-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Internet of Things

2012; 1(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ijit.20120101.01

Virtual Reality and Real Emotionality - the Nature of Video Chat Encounters

Aristides Emmanuel Pereira

Division of Communication and Fine Arts, University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam, 96923, USA

Correspondence to: Aristides Emmanuel Pereira, Division of Communication and Fine Arts, University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam, 96923, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper examines the interaction process between users of video chat software and its groups, focusing on how members organize their relations and interactions over web-based face-to-face encounters. Through content analysis this paper unveils the impact of the moving image in the interactions of CMC users, proving that high-speed Internet connections, together with the erosion of boundaries between real and virtual, influence the creation of strong social connections within virtual worlds where video chat prevails. Through interviews and participant observation this research work scrutinizes the applications and uses of technology as instrument to promote the creation of densely formed groups of interaction.

Keywords: Interaction, Socialization, Cyberspace, Society, Video Chat, CMC, Face-to-Face, Internet, Hyperreality

Cite this paper: Aristides Emmanuel Pereira, Virtual Reality and Real Emotionality - the Nature of Video Chat Encounters, International Journal of Internet of Things, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijit.20120101.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The social and cultural aspects of a given group are elements in continuous mutation through time because they are both cause and effect of the interaction amongst the social actors, with all the dynamics within a certain group stimulating and also being stimulated by the fluctuations in its social and cultural landscape. In this case, group is defined as the place of interaction, molded by the mutual stimulus and response among the different input created by its members – sharing the same socio-cultural niche in a specific time in history.The non-presential face-to-face interaction technologies that are already incorporated into our daily lives be considered as part of the same process. Even further, the individual and the collective assimilate this technology in a form in which different geographical locations share the same virtual environment at the same time, perceiving it as real.For those social actors, their behavior while interacting in a group and culture are connected in a reciprocal influence (Segall et al., 1999); consequently, the local changes in culture and society are connected to the quality and kind of interaction individuals carry among themselves independent of the level of virtuality of the environment. Considering ‘stage’1 as the place in which the interaction occurs among individuals (Goffman, 1959), the quality of the interaction itself can be seen as directly connected with the kind of stage used to convey the communication. Therefore, society (as well as cyberspace relations) can be seen as conceived by the interaction between individuals (Wolff, 1950) within a certain social ‘stage’, and any description or analysis of this interaction has the obligation to consider, not just physical meetings, but also the different media where this interaction processes occurs.

2. Tools of Interaction and Computer Mediated Communication (CMC)

- The types of media technology promoting communication and interaction on a daily basis are increasing in number and quality, making the observation and study of the recent CMC phenomena required to better understand the interaction processes created within its fabricated boundaries. Up to now, a diversity of research studies related to Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) has been conducted, for the most part, on email, text chats, discussion groups, and virtual communities. Some past research works have focused on undisclosed anonymity as a key factor in the communication and behavior of users of Computer Mediated Communication (CMC) when interacting in groups or individually (Lea, 1999). Most of these studies took into consideration the interaction process that occurs within chiefly text-based two-way communication channels, in which some were occurring in real time (Reymers, 1998 & Kotwica, 1998), while others would take part over a more extensive period of time – such is the case of chat software and instant messaging systems, or in a extended time frame as discussion lists, MUDs or bulletin boards (Rheingold, 1995 & Langford 1998 & Rutter 2000).Some of these CMC technologies that were born with Internet are also tools that promote the creation of broader social networks, mimicking face-to-face interaction and virtually abolishing the geographical frontiers that once were the main framework impeding such meetings to occur (Woolgar 2002). This research work is an endeavor to understand and analyze the structure and means by which a given CMC can be considered as valid as a real face-to-face interaction tool. By focusing on interviews and participant observation analysis this research works traces the behavioral characteristics and profile of video chat users, creating the backbone that can be applied to explain and better understand uses and applications of simulated face-to-face interactions in future daily life communication. More specifically, the software considered by this study promotes text, audio and video chat interaction between two or more individuals, and organizes its users into a set of groups according to their interests, ethnicity, language, and other characteristics.2 With the development of interpersonal communications via the Internet (in this case instant messaging systems and chat rooms) interest became centered in creating a medium where users can experience the simulation of face-to-face encounters in its most vivid way, creating a close experience to the real interaction process. For these users, access to broadband connections, software and hardware development, as well as the increasing media literacy among Internet users, has played a major role, and it is responsible for the inclusion of interpersonal communication technology as something that cannot be seen apart from the actual socialization process.3 CMC surrounds all of us in the form of email, online news, instant messaging systems, Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter among many others; those became part of our daily lives and are included, in some instances, as tools that serve to shape our perception of society and culture. Consequently, understanding how the interaction among individuals in cyberspace takes place is a step towards visualizing how socialization in the virtual world is reshaping the perception and understanding of interactions in the physical world.

3. Social Development and Interaction

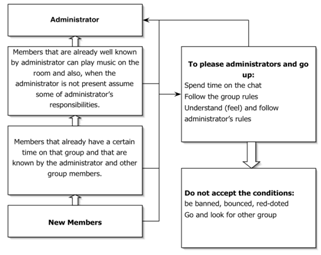

- Goffman (1959) extensively discussed the use of images and the creation of roles within a specific interaction stage4 as a key element in the human interaction process. The creation of such roles and the proper understanding of the place in which interaction happens indicate the level of social awareness that individuals have of themselves and the world around them – virtual or not. Such awareness creates a higher probability of acceptance of an individual by a given social group:‘When an actor takes on an established social role, usually he finds that a particular front has already been established for it. Whether his acquisition of the role was primarily motivated by a desire to perform the given task or by a desire to maintain the corresponding front, the actor will find he must do both.’ (Goffman, 1959, p. 27)The ‘front’ referred by Goffman is presented to an ‘actor’ by the frames in which the whole interaction happens, being more specifically the apparatus created by the medium in which the communication takes part. While working in his research Goffman often used as example face-to-face encounters in bounded and institutional contexts; however the concepts of ‘front’, ‘stage’ and ‘actors’ can be transplanted and applied to the study of the interactions within the video chat context along with a set of rules of conduct observed by each participant in the chat rooms. Thus, these sets of elements presented by Goffman are part of socially accepted constructions to the interaction. Making use of such set, video chat users understand and assume the rules and roles that are specified to them by the administrator and theme of each room – in accordance to the main subject of discussion in that room. A user that does not follow these so-called acceptable rules of behavior tends to be displaced, misunderstanding his/her role within the group. Such inadequacy leads to conflicts and the member of given video chat group faces the possibility of being bounced or, in extreme cases, banned, from that chat group.Sometimes these relations among users are strictly delineated by a hierarchical system that exists within the chat room and determines the roles or so called ‘fronts’ that the participants are supposed to assume in order to avoid conflict and to interact in harmony with other participants. This is clearly demonstrated in the conversation the researcher carried with SweetieBabeDarlin, one of the administrators of the group Love and Romance_N_the Air:‘Researcher: I will ask you something stupid, but have you ever been bounced or kicked from a chat room?SweetieBabeDarlin: yes, i have, i disagreed with an admin and they bounced me SweetieBabeDarlin: haven't been back to that room since, i don't need that kind of power trip Researcher: Do you still remember the subject of that conversation?SweetieBabeDarlin: yes, clearly Researcher: is it too much to ask you to talk about it now?SweetieBabeDarlin: she made the comment that certain people in the room weren't talking to everyone in the room, and i told her that in a room of 40 people i don't necessarily want to know everyone, too many personality differences to be able to say that i could be friends with everyone, the next thing i knew i was bounced SweetieBabeDarlin: i thought it was funny actuallyResearcher: Do you remember the name of this room?SweetieBabeDarlin: ummm let me think for a minuteSweetieBabeDarlin: i think it was Love In AustraliaSweetieBabeDarlin: or something like thatSweetieBabeDarlin: a friend invited me to itResearcher: By the way, you spoke about ‘power trip’. What kind of power an administrator has, besides bouncing people from their rooms?SweetieBabeDarlin: well, they can bounce, for whatever reason they want, they can red dot individuals, and they can red dot the whole room, they can also close the room if they choose, also a room owner can ban a person from a room Researcher: Sorry, I am not so familiar... red-dot... it means that the red-doted person will have, for some time, limitations inside the room, right?SweetieBabeDarlin: yes, a red dot takes away your ability to speak on mic, type in the text, and use your cam in the room’The dialogue with SweetieBabeDarlin shows the awareness users have of the power dynamics involved and regulating video chat rooms. It becomes obvious that there are roles that must be adhered to in order to succeed as a functional member of a given group. This understanding of roles by its members is key in the analyses of the interaction process and human relations within the structure of video chat rooms. It underlines the participant’s consciousness, and it means that users must ‘play’ certain roles within the chat room.

| Figure 1. The Power Structure Within Video Chat Rooms |

4. Self-Awareness and the Presentation of the Self

- While some groups do not allow the use of camera5 (e.g., Redeemer, Savior, Friend Group), others encourage their participants to ‘go on camera’ as much as possible; making of it a crucial part in the construction of individual identity and the management of self-presentation within most chat rooms. To illustrate this statement, video chat users seem to consider the behavior of turning the camera on and showing oneself on it as an example of wiliness to communicate. By publically addressing other members of the group, not only through voice and words but also by one’s own image, those users are making use of the principles of good and effective communication (Verberer, 2007).For instance, seven out of twenty interviewees answered that despite the fact they do not worry about their self-image, they still believe that the image shown on camera is important to attract new interactions in the video chat room. Seven other respondents answered that they are highly aware of the importance of their self-image and do worry and care about the image they present to others, considering it to be a central part of the communication process in the chat rooms. Thus, fourteen out of twenty interviewees believe that the camera use is fundamental in attracting new contacts into the room. The observation of the behavior of video chat users has shown that participants tend to browse among those chat members who have their cameras on and tend to pick up their ‘conversation partners’ based on the images that their targets present on camera, which shows that the presented image plays a big part in deciding who to interact to in their very first contact with new users. For instance, when asked about their awareness of the importance of the use of the camera while online, eleven users out of twenty replied that they tend to pick up their conversation partners based in the image they present on camera, making the choice to only start interactions with chat users that are considered attractive. The data shows that being aware of a conversation partner’s image and the front they play present through their faces is part of the video chat dynamics. It becomes evident that the self-image presented on camera by a video chat participant has a direct influence on rousing the attention of other chat users in the group. In other words, video chat users are not just interested in choosing their contacts based on the images they see, but they are also concerned with the image they show on camera, which means that they are actively choosing their conversation partners, as well as constructing their role based on the presented image and the common rules of a given chat group.Users are worried about their image on camera because they know that the image they present is fundamental in motivating others to initiate first contact. A total of fourteen interviewees said they worry about the way they present themselves to others while on camera, while twelve were interested only in chatting with good-looking people. Users are not just worried about the way other people look, but also about how they present their images to others. It is sensible then to conclude that people considered attractive and with their cameras turned on will receive more messages and first interaction tentative than people that have their cameras off and that are not as self aware of the image they present to other users. It is then, in the simulated space of chat room groups that the stereotype of real life interaction repeats itself.Such concern about roles and appearance of is part of setting up an acceptable ‘front’ in the ‘stage’ of interaction. This is a complex, multifaceted task, involving presenting an attractive image to other members of the group while being able to choosing an appealing nickname as well as showing oneself able to carry on an open conversation in the public chat room window, following the rules established by that particular ‘stage’ of interaction.Above all, users of video chat under those circumstances mentioned above seek to show an attractive and clean image on camera. Coordinated with a good understanding of their roles and the rules inside a given group, these factors tend to increase their chances of receiving and making first contacts with new users, fulfilling what can be described as the active and passive interaction with other members. In this case, the term ‘passive’ refers to the ability to attract new contacts by image and messages; the term ‘active’ is defined by the characteristics of browsing, searching and initiating new contacts based on another participant’s image and messages.

5. Roles, Interaction and Hyperreality

- As the simulation of the interaction and communication cannot be disassociated from the user’s online image, it is essential to understand the collective and individual behavior of CMC users to comprehend the particularities of interactions among individuals using video chat technology. Whereas an important part of the ‘life’ in video chat rooms is a process which simulates the relations that already exist in the ‘real world,’ where group identification and presentation of the self is based not only on text (as in earlier and parallel CMC processes), but also on the color of the skin, language, ethnical traces, and cultural representation through clothing, and other visual characteristics. In short, the video chat room, if not ‘actual’ reality, is a very close simulation (Baudrillard, 1994) of reality. This is an example of Baudrillard’s concept of ‘hyperreality’ a condition generated by technology where the ‘real’ is represented by mechanisms simulating social interactions within an ambience that is also a simulation of the social sphere, disconnected from reality itself. Such simulation within a simulation model, according to Baudrillard, results on a polarized sensation of reality. As Baudrillard writes: ‘In this passage to a space whose curvature is no longer that of the real, nor of truth, the age of simulation thus begins with a liquidation of referentials… It is no longer a question of imitation, nor of reduplication, nor even parody. It is rather a question of substituting signs of the real for the real itself.’ (Baudrillard, 1988, p.167). The ‘liquidification of referentials’ created by the virtual interaction offers a unique experience to its users, together with a shift of values. It is the substitution of signs of the real for the reality of virtual; in other words, the simulation actually becomes a powerful ‘is’, instead of an ‘as’, in the minds of its users.In this ambient of Virtual Reality and Real Virtuality, some elements, like image on camera, nickname and conversations, are instruments used to determine how members of a given chat group should perform during intra- or inter-group interactions, determining how users are able to interact among themselves with a certain kind of harmony and without creating unacceptable levels of tension or misunderstandings. Those are the ‘normative’ rules and they are part of the virtual universe that constitutes video chat environment reality, giving the reality of the virtual an amalgam that will keep its users interested in the virtual interaction process as an experience of the real.

5.1. Technology, Culture and Individual Adaptation

- The affirmation and maintenance of an individual identity is fundamental to any social interaction process. This holds true within video chat rooms as it is out in the ‘real world’. In this software’s video chat group structure, the creation of ‘identity’ is in part derived from the image is presented on camera allied to the role that an individual assumes within. The formation of this virtual-individual identity precedes the developed/projected identity, and it correlates with the formation of groups in which members apparently share the same affinities and interests. Each individual within a specific group must be aware of the technology that is used to represent their emotions, ideas and intentions. Moreover, they must possess enough media literacy skills to know how an isolated change in their media presentation affects the whole interaction.It is part of the process of understanding and making use of a set of tools that can help to improve the communication process, and coordinate the process itself to attend to individual and group interests. In joining the collective, individual users bring their own aspirations and expectations of what a virtual relationship can be or become, recreating emotionality through virtual environments. All the interactions, and individual processes involved in the creation of a virtual identity show that this ‘sociological phenomena do not exist in such isolation and recomposition, but that they are factored out of this living reality by means of an added concept, thus produces the totality of social life’ (Wolff, 1950, p.21).

5.2. The Virtual Deviant

- Even though the creation of a virtual self-identity on video chat obeys to a specific set of rules, a member of a video chat group should, more than just reproducing pre-determined roles, be aware that the technology used for his/her interaction is an instrument that can generate ‘gaps’ between the intention and the real image presented and perceived by others. When a lack of understanding of the technological instrument (in this case, video chat) becomes apparent, then the individual is unable to properly control the medium; from this point on it becomes impossible for a potential smooth interaction in between this individual and other members of the group. This user becomes within this particular environment of interaction someone to be avoided – a matter which refers back to the ‘presentation of the self’ (Goffman, 1971), and it clearly applies to the ‘stage’ of the video chat room.This inadequate individual is then seen as non-acceptable from the perspective of other group members – to use another word from Goffman (1971), he or she develops a ‘stigma’ among the members of that specific community or group. We might also refer to this user by the term ‘virtual deviant’ suffering from temporary and local ‘virtual deviance’: the inadequacy of an individual to behave in certain pre-established patterns of socialization and interaction within a given social structure. The same definition can also be applied to any level of any given virtual community in which its members engage on high-level socialization process6. Notice that the level of literacy of the medium in which the interaction process occurs is not the only factor that contributes to optimizing the relations within a virtual community, yet, it directly influences the perception and understanding of its participants involved in that particular CMC process.Nevertheless, the level of media literacy an individual can acquire with respect to a specific Computer Mediated Communication tool is directly associated to his or her capacity to understand and use the tool itself. Tech-savvy users have a bigger change to create an efficient communication process within the chat group that is less susceptible to misunderstandings created by the improper use of technology; nevertheless they also should be able to understand the social requirements created by the particular medium. The level of comfort and self-confidence that an individual shows in regard to a particular CMC tool and its inherent communication process is also translated into this so-called ‘technological adequacy’.

6. The Paradox of Globalization

- Although it was not the intent of this research work to find any trace of cultural aspects being linked to computer and technology literacy, it is reasonable to assume that cultural values may contribute to the creation of ‘virtual’ communities and niches of cultural resistance within cyberspace. For instance, considering the analyzed software, some of the groups are organized by language, religion, geographical location and ethnicity (e.g., Islamic Groups, Afro-American Groups, etc). In these cases, the individuals transpose their cultural values and identification to the new media, learning how to deal with the differences in transmitting meaningful information through the given CMC tool. This can be addressed as media migration, with users transposing cultural characteristics from real life to the ‘virtual’ world.The chat rooms also offer a level of specialization to meet the demands of very specific and interest-centered groups. Even the banners that appear as advertisements in the upper part of the main chat window, or as ‘pop-up’ windows, follow a certain pattern to adapt their language and approach to the title and the subject of a given group. Among the numerous advertisement pages that can be seen in the freeware version of the software (the paid version excludes advertisement), one in particular should be mentioned. The banner that appears as an ad is an example of the many advertisement pages that circulate among Islamic-oriented groups. The ad mimics the alliteration of the famous ‘Intel Inside’ slogan and uses the same logotype used by the Intel Corporation to create the slogan ‘Islam Inside’ (Figure 2). This is an interesting example of how advertisements can be audience oriented and provide an insight on how demographics and data mining is a key characteristic of traditional and non-traditional media industries.

| Figure 2. Islam Inside - The play of words and logo mimicking Intel’s motto defines the cultural identifier of the group “Islam Inside” |

7. Conclusions

- Video chat as a Computer Mediated Communication process is not only special by its particular characteristic of mimicking real life – in the shape of face-to-face interactions –, but also by the dependency that its users have presented towards the medium and the connectivity to other users. For instance, as the research shows, fourteen out of twenty interviewees have said they keep in touch with their contacts on a daily basis, while six other respondents said they talk at least once a day with their partners, with the majority of the respondents reporting spending two or more hours in video chat interactions. Such information proves that video chat users have a tendency to allocate a specific part of their online time exclusively to video chat activity; with broadband Internet as the backbone to keep the social life of many of those exchanges. Consequently, the quality of interactions plus the amount of time spent online interacting to other users can be used to classify those interactions not as casual but rather as steady relationships.The emotionality of these interactions inside video chat rooms has revealed to be a fundamental factor – together with time – to create meaningful connections among video chat users. Those can be mainly divided in two groups, the ones that experience negative emotions when deprived from their interactions with their online contacts (thirteen respondents), and those that do not seem to care (seven respondents), indicating that video chat users can be separated in two categories:1. Highly Emotionally Connected 2. Detached Highly Emotionally Connected are the users who are not influenced by the technicalities of the medium, making use of it without being disturbed by technical problems, making use of the medium and absorbing the interaction in its totality – not second guessing the nature of it as a product of a ‘artificial setting’. Detached users often consider the technicalities of the medium as a barrier for the proper development of the communication, perceiving the medium as detached from reality and as a virtual environment that cannot be validated through the emotional outcomes that it may generate. Those were the users that also responded to “not care” if their conversation partners had their faces available on camera – pointing to a low level of interest as well as to low levels of intimacy in the interactions. These two extremes show that the element of video is fundamental part in the creation of more emotional and intimate connections among video chat users, and that the moving image of a chat session counterpart is an important factor in increasing the emotional perception of the whole interaction process, making users perceive the interaction itself as an extension of their personal lives (McLuhan, 1964).As a result, video chat participants do not make any special distinction in the way technology influences the quality of their real or virtual relations, with users just considering the emotional outcome they receive from it. This concurs to the findings presented by Kotwica (1998) in her study the perception of members of Virtual Communities (VC) have of their interactions while online. According to Kotwica’s quantitative research work, 70% of 230 CMC users thought that a virtual community ‘is a real community’, nevertheless its online quality. Additionally, 86% of the respondents recognized virtual communities as extensions of the relationships they have in the real world. It appears that the understanding of virtual communities as extensions of the real is based in the same perception that video chat users have – that they are not building a different reality but rather expanding the influence and boundaries of their social networks. Kotwica’s survey also demonstrates that most part of the respondents felt that some kind of face-to-face interaction was fundamental in helping to form a ‘more complex relationship’ inside the virtual communities, validating the argument of this present research work in which CMC users often see video chat interactions as a mechanism by which virtual communities can be constructed in such a way that they can ‘feel’ as extensions of the real.These findings show that video chat can be applied in diverse situations in which actual face-to-face interactions are essential but should be avoided or cannot happen in the ‘physical’ world; such as in the treatment and assessment of patients suffering from psychological or mental conditions, as well as corporate meetings, interviews and the assessment of candidates for job positions when geographical or physical barriers are present. Social networking websites such as Facebook and Myspace might also use video chat to revamp the way users see and interact with their virtual communities, increasing the levels of intimacy and interactivity by the use of video and audio (the technology offers numerous applications in for socialization and treatment of medical conditions such as panic attacks, agoraphobia and depression). In conclusion, video chat and the relationships that users carry on within its groups appear to be more as an extension of the real social ambience rather than a totally new and re-created reality. Supporting that ‘all media are fragments of ourselves extended to the public domain, the action upon us of any one medium tends to bring the other senses into play in a new relationship’, (McLuhan, 1964 p.234) shaping a new fashion of social networking that reflects with more intensity the ‘real’ daily life experiences.

Notes

- 1. Goffman uses the term stage in a reference to theater, where the main action of the play takes part and communicates to the audience through the so-called ‘fourth wall’.2. The software used in this research work can be downloaded free of charge from http://www.paltalk.com As the researcher was unable to contact the company, the researcher reserves the right to make no citations of the software directly in this research work (both the address and the phone and fax numbers available at the company’s Whois information screen were invalid at the time of this work). 3. Note that this technological insertion does not occur equally in all levels of our society and our world. It is fundamental to understand that, for some parts of it, even access to a telephone is still limited.4. Here, Goffman’s term ‘stage’ has the same meaning as ‘place’.5. In the same way the camera is key element in the construction of the public self in most chat rooms, some groups take it as a secondary element that would only disrupt the collective directives of the group. Those are mainly religious groups where preaching is the main communication tool (in those cases the camera would only act as a disruptive element, taking the audience’s attention from the homily).6. High socialization occurs when members of the same CMC tool are intrinsically involved in their interactions through the use of sound, image and text.7. One may affirm that the same happens with the extremist and right wing groups in Europe and in the United States.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML