-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Internet of Things

2016; 5(1): 29-36

doi:10.5923/j.ijit.20160501.04

Web 2.0 Tools and the Development of Cooperative Learning and Higher Order Thinking in the Saudi Higher Education Institutions

Fahad Mohammed Alblehai1, 2, Irfan Naufal Umar1

1Centre for Instructional Technology and Multimedia, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

2King Saud University

Correspondence to: Fahad Mohammed Alblehai, Centre for Instructional Technology and Multimedia, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In Saudi universities, teaching is mostly conducted based on a teacher-centered method, which deprives students of the opportunity to communicate with their instructors or create their own group. This situation, in turn, is believed to affect the students’ learning characteristics toward the course. We examined the potential of Web 2.0 tools in promoting students’ reflective thinking, knowledge sharing, interaction, and flexibility and its effect on students’ characteristics and instructor’s characteristics in learning. It also examines the effect of Web 2.0 on the development of students’ higher-order thinking skills and cooperative learning. A total of 207 cleaned questionnaires were returned from 220 respondents. The result showed that factors related to reflective thinking, knowledge sharing, interactivity, flexibility positively affected the factors of students’ and instructor’s characteristics, and such positive effect, in turn, induced a positive effect on the factors related to students’ cooperative learning and higher-order thinking. Cooperative learning factors also influenced the development of students’ higher-order thinking. Web 2.0 tools has the potential to play a key role in the development of higher order thinking in King Saud University as they allow them to interact, reflect and provide quality responses.

Keywords: Lifelong learning, Web 2.0, Higher education, Higher order thinking

Cite this paper: Fahad Mohammed Alblehai, Irfan Naufal Umar, Web 2.0 Tools and the Development of Cooperative Learning and Higher Order Thinking in the Saudi Higher Education Institutions, International Journal of Internet of Things, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 29-36. doi: 10.5923/j.ijit.20160501.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The current use of alternative tools for fostering learning is necessary to help learners solve problems and complete sophisticated tasks related to learning. Thus, collaborative learning is highly valued in the educational environment [1]. To provide a collaborative learning environment among learners, the major aspects associated with student behaviors that can be experienced through online learning tools must be identified. Furthermore, the aim of providing a sustainable learning environment for sharing knowledge has become the principal priority of higher education in Saudi Arabia, which is believed to undergo fundamental changes in the performance of teaching and learning [2]. These changes may ensue because universities and colleges respond to different trends related to global, social, technological, and learning research. Thus, the focus of higher education environment is to provide sufficient access to more content in digital formats. This priority is reflected on the current use of web-based technologies, particularly Web 2.0 tools and services, which has increased the interest of the new generation of learners [3]. Web 2.0 technologies include blog, wiki, podcast, social bookmark, tags, really simple syndication, and social network software. These technologies have the features of social interaction and collaboration to facilitate knowledge sharing and exchange over the Internet platform [4, 5]. They allow their communities to publish and share content by themselves and edit content collaboratively and interactively. Through social interaction and collective intelligence, knowledge is created, exchanged, shared, and created. Several researchers [i.e., Zohar, et al. [6]] show that the theories and beliefs adopted by teachers significantly affect their mode of teaching [7, 8]. Thus, the belief that achieving goals related to the requirements of higher-order thinking depends on the participation of both the students and the instructor in collaborative learning tasks. The major process involved in collaborative learning depends on grouping and pairing students to attain an academic goal. Cooperative learning activities are identified as an instructional method in which different students at various performance levels work together in small groups to achieve a common goal [9]. The students are responsible for one another’s learning as well as their own. Thus, the success of one student who helps other students succeed can promote the development of thinking skills. The proponents of collaborative learning assert that the active exchange of ideas within small groups not only increases the interest among the participants but also promotes critical thinking. The shared learning provides students with an opportunity to engage in discussion and take responsibility for their own learning, thus becoming critical thinkers (Totten, Sills, Digby, & Russ, 1991). Despite these advantages, previous and present studies on collaborative learning have disregarded the current individual’s characteristics associated with the learning activities with the learning tools. Empirical evidence on how the characteristics of students and instructors drive collaborative learning for developed thinking skills in the online environment remains limited. However, noncompetitive and collaborative group work in Saudi universities [10] is highly needed. Furthermore, the majority of studies on collaborative learning have been conducted in non-technical disciplines. The advances in technology and changes in the organizational infrastructure have increased the emphasis on teamwork within the workforce. Thus, developing and enhancing critical thinking skills through collaborative learning is one of the primary goals for the current study. This study was designed to examine the effectiveness of collaborative learning as it relates to the development of thinking skills at the college level.This paper investigated the effect of Web 2.0 on the development of higher-order thinking skills and group collaborative activities among Saudi university students. This work adopts reflecting thinking, knowledge sharing, interaction, and flexibility as part of cognitive constructivism beliefs.

2. Theoretical Framework

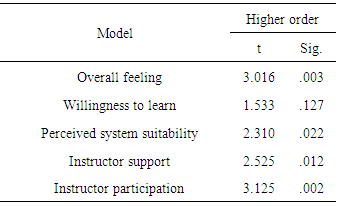

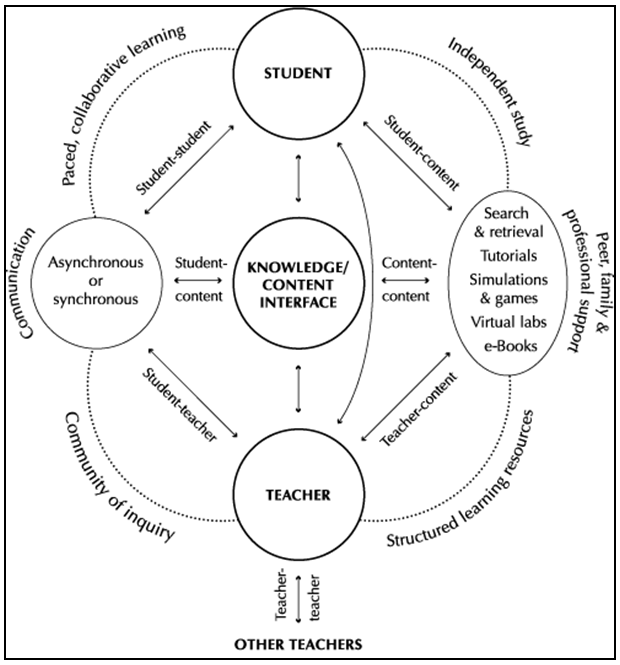

- The conditions necessary for the success of higher-order thinking and collaborative learning must be thoroughly investigated. The beliefs of learners and teachers are crucial factors in determining the effect of any educational endeavor. Thus, examining such beliefs in the context of knowledge contribution and sharing is crucial. The individual or learner is mostly accountable for sharing knowledge [11]. Vuorinen et al. (2000) have indicated that individual interaction becomes prominent only when the performance of individual is assessed and the benefits are returned to the group that performs definite learning activities.The process for developing higher-level thinking skills (Limbach and Waugh [12] and activity theory (Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy [13] are employed to construct the present research framework along with cognitive constructivist theory. Higher-order thinking pertains to thinking that typically occurs “in the higher levels of the hierarchy of cognitive processing that focus on the main aspects of the cognitive constructivist belief” [12]; p. 23). Meanwhile, activity theory focuses on the broader social and cultural context of human activity, thereby providing a comprehensive explanation of social interactions and relationships.Lytras and de Pablos [5] argued that adapting various teaching theories and concepts in a real environment and learning through social interaction (i.e., wiki) would help promote the reflective thinking of the learner to experience, conceptualize, apply, and create new knowledge to solve problems. Activity theory is one of these concepts involving the interaction between individual activity and consciousness within its relevant environmental context. Individual activities are typically driven by certain needs in which individuals desire to fulfill specific purposes. An activity is undertaken by a subject (individual or subgroup) using tools to achieve an object (objective), thus transforming objects into outcomes [14]. The weight that the critical success factors process to effectively utilize online tools within a university setting can be grouped into instructor and student characteristic processes for successful use associated with technology and support.The instructor’s role in forming the online learning activities could include the effectiveness and success of e-learning-based courses. Willis [15] as well as Moore and Kearsley [16] acknowledged that the instructional implementation of technology primarily facilitated the effectiveness of e-learning. Webster and Hackley [17] developed three characteristics related to instructor participation in effective e-learning, namely, information and communication technology (ICT) competency, teaching style, and attitude and mindset. Volery and Lord [18] suggested that instructors must provide various forms of office hours and contact methods with students. Instructors must adopt an interactive teaching style and encourage student–student interaction. Furthermore, instructors must exert good control over ICT and cultivate their ability to perform basic troubleshooting tasks.In addition, university students should be considered in terms of processing higher demands for learning in e-learning-based courses [19]. Students must process knowledge to manage learning-related tasks along with their computer skills. Beyth-Marom, et al. [20] stated that e-learning-based courses compared favorably with traditional learning, and that e-learning students performed as effectively as or better than traditional learning students. This result indicates that students prefer to use e-learning if it facilitates their learning and allows them to learn any time anywhere in their own way [21]. Engeström [22] argued that applying Web 2.0 tools based on activity theory would promote the reflection of good communication and thinking based on the dominant mode of interaction and social production. This approach would also help learners arrange their ideas and mode of thinking, which may increase individual achievements among the group while learning.Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development and scaffolding is the key concept for stating the learners’ ability to achieve learning goals with the assistance of others (social interaction), which may be more indicative of their mental development than what they can do alone (Vygotsky, 1980). Mental development occurs while learning in Web 2.0. Thus, the researcher referred to online learning theory by Anderson [23] to demonstrate the interaction between learners and a teacher in the online environment and how the resulting interaction affects communication, as shown in Figure 1. Anderson’s model illustrates how learners can interact directly with the content that they find in multiple formats, particularly on the web. However, several learners prefer to have their learning sequenced, directed, and evaluated with the assistance of a teacher. This interaction can transpire within a community of inquiry using various synchronous and asynchronous activities (i.e., video, audio, computer conferencing, chats, and virtual world interaction). These environments are mostly rich and allow the learning of social skills, collaborative learning of content, and development of individual relationships among other participants.

| Figure 1. Model of online learning showing the types of interaction (Anderson [23] |

| Figure 2. Conceptual Framework |

3. Method

- This study examined the perceptions of Saudi university students regarding the effect of Web 2.0 on the development of their higher-order thinking skills and group collaborative activities. It focused on reflective thinking, individual interaction, knowledge sharing, and flexibility as part of cognitive constructivism beliefs. Thus, quantitative method was used in collecting the data. The quantitative method involved the use of questionnaire.

3.1. Sample and Procedure

- 241 structured questionnaires were randomly distributed to the respondents who are studying at the King Saud University. The researcher contacted seven classes in the Teacher’s College, King Saud University in Saudi Arabia. Each class consisted of 40–60 students. The researcher informed the instructor of the classes about the nature of the study and their role in facilitating the researcher’s work by explaining and ensuring student participation. An email was sent to the instructors to inform them about the researcher’s visit. The researcher provided the students with a 15-minute explanation of the purpose of the study regarding the use of Web 2.0 tools available on the official Learning Management System (LMS) used in the university. Moreover, the students’ emails were obtained so that the questionnaires could be sent to them. Before the semester ended, the researcher distributed the questionnaire to the students by email in case some preferred to spend a longer time answering the questions. The researcher gave the students one hour to respond to the questionnaire. Finally, the students’ logs activities on the Web 2.0 tools in the LMS were recorded to ensure their active participation.

3.2. Instrument

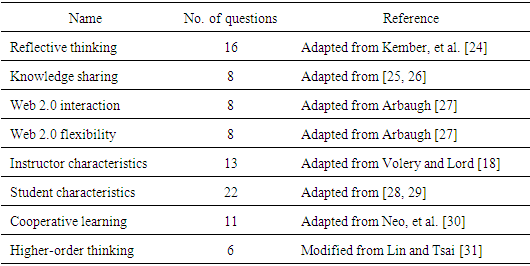

- The questionnaire was screened in a pretest, which was administered in King Saud University, to check the structure of the questions and understanding of the target respondents. Changes were made to the original questionnaire based on the comments and suggestions of the researcher.

|

4. Results

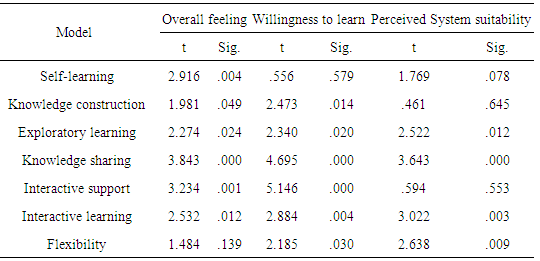

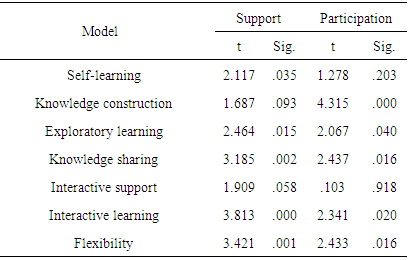

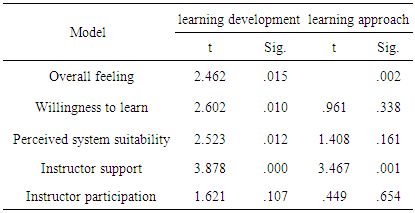

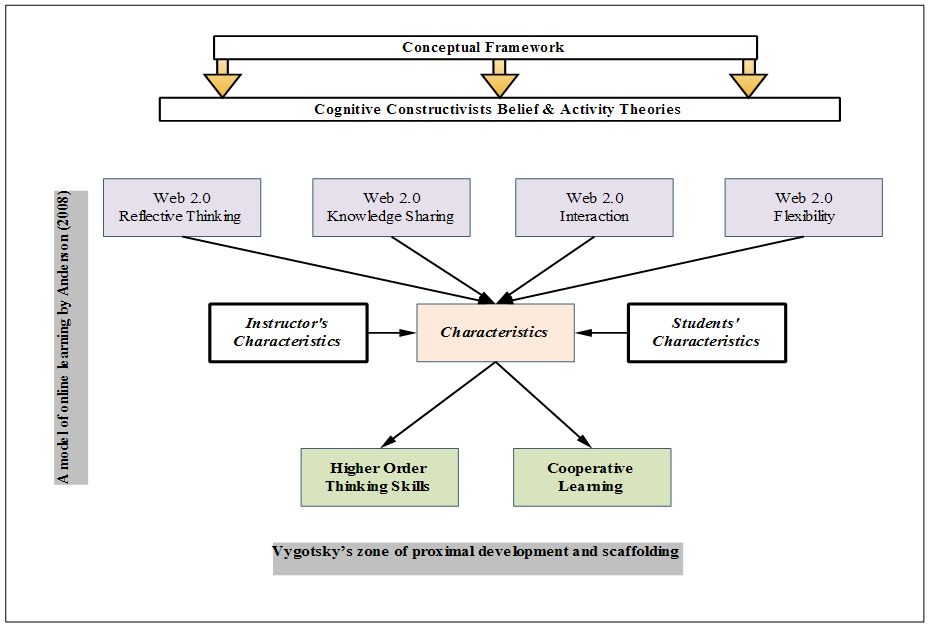

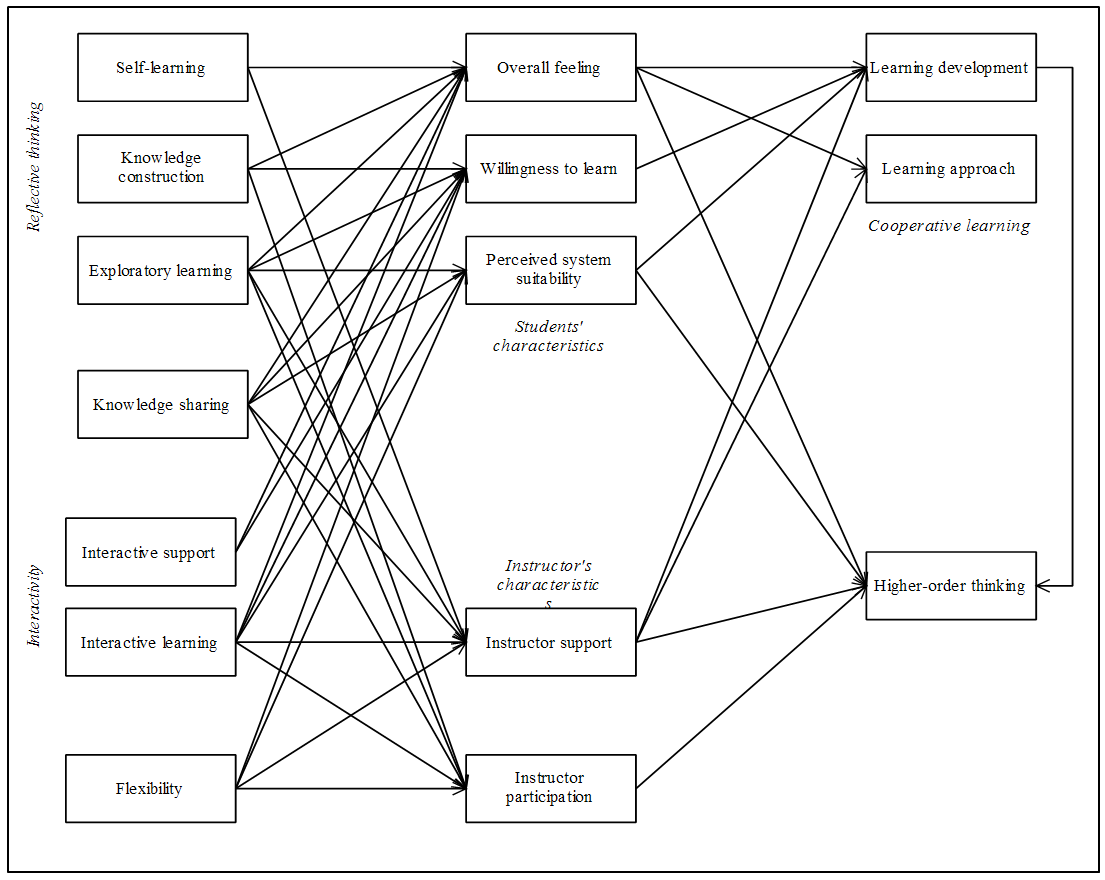

- The researcher performed multiple regression analysis by examining reflective thinking (in terms of self-learning, knowledge construction, and exploratory learning), knowledge sharing, interactivity (in terms of interactive support and interactive learning), flexibility, students’ characteristics (in terms of willingness to learn, perceived system suitability, and overall feeling), instructor’s characteristics (in terms of instructor support and instructor participation), cooperative learning (in terms of learning development and learning approach), and higher-order thinking.What are the effects of reflective thinking, knowledge sharing, interaction, and flexibility in using Web 2.0 tools on students’ characteristics?On the basis of the factor analysis results, the first dependent variable (i.e., the students’ characteristics) consisted of three factors, namely, overall feeling, willingness to learn, and perceived system suitability. In the factor analysis for reflective thinking, three factors emerged, namely, self-learning, knowledge construction, and exploratory learning. The factor analysis for knowledge sharing resulted in only one factor. Factor analysis was also conducted to identify the factors that affected interaction. Two factors emerged in this analysis, namely, interactive support and interactive learning. For system flexibility variable, only one factor was identified in the factor analysis. The results shown in Table 2 indicated that reflective thinking in terms of self-learning, knowledge construction, and exploratory learning had a significant effect on students’ learning with Web 2.0. Students’ characteristics emerged in three sub-factors, i.e., overall feeling, willingness to learn and perceived systems suitability.

|

|

|

| Figure 3. Finalized model |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Previous studies, such as the work of Giancarlo and Facione [32], acknowledge that reflective thinking is related to the cognitive skills of an individual and can be enriched with the use of more comprehensive tools. With this concept in mind, students at King Saud University claim that the use of most Web 2.0 tools promotes their knowledge through the development of a characterological component. Such characterological component is often referred to as disposition, which describes a person’s inclination to use critical thinking when faced with problems to solve, ideas to evaluate, or decisions to make. In addition, the results obtained in this study concur with those of some previous studies, such as that of Bullen [33], who showed how online learning can offer learners opportunities to share and retrieve information in a certain context. In addition, the researcher also found that knowledge sharing affect perceived system suitability. This can be reasoned to that Web 2.0 tools helped students to share their knowledge that resulted in building opportunities for its members to share their experiences along with the integration and collection of shared knowledge into their learning needs. This in return has driven the students to perceive Web2.0 tools to be suitable.Masud and Huang [34] acknowledged that providing personalized learning functionalities, such as e-annotation and bookmarks, content searching, and learning process tracking, could reinforce student learning and willingness to use such system functionalities in the future. According to Hart [35], the flexibility of an online course is very attractive to students attempting to balance work and use of online tools. Some studies also assume that teachers may fail to establish necessary channels to help students construct effective knowledge based on their teaching and their actual practices [36, 37]. The findings of the present study concur with those of other previous studies, such as that of Collin, et al. [38], who stated that reflective thinking from certain practices has the potential to promote instructors’ willingness to support learning practices. This is important in that unlike several previous studies that treat teachers’ support and participation in online learning environment as one holistic activity, this study discovers that they are governed by the motivation of factors belongs to students’ reflective thinking, knowledge sharing, system interactivity, and system flexibility. These findings carry a serious message to the decision makers in King Saud University to consider more efforts to advance the utilization of interactive learning approaches and materials necessary to develop students and instructors characteristics.Furthermore, the students’ overall feeling and perceived system suitability are the major drivers of the learning approach development of students. Thus, engaging students in cooperative learning activities can significantly impact their overall feeling about ELM. Such aspect was highlighted by AbuSeileek [39] that blinding students’ identities may be helpful in developing students’ learning approach in computer-based environments by enabling them to effectively use the available tools to create a cooperative group work in an online context.The findings of Bhuasiri, et al. [40] are aligned with those of the present study on the potential effects of instructor’s characteristics in terms of providing support on students learning performance. The results also extend the view of Razon, et al. [41] on how instructor- related factors (such as support, involvement, and interaction) can improve students’ achievement when using e-learning. However, the students’ perception of instructor’s participation has no effect on their learning development and learning approach.Akyol and Garrison [42] explored the conditions under which deep learning emerges in an online collaborative environment, where improved levels of critical thinking and learning are dependent on the perception of learners to learn and interact with the activity. This result is supported by some scholars, such as Yang [43], who demonstrated how blended learning can improve teacher scaffolding and orchestration and facilitate the provision of learning aids, as well as how collaboration can empower vocational learners with improved higher-order thinking and advanced academic achievement. The results of the current study indicate that students in King Saud University found that ELM can provide the context for teachers to support and participate in active learning activities. In the study of Wenglinsky [44], the effects of classroom practices coupled with other teacher characteristics are comparable to those of student background in terms of degree, suggesting that teachers can contribute as much to student learning as the students themselves.Yang and Wu [45] revealed how students developed their own learning strategies to support their learning through online activities. The findings of this study supported those of Khan and Masood [46], who found that cooperative learning strategies using multimedia affected students’ higher-order thinking.After all, Web2.0 tools has the potential to play a key role in the development of higher order thinking in King Saud University as it is based on asynchronous dialogue and multimedia based interaction that allows reflection and composition of thoughtful responses. Dialogue use are fundamental to higher order cognition, and the processes of articulation and sharing of ideas assist conceptualization. To ensure that Web2.0 tools are supportive of higher order thinking skills, the learning environment must be designed to so that it provides rooms for knowledge sharing, reflective thinking, interactivity, and flexibility. With this in mind, the present study investigated how current utilization of Web2.0 tools impact students’ reflective thinking, knowledge sharing, interactivity, and flexibility on their characteristics and how it drives the development of their cooperative learning and higher order thinking skills.

References

| [1] | B. Barron, "Achieving coordination in collaborative problem-solving groups," The Journal of the Learning Sciences, vol. 9, pp. 403-436, 2000. |

| [2] | M. Alamri, "Higher Education in Saudi Arabia," Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice, vol. 11, 2011. |

| [3] | L. Bryant, "Emerging trends in social software for education," Emerging technologies for learning, vol. 2, pp. 9-187, 2007. |

| [4] | A. Lau and E. Tsui, "Knowledge management perspective on e-learning effectiveness," Knowledge-Based Systems, vol. 22, pp. 324-325, 2009. |

| [5] | M. D. Lytras and P. O. de Pablos, Social web evolution: integrating semantic applications and Web 2.0 technologies: Information Science Reference, 2009. |

| [6] | A. Zohar, A. Degani, and E. Vaaknin, "Teachers' beliefs about low-achieving students and higher order thinking," Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 17, pp. 469-485, 2001. |

| [7] | N. W. Brickhouse, "Teachers' beliefs about the nature of science and their relationship to classroom practice," Journal of teacher education, vol. 41, pp. 53-62, 1990. |

| [8] | C. C. Tsai, "Nested epistemologies: science teachers' beliefs of teaching, learning and science," International journal of science education, vol. 24, pp. 771-783, 2002. |

| [9] | A. A. Gokhale, "Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking," Journal of Technology Education, vol. 7, pp. 12-19, 1995. |

| [10] | G. Tumulty, "Professional development of nursing in Saudi Arabia," Journal of Nursing Scholarship, vol. 33, pp. 285-290, 2001. |

| [11] | R. Vuorinen, M. T. Tarkka, and R. Meretoja, "Peer evaluation in nurses’ professional development: a pilot study to investigate the issues," Journal of Clinical Nursing, vol. 9, pp. 273-281, 2000. |

| [12] | B. Limbach and W. Waugh, "Developing higher level thinking," Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, vol. 3, 2010. |

| [13] | D. H. Jonassen and L. Rohrer-Murphy, "Activity theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environments," Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 47, pp. 61-79, 1999. |

| [14] | L. Uden, P. J. Valderas Aranda, and O. Pastor, "An activity-theory-based model to analyse Web application requirements," Information research, vol. 13, p. 1, 2008. |

| [15] | B. Willis, "Enhancing faculty effectiveness in distance education," Distance education: Strategies and tools, pp. 277-290, 1994. |

| [16] | M. G. Moore and G. Kearsley, Distance education: A systems view of online learning: Cengage Learning, 2011. |

| [17] | J. Webster and P. Hackley, "Teaching effectiveness in technology-mediated distance learning," Academy of management journal, vol. 40, pp. 1282-1309, 1997. |

| [18] | T. Volery and D. Lord, "Critical success factors in online education," International Journal of Educational Management, vol. 14, pp. 216-223, 2000. |

| [19] | D. R. Garrison and H. Kanuka, "Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education," The internet and higher education, vol. 7, pp. 95-105, 2004. |

| [20] | R. Beyth-Marom, E. Chajut, S. Roccas, and L. Sagiv, "Internet-assisted versus traditional distance learning environments: factors affecting students’ preferences," Computers & Education, vol. 41, pp. 65-76, 2003. |

| [21] | R. Papp, "Critical success factors for distance learning," in Paper presented at the Americas Conference on Information Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2000. |

| [22] | Y. Engeström, "The future of activity theory: A rough draft," Learning and expanding with activity theory, pp. 303-328, 2009. |

| [23] | T. Anderson, "Towards a theory of online learning," Theory and practice of online learning, pp. 45-74, 2008. |

| [24] | D. Kember, D. Y. Leung, A. Jones, A. Y. Loke, J. McKay, K. Sinclair, et al., "Development of a questionnaire to measure the level of reflective thinking," Assessment & evaluation in higher education, vol. 25, pp. 381-395, 2000. |

| [25] | N. Bakhuisen, "Knowledge Sharing using Social Media in the Workplace" A chance to expand the organizations memory, utilize weak ties, and share tacit information?," Master, VU University Amsterdam, Department of Communication Science, 2012. |

| [26] | G. P. Rad, N. Alizadeh, N. Z. Miandashti, and H. S. Fami, "Factors influencing knowledge sharing among personnel of agricultural extension and education organization in iranian ministry of jihad-e agriculture," Journal Agriculture Science Technology,(Online), vol. 13, pp. 391-401, 2011. |

| [27] | J. B. Arbaugh, "Virtual classroom characteristics and student satisfaction with internet-based MBA courses," Journal of management education, vol. 24, pp. 32-54, 2000. |

| [28] | M. Benson Soong, H. Chuan Chan, B. Chai Chua, and K. Fong Loh, "Critical success factors for on-line course resources," Computers & Education, vol. 36, pp. 101-120, 2001. |

| [29] | H. M. Selim, "Critical success factors for e-learning acceptance: Confirmatory factor models," Computers & Education, vol. 49, pp. 396-413, 2007. |

| [30] | T.-K. Neo, M. Neo, and W. Kwok, "Engaging students in a multimedia cooperative learning environment: A Malaysian experience," Same places, different spaces. Proceedings ascilite Auckland 2009, 2009. |

| [31] | T.-J. Lin and C.-C. Tsai, "A multi-dimensional instrument for evaluating Taiwanese high school students’ science learning self-efficacy in relation to their approaches to learning science," International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, pp. 1-27, 2012. |

| [32] | C. A. Giancarlo and P. A. Facione, "A look across four years at the disposition toward critical thinking among undergraduate students," The Journal of General Education, vol. 50, pp. 29-55, 2001. |

| [33] | M. Bullen, "Participation and critical thinking in online university distance education," International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, vol. 13, pp. 1-32, 2007. |

| [34] | M. A. H. Masud and X. Huang, "An e-learning system architecture based on cloud computing," system, vol. 10, 2012. |

| [35] | C. Hart, "Factors associated with student persistence in an online program of study: A review of the literature," Journal of Interactive Online Learning, vol. 11, pp. 19-42, 2012. |

| [36] | M. Sanders and J. Moulenbelt, "Defining Critical Thinking," Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines, vol. 26, pp. 38-46, 2011. |

| [37] | S. Galea, "Reflecting reflective practice," Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 44, pp. 245-258, 2012. |

| [38] | S. Collin, T. Karsenti, and V. Komis, "Reflective practice in initial teacher training: Critiques and perspectives," Reflective practice, vol. 14, pp. 104-117, 2013. |

| [39] | A. F. Abu Seileek, "The effect of computer-assisted cooperative learning methods and group size on the EFL learners’ achievement in communication skills," Computers & Education, vol. 58, pp. 231-239, 2012. |

| [40] | W. Bhuasiri, O. Xaymoungkhoun, H. Zo, J. J. Rho, and A. P. Ciganek, "Critical success factors for e-learning in developing countries: A comparative analysis between ICT experts and faculty," Computers & Education, vol. 58, pp. 843-855, 2012. |

| [41] | S. Razon, J. Turner, T. E. Johnson, G. Arsal, and G. Tenenbaum, "Effects of a collaborative annotation method on students’ learning and learning-related motivation and affect," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 28, pp. 350-359, 2012. |

| [42] | Z. Akyol and D. R. Garrison, "Understanding cognitive presence in an online and blended community of inquiry: Assessing outcomes and processes for deep approaches to learning," British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 42, pp. 233-250, 2011. |

| [43] | Y.-T. C. Yang, "Virtual CEOs: A blended approach to digital gaming for enhancing higher order thinking and academic achievement among vocational high school students," Computers & Education, vol. 81, pp. 281-295, 2015. |

| [44] | H. Wenglinsky, "The link between teacher classroom practices and student academic performance," Education policy analysis archives, vol. 10, p. 12, 2002. |

| [45] | Y.-T. C. Yang and W.-C. I. Wu, "Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study," Computers & Education, vol. 59, pp. 339-352, 2012. |

| [46] | F. M. A. Khan and M. Masood, "The Effectiveness of an Interactive Multimedia Courseware with Cooperative Mastery Approach in Enhancing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Learning Cellular Respiration," Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 176, pp. 977-984, 2015. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML