Gilmara de Oliveira Machado1, Marcio Rogerio da Silva2, Victor Almeida De Araujo3, Juliano Fiorelli4, André Luis Christoforo5, Francisco Antonio Rocco Lahr6

1Department of Forestry, State University of Midwest (UNICENTRO), Irati, Brazil

2Department of Materials Engineering (SMM), Engineering School of São Carlos of University of São Paulo (EESC/USP), São Carlos, Brazil

3Research Group LIGNO of UNESP-Itapeva, Department of Forest Sciences, School of Agriculture Luiz de Queiroz of University of São Paulo (ESALQ/USP), Piracicaba, Brazil

4Department of Biosystems Engineering, Faculty of Animal Science and Food Engineering of University of São Paulo (FZEA/USP), Pirassununga, Brazil

5Centre for Innovation and Technology in Composites (CITeC), Department of Civil Engineering (DECiv), Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, Brazil

6Department of Structures Engineering (SET), Engineering School of São Carlos of University of São Paulo (EESC/USP), São Carlos, Brazil

Correspondence to: André Luis Christoforo, Centre for Innovation and Technology in Composites (CITeC), Department of Civil Engineering (DECiv), Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

To use more durable wood as a building material, thermal rectification is an alternative technique to reduce the wood decay against xylophages. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of the heat treatment on the density of Pinus oocarpa in temperatures at 200, 220 and 240°C during 30, 60 and 90 minutes. The samples were characterized by mass loss and gravimetric yield in order to verify the variations in the density of thermally treated wood. We found that heat treatment combinations up to 60 minutes and 220°C showed little variation in the density values. For longer time and at higher temperatures, due to the thermal degradation of the wood, there was a wide variation on density values accompanied by a decreasing tendency of the density. The highest density value was obtained at a time-temperature combination of 90 minutes and 220°C and the lowest at 60 minutes and 240°C. These results suggest that to apply the heat treated wood in construction purposes, better results were observed for thermal rectification that had little loss of density, since this property is directly related to less variation in strength and stiffness of wood.

Keywords:

Wood structures, Thermal treatment, Density

Cite this paper: Gilmara de Oliveira Machado, Marcio Rogerio da Silva, Victor Almeida De Araujo, Juliano Fiorelli, André Luis Christoforo, Francisco Antonio Rocco Lahr, Density Evaluation of Pinus oocarpa Submitted to Heat Treatment, International Journal of Materials Engineering , Vol. 5 No. 3, 2015, pp. 39-45. doi: 10.5923/j.ijme.20150503.01.

1. Introduction

Problems arising from wood biodeterioration can take on serious proportions, especially in tropical countries, and the adoption of treatment techniques using preservative process becomes mandatory when this material is intended to be used as a building material. For this purpose, it is necessary to increase the wood’s resistance to decay organisms.Some protection for wood can be obtained with surface coatings. However, the products used (paint, varnishes and lacquers) may be destroyed under external conditions. In relatively short time, the action of ultraviolet rays, rain and cycles of drying and humidification can destroy this protective film. Therefore, it is necessary to renew the coating periodically [1-3].The main method used to protect wood is by impregnation with preservatives. The treatment methods used include vacuum pressure impregnation and diffusion. The sapwood of many timbers can be fully impregnated and protected with preservatives, while heartwood is usually much less absorbent [1-3]. In order to inhibit deteriorations by xylophages, wood is often treated with relatively toxic substances. In addition to compound substances like creosote and amine-based preservatives, chemicals containing metals like copper, chromium, arsenic, boron, and zinc and halides like fluorine are also used. These preservative compounds present a number of concerns such as toxicity to humans, low biodegradability; and, in the case of heavy metals, accumulation in the environment. From an ecological perspective, additional difficulties can arise in the post-use disposal of treated timber. Therefore, it is desirable to use less toxic compounds for wood preservation [1-4].This study considers the use of the heat treatment, named thermal rectification, as an alternative technique to improve the wood decay against xylophages. The optimization of the thermal rectification process allows producing a material with lower hygroscopicity and with no significant decreasing in mechanical properties [5].Thermal rectification is defined as the product of the controlled pyrolysis, which is stopped before reaching the level of exothermic reactions (in temperatures about 280°C), when the combustion of wood starts [6]. Thermal rectification is a process in which thermal transport along a specific axis of the wood is dependent on temperature and time [7].This treatment promotes the volatilization of extractives and little thermal degradation of the main wood components as cellulose, lignin and hemicelluloses – this latter is the most affected. Thus, the xylophagous organisms reduce their interest in thermally treated wood as a food source, due to reduction of the hemicellulose content, which with the cellulose; they represent the main food base, as well as simple sugars, amino acids and fat – all of them present in the extractives composition.Wood under attack by decay fungi shows changes in chemical composition, which affects the mechanical properties [8]. These fungi degrade the cellulose and hemicelluloses, and consequently, there is loss of properties, whereas these macromolecules are responsible for the timber resistance [9].The xylophages attack also causes changes in the wood density, resulting from the mass loss, which is usually accompanied by its discoloration. Mass loss and discoloration are characteristics of an advance of wood decay. However, these guidelines are not always existent when they are used as tests to detect the wood decay, because due to the reasons of tree growth, wood can present discoloration and low specific density, when they are compared to the average values, a common fact in fast growth coniferous. Additionally, wood moisture content also affects its apparent density, with the modification of the natural color.According to Quirino [10], a low density and soft wood reaches higher surface hardness when it is thermally treated in autoclave, enabling their use in floors, although the changing in the original wood color. Furthermore, it has been found that this same treatment increases the resistance to wood decay by fungi. Stan [11] states that dimensionally stabilized wood by thermal treatment reaches considerable resistance to decay, and wide uses in construction.The commercial plantations of Pinus oocarpa were first established in Brazil in 1960 [12]. Because of its growth potential in areas with low fertility, the Pinus oocarpa has present in one of the most important conifer species for various subtropical and tropical Brazilian regions [13].In this research, thermal rectification wood of Pinus oocarpa in time combinations of 30, 60 and 90 minutes and temperatures of 200, 220 and 240°C were studied by means of its physical properties as gravimetric yield and mass loss, in order to evaluate the density variation. For construction purposes, the best performance is observed in wood with low density loss because this property is directly related to the wood strength and stiffness.

2. Material and Methods

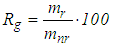

The specimens of Pinus oocarpa with dimensions of 2, 3 and 5 centimeters, moisture-free by drying, were carried out to thermal rectification tests in a laboratorial electric furnace (Ética model 400.4). The statistical design consisted in nine treatments with three variations of temperatures and three variations of time, with four repetitions per treatment. The specimens were carried out to the temperatures of: 200ºC during 30, 60 and 90 minutes; 220ºC during 30, 60 and 90 min; and 240ºC during 30, 60 and 90 min. After cooling in a desiccator, the thermally treated material was weighed and the gravimetric yield (RG) was determined with the use of the Equation 1 – where mr is the dry mass of the thermally treated specimen, and mnr is the mass of the non-treated specimen. | (1) |

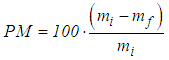

The percentage calculation of mass loss (PM) for thermal rectified wood is expressed by Equation 2 – where mi refers to the dry mass of the specimen before the thermal rectification and mf is the dry mass after the thermal rectification treatment. | (2) |

Wood density (ρap) at 0% moisture (Equation 3) was obtained by the ratio between the mass of the specimen verified in a semi analytical balance, and the volume measured using a digital caliper. In the Equation 3, ms is the dry mass of the dry specimen and vs is the volume of the dry specimen. | (3) |

After the thermal rectification test was realized the ratio (Equation 4) between the mass of thermally treated specimen (msr) verified in the semi analytical balance, and the volume of the thermally treated specimen (vsr) with a digital caliper. | (4) |

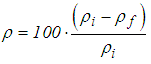

The value of the percentage loss of wood density (ρ) due to the thermal rectification is directly related to loss of mechanical strength of wood – very important indicative when the thermally treated wood is used in structures for construction. The loss of wood density is expressed by Equation 5, where ρi is the initial density of wood at 0% of moisture (before thermal rectification treatment), and ρf is the final density at 0% moisture after this thermal treatment. | (5) |

The factors and experimental levels initially investigated were: time - To (30, 60 and 90 min), temperature - Ta (200, 220 and 240ºC) and thermal rectification treatment - Tr (with and without heat treatment), verified in a full factorial design of 3221 type, providing 18 different treatments. The response-variable investigated was the wood density (ρ). Subsequently, the factors and experimental levels investigated were: time - To (30, 60 and 90 min) and temperature - Ta (200, 220 and 240ºC), which provided a planning with 9 treatments. For this second planning, the response-variables investigated were: mass loss of thermally treated wood (PM), percentage loss of density of the thermally treated wood (PD) and gravimetric yield (RG). The full factorial experiment, designed with the software Minitab® version 14, allowed to evaluate, according to the analysis of variance (ANOVA), the influence of the factors and interactions between them in the responses of interest.If it is significant the factor or interaction between both response, the main effect and interaction graphs was used to help in the interpretation of the results, followed by the multiple comparisons test of Tukey for grouping and classification of the significant factor groups.In order to validate the results obtained by ANOVA, they were evaluated by investigated the following properties: the normality on the residues distributions (Anderson-Darling test), the homogeneity of the variances of the residues among the treatments (Bartlett test) and the independence of the residues of ANOVA (residues×order).For Anderson-Darling test, at 5% of significance level, the formulated null hypothesis consisted to assume the normal distribution for the residues of ANOVA by property, consisting of non-normal distributions of the residues as an alternative hypothesis. Thus, if P-value is greater than the significance level of the test, this implies to accept the null hypothesis, refuting it otherwise. For Bartlett tests, at 5% of significance level, the formulated null hypothesis consisted to assume the equivalence among the variances of the residues and the treatments, and non-equivalence for the alternative hypothesis. If P-value is greater than the significance level, this implies to accept the null hypothesis, rejecting it otherwise.

3. Results and Discussions

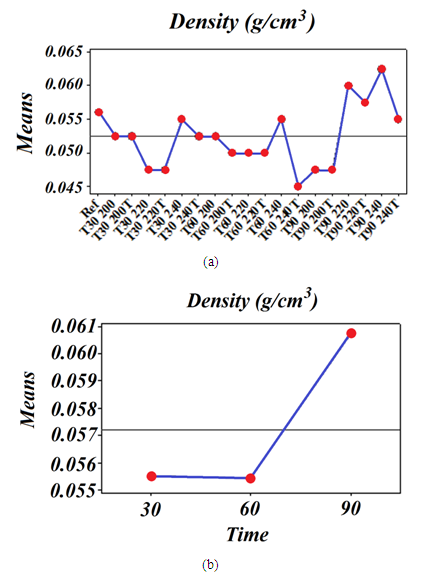

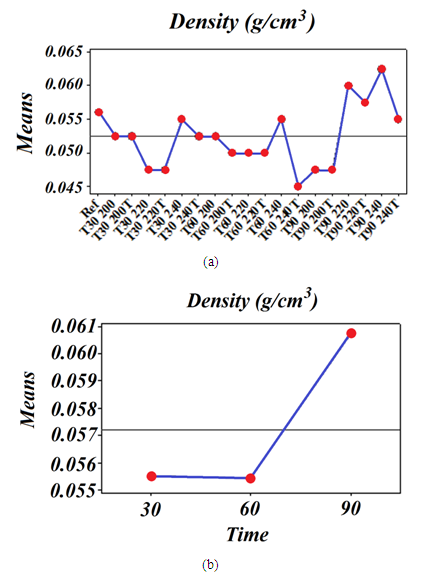

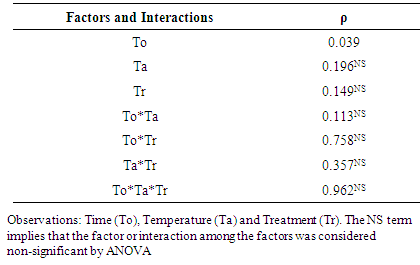

Wood is composed by polysaccharides (cellulose and hemicelluloses) and lignin, which are responsible by its physical, chemical and mechanical behavior. The process of thermal rectification promotes changes in these variables. Figure 1(a) illustrates the results of the density relating to the 18 treatments, including the reference condition (Ref – control). The reference sample consists in the average value of density for the non-treated specimens. In addition, it was determined the density of all the groups previously exposed to the thermal rectification process, and for the differentiation of these groups in relation to the thermally treated groups, the letter T was not used. Figure 1(b) presents the main effects graph for density. | Figure 1. Results of density of the reference samples (Ref), and of the samples before (without final letter T) and after the thermal rectification treatment (with final letter T) [a]; and the main effects graph for density [b] |

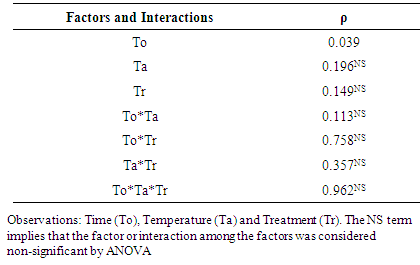

In Figure 1(a), for the combinations of time and temperature up to 60 min and 220ºC, a small variation in the density values was found, for example, non-treated samples of T30 200 group compared to the samples for the thermally treated samples of T20 200T. For major times and temperatures, there was a wide variation, comparing treated and non-treated samples, with a tendency of density decreasing for the thermally treated samples, fact which corresponds to a major degradation of hemicelluloses. From Figure 1(a), the largest density values for thermally treated wood were derived from the combination between 90 min and 220°C condition and the smaller in the 60min and 240°C combination, and only at 11.40% and 19.60% higher and lower respectively at the reference condition.Tables 1 and 2 present the results of the analysis of variance relating to the experimental design. In relation to the validation tests of ANOVA (normal distribution and equivalence of variance among groups), it is noteworthy that both were complied with in all investigated variable-response (P-value>0.05).Table 1. Results of ANOVA for density, and in B – results of analysis of variance for the mass loss, density loss and gravimetric yield

|

| |

|

Table 2. Result of the analysis of variance for mass loss, density loss and gravimetric yield

|

| |

|

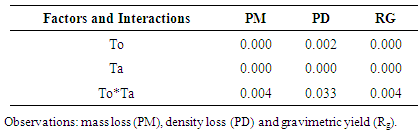

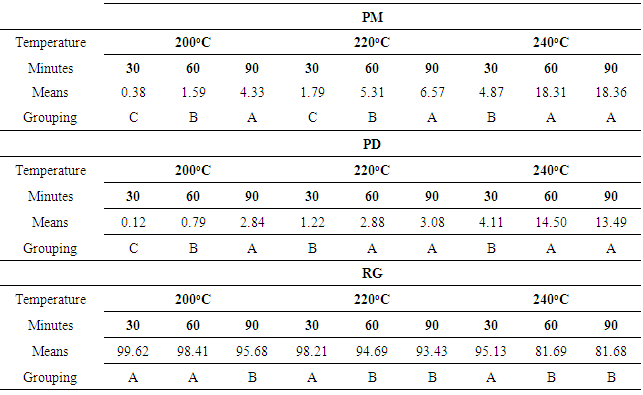

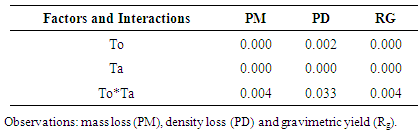

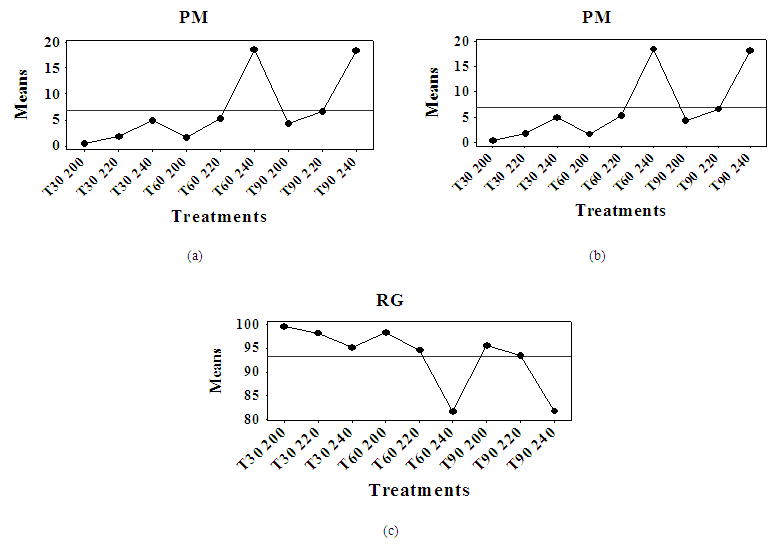

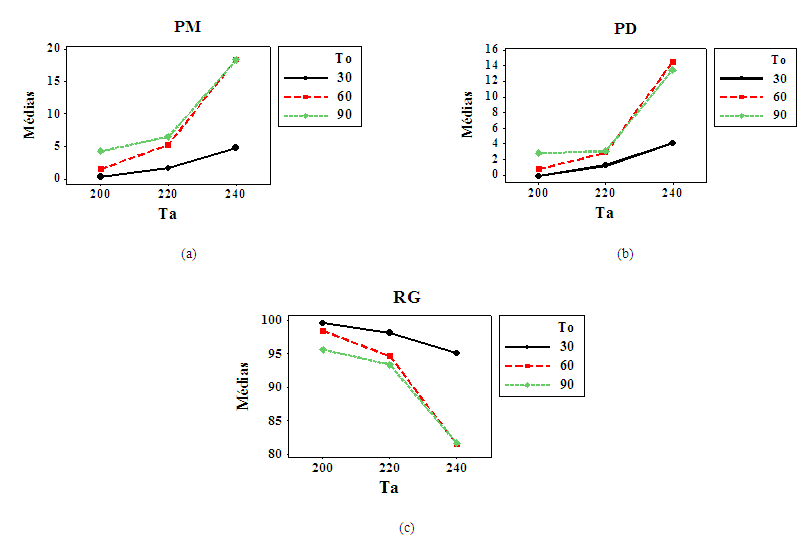

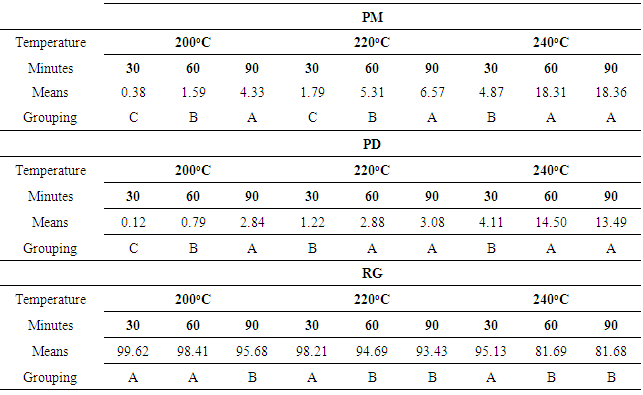

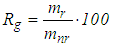

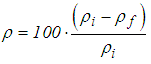

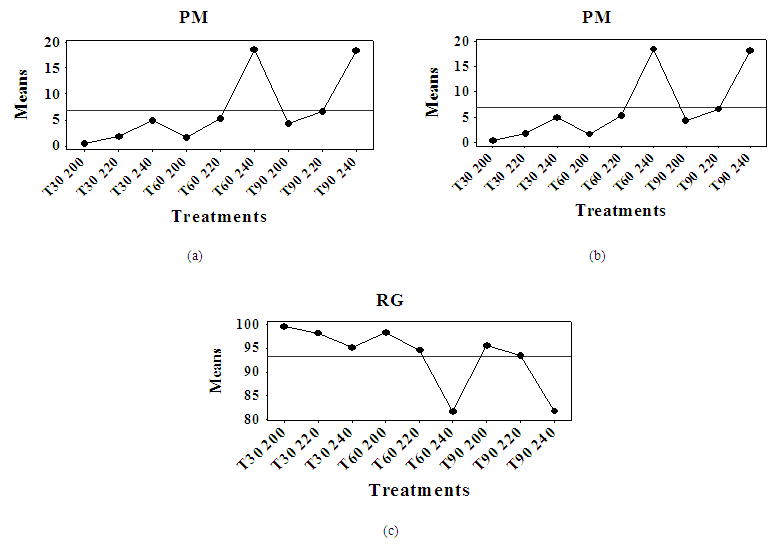

Among the analyzed variables, time (To) was the only factor which provided significant changes in density, because longer thermal rectification time corresponded to major modifications in the wood. Regarding the analysis of variance for the mass loss (PM), density loss and gravimetric yield (RG), the factors and interactions analyzed, all of them resulted in significant changes. Mass loss (PM), density loss (PD) and gravimetric yield (RG) are illustrated in Figure 2, with the specific changing of the obtained results in relation of each thermal rectification treatment.Figure 3 shows the graphs of interaction among factors considered significant by ANOVA (PM, PD and RG) and the Table 3 the results of the groups by Tukey test. It is noted that same letters imply in treatments with equivalent averages (means), and different otherwise. | Figure 2. Variation of the properties PM (a), PD (b) and RG (c) in relation to the treatments |

| Figure 3. Graphs of interaction among the factors for PM (a), PD (b) e RG (c) |

Table 3. Results of Tukey test

|

| |

|

ANOVA statistical analysis, followed by Tukey test, at 5% of significance, showed that the results for the density in 30 min and 50 min are equivalent. Silva [14] studied the process of thermal rectification of Eucaliptus citriodora and Pinus taeda woods, and He was verified that the changes in the density along the temperature increasing was not linear. Silva [14] still mentioned the fact of higher density happens at higher temperatures due to the variation in wood density. This fact is related to the ration between juvenile and mature woods, the differences between heartwood and sapwood and the different types of wood xylems. Thus, the factors described by Silva [14] may have influenced to obtain higher density in time of 90 min.Furthermore, in the Figure 1(a), it was observed that the density of non-treated samples for time of 90 min was higher than the others, and consequently, a higher density for thermally treated wood in this group. In addition, dimensional variations may occur simultaneously, which leads to volumetric contractions, and explains the higher densities obtained in longer times of treatments.The variation in the results of the mass loss (PM), density loss (PD) and gravimetric yield (RG) in relation to the treatments realized were shown in Figure 2. The highest mass loss were for the treatments T60 240°C and T90 240°C, and consequently the same groups showed higher density loss. The gravimetric yield was inversely proportional to the losses of mass and density, in which the smallest gravimetric yields were obtained for the treatments T60 240°C e T90 240°C.In general, higher indices of temperatures and thermal rectification times will result in major changes in the properties analyzed of mass loss, density loss and gravimetric yield. Figure 3 shows the graphs of interaction between the factors of time (To) and temperature (Ta) generated by ANOVA. Through the trend of Figure 2, but with a better understanding of the factors, it was possible to understand that, in the mass and density losses, the increasing of the temperature and time caused greater changes in wood thermally treated by the heat action. In the Figure 3, the results obtained for mass and density losses, in the temperature of 240°C (times of 60 and 90 min) were contrary to those expected. This fact was indicated by the difference in the initial density of the samples, which generated thermally treated groups with similar results. It is noteworthy that the density loss was different to the studied groups, and shorter levels of time and temperature evinced lower losses.The results of Tukey test for mass loss (PM), density loss (PD) and gravimetric yield (RG) were present in the Table 2, and with this test, the significant groups for: PM were T90 240ºC and T60 240ºC; for PD were T60 220ºC and T90 220ºC, T60 240ºC and T90 240ºC; and finally for RG were T30 200ºC and T60 200ºC, T60 220ºC and T90 220ºC, T60 240ºC and T90 240ºC.Thermal rectification treatment causes a mass reduction of the timber. According to Poncsák et al [15], the hemicelluloses are the most reactive components of the cell wall, due to its low molar mass, which degrade at low temperatures, among 160 and 220ºC. The cellulose degradation starts around 220ºC and the lignin undergoes changes above 250ºC [16]. Boonstra and Tjeerdasma [16] also describes that the mass loss and the consequent reduction in the apparent density of the thermally treated wood of Eucalyptus citriodora are associated with the degradation of the main chemical wood components (hemicelluloses, cellulose and lignin), and higher thermal rectification temperatures will reflect in major changes. Based on this literature, we conclude that alterations in the physical properties of thermally treated wood occurred because of changes of the main chemical components, as described by Silva [14].

4. Conclusions

Analyzing the density of thermally treated wood, based on the time factor, the highest density was obtained for the time of 90 min. Fact resulting from the variation in wood density, as described by Silva [14]. The increasing of the severity of the thermal rectification treatment caused higher wood changes, wherein the highest mass losses and the lowest densities were found for the treatment of 240ºC, with the times of 60 and 90 minutes. The best values obtained for the gravimetric yield occurred in the temperature of 200ºC with the time of 30 min. In consequence, the highest density losses and the highest gravimetric yields were for the same temperature. Statistical analysis revealed that the time and temperature factors directly influence the physical properties analyzed, and the time was the deciding factor for the changes generated by the heat action. The process of thermal rectification of wood in the conditions of temperatures of 200ºC and times of 30 and 60 minutes are recommended for structural uses of Pinus oocarpa constructions, whereas these changes have been minor.

References

| [1] | Lepage, E. S. Manual de preservação de madeiras. São Paulo, IPT, 2v, 1986. |

| [2] | Cavalcante, M. S. Deterioração biológica e preservação de madeiras. São Paulo, IPT, 40p, 1982. |

| [3] | Cassens, D. L. Selection and use of preservative: treated wood. Madison, Forest Products Society, 104p, 1995. |

| [4] | Delucis, R.A.; Gatto, D.A.; Cademartori, P.H.G.; Missio, A.L.; Schneid, E. Propriedades Físicas da Madeira Termorretificada de Quatro Folhosas. Floresta e Ambiente. 2014. 21(1): 99-107. |

| [5] | Gohar, P.; Guyonet, R. Development of wood rectification process at the industrial stage. 5th World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE). August 17-20, Lausanne – Switzerland, 1998. |

| [6] | Borges, L.M.; Quirino, W.F. Higroscopicidade da madeira de Pinus caribaea var. hondurensis tratado térmicamente. Revista Biomassa & Energia, v.1, n.2, p.173-182, 2004. |

| [7] | Roberts, N.A.; Walker, D.G. A review of thermal rectification observations and models in solid materials. International Journal of Thermal Sciences. 2010. 50(5):648-662. |

| [8] | Santos, Z. M. Avaliação da durabilidade natural da madeira de Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill: Maiden em ensaios de laboratório. 1992. 75 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciência Florestal). Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, 1992. |

| [9] | Mendes, A. S. A degradação da madeira e sua preservação. Brasília, IBDF/DPq-LPF, 1988. |

| [10] | Quirino, W. F. Utilização energética de resíduos vegetais. Brasília: IBAMA/LPF, 2003. |

| [11] | Stamm, A. J. Wood and cellulose science. New York: Ronald Press, 1964. 549p. |

| [12] | Nicolielo, N.; Garnica, J.B. Observações sobre o comportamento e o programa de melhoramento para Pinus oocarpa Schiede – Agudos-SP. Silvicultura. 1983. 29:119-120. |

| [13] | Kageyama, P.Y.; Vencovsky, R.; Ferreira, M.; Nicolielo, N. Variação genética entre procedências de Pinus oocarpa schiede na região de Agudos-SP. Revista IPEF. 1977. 14:77-120. |

| [14] | Silva, M. R. Efeito do tratamento térmico nas propriedades químicas, físicas e mecânicas em elementos estruturais de Eucalipto citriodora e Pinus taeda. 2012. 222 f. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências e Engenharia de Materiais). Universidade de São Paulo. São Carlos, 2012. |

| [15] | Poncsák, S; Kocaefe, D; Bouazara, M; Pichette, A. Effect of high temperature treatment on the mechanical properties of birch (Betula papyrifera). Wood Science Technology, v. 40, p.647–663, 2006. |

| [16] | Boonstra, M.J.; Tjeerdsma, B. Chemical analysis of heat-treated softwoods. Holzforschung, v.64, p. 204-211, 2006. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML