-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Modern Botany

p-ISSN: 2166-5206 e-ISSN: 2166-5214

2013; 3(2): 25-31

doi:10.5923/j.ijmb.20130302.03

Desmids of Osse River, Edo State, Nigeria

O. Ekhator, J. O. Ihenyen, G. O. Okooboh

Department of Botany, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State

Correspondence to: O. Ekhator, Department of Botany, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper presents a pioneer investigation of the desmids of Osse River, in Ovia-North East Local Government area of Edo State. Desmids samples were collected monthly in the open water from January 2003 to April 2004 using plankton net of 55µm mesh size. Fifty taxa were observed comprising eleven genera: Closterium (13), Actinotaenium (1), Bambusina (1), Cosmarium (9), Desmidium (3), Euastrum (2), Hyalotheca (1), Micrasterias (9), Pleuroteanium (7), Triplocerus (1) and Gonatozygon (3). Desmids abundance decreased as the study progressed towards the brackish environment. Wet season count was higher than that of the dry season. The genera represent the first reported list for Osse River.

Keywords: Desmids, Plankton, Taxa

Cite this paper: O. Ekhator, J. O. Ihenyen, G. O. Okooboh, Desmids of Osse River, Edo State, Nigeria, International Journal of Modern Botany, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 25-31. doi: 10.5923/j.ijmb.20130302.03.

1. Introduction

- Desmids are unicellular micro-organisms belonging to the green algal families of Mesotaeniaceae and Desmidiaceae which occur mostly in standing freshwaters. They belong to the division Chlorophyta and order Zygnematales[1]. Desmids are of two types- true desmids (placoderm) and false (saccoderm) desmids. The true desmids are characterized by symmetrical semi cells with an incision at the middle termed isthmus with pores, while the false desmids are smooth walled, without pores and a median constriction[2]. Desmids are recognized to constitute an important group of organisms in the trophic classification of freshwater[3].Desmids have been identified as characteristic elements of epiphytic communities[4] which can be used in environmental assessments. Several species of this group have been found to be closely related to certain types of aquatic habitats, and may be used as indicators of changes of pH or nutrient supply[5-7]. Desmids have also been used for assessing the nature conservation value[8] of aquatic habitats. This makes desmids an important area of research. Moreover, there is a need for the compilation of clear records of desmids and taxonomic guides for use in regions like Nigeria, where hydrobiology and its applications are still in relative infancy[3, 9]. Desmids have been studied by several authors in different countries including the works of[10],[11],[12], who studied desmids in selected rivers in India;[13] made some remarkable findings on desmids in Botswana and Namibia,[14] on desmids in the Maarsseveen lakes in Netherlands. Desmids from lakes and ponds of Sindh in Pakistan have been studied by[15]. Earlier researches on the presence of desmids in African rivers include the works of[16, 17] and[18] conducted in South Africa.[19] and[20] further investigated desmids from Sudan in North Africa. [21] gave an in-depth account of the desmids in Egypt.[22] studied Sierra Leone desmids,[23] also in Sierra Leone studied desmids from Guma valley.[24, 25] made their investigations on Ghana desmids while[26, 27] concentrated on the desmids of Uganda and other East African countries. In Nigeria, early works on desmids include[28] which listed 48 taxa in 12 genera. Other records are 40 taxa of Closterium [29]; 21 taxa of Micrasterias[9, 30]; 28 taxa of Cosmarium [31]; 24 taxa of some desmids including Pleurotaenium and Gonatozygon[32, 33], 31 taxa including Actinotaenium and Desmidium[34], 20 taxa of contrasting spring desmids including Cosmarium and Euastrum[35].[36, 37] reported ninety taxa belonging to seventeen genera while[38] reported 106 taxa belonging to twenty genera and most recently[1]. [39] reported only 3 taxa, Closterium, Gonatozygon, and Staurastrum from Iyagbe lagoon. Despite this enormous research in the area of desmids, presently, there is no published work on desmids on Osse River. Our study focuses on assessing desmids occurring in Osse River in Edo State, Nigeria.

2. Study Area

- The Osse River originates in the Akpata hills in Ekiti State, Nigeria. It flows through Ovia North-East Local Government Area and empties into the Benin River, which is one of the four major rivers that drain into the Atlantic Bight of Benin. Others being Ramos, Forcados and Escravos River. The climate has the unique features of the humid tropical wet season and dry seasons. In the wet season, the river is characterized by increased flow rate, high turbidity and muddy water especially after heavy rainfall. The dry season on the other hand is characterized by moderate or slow flow rate and clearer water. Several streams and creeks drain into the Osse river. The river is the major source of drinking water for the inhabitants of communities surrounding it[40].The project area lies north of the equator. Thus the climate of the study area is typical of the humid tropics with considerable influence resulting from its nearness to the sea (Atlantic Ocean). The two (2) dominating air masses are the drier Tropical Continental (TC) from the Sahara in the north and the humid Tropical Maritime (TM) from across the Atlantic Ocean in the south. The major elements of the climate are the wind (direction and speed), relative humidity, rainfall distribution, temperature, and sunshine hours. The interplay between all the enumerated factors results in the climatic element of the study area. During the field work, the wind direction was predominantly south westerly for the wet season (October 2013) and North-Easterly for the dry season (February 2013). The wind speed varied from 0.1 – 2.0m/s for the wet and 0.1- 3.0m/s for the dry seasons. The relative humidity of the area shows that relative humidity values are high all year round at an average of 80.5% and are typical of equatorial climate. Recorded values during study period ranged from 54.1-95.6% for the wet season and 32.3-90.7% for the dry season. These values generally fall within the historical data average for the ecological zone.The project area is located within the equatorial belt that experiences high rainfall for most of the year. The mean annual rainfall often exceeds 2200mm. Temperatures are usually high and vary little year round which is typical of the equatorial belt. Historically, the mean temperature for the hottest months (February/March) is 34℃ while that of the coolest month (August) is 28℃. Air temperatures recorded during the field work were between 23.7 and 35.6℃ and 24.4 and 36.4℃ during the wet and dry seasons respectively. The mean annual sunshine hours in the area are about 1,537 hours. The mean monthly values vary between 51.6 and 176.7 hours in the months of July (wet) and December (dry) respectively. The generally low amount of sunshine hours in July is due to the greater amount of cloudiness and rainfall characteristics of the region. Conversely, the higher December value is due to the prevalent clear skies when the ITD has once more started its northward migration. Cloud cover ranged from 7.0oktas to 7.3oktas in the wet season and 7.0oktas to 7.1oktas in the dry season[41]. Five stations along the river were investigated; station 1, (Nikorogha), station 2, (Ekenhuan), station 3, (Tolofa), station 4(Ogeba) and station 5(Ureju). Stations 4 and 5 are brackish environments while stations 1, 2 and 3 are freshwater areas.

3. Methodology

- The desmids samples were collected monthly in the open water using plankton net of 55µm mesh size tied unto a motorized boat and towed at low speed for 5minutes. The net catches were transferred into 200ml properly labelled plastic containers and immediately preserved with 4% formalin solution. Samples were examined with a Leitz Orthoplan Research Microscope equipped with tracing and measuring devices at the phycology laboratory in University of Benin, Benin City. Relevant texts used for identification include[37, 9 and 33]. For quantitative studies, sample was preserved with 4% formalin solution in 250ml plastic container and concentrated to 10ml in the laboratory. Two drops from this 10ml were used for each sample mount. Ten mounts were taken and phytoplankton cells counted in each mount as described by Lackey[42]. The average was taken to get the relative number of organisms per ml.

4. Results

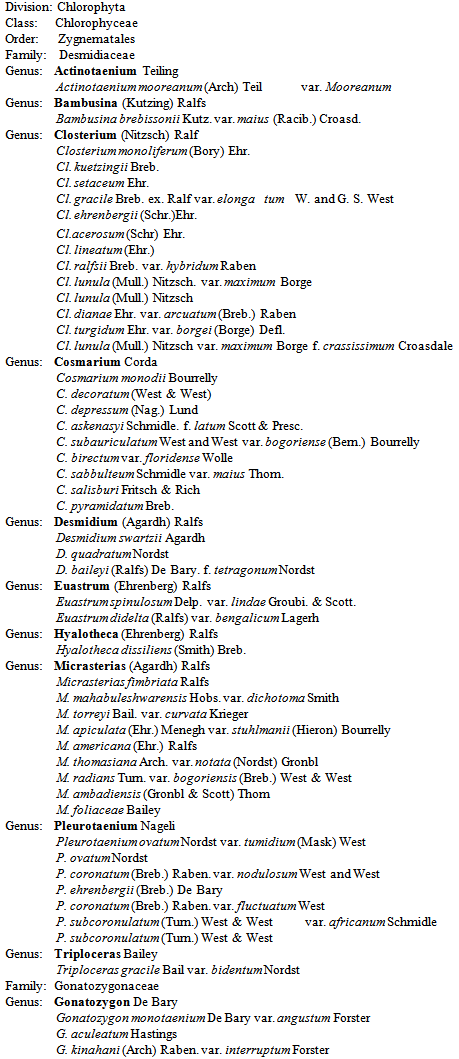

- A total of 50 taxa were identified belonging to 11 genera; Actinotaenium (2%), Bambusina (2%) ,Cosmarium (18%), Desmidium (6%), Euastrum (4%), Hyalotheca (2%), Micrasterias (18%), Pleurotaenium (14%), Triploceras (2%,) Gonatozygon (6%) and Closterium which is the most frequently occurring of all genera throughout the period of sampling making up to 13 species (26%).The taxa are arranged below.A checklist of desmids from Osse River, Edo State, Nigeria.

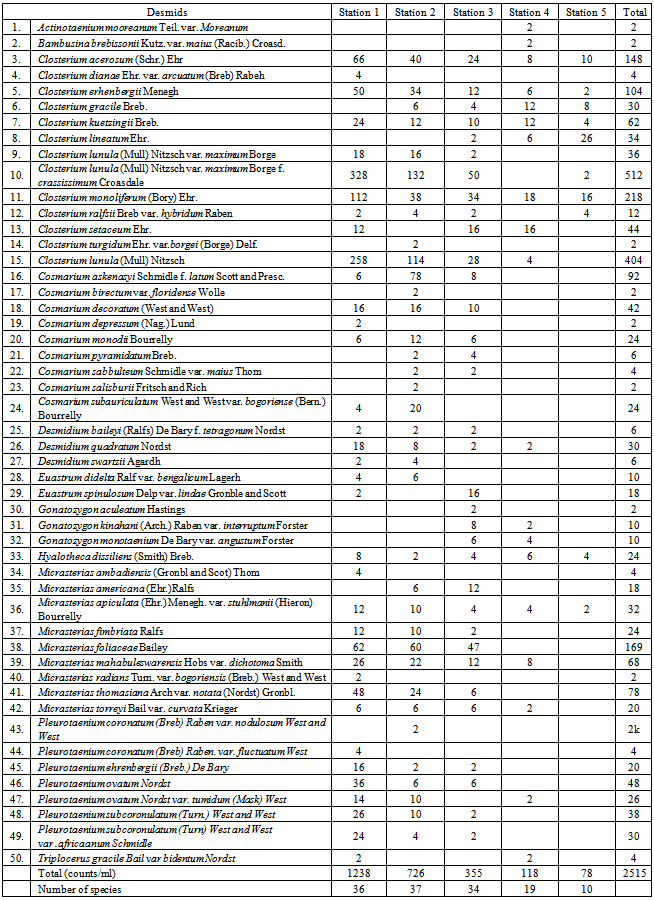

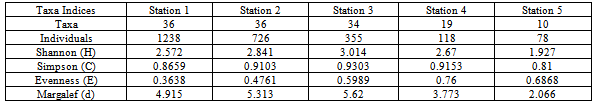

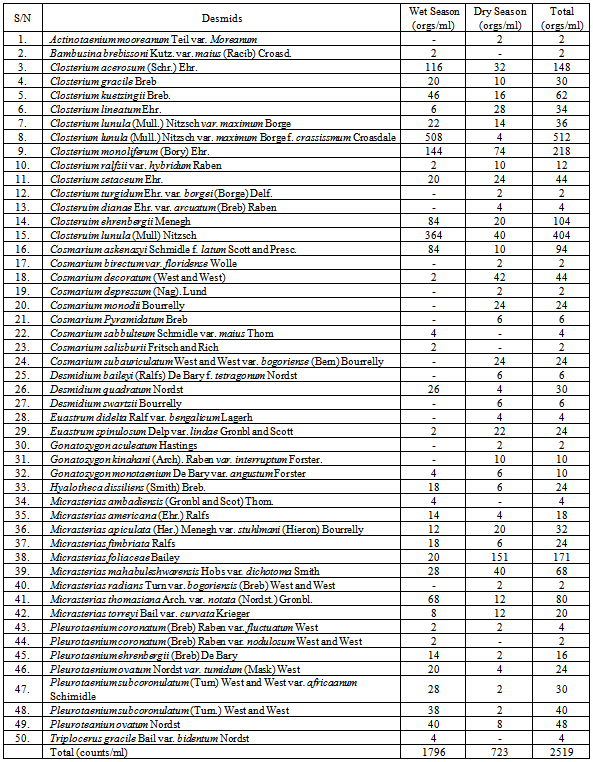

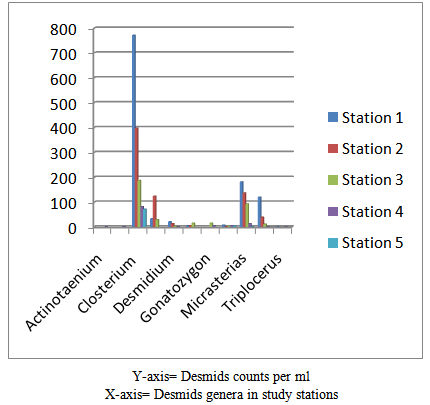

Desmid counts decreased towards the brackish environment (Table 1)Closterium and Micrasterias genera recorded the highest number of individuals in the study followed by Cosmarium. Few species of desmids are represented in stations 4 and 5 while stations 1, 2 and 3 recorded more desmids (Fig 1).Species abundance was more in stations 1, 2 and 3 (Table 2). Species diversity (H), was high in station 1 to station 4, with the highest being station 3. Species diversity was lowest in station 5. Dominance (C) and evenness (E) were low in the study stations. Species richness (d) was high in the study stations; stations 1, 2 and 3 were higher than stations 4 and 5.Wet season count for desmids was higher than that of dry season (1796 orgs/ml to 723orgs/ml). Closterium lunula (508org/ml) was more dominant in the wet season while Micraterias foliaceae was dominant in the dry season (Table 3).

Desmid counts decreased towards the brackish environment (Table 1)Closterium and Micrasterias genera recorded the highest number of individuals in the study followed by Cosmarium. Few species of desmids are represented in stations 4 and 5 while stations 1, 2 and 3 recorded more desmids (Fig 1).Species abundance was more in stations 1, 2 and 3 (Table 2). Species diversity (H), was high in station 1 to station 4, with the highest being station 3. Species diversity was lowest in station 5. Dominance (C) and evenness (E) were low in the study stations. Species richness (d) was high in the study stations; stations 1, 2 and 3 were higher than stations 4 and 5.Wet season count for desmids was higher than that of dry season (1796 orgs/ml to 723orgs/ml). Closterium lunula (508org/ml) was more dominant in the wet season while Micraterias foliaceae was dominant in the dry season (Table 3).  | Figure 1. Abundance of desmids genera in study stations |

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- The genus Closterium recorded the highest number of taxa (13) followed by Micrasterias, Cosmarium (9 each) and Pleurotaenium (7). Comparatively, the desmids composition of Osse River is higher than that of Ikpoba Reservoir[33], but lower than the desmids compositions of Lekki lagoon[3] and Warri/Forcados Estuaries[37] Results (Table 1), show that desmids count was low in the brackish environment (station 1 to 3 with a total of 107 species - 85%) compared to freshwater environment (Station 4 and 5 with a total of 19 species – 15%). This may be attributed to the fact that desmids are typically freshwater algae, characterized by acidic and poor nutrient environment [43, 44] which accounts for their low representation in the brackish environment in this study.High diversity of desmid species observed in this study represents a situation where many of the individuals do not belong to the same species. Low evenness observed is as a result of the fact that all the desmid species are not equally abundant. Low Simpson dominance index signifies that there is the low probability that two desmid individuals drawn at random from the population belong to the same species. This resulted in the higher diversity indices observed in the study, as the higher the dominance index the lower the Shannon diversity[45]. High species richness (d) observed is as a result of the reflection of the relationship between the number of species and the total number of individuals observed in the study stations.A close look at our report and literature from other countries show that desmids occur in higher counts in West Africa compared to other regions. This is in line with the findings of[46] who reported that there is high diversity of desmids in West Africa and attributed it to the high amount of rainfall prevalent in the region. This is supported by the high rainfall value recorded for the study area and the higher counts of desmids in the wet season than dry season. In this study, true desmids were represented mainly by the genera, Closterium, Cosmarium and Micrasterias. Desmidium, Pleurotaenium and Euastrum were also fairly represented. The false desmids were represented by Hyalotheca dissiliens. The findings of this study accord well with those of other investigators who have equally reported high desmids in their study[3, 30, 37, 46 and 44].

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML