H P Tiwari1, V K Saxena2, P K Banerjee1, S K Haldar3, R Sharma1, Sanjoy Paul3

1Research and Development Department, Tata Steel Ltd., Jamshedpur, 831007, India

2Chemical Engineering Department, ISM, Dhanbad, 826004, India

3Coke Plant and Hooghly Met Coke (HMC), Tata Steel Ltd., Jamshedpur, 831001, India

Correspondence to: H P Tiwari, Research and Development Department, Tata Steel Ltd., Jamshedpur, 831007, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The coking process is based on the transformation of coal into coke at high temperature. In non-recovery coke oven, heating is usually asymmetric, this may be due to the fact that heating is provided by controlled combustion of volatile matter of charged cake at oven crown and sole flue.In the present investigation, a simplified temperature profiles were simulated to typical temperature profiles of the non-recovery coke oven. The selection criterions of ovens were based on the oven temperature and coking time. Based on measurement of heating pattern, a numerical methodology was proposed for predicting temperature of the intermediate point by using Lagrange interpolation method. Further, a MATLAB-based algorithm was used to predict the same heating pattern based on actual temperature profile in a non-recovery oven. The model was tested and validated with actual temperature profile of six industrial ovens. The model also reproduces the main feature of the measured temperature profile and shown good agreement with experimental data of industrial oven. The predicted temperature profile can discriminate different operating conditions and works well even at low level of temperature deviation. These variations will affect the heating rate and coking cycle, superimposed on the oven crown and sole temperature pattern. However, the operating temperatures were the most important factor for normal operation and found that the heating rate of normal operation was varied in the range of 1.06 -0.62℃/min at a height of 200mm from top & bottom and centre of the charged cake.

Keywords:

Heating Rate, Temperature Profile, Lagrange Interpolation, Non-recovery Coke Oven

Cite this paper:

H P Tiwari, V K Saxena, P K Banerjee, S K Haldar, R Sharma, Sanjoy Paul, "Study on Heating Behaviour of Coal during Carbonization in Non-Recovery Oven", International Journal of Metallurgical Engineering, Vol. 1 No. 6, 2012, pp. 135-142. doi: 10.5923/j.ijmee.20120106.08.

1. Introduction

The coal carbonization is the physico-chemical process, depends on the coking rate, operating parameters, coal blend properties and the transport of thermal energy. The heating rate of coal influences the strength and the fissuring properties of coke. In order to arrive at a homogeneous quality, the heating of the coal cake in a coke oven should therefore be uniform over the total length and height of the oven. In addition to this, the plastic layer migration rate influences the level of thermal stress in the resolidified mass and therefore, the level of fissuring.The strength of coke depends to a large extent on thermal condition prevailing during carbonization. The thermal conditions are influenced by oven crown and sole flue temperature, negative pressure (suction) and carbonization time. The oven temperature and coking time adopted in a normal operation are not independent factors and they vary inversely. At constant temperature, extension of coking time beyond what might appear strictly necessary is known as the ‘soaking time” and allowing the coke to remain in the hot oven during this time is called soaking of coal.In the coking process, the maximum coke temperature is partially decided by the total heat supplied between charging of the coal mass in the oven and discharging the coke. Heating rate is strongly associated with the pattern of heat supply during coke making process. A suitable heat requirement and the pattern of heat supply should be selected from the point of view of coke quality as well as minimizing the total heat consumption.The plastic layer of coal is a highly heterogeneous where intricate physical and chemical equilibria between solid, liquid and gaseous components make the study complex[1]. The formation of a coal plastic layer during coking is a pledge to obtain a coking residue, and the gas pressure arises a layer predetermines a magnitude of coking pressure. The zones, which vary in viscosity[2], in a magnitude of the force to perforate the layer[3], can be separated from the plastic layer. A relatively small amount of the work is connected with the investigation of the “active” role of a coal plastic layer in coking process[4].Softening, devolatilization, swelling and resolidification are closely related. These all mentioned phenomena are highly dependent on the degree of heating rate. It has already beenreported that all coals irrespective of their rank, can be devolatilized without showing any swelling provided the heating rate is sufficiently slow. The carbonization process may be schematically characterized by the following typical equations[5]: | (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

For any part of bulk coal charge, composition of the volatile matter in it is defined in terms of nine species, like, CH4, CO, CO2, C2H6, coal tar, H2, H2O, NH3, H2S.

2.Parameters Influencing Heat Transfer in the Charge

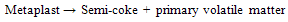

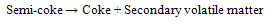

Heat transmission rate to a coal charge in a coke oven is affected by several factors, such as, coal blend, moisture content, bulk density, oven crown and sole temperature, etc. These factors influence the thermal phenomena, the most important ones are shown in Figure 1. | Figure 1. Essential parameters influencing the thermal phenomena |

2.1. The Moisture Content

The moisture contentthroughout the coal charge influences the heating; on the one hand a large amount of heat is required for the evaporation of water and on the other hand thermal effects arise from the condensation of water. In addition, the distribution of moisture largely controls the bulk density distribution within the charge. However, the final temperature of the coke is affected by this to a limited amount.

2.2. The Bulk Density

The bulk density of thecharge is an important factor affecting the operation of an oven, its throughput and coke quality. This parameter has mostly depends on the size distribution of the charge, the addition of moisture and binder to the charge. The bulk density in the chamber controls the local heat demand throughout the coke bed and also,the operation of coke oven and coke quality.

2.3. The Oven Regulation

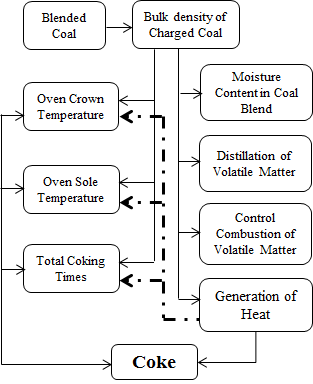

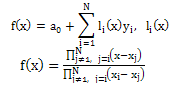

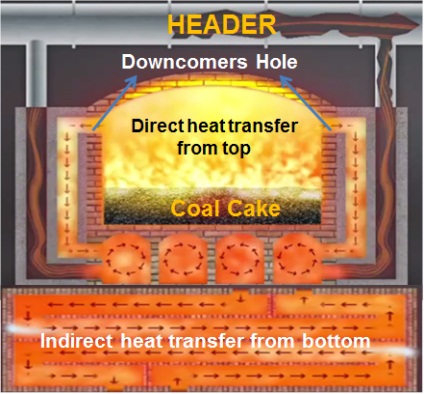

The variation in temperature difference between coking processes in ovens depends largely on the width of the oven. The different heating rates were reported for different oven widths such as, 0.45m and 0.55m for 3.4 and 2.7 K/min, respectively[6].Considerable amounts of work on carbonization in top charge process at high temperature carried out in various countries have revealed that the application of higher coking rate results in improved coke strength and yield. However, the application of higher coking rate in stamp charged coal may give different results since the mechanism of coking is not same as that of top charge. The effects of coal characteristics and carbonization conditions, e.g. bulk density, flue temperatureand moisturecontent on swelling pressure have been studied[7- 8]. Some studies also reported that the heating rate influences the coke quality. Coke Strength after Reaction (CSR) increasesand M40 of coke decreases quite significantly with increase in the heating rate of the coal charge[9]. The operating conditions and heating rates of both recovery and non-recovery coke oven are different due to asymmetry of heating. In recovery coke making, the coal mass is heated at a constant rate with the help of secondary fuel and operate with positive pressure. While the non-recovery oven is operated withnegative pressure, the crude gas produced from the coal in the non-recovery oven is first partially combusted in the free space of oven above the coal charge. This partially combusted crude gas is led through vertical ducts in the side walls (downcomers) into the heating flue system under the oven sole. Here the combustion is completed with further supply of air so that the coal layer is evenly heated from top and bottom[10]. The process control of the non-recovery coke making is accomplished by:○ Monitoring crown and sole flue temperature○ Adjusting sole flue and door induced air ports, and○ Adjusting flue gas uptake dampersIn non-recovery coke oven, it is expected that the heating rate will very with the varying depth of coal cake and temperature of crown & sole flue. Also, it is expected that the heating rate for a particular zone in the chamber will be influenced by the heat transfer among the neighbouring zones and the coking volume of the respective zones. In the present investigation, temperature profiles and heating rates of charged coal cake in different zones in non-recovery coke oven were studied throughout the coking cycle.

3. Mathematical Model

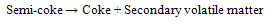

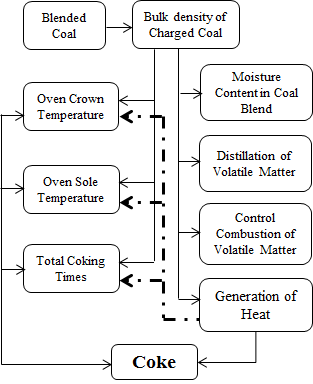

The primary function of the model developed in this study is to make an estimate, for a given coal blend, of the temperature profile at a specified oven crown and sole flue temperature during carbonization in non-recovery oven. In general, heat transfer in the charge is due to a combination of conduction, convection and radiation, as well as heat generated by the reactions and phase change. An equivalent conduction model approach is taken, following Merrick [11-13], where the actual thermal conductivity of the material is replaced by an effective thermal conductivity, which takes into account the effects of conduction and radiation. Different mathematical models are also used for different objectives, such as effect of heating rate, numerical simulation for coal carbonization using PHOENICS, different heat transfer model used in coke oven for predicting heat transfer in coke oven[14-18]. From the literature, it is observed that, most of the works were carried out on recovery coke making and there is less work reported on non-recovery coke making. In the present study,a simplified mathematical model has been developed to predict the temperature profile of non-recovery coke oven. This model assumes transient heat transfer process in one-dimension and is based on fundamental principles of heat transfer, thermodynamics and kinetics of reactions. A statistical correlation was developed with the experimental values. For the implementation of the mathematical models, an in-house interactive MATLAB code named-Lagrange interpolationwas developed to solve the equations of the model numerically to predict the temperature profile. After preliminary processing of the input data for heat recovery oven, the code calculates the intermediate point temperature at different height with respect to time.The code, which calculates the histories of intermediate point temperature, was extended, using the model of temperature profile to calculate the temperature profile of the charge coal cake. The code requires sole flue temperature, crown temperature and temperature profile at five different heights of coal cakeas an inputsand assuming all other parameters were same. The temperature profile of the oven at 50mm distance with an interval of 2.5 hours can be predicted from the model. The description of heat flow from oven free space and sole flue to coal cake from top and bottom of the oven are shown in Figure 2. | Figure 2. Description of heat flow from oven crown& sole flue to coal cake |

3.1. Assumptions of the Model

Several assumptions were made to simplify the case for this study which are as follow: ○ The charge coal cake depth was 1000mm○ Total coking time was 64 hours (normal operation)○ The moisture of coal cake was 9.5±1.5%○ The properties of charged coal cake was constant○ Bulk density of the charge coal cake was constant.○ Indirect heat from bottom (heating at the bottom through 150mm of silica bricks).○ Direct heat from top (heating at the top due to the radiation from temperature).○ Heat transfer in the process was considered in asymmetry condition.

3.2. Methodology

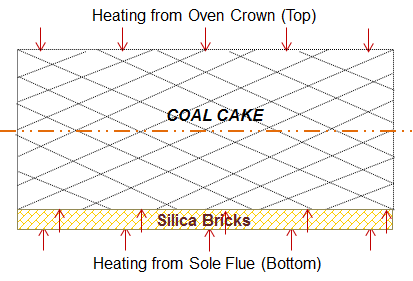

Fourier’s law of heat conduction is applied across first half of the charge assuming symmetry. The following equation is obtained. | (4) |

Where, C is the specific heat capacity of the charge, T is the temperature of the charge, k is the thermal conductivity of the charge, x is the space variable and t is the time variable.The thermal conductivity k can be replaced by an effective thermal conductivity kefor this model.The above equation is a parabolic equation and can be treated as an initial boundary value problem with following boundary conditions.

3.2.1. Initial Condition

| (5) |

3.2.2. Boundary Condition

At the centre | (6) |

At the surface of the charge near to wall; temperature is nearly equal to that of the wall  | (7) |

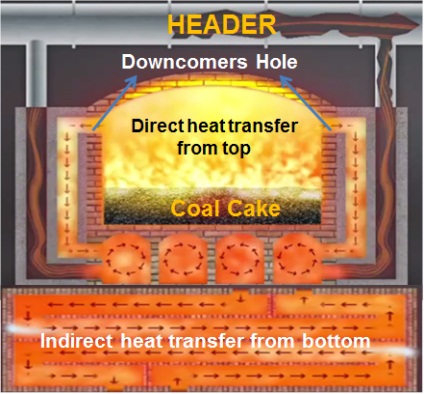

The ke is very difficult to determine, as it varies rigorously with x and t within the oven since the value of C and k is not constant during carbonization. Therefore, mathematical model based on Lagrange extrapolation was chosen to determine temperature histories inside the oven.

3.2.3. Lagrange Extrapolation

| (8) |

Where, xi is the points where the temperature was recorded using thermocouples, yi is the temperature at xi andprediction of temperature is to be made at a distance x.Now, instead of solving the heat equation, the temperature historiesat different thickness of coal cake were predicted by using the equation (8).A MATLAB code was written to solve intermediate temperature curve plot of T vs x for different time (t) intervals.

4. Experimental

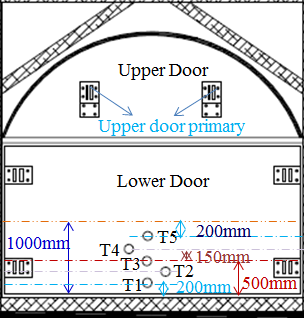

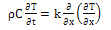

All experimental works were carried out at Hooghly Met Coke (HMC), Tata Steel, India. The temperature profiles of charge coal cake, oven crown and oven sole temperature were recorded with the help of thermocouples throughout the cycle of all experimental oven. The cross-section view of non-recovery coke oven is shown in Figure 3. | Figure 3. Cross-section view of non-recovery coke oven |

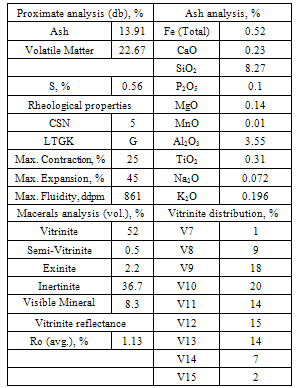

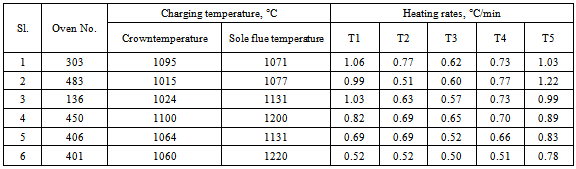

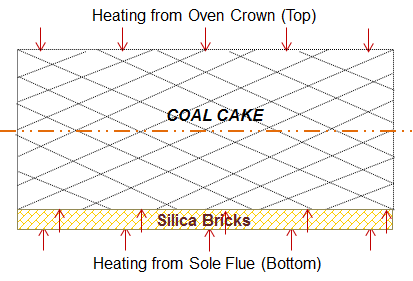

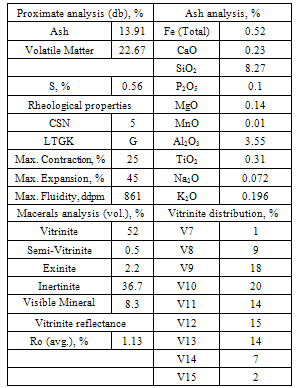

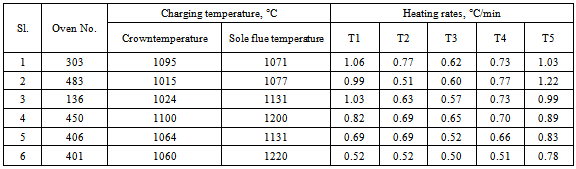

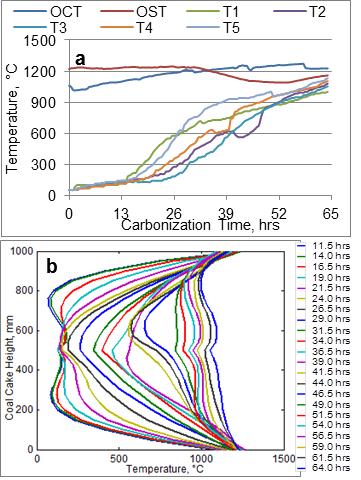

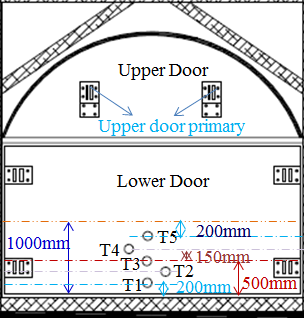

For wider spectrum of study, six different ovens were selected for present study. These ovens were chosen based on oven performance like good, normal and abnormal conditions. In the blend, crushing fineness varies in the range of 89-91% below 3.2 mm size, bulk density varies in the range of 1040-1060 kg/m3 and the moisture was maintained in the range of 9.5-11%in all tests. The properties of charged coal blend, charging temperature of sole flue & oven crown and heating rates of all ovens which are used in this study are shown in Tables1-2. It is a challenging task to conduct such experiments on an operating coke oven facility. In each of the experiments, a set of five thermocouples denoted T1-T5 were inserted directly into the coal charge, to a depth of 1200mm, via holes in the lower oven door for measuring the temperature patterns. Likewise, the sole flue and crown temperature were recorded with the help of thermocouples namely oven sole temperature (OST) and oven crown temperature (OCT) respectively. The thermocouples OST and OCT were inserted at the oven roofand sole fluechannel, and temperature were recorded with an in interval of 30 minutes at all sevenlocations. The locations of all five thermocouples used in experiments are shown in the Figure 4.Table 1. Detail properties of charged coal blend

|

| |

|

Using these temperature profiles, seventeen additional temperature profiles at a particular time were predicted by using Lagrange extrapolation method. For simplification of problems, the charged coal cake is divided into two halves and equations were solved separately in two halves. Now using these data points, the temperature profile of the oven was obtained at different time intervals.Table 2. Charging temperatures and heating rates of experimental ovens

|

| |

|

| Figure 4. Front view of oven and location of thermocouples |

5. Results and Discussions

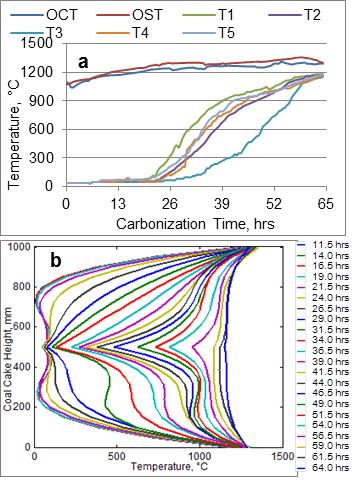

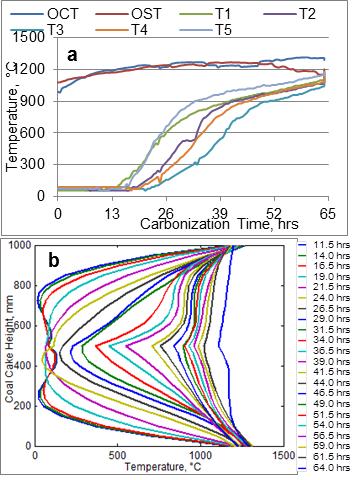

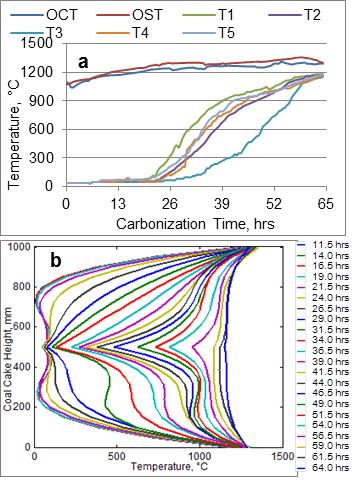

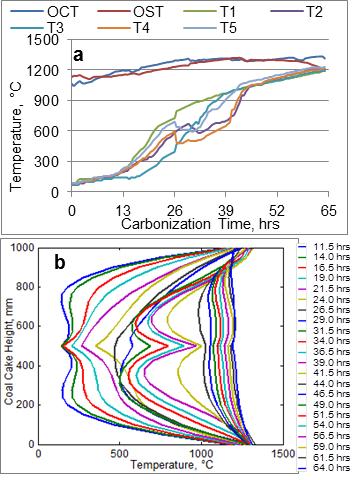

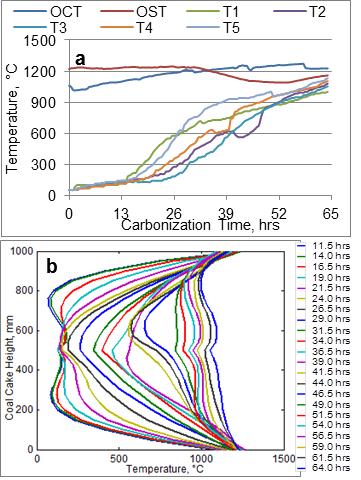

In order to arrive at a homogeneous quality, the heating of the coal cake in the oven should be uniform. The heating rate of coal cake varies widely with varying temperature pattern of oven crown and sole flue throughout the coking cycle. Also, it is expected that the heating rate for a particular zone in the chamber will be influenced by the heat transfer among the neighbouring zones and the coking volume of the respective zones.The maximum heat generation increase somewhat less than linearly with heating rate. As the heating rate is increases, the temperature corresponding to maximum rate is shifted to higher value, but at the same time another side rate of heating decreases and hence uneven carbonization occurs. Therefore, the sole flue temperature is maintained approximately 50℃ higher compare to oven crown temperature because at bottom heat passes through 150mm of silica bricks.Table 2 shows the heating rates of all six ovens which were used in present investigation. Results showed that the heating rates widely varied with varying sole flue and oven crown temperatures. Also, in some cases, the heat penetration rateswere not coinciding at the end of 64 hours coking cycle. This may be due to the difference in heating rate at different height of coal cake (200mm, 350mm and 500mm i.e. centre of charged cake from bottom and top). Experimental and predicted temperature profilesobtained using this model isshown in Figures 5-10. Results show that the predicted temperature profile and experimental temperature profile relationship are in good agreement. It may also be observed from the result that the predicted temperature profile can discriminate between operating conditions and works well even at lower level of temperature deviation (Figures 5b- 10b). These variations will affect the heating rate and coking cycle, superimposed on the oven crown and sole temperature pattern. Therefore, at a lower oven sole and crown temperature, the centre line of charged coal cake is shifted towards the lower temperature zone and the coke pushing is delayed. The rate at which coal charged is heated varies considerably with variations in both crown and sole flue temperatures. The part of the charge near the sole flue and top of cake will be heated at higher rate at early time than at later time, and theserates will be different to those experienced by the part of the charge near the oven centre. Results show that the order of heating rate of all six ovens at different distance of 200mm, 350mm and 500mm from bottom and top varies in the range of 0.60-1.00 & 0.78-1.22, 0.50-0.70 &0.50-0.70 and 0.50-0.60℃/min, respectively. This may be due to the effect of sole flue and crown temperature of oven throughout the cycle. It appears that heating rate measured at different points coincide with the passage of the plastic layers because temperature distribution in different transformation phase is not same. Therefore, the rate of carbonization decreases remarkably towards the centre of the charged coal cake. | Figure 5. Temperature profile of oven no. 303 (a- Actual temperature profile; b- Predicted temperature profile) |

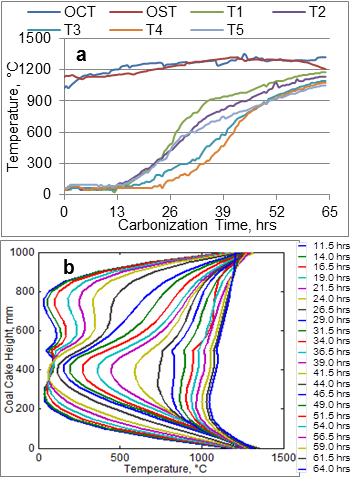

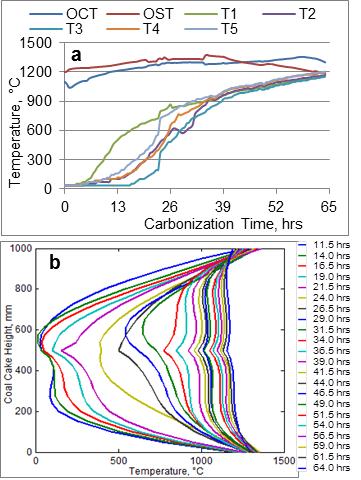

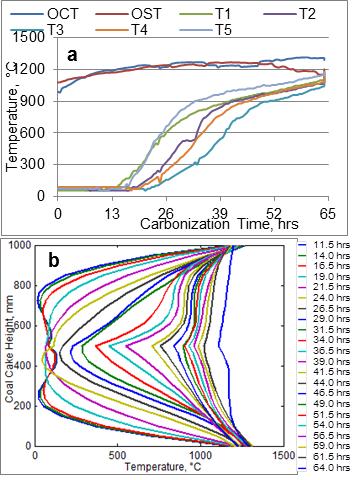

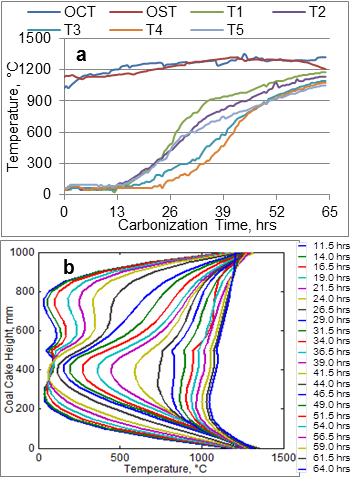

It is evident from results that any deviation from operating range of process variable such as beyond the higher/lower temperature level would affect the performance of oven. The heating rate of oven number 303 at 200mm distance from bottom and top are 1.06 and 1.03℃/min, respectively (Figure 5). Similarly, heating rates at 350mm from the bottom and top are 0.77 and 0.73℃/min and at centre of coal cake i.e. 500mm from top and bottom, the heating rate is 0.62°C/min. It seems that the combustion of hydrocarbons is taking place properly at oven sole and oven crown. It is also observed from Figure 5(b) that the temperature curve from both top and bottom sides are almost uniform.Therefore, during the experiments heat transfer from oven sole and oven crown are linear in oven number 303.The similar heating pattern of oven no. 483 and 136 were also observed (Figures 6-7). Result shows that the heating rate at a point of 200mm from the top (1.22 and 0.99℃/min) is higher compared to 200mm from the bottom (0.99 and 1.03℃/min) of oven no. 483.The temperature of oven crown rose rapidly, as soon as the coal cake was charged in the respective oven. During initial period of heating, the sole flue temperature was higher comparing to oven crown temperature. However, after few hours, the oven sole flue temperature goes down or becomessimilar to oven crown temperature upto approximately 45 hours. This is due to the higher crown temperature of oven no. 483 (Figure 6a). Also, the similar sole flue temperature trend was observed in oven no. 136. This may be due to non-uniform temperature of all five points at the end of 64 hours (Figs. 6a and 7a) of the coking cycle.Figure 8 shows the temperature profile of oven number 450. Results show that the heating rate varies in the range of 0.60 -0.89℃/min. It is also observed that the heating rate at the centre of the charge is almost same as oven nos. 303 and 136 but the heating rate at 200mm and 350mm distance from bottom/top are different. This may due to the uneven temperature during carbonization. Figures 8 (a) and 8 (b) show that variation of sole flue and crown temperature upto 38 hours, after that the temperature profile was found in normal condition and hence, the heating rate at centre was normal i.e. 0.60℃/min. | Figure 6. Temperature profile of oven no. 483 (a- Actual temperature profile; b- Predicted temperature profile) |

| Figure 7. Temperature profile of oven no. 136 (a- Actual temperature profile; b- Predicted temperature profile) |

| Figure 8. Temperature profile of oven no. 450 (a- Actual temperature profile; b- Predicted temperature profile) |

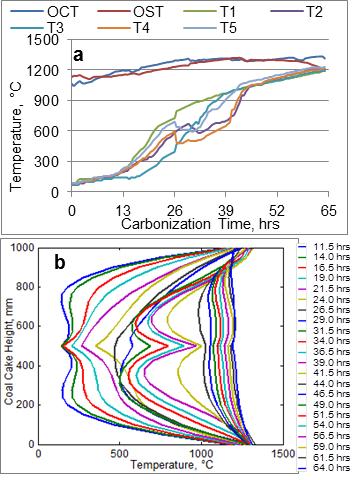

| Figure 9. Temperature profile of oven no. 406 (a- Actual temperature profile; b- Predicted temperature profile) |

| Figure 10. Temperature profile of oven no. 401 (a- Actual temperature profile; b- Predicted temperature profile) |

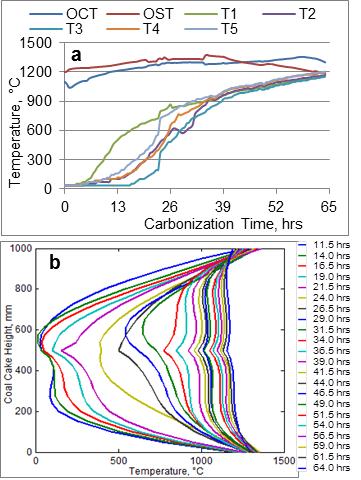

Figures 9 and 10 show the measured and predicted temperature profile of the oven number 406 and 401. Results show that the heating rate of oven number 406 and 401 varies in the range of 0.52-0.83℃/min and 0.50-0.78℃/min, respectively. These results show that the condition of oven number 406 is better compared to oven number 401. It is also observed that the oven regulations of the oven nos. 401 and 406 are not proper. These ovens are under repair because the suction ports of these ovens are chocked. Therefore, the progress of sole flue and crown temperature are not adequate as per desired requirements. Therefore, oven regulations or uniform heating of coke is an important key in coke making. Thus, homogeneous temperature distributions during the coking period are important for productivity, coke quality and battery life.

6. Conclusions

A mathematical model was used to predict the temperature profile of the non-recovery coke oven at different heights of coal cake. The three process parameters considered in this study were sole flue temperature, oven crown temperature and five different point temperatures of coal cake (200mm, 350mm and 500mm from bottom and top). The heating rate of normal operation was varied in the range of 1.06 -0.62℃/min at a height of 200mm from top & bottom and centre of the charged cake i.e. 500 mm from top and bottom.The mathematical model was developed for predicting the temperature profile at 50mm distance with an interval of 2.5 hours by using the set of experimental data and mathematical software package Matlab 7. The predicted values obtained using the models were in very good agreement with the experimental values. It was observed that the predicted temperature profile of the model can discriminate between operating conditions and works well even at lower level of temperature deviation. These variations will affect the heating rate and coking cycle, superimposed on the oven crown and sole temperature pattern. The model can be also used to predict the performance of carbonization throughout the coking cycle from top and bottom of coal cake towards the centre of the charge. It was found that an increase or decrease in sole flue and crown temperature pattern resulted in increase or decrease of the heating rates from top and bottom of the charged coal cake. The model also showed a decreasing trend of heating rate towards the centre of the charged coal cake which was actually observed in the plant.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors are thankful to Tata Steel management for giving an opportunity to work on this project. The support and services provided by staff of Hooghly Met Coke (HMC) division are also duly acknowledged.

References

| [1] | M S Oh, W A Peters & J B Howard, “An Experimental and Modeling Study of Softening Coal Pyrolysis”, AIChE Journal, Vol. 35, pp. 775-792, 1989. |

| [2] | C G Soth and C CRussel, “Source of Pressuring During Carbonization of Coal Reprint from Transactions”, AIME, 157, pp. 281 – 290, 1944. |

| [3] | S I Danilov, Yu A Chernyschov, “Coke and Chemistry USSR”, No. 4, pp. 7-10, 1984. |

| [4] | S Nomura, K M Thomas, Fuel, Vol. 75, No. 2, pp. 187 – 194, 1996. |

| [5] | D W Van Krevelen, “Coal Science and Technology 3”, Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Oxford-New York, pp. 264-302, 1981. |

| [6] | V S Romasko and N G Sanches, “Choice of the Parameters of Temperature Regime Coking”. Koks I Khimiya, No. 4, p. 13-16, 1995. |

| [7] | R Loison, P Foch and A Boyer, “Coke: Quality and Production” Butterworths, London, pp. 353-416, 1989. |

| [8] | Dr F Huhn, F Strelow and Dr W Eisenhut, “The Influence of Particular Raw Material and Operating Parameters on the Coking Mechanism”, Coke Making International, Vol. 3, No. 2, p. 37-43, 1991. |

| [9] | Kazuma Amamoto, “Coke Strength Development in the Coke Oven: 1. Influence of Maximum Temperature and Heating Rate, FuelVol. 76, No. 1, pp. 17-21, 1997. |

| [10] | Michael P Barkdoll and Richard W Westbrook, “Consistent Coke Quality from Sun Coke Company’s Heat Recovery Coke Making Technology, Coke Summit, p. 1-20, 2001. |

| [11] | David Merrick, “Mathematical Models of the Thermal Decomposition of Coal 1. The Evolution of Volatile Matter”, Fuel, Vol. 62, pp. 534-539, 2001. |

| [12] | David Merrick, “Mathematical Models of the Thermal Decomposition of Coal 2. Specific Heats and Heats of Reaction, Fuel, Vol. 62, pp. 540-546, 1983. |

| [13] | Brian Atkinson and David Merrick, “Mathematical Models of the Thermal Decomposition of Coal 4. Heat Transfer and Temperature Profiles in a Coke-Oven Charge, Fuel, Vol. 62, pp. 553-561, 1983. |

| [14] | Giles C Laurier, Paul J Readyhough and Geraid R Sullivan, “Heat Transfer in Coke Making”, Fuel, Vol. 65, pp. 1190-1195, 1986. |

| [15] | F Hanrot, D Ablitzer, J L Houzelot and M Dirand, “Experimental Measurement of True Specific Heat Capacity of Coal and Semi-coke during Carbonization, Fuel, Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 305-309, 1994. |

| [16] | D R Jenkins and M R Mahoney, Fissure Formation in Coke. 2. Effect of Heating Rate, Shrinkage and Coke Strength”, Fuel, Vol. 89, No. 7, pp. 1663–1674, 2010 |

| [17] | P P Kumar, A Kinlekar, K Mallikarjuna and M Ranjan, “Coal Pyrolysis and Kinetic Model for Non-recovery Coke Ovens”, Ironmaking and Steelmaking, Vol. 38, No. 8, pp. 608-612, 2011. |

| [18] | D R Jenkins, “Heat Transfer in the Charge of a Non-recovery Coke Oven”, METEC INSTEELCON® 2011. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML