a college convenience store chain and found that deceptive communication practices by community members negatively influenced loyalty but not the perceived value of the brand. Trustworthy member communications in the brand community strongly influenced brand attachment and involvement. Loyalty moderated brand attachment and involvement. Perceived value moderated involvement, but not brand attachment. The study suggests that mechanisms to minimize deceptive communications in an online brand community are recommended.

Keywords: Online Brand Community, Loyalty, Perceived Value, Online Communication

Cite this paper: Greg Clare, Trustworthy Communications in Online Brand Communities: Don’t Lie about My Brands, or else!, International Journal of Networks and Communications, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 47-54. doi: 10.5923/j.ijnc.20170703.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The retailer utilized for this study operates stores located on-campus at a large Midwestern university. Senior management of the retailer is concerned about the viability of its core brand name for the future. Increased competition from established leased retail operations on campus and the influx of new businesses near the university campus combined with declining sales and profits in the core brand’s stores highlight the need for new strategy. Since Internet usage is ubiquitous on the campus by both students and faculty who use numerous communication devices such as office PCs, laptops, tablets and smartphones to communicate, an online brand community facilitating loyal customer communications may help to strengthen the college brand’s image. Two branding strategies are currently under consideration. The first strategy involves retaining the current brand name and using it unilaterally on the campus at both the convenience store operations and all associated residence hall dining facilities. The second, involves retaining the core brand name only within academic building convenience stores while launching alternative branding as part of residence hall cafeterias and convenience store operations. The alternative branding approach will rebrand residence hall facilities with unique restaurant/convenience store names which segment and differentiate the offerings using a neighborhood retailer segmentation approach. To determine whether an online community would benefit both the brand and students, factors influencing the websites use must be better understood prior to making a decision about the optimal branding strategy. Ultimately, management must develop an appropriate business strategy for the campus operations that favorably influences stakeholders brand perceptions, perceived value, brand involvement and attachment to the new online brand community. The established core brand name has a long tradition on the campus and strong brand equity with its customers. In the surrounding community, several convenience store competitors have differentiated themselves from on campus brand by offering competing private label dairy and bakery products, financial services, specialty beverages, lottery ticket sales, and other retail mix variations. The campus convenience operations have similarly differentiated their operations with premium fair trade coffee, prepared meals, healthy snacks, international foods and specialty beverages. The convenience store brand’s embeddedness within the campus buildings provides customers an advantage by offering food items without having to travel to nearby stores off campus. The competing local convenience store competitors do not currently offer an online brand community for their customers. This fact is viewed by management as a potential opportunity to harmonize brand communications while increasing the visibility of the college convenience store brand. On the other hand, management is also concerned that stakeholders will not routinely use such an online community. Support for creation of an online community requires empirical evidence that stakeholders will routinely use the site for brand communications in the absence of increased price promotions and costly website maintenance costs, primarily based on brand interest and loyalty. Numerous Internet communities have demonstrated the power of building brand loyalty with consumers (e.g. Harley Davidson, Inc., Mercedes Benz, Apple Computer, Inc.) through equity oriented online communities. Internet brand communities typically combine both marketing messages, promotions and consumer centric communications. The value of brand communities as sources of business intelligence for marketers may include: customer reviews, personal information linked to brand consumption activities, suggestions from users to improve the brand, public relations communications, transparency, and the ability to create networks of loyal brand supporters, among others. Brand communities sponsored by retailers are inherently social in nature with communications touching on subjects ranging from consumption insights to rich data about the retailer’s products and services through online posting behavior. Consumers brand oriented discussions may contribute to a sense of community supporting pro-social behaviors, brand and service judgments and implications for managerial strategy and decision making. Communications within the online community potentially possess the power to change perceptions of a brand favorably or unfavorably based on management’s use of the data provided.

2. Literature Review

- Brand is a broad term to define retailers and the physical products and services they offer to consumers. The word ‘strength’ is closely tied to brand equity and implies that the stronger a brand is in the minds of customers the greater its value [1]. Brands are sold within markets that are comprised of potential customers with varied degrees of loyalty, purchase frequency, and spending patterns. Brand communities transcend consumers’ brick and mortar store brand experiences by allowing them to learn about and conveniently communicate information about their favorite brands from virtually anywhere via the Internet. Similar to shopping in stores, online community members may interact with people with varied degrees of familiarity and camaraderie while largely remaining anonymous. Due to this fact, communications within brand communities may help build or decrease brand equity quickly through positive brand communications or negative word of mouth effects [2]. The perceived trustworthiness or credibility of information exchanged in online brand communities is critical for dealing with the risks to brand equity. Moderating brand community communications and viewing them as real-time actionable intelligence for improving the brand experience is increasingly important in creating management strategy [3]. Consumers develop brand experiences and form opinions that govern their actions related to those brands, which may in turn influence others brand experiences through network effects. The power of negative word of mouth to decrease a brand’s strength has been demonstrated in past research [4] [5]. Researchers must better understand how online community members perceive the trustworthiness of fellow community members and how the community’s communications influence both their brand experiences and devotion to the brand. The online experience of brands will continue to develop over the next several decades as brand communications occur virtually anywhere on the planet in real-time. The proposed research question that management seeks to better understand is: “What role does deception in brand communications online have on consumers’ loyalty, perceived value (i.e. equity) and attachment to the brand?” Brand marketing communications are critical for influencing brand perceptions, and many researchers routinely examine the factors involved in building loyalty to brands through marketing initiatives. In online brand communities, the impact of member communications and how they are interpreted by other users is a complex topic requiring further research. Factors such as perceptions of a message based on intrinsic or extrinsic brand experience which is then evaluated to supplement prior attributions is one area warranting additional research. In other words, how online brand communications influence judgments over time are not clearly understood, but are serious considerations when attempting to maintain or increase a brand’s perceived equity among consumers [6]. Consumers increasingly influence the brand experience through social network communications, but little is understood about the relationship of member communication effects on brand communities as a whole. From the researcher’s perspective, the impact of how a brand community’s audience judges the trustworthiness of fellow members’ communications may directly influence the perceived value of the website, loyalty to the site and members continuing involvement in communications on the site. Research has demonstrated that a consumer’s knowledge and experience with a company’s brand can influence attitudes toward new products sold by the company [7]. Brand names have been shown to have positive effects on consumers’ perceptions of the brand quality [8]. As consumers become more familiar with brands they become more confident in the brand’s perceived value supporting their purchase decisions. Brand attitudes are favorably influenced by familiarity with the brand [9]. Management at the university retailer desires to keep the core brand front of mind for consumers while introducing differentiated residence hall brands. The management desires to explore the ability of a brand community to fill the gap from decreased locations branded with the core brand name. Internet communities may demonstrate characteristics encountered within geographic communities, particularly with regard to diversity of members and affiliation of groups. According to theory, geographic community members demonstrate what has been labeled as a consciousness of kind [10], relating to a sense of membership within a community in which some members are included and others are excluded by individuals or groups of people. Communication within the community and how others judge those communications may have a relationship to a person’s sense of affiliation with that community. Second, communities are said to periodically engage in rituals and traditions supporting the goals of the community [11], which relate to the meanings that members understand collectively. Community members will typically act to preserve the status quo of communication norms. With regard to brands with which they have substantial experience, they may engage in communications to reduce cognitive dissonance from communications that differ from their personal brand experiences. Similarly, brand community members may advocate for brands in response to communication motivated by the desire for opinion change of members. If consistent brand experiences match a person’s intrinsic or extrinsic motivations, they may wish to ritualize their experiences and express them to others as traditions (e.g. I stop in the coffee shop for a double espresso before work and have done this for years). Moral responsibility [12] relates to the obligations members feel to do what is right represent the brand based on their knowledge and experiences. Motivations of community members may range from imperfect rationalizations of brand performance to altruistic motivations of sharing brand knowledge that potentially influences other people’s adoption or rejection of the brand. Together, these three dimensions of online communities: consciousness of kind, rituals and traditions and moral responsibility form the theory of collective customer empowerment [13]. Researchers have demonstrated that brand communities positively influence loyalty to a brand in their pioneering online brand community exploration. The relevance for retailers of empowering customers to communicate with others about brands may also benefit from increased brand involvement and attachment in addition to perceptions of value and increased loyalty. Involvement is the basis of a consumer’s desire to seek information which enhances knowledge about a brand [14]. Involvement has been demonstrated to influence a customer’s attachment to a brand [15]. If a brand community member demonstrates involvement with a brand, we predict that loyalty and perceived value of the brand moderates trustworthy or deceptive messages within the community. Prior research has found that customers with low brand involvement showed decreased loyalty to the brand [16]. Moderating factors of involvement may include the consumer’s trust for information as credible and represented the members of the community offering the information [17].

3. Hypotheses

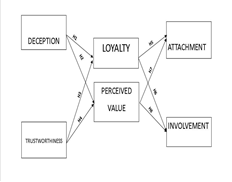

- The proposed model is presented in Figure 1. Consumers seek and share information on the Internet about retailers, often in the form of online reviews and blog posting behaviors. Loyalty relates to repeated involvement with a brand and generally ongoing purchase behavior. The consumer’s goals for sharing information about brands may range from trustworthy to deceptive communications to enhance or attempt to diminish a brand’s reputation. Deceptive communication has been demonstrated to negatively impact loyalty and satisfaction to online retailers [18]. In online brand communities, the effect of deceptive communications by community members is similarly expected to influence brand loyalty negatively. Prior research has demonstrated that user satisfaction with an online community moderates behavioral intentions to use an online brand community and satisfaction influences loyalty to the brand community [19].

| Figure 1. Conceptual Model |

4. Methods

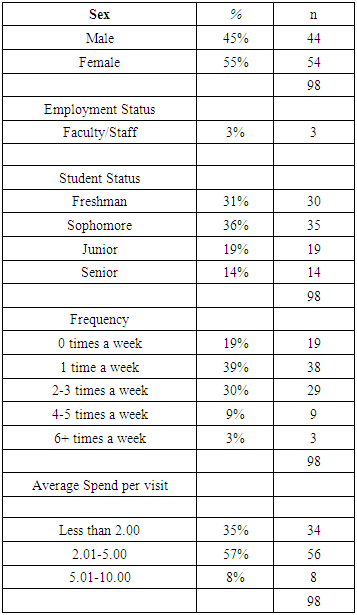

- An online survey of students of a large Midwestern university was conducted through a hosted web domain to test the hypotheses. The survey assessed the impact of a potential online community’s member communication behaviors influence on loyalty, perceived value, brand attachment, and brand involvement. The dependent variable brand involvement is the measure of communicating about the retailer’s core brand and importance to the consumer’s life. A 7-point Likert type scale was used to measure participants’ responses. Involvement, brand attachment, perceived trustworthiness, deception, loyalty and perceived value were adapted from established scales [34]. A convenience sample was collected from college students in a class setting and each student was offered extra credit for completing the survey during a two-week data collection period. No contact information was collected, and survey participants remained completely anonymous. 102 responses were received, and 98 of them were valid, indicating a response rate of 58%. The study was approved by the university’s institutional review board for human subjects research. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

|

5. Results

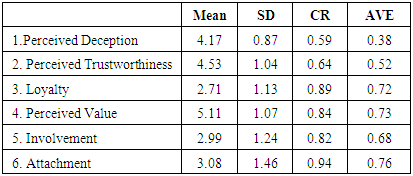

- The relationship of the theorized dimensions was analyzed utilizing a structural equation modeling approach in IBM SPSS and AMOS software, version 21. The measurement and structural model specifications measured the independent and dependent variables and the relationships between those variables. A seven point Likert scale with a neutral midpoint value (4) was used to measure all items. The survey took participants ten to fifteen minutes to complete after clicking the email hyperlink to the survey website and completing online informed consent documentation. Each measure used in the study was tested for internal consistency reliability using the following measures: average inter-item correlation, average item total correlation, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients.Confirmatory Factor Analysis The measurement model was assessed for internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. The alphas for the CFA are presented in Table 2. Convergent validity is demonstrated when each of the measurement items loads with a significant value on its latent construct. Convergent validity was measured by using the standards of loadings over .50 and the average variance extracted (AVE) explained was greater than the average variance unexplained or indicated within measurement error [35]. Discriminant validity, or the measurement of how constructs differ from one another without sharing variance between several constructs, was calculated by comparing the square root of the AVE to the item to construct correlations. Discriminant validity is established when the measurement items show a suitable pattern of loadings based on theoretical assumptions of the assigned factors [36]. Factor loadings less than .7 imply that greater than 50% of the variance in an observed variable is explained by factors different from the construct to which the indicators are theoretically related [37]. The measurement items supported the proposed theoretical constructs.The factor structure of the 27 item post-EFA scale was examined. All but two of the items correlated >.30, indicating factorability. The remaining items were retained for theory purposes. Next, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .83, well above the recommended value of .6. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant X2 = 1389, p<.001. The communalities were all above .5, indicating that each item shared common variance with other items. The anti-image correlation matrix diagonals were all above .5. Given these findings, confirmatory factor analysis was a viable option for the sample. Principal component analysis was used to examine the six factor model: deception, trustworthiness, loyalty, value, attachment, and involvement. The factor structure was examined with direct oblimin rotation, D=0. Initial Eigen values for the factor solution based on the theoretical model explained 71.62% of variance. Five of the six Eigen values explained 66% of the variance with values greater than 1.0. The final factor in the model explained approximately 6% of the variance and was retained for theoretical purposes.

|

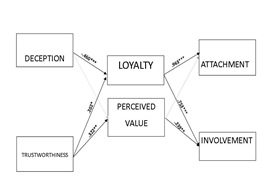

| Figure 2. Path Analysis Diagram |

6. Conclusions and Limitations

- Arguably, in different situations for brand involvement (e.g. online or in stores) influences brand loyalty. Participants had prior experience with the university brand which likely influenced their opinions of a prospective website about the brand. Participant were also likely to evaluate the hypothetical brand community based on their real world experiences online. Participants demonstrated concern about the trustworthiness of communications in the proposed online community. The importance of trustworthy online communications is highlighted in the news media frequently. The question of interest to management was how online communications impact: loyalty, perceived value, brand attachment, and brand involvement. We found evidence that deceptive communications of online community members have a strong negative relationship on loyalty. Trustworthy communications positively impact both loyalty and perceived value. Loyalty has a strong direct relationship on brand attachment and brand involvement. Perceived brand value has a moderate influence on brand involvement. Based on the relationships discovered, management should support trustworthy communications in online communities. Loyalty also produced interactions based on the indirect impact of deceptive communications on both brand attachment and brand involvement. Highly brand loyal customers may experience negative effects on brand attachment and loyalty when they encounter misleading online community communications. This study provides preliminary evidence community moderation may help management influence trustworthy communications through approaches like: censoring messages, content ratings systems, or controlling site membership and access. Additional research is required to determine if management moderation the current model findings. The sample for this study was not randomly selected, and participants received an incentive to participate (i.e. extra credit). There is a risk among participants of self-selection bias not aligned with actual online usage behavior. The sample under-represented the secondary core consumer groups: faculty and graduate students representing only 3% of the total sample n=3. Future studies should seek a more balanced sampling frame. Initial focus groups exploring idiosyncratic differences among campus customers in a mixed method design could support increased generalizability of the findings. The role of customer service at the retailer was not explored in this study, and may be a significant factor in brand loyalty influencing participation in an online community. The impact of word of mouth messages related to the retailer’s brand expressed in cyberspace anonymously may differ from those during real-world store visits or interactions with employees. Surveying consumers about the retailer’s brand or providing an opportunity to complete an online survey at the completion of a transaction in store through random selection at point of sale may help researchers understand how customers’ express opinions differently whether they are in store or online.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML