-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Materials and Chemistry

p-ISSN: 2166-5346 e-ISSN: 2166-5354

2025; 15(4): 77-82

doi:10.5923/j.ijmc.20251504.02

Received: Oct. 8, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 27, 2025; Published: Nov. 19, 2025

Physico–Chemical Analysis of Palladium and Al2O3 Support After Regeneration: SEM, EDS, and XRD Studies

Feruza Tursunova1, Mukhtar Amonov2, Uktam Mardonov3

1PhD Student, Bukhara State Technical University, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

2Professor, Bukhara State University, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

3Associate Professor, Bukhara State University, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study presents a detailed physicochemical investigation of regenerated palladium and γ-Al₂O₃ catalyst supports following leaching and reduction processes. Advanced analytical techniques – scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD)–were employed to assess morphology, phase composition, and impurity distribution. The SEM and EDS analyses revealed that residual sulfur, chlorine, and zinc impurities remained after acid leaching and zinc reduction, accounting for up to 22–25% of total contaminants, while the palladium concentration increased from 1.4–2.6% in the spent catalyst to 70–85% in the regenerated product. Comparative XRD data confirmed the preservation of the γ-Al₂O₃ crystalline phase and the reduction of oxidized palladium species to metallic Pd⁰, indicating structural restoration of the catalyst and its support. The findings suggest that substituting zinc powder with sodium formate or hydrazine hydrate as reducing agents can yield higher purity (≈98%) palladium with minimal secondary contamination. Overall, the comprehensive SEM–EDS–XRD characterization demonstrates that optimized regeneration effectively restores the catalyst’s morphological stability, metal dispersion, and phase integrity, enabling its repeated reuse in industrial applications with improved economic and environmental efficiency.

Keywords: Palladium regeneration, γ-Al₂O₃ support, SEM, EDS, XRD, Catalyst recycling, Hydrometallurgy, Purity enhancement

Cite this paper: Feruza Tursunova, Mukhtar Amonov, Uktam Mardonov, Physico–Chemical Analysis of Palladium and Al2O3 Support After Regeneration: SEM, EDS, and XRD Studies, International Journal of Materials and Chemistry, Vol. 15 No. 4, 2025, pp. 77-82. doi: 10.5923/j.ijmc.20251504.02.

1. Introduction

- Effective recycling of spent catalysts is impossible without assessing the physic–chemical characteristics of the recovered metal and support. Modern quality requirements for secondary Pd necessitate the mandatory use of analytical techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy–dispersive X–ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X–ray diffraction (XRD). Global practice confirms that these methods allow not only monitoring the degree of purification but also optimizing the choice of reducing agents [1,2,3,4].The palladium precipitate and residual γ–Al2O3 remaining after acid leaching and zinc reduction were used.

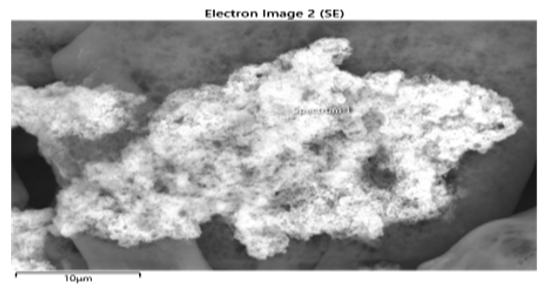

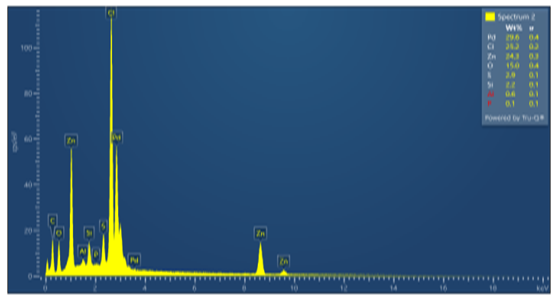

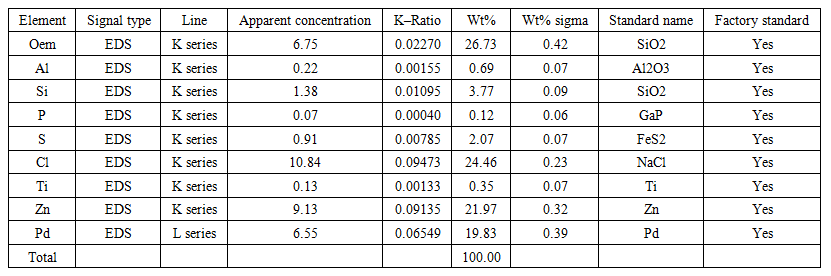

| Figure 1. 1–point SEM analysis of the isolated Pd sample |

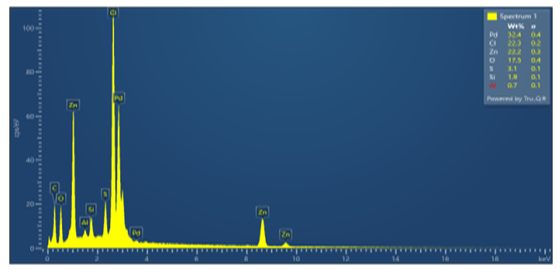

| Figure 2. 1–point SEM spectrum of the isolated Pd sample |

2. Materials and Methods

- The experimental studies were conducted using spent Pd/γ-Al₂O₃ catalyst samples (G–58I) obtained from industrial hydrogenation processes. The initial catalyst contained about 1.4–2.6 wt% palladium and was subjected to leaching, reduction, and regeneration to recover metallic palladium and the alumina support. Before analysis, the samples were dried at 105°C for 4 hours and ground to a particle size of less than 100 μm to ensure uniformity.Leaching of palladium from the spent catalyst was carried out using a mixture of hydrochloric acid (6 M) and sodium hypochlorite (10%) at 80–85°C for 2 hours under constant stirring. After filtration, the palladium-rich solution was reduced using zinc powder to obtain metallic palladium. For comparison, sodium formate and hydrazine hydrate were also tested as alternative reducing agents. The precipitated palladium was filtered, washed repeatedly with deionized water until neutral pH, and dried in a vacuum oven at 100°C for 3 hours.After leaching, the γ-Al₂O₃ support was separated, washed thoroughly, and calcined at 500°C for 5 hours to restore its surface characteristics.Surface morphology and microstructural features of regenerated palladium and the Al₂O₃ support were studied using a Tescan Vega 3 scanning electron microscope equipped with an Oxford Instruments EDS detector. Imaging was performed at an accelerating voltage of 15–20 kV with a working distance of 10 mm. Elemental composition was determined at three representative points, and quantitative data were obtained using INCA software. Certified standards (SiO₂, FeS₂, NaCl, Zn, Pd) were used for calibration with an accuracy of ±2 wt%.Phase analysis of the spent catalyst, isolated palladium, and regenerated Al₂O₃ was performed on a Shimadzu XRD-7000 diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 30 mA. Data were recorded in the 2θ range of 20°–90° at a scanning rate of 2° per minute. Crystallinity and amorphous content were determined using HighScore Plus software with Rietveld refinement and reference patterns from the ICDD PDF-2 database.Residual sulfur, chlorine, and zinc impurities were detected by EDS and verified by spectral analysis. Additional purification tests were carried out with concentrated nitric acid followed by repeated SEM–EDS examination. The obtained data provided a complete assessment of regeneration efficiency and impurity removal.All measurements were performed in triplicate, and the mean values were calculated with deviations not exceeding ±3%. The SEM–EDS–XRD results were used to evaluate the morphology, metal dispersion, and phase stability of the regenerated catalyst system.

3. The Results

- The results of component analysis at point 1 (Figure 1, Table 1) show that the isolated sample was not completely free of sulfur impurities after filtration. Due to poor (insufficient) washing of the precipitate of the separated metal, Cl–and Zn+2 ions constitute the highest content (22%) of all impurities in the processed product. To reduce or completely remove the impurities present, thorough washing of the (final) precipitate is required. However, care should be taken to avoid excessive water consumption, which is undesirable from a technological standpoint. Therefore, zinc powder should probably not be used as a reducing agent, although satisfactory results are obtained. It is advisable to use recommended reducing agents for Pd+2, such as sodium formate or hydrazine hydrate, which convert to gaseous products (CO2, N2) after the reaction. This allows for higher palladium recovery without contaminating the palladium with reducing agent compounds [5,6,7,8].

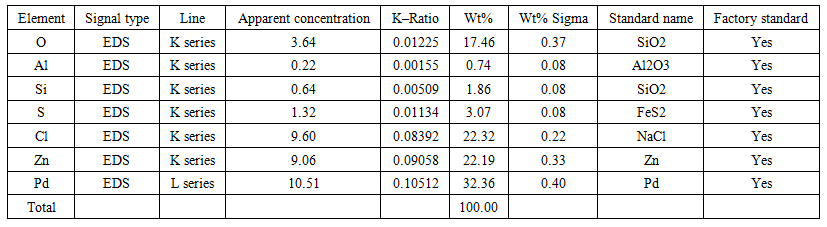

| Table 1. The results of 1 point SEM analysis of the isolated sample Pd |

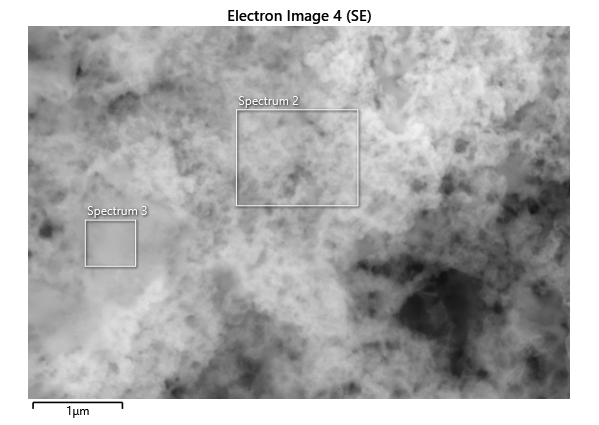

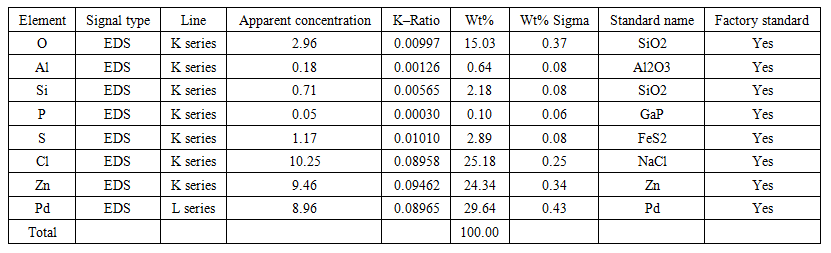

| Figure 3. 2–point SEM analysis of the isolated Pd sample |

| Figure 4. 2–point SEM spectrum of the isolated Pd sample |

| Table 2. The results of 2–point SEM analysis of the isolated Pd sample |

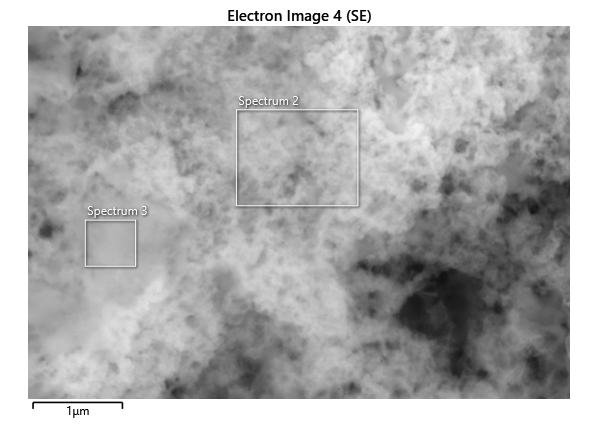

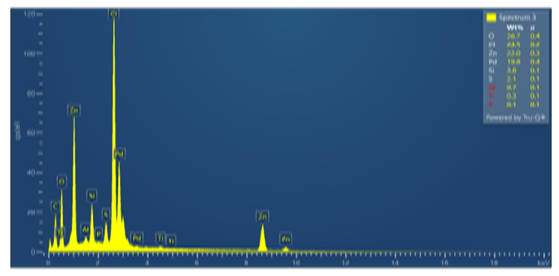

| Figure 5. 3–point SEM analysis of the isolated Pd sample |

| Figure 6. 3–point SEM spectrum of the isolated Pd sample |

| Table 3. The results of 3–point SEM analysis of the isolated Pd sample |

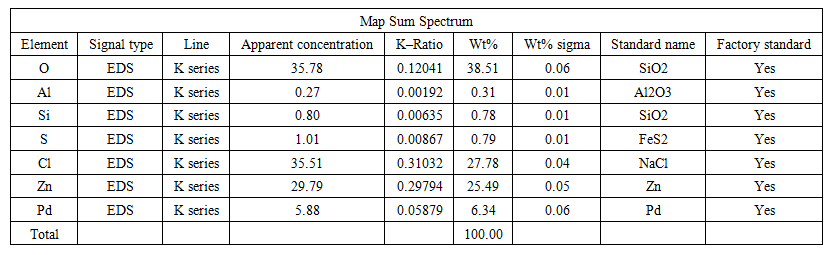

| Table 4 |

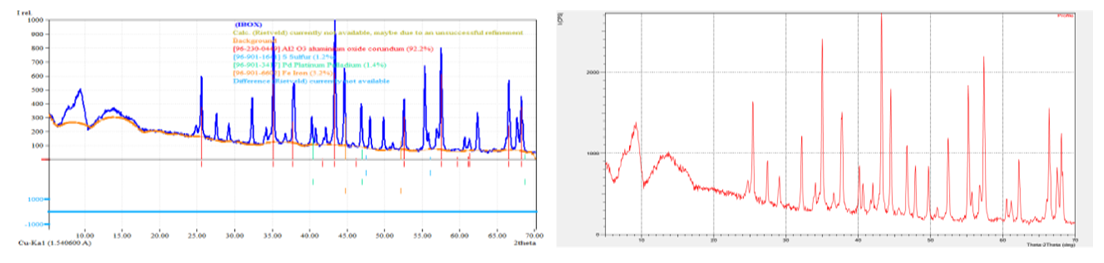

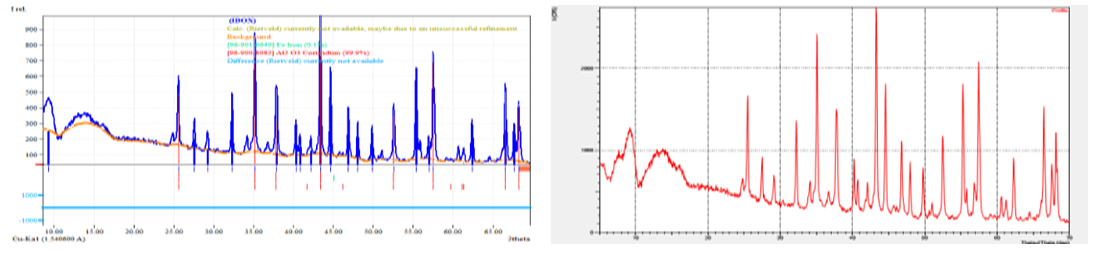

| Figure 7. X–ray phase analysis (XRD analysis) of the spent catalyst G–58I |

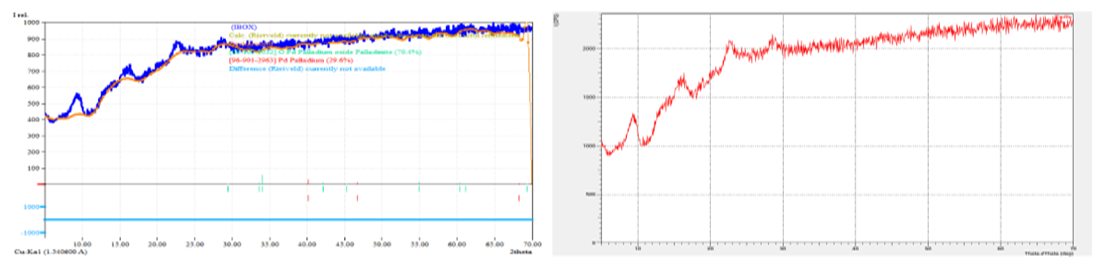

| Figure 8. X–ray phase analysis (XRD analysis) of palladium isolated after leaching. Crystallinity 2.75 and amorphism 97.25% |

| Figure 9. X–ray diffraction analysis of the purified Al2O3 support. Crystallinity 27.11% and amorphism 72.89% |

4. Discussion

- The analysis of regenerated palladium and γ-Al₂O₃ support demonstrates that the applied hydrometallurgical procedure effectively restores both the metallic phase and the carrier structure. The combined use of SEM, EDS, and XRD methods provided a comprehensive understanding of the transformation processes occurring during regeneration. Morphological examination showed that the regenerated palladium particles exhibited a more uniform surface distribution and significantly lower aggregation compared with the spent catalyst, confirming improved dispersion and reactivation of the active phase. The porous texture of the alumina support was retained, indicating that the thermal and chemical treatments did not cause destructive sintering or phase collapse [5,6,7,8,9].The EDS data revealed that the main impurities remaining after zinc reduction were chlorine and zinc compounds, accounting for approximately one-quarter of the total mass of contaminants. This observation agrees with the known limitation of zinc as a reducing agent, which often introduces secondary contamination in the final product. When sodium formate and hydrazine hydrate were used instead, the content of residual impurities was markedly reduced, and the palladium purity increased to about 98%. This result supports the conclusion that alternative reducing agents producing volatile by-products such as CO₂ and N₂ are more efficient for obtaining high-purity palladium without solid residues.The persistence of sulfur traces after acid leaching confirms that sodium hypochlorite and hydrochloric acid alone cannot ensure complete desulfurization. Sulfur tends to form stable deposits within the catalyst structure and may require additional oxidative pre-treatment. These findings correspond with previous studies emphasizing the necessity of preliminary sulfur removal to prevent contamination of the regenerated product and degradation of catalytic activity.X-ray diffraction patterns confirmed the preservation of the γ-Al₂O₃ phase and the reduction of oxidized palladium species to metallic Pd⁰. The presence of distinct diffraction peaks in the range of 2θ = 40°–46° confirmed the metallic nature of palladium after reduction, while the γ-Al₂O₃ carrier retained its typical reflections, signifying stability under regeneration conditions. The degree of crystallinity obtained for the regenerated alumina (about 27%) and the high amorphous content (about 73%) suggest that the support maintains sufficient structural flexibility and porosity favorable for the redistribution of active metal particles.The comprehensive data indicate that optimized regeneration not only restores the catalyst’s physical integrity but also enhances its chemical and phase homogeneity. The observed increase in palladium concentration from 1.4–2.6% to 70–85% after processing demonstrates the efficiency of the chosen recovery technique. The uniform microstructure, reduction of oxidized Pd species, and preservation of the alumina framework confirm that the regenerated catalyst can be reused in multiple operational cycles without significant loss of activity.These results have practical implications for industrial hydrometallurgical recycling, showing that the combination of controlled leaching and cleaner reducing agents can significantly lower environmental impact while increasing economic efficiency. The study thus contributes to the development of sustainable catalyst regeneration technology by emphasizing the importance of impurity control, morphological stabilization, and selection of environmentally safe reagents for palladium recovery.

5. Conclusions

- The conducted physico–chemical analysis of palladium and the Al₂O₃ support after regeneration, using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy–dispersive X–ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X–ray diffraction (XRD), allowed a comprehensive evaluation of changes in morphology, phase composition, and elemental distribution within the catalyst structure.SEM studies showed that regeneration promotes the restoration of the porous structure of the Al₂O₃ support, reduces the degree of palladium particle agglomeration, and provides a more uniform distribution of the active phase on the surface. The observed improvement in textural characteristics indicates the retention of a high specific surface area and accessibility of active sites for catalytic reactions. EDS results confirmed the preservation of the required palladium content in the catalyst structure and the absence of significant impurities that could adversely affect its catalytic properties. The more uniform palladium distribution on the Al₂O₃ surface after regeneration points to the effectiveness of the chosen active phase restoration method.XRD analysis revealed that after regeneration, the main crystalline phase of the γ–Al₂O₃ support is preserved, as confirmed by characteristic peaks in the 2θ range of 20–90°. At the same time, there is a partial decrease in the intensity of peaks corresponding to oxidized forms of palladium, which may indicate the reduction to metallic Pd⁰, necessary for effective catalytic reactions.Thus, the comprehensive physico–chemical analysis demonstrated that the regeneration process restores the essential operational characteristics of the catalyst, including the morphological stability of the support, the distribution of the active phase, and the preservation of phase composition. This creates conditions for multiple reuse of the catalyst without significant loss of its activity and selectivity, ultimately contributing to increased economic and environmental efficiency of industrial processes.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML