-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Materials and Chemistry

p-ISSN: 2166-5346 e-ISSN: 2166-5354

2025; 15(4): 71-76

doi:10.5923/j.ijmc.20251504.01

Received: Oct. 3, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 22, 2025; Published: Oct. 31, 2025

Dimensional and Morphological Properties of Nanodispersed ZnO Obtained on the Basis of the Spent Industrial Sorbent GIAP

Rayhona Muassarova1, Sarvarbek Koraev1, Gozzal Sidrasulieva2, Nuritdin Kattaev3, Khamdam Akbarov3

1PhD Student, Department of Physical Chemistry, National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2PhD, Department of Physical Chemistry, National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

3DSc, Professor, Department of Physical Chemistry, National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Rayhona Muassarova, PhD Student, Department of Physical Chemistry, National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

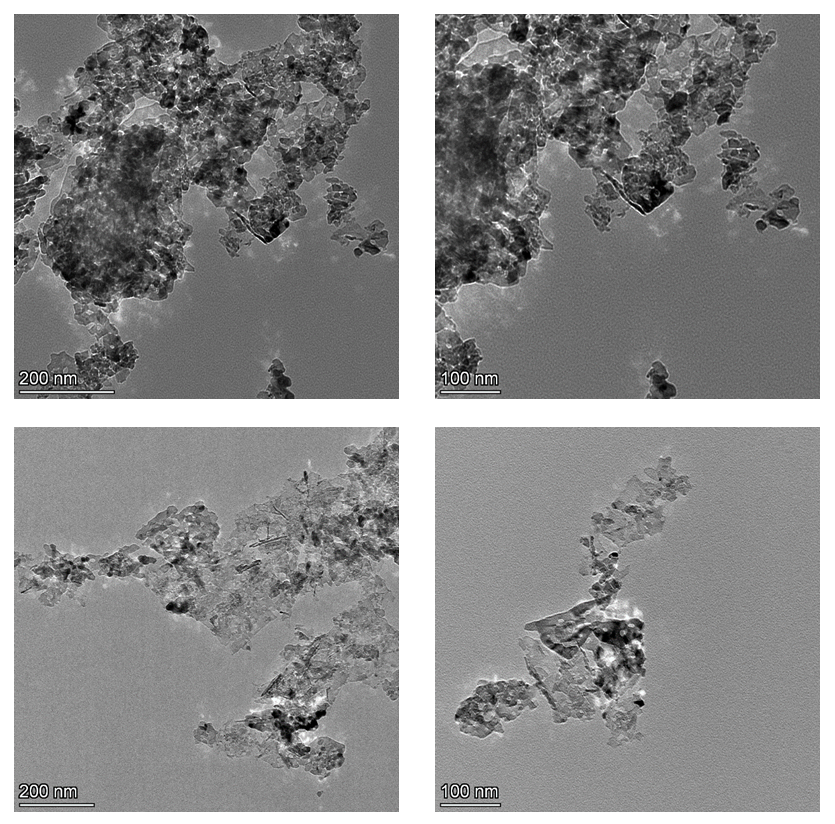

Nanostructured zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles were synthesized using zinc carbonate derived from local catalytic waste (GIAP-10) as a sustainable secondary raw material. The synthesis procedure involved the conversion of zinc carbonate to zinc nitrate, controlled precipitation with ammonia, hydrothermal treatment at 180°C, and final calcination at 350°C. The obtained ZnO was comprehensively characterized by SEM, TEM, EDS, and DLS. SEM images revealed a granular surface structure with interparticle porosity, while TEM analysis confirmed the coexistence of granular nanoparticles (10–40 nm) and nanosheets (5–25 nm thick, up to 100 nm long), forming a porous hierarchical system. EDS spectra and elemental mapping indicated high purity and homogeneous distribution of Zn and O across the material, with negligible impurities. DLS measurements revealed a bimodal size distribution, with the dominant fraction (~73%) corresponding to nanoparticles of ~8–9 nm and a secondary fraction (~26%) representing aggregates (~175 nm). The structural purity, nanoscale dimensions, and morphological diversity of the synthesized ZnO make it a promising candidate for applications in photocatalysis, gas sensing, and functional nanocoatings. Importantly, the use of industrial waste as a precursor highlights both the ecological and economic advantages of this approach, providing an efficient pathway for the valorization of secondary raw materials.

Keywords: ZnO nanoparticles, Hydrothermal synthesis, Morphology, Photocatalysis, Waste recycling

Cite this paper: Rayhona Muassarova, Sarvarbek Koraev, Gozzal Sidrasulieva, Nuritdin Kattaev, Khamdam Akbarov, Dimensional and Morphological Properties of Nanodispersed ZnO Obtained on the Basis of the Spent Industrial Sorbent GIAP, International Journal of Materials and Chemistry, Vol. 15 No. 4, 2025, pp. 71-76. doi: 10.5923/j.ijmc.20251504.01.

1. Introduction

- Zinc oxide (ZnO) is one of the most versatile functional materials widely applied in photocatalysis, optoelectronics, gas sensing, energy storage, and antibacterial coatings. Its outstanding performance arises from unique physicochemical properties, including a wide band gap (3.37 eV), high exciton binding energy (60 meV), strong UV absorption, and tunable surface activity [1, pp. 12–15; 2, pp. 45–48]. At the nanoscale, ZnO exhibits enhanced catalytic efficiency, improved light harvesting, and increased sensitivity in sensor devices due to its large specific surface area and size-dependent electronic structure [3, pp. 90–94; 4, pp. 103–107]. For these reasons, the development of reliable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly methods for synthesizing ZnO nanoparticles remains an important direction in nanomaterials research.A wide range of synthesis techniques has been reported for ZnO nanostructures, including sol–gel methods, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), precipitation, solvothermal and hydrothermal processes [5, pp. 30–35]. Among them, hydrothermal synthesis is considered particularly advantageous because it allows precise control of morphology, crystallinity, and particle size under relatively mild conditions [6, pp. 20–24]. Furthermore, it is scalable, energy-efficient, and compatible with sustainable materials processing. The ability to tailor the morphology – granular nanoparticles, nanorods, nanosheets, or hierarchical assemblies–directly determines the functional properties of ZnO in different applications [7, pp. 200–205].Another important aspect of modern nanomaterials synthesis is the utilization of industrial by-products and secondary raw materials. The valorization of waste streams not only reduces environmental pollution but also provides a cost-effective feedstock for the production of high-value nanostructures [8, pp. 50–52]. In this context, catalytic waste streams, such as GIAP-10 (a zinc hydroxyaluminate-based sorbent used for the removal of hydrogen sulfide from coke gas), represent a promising source of zinc-containing compounds. Transforming such waste into nanostructured ZnO provides both ecological and economic benefits, contributing to the principles of sustainable development and circular economy.In recent years, several studies have reported on the synthesis of ZnO from industrial wastes, including metallurgical residues, fly ash, and spent catalysts. However, systematic investigations of size–morphological features of ZnO nanoparticles derived from catalytic sorbents are still limited. A detailed characterization of particle size distribution, morphology, and structural purity is crucial for establishing correlations between synthesis conditions and functional performance.Therefore, the present work focuses on the synthesis of nanostructured ZnO from catalytic waste GIAP-10 using a hydrothermal method, followed by calcination. Comprehensive characterization by SEM, TEM, EDS, and DLS was carried out to evaluate the size, morphology, elemental composition, and aggregation behavior of the obtained ZnO. Special attention was paid to identifying granular versus sheet-like morphologies, the presence of hierarchical porosity, and the degree of purity. The findings are expected to provide new insights into sustainable ZnO nanoparticle production from secondary raw materials and to expand their potential applications in photocatalysis, sensing, and functional nanocoatings.

2. Materials and Methods

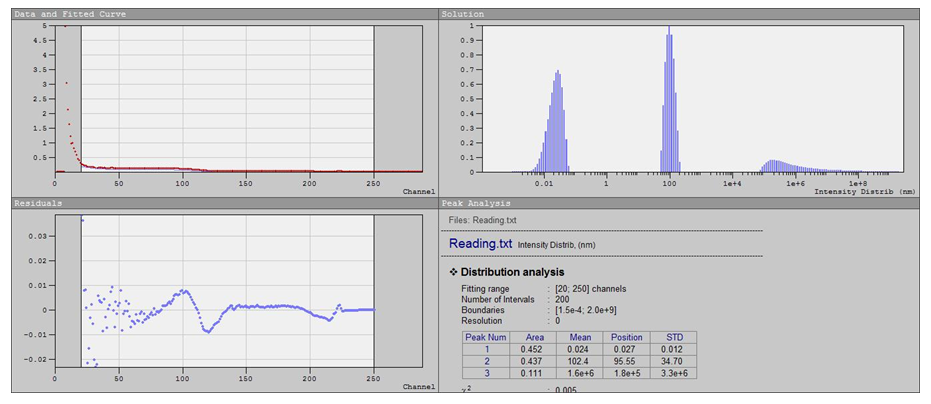

- Materials. Zinc carbonate was used as the starting raw material. It was preliminarily extracted from catalytic waste GIAP-10 (local industrial source, Uzbekistan) [8, pp. 50–52]. Distilled water and ethanol (reagent grade, Sigma-Aldrich) were employed for synthesis and washing procedures. Nitric acid (HNO₃, 65%, analytical grade) was used to dissolve the raw material, and a 25% aqueous ammonia solution (NH₄OH, analytical grade) served as the precipitating agent. All reagents were used without further purification.Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles. The synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles was carried out in several sequential steps:Preparation of zinc nitrate. Zinc carbonate was neutralized with nitric acid until the pH reached 7, resulting in the formation of a transparent zinc nitrate solution. The obtained solution was evaporated in a drying oven at 60°C until crystallization.Precipitation of ZnO precursor. The crystallized Zn(NO₃)₂ was dissolved in a minimal amount of distilled water and, under continuous stirring on a magnetic stirrer, a 25% ammonia solution was slowly added. The pH was maintained in the range of 9–10, which led to the formation of an intense white precipitate. After precipitation, the suspension was additionally stirred for 30 min to ensure homogeneity.Hydrothermal treatment. The resulting suspension was transferred into a 100 mL stainless-steel autoclave equipped with a Teflon liner. Hydrothermal processing was performed at 180°C for 8 h.Washing and thermal treatment. After cooling to room temperature, the product was repeatedly washed: three times with distilled water and three times with ethanol. The washed material was dried at 80°C and subsequently calcined at 350°C for 2 h in air to stabilize the crystalline structure [5, pp. 30–35; 6, pp. 20–24].Characterization methods• Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The morphology of ZnO nanoparticles was examined using a field-emission scanning electron microscope at magnifications ranging from ×100 to ×1000. Images were recorded to observe particle shape, surface features, and agglomeration behavior.• Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS). Elemental composition and distribution of zinc and oxygen were studied by EDS mapping and energy spectra in the 0–10 keV range. The uniformity of elemental signals was used to confirm phase purity and chemical homogeneity [7, pp. 200–205].• Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). High-resolution TEM was employed to investigate the fine morphology, crystallinity, and size distribution of the nanoparticles. Both granular and sheet-like morphologies were identified at different scales (100–200 nm).• Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Hydrodynamic size distribution of nanoparticles in suspension was measured by DLS in the range of 0.1–1000 nm. The bimodal distribution profile was analyzed in terms of primary nanoparticles and secondary aggregates [9, pp. 145–147].

3. Results and Discussion

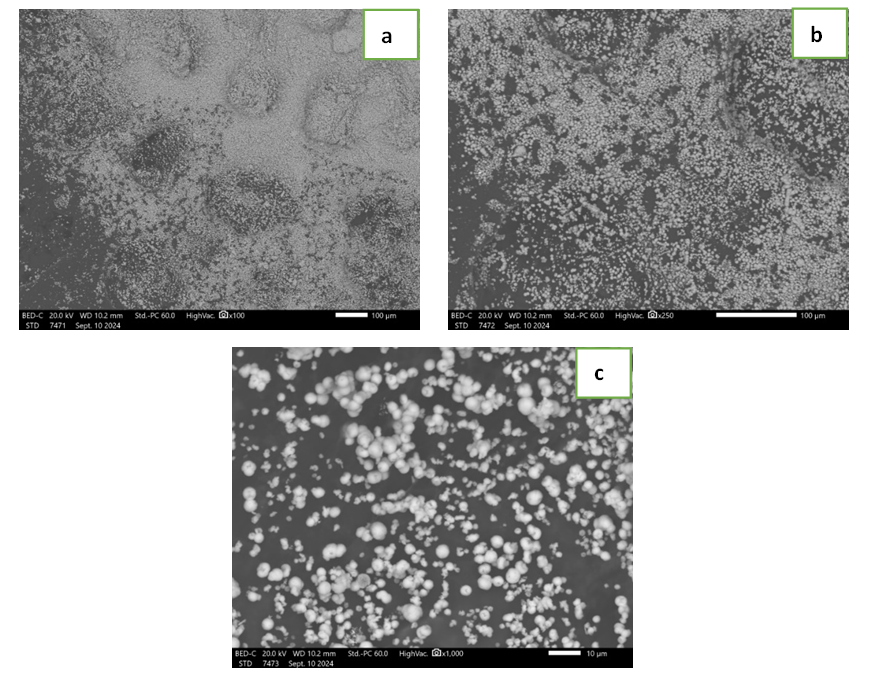

- The morphological and size characteristics of the synthesized ZnO nanoparticles were comprehensively studied using a set of complementary techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and dynamic light scattering (DLS). This combined approach made it possible to characterize not only the appearance and shape of the individual particles but also their aggregation behavior, elemental homogeneity, and particle size distribution. The results demonstrate that the hydrothermal synthesis route, based on local secondary raw materials, yields nanodispersed ZnO with pronounced structural heterogeneity, which is expected to strongly influence its physicochemical performance.SEM images revealed that the ZnO sample formed a loose granular layer composed of small particles with predominantly spherical morphology. At low magnification (×100), large aggregates measuring 10–30 μm were observed, separated by intergranular voids [9, pp. 145–147]. This type of architecture reflects a hierarchical organization in which small nanoparticles assemble into larger agglomerates, forming a porous network with enhanced surface accessibility. Such open porosity is highly beneficial for diffusion-controlled processes, particularly catalysis and adsorption (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. SEM images of ZnO nanoparticles at magnifications of ×100 (a), ×250 (b) and ×1000 (c) |

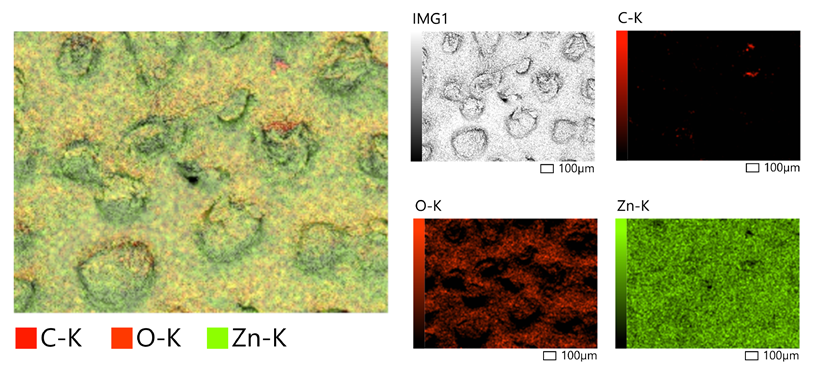

| Figure 2. Distribution map of elements in nano-ZnO |

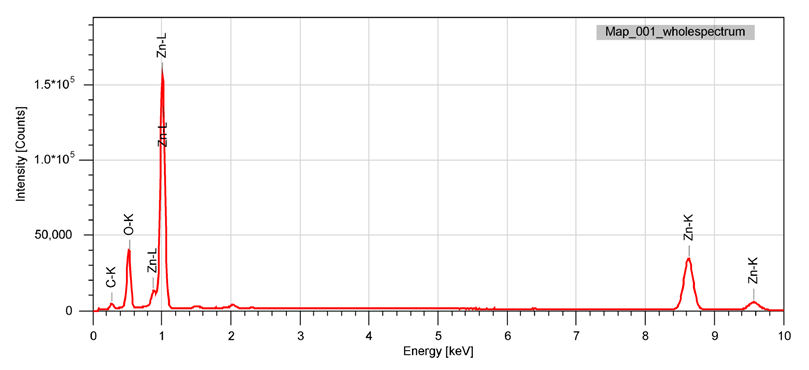

| Figure 3. Energy dispersive (EDS) spectrum of nano-ZnO |

| Figure 4. TEM image of ZnO nanoparticles |

| Figure 5. Results of measuring the size distribution of ZnO particles using the DLS method |

4. Conclusions

- A sustainable synthesis pathway for nanostructured ZnO nanoparticles from local secondary raw material (catalyst waste GIAP-10) was successfully established. The multi-step process involving nitrate formation, controlled precipitation, hydrothermal treatment, and calcination yielded high-purity ZnO with stable nanostructural features.Morphological studies (SEM, TEM) revealed that the product consists mainly of nanoparticles sized 8–40 nm, partially aggregated into clusters up to several hundred nanometers. The coexistence of granular and sheet-like morphologies leads to a porous hierarchical architecture with enhanced surface accessibility. EDS confirmed the uniform distribution of Zn and O without significant impurities, while DLS analysis showed a bimodal size distribution, reflecting both individual particles and secondary aggregates.The structural purity, morphological diversity, and nanoscale dimensions of the synthesized ZnO highlight its strong potential for applications in photocatalysis, gas sensing, optoelectronics, and functional coatings. Furthermore, the valorization of catalytic waste as a precursor underlines the ecological and economic relevance of this approach, providing an efficient route to high-value nanomaterials within a sustainable framework.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML