-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Information Science

p-ISSN: 2163-1921 e-ISSN: 2163-193X

2025; 14(1): 1-10

doi:10.5923/j.ijis.20251401.01

Received: Mar. 5, 2025; Accepted: Mar. 26, 2025; Published: Mar. 28, 2025

Enhancing Innovation through University-Industry Research Partnerships in Tanzania

Goodluck Asobenie Kandonga

Department of Library, Information and Archives, Shanghai University, No. 99 Shangda Road, BaoShan District, Shanghai, China

Correspondence to: Goodluck Asobenie Kandonga, Department of Library, Information and Archives, Shanghai University, No. 99 Shangda Road, BaoShan District, Shanghai, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

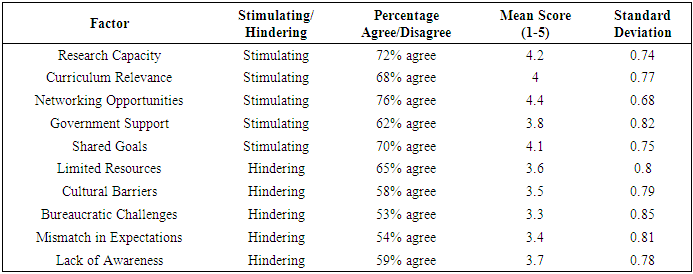

Industry–university research collaborations have gained significant global attention for their critical role in fostering innovation and economic growth. This study examined the enhancing innovation through university–industry research partnerships in Tanzania, highlighting their impact on knowledge transfer, technology commercialization, and workforce development. The findings reveal key stimulants, including networking opportunities (76% agreement, Mean: 4.4, SD: 0.68), research capacity (72% agreement, Mean: 4.2, SD: 0.74), and shared goals (70% agreement, Mean: 4.1, SD: 0.75), underscoring the importance of strong networks, robust research infrastructure, and aligned objectives between academia and industry. However, challenges such as limited resources (65% agreement, Mean: 3.6, SD: 0.8), cultural barriers (58% agreement, Mean: 3.5, SD: 0.79), and bureaucratic hurdles (53% agreement, Mean: 3.3, SD: 0.85) hinder the effectiveness of UIPs. Despite the existence of national policies, inadequate research funding (78% agreement) and weak implementation of university strategic plans (45% rated as moderate) continue to limit collaboration. Additionally, the study's ordinal logistic regression analysis reveals that communication, clear goals, government policies, culture, and commitment have significant positive impacts on UIP development, while trust, experience, and funding show negative correlations. These findings emphasize the need for enhanced funding, clearer policies, and stronger implementation frameworks to foster effective university-industry collaborations that drive technological innovation and economic growth in Tanzania.

Keywords: University–industry collaboration, Innovation, Research partnerships, Technology transfer, Economic development

Cite this paper: Goodluck Asobenie Kandonga, Enhancing Innovation through University-Industry Research Partnerships in Tanzania, International Journal of Information Science, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.ijis.20251401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- University-Industry Collaboration (UIC) plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between academic research and industrial innovation while producing highly skilled graduates who meet labor market demands [1]. Universities are often regarded as "growth engines" that drive national innovation by generating research outputs that enhance industrial productivity and contribute to socio-economic transformation. Collaboration between academia and industry facilitates knowledge transfer, supports technological development, and enhances the commercialization of research findings. In developed countries, UIC has proven to be one of the most effective strategies for advancing scientific research, fostering technological breakthroughs, and addressing market inefficiencies [3].The increasing significance of university-industry collaboration stems from the recognition that innovation and economic growth rely on effective knowledge transfer. While universities generate new knowledge through research, industry applies this knowledge to develop innovative products and services, creating synergies essential for technological advancement and global competitiveness [3]. Such collaboration not only stimulates job creation and entrepreneurship but also fosters regional economic development, making it a key element of national and local economic strategies [4].Innovation system theory further underscores that innovation emerges from interactions among various actors, including government agencies, research institutions, and businesses. This perspective highlights the role of national innovation systems (NIS) in promoting knowledge dissemination and collaboration through supportive policies and networks [5], [6], [7]. By fostering strong linkages between universities and industry, countries can enhance their capacity for technological progress, improve industrial competitiveness, and drive sustainable economic growth.Despite its benefits, university-industry collaboration (UIC) faces challenges due to differences in goals, structures, and timeframes between academia and industry. Universities emphasize long-term knowledge creation and dissemination, whereas industry prioritizes rapid results and profit maximization. These contrasting objectives often lead to conflicts, with universities valuing open knowledge transfer while industries seek proprietary research outcomes [8]. Successful collaboration depends on trust, prior experience, and the ability to manage cross-organizational learning [9], [10]. Empirical evidence suggests that geographic proximity, personal relationships, and institutional reputation also influence UIC effectiveness, as businesses tend to collaborate with nearby universities despite potentially suboptimal partner selection [11], [12].In developing economies, particularly in Africa, university-industry relationships remain weak due to historical, structural, and policy-related constraints. Many African universities have been criticized for being disconnected from industry needs, producing graduates whose skills do not align with labor market demands [13], [14]. This disconnect is further exacerbated by limited research funding, inadequate infrastructure, and an emphasis on theoretical rather than applied research. However, strengthening UICs in these regions holds significant potential to drive innovation, economic growth, and job creation. Addressing these challenges requires building trust, improving institutional frameworks, and promoting experiential learning and skills acquisition [15], [16]. By aligning academic research with industry needs and fostering collaboration, universities and businesses can mutually benefit while contributing to broader socio-economic development and global competitiveness [17], [18].In Tanzania, UICs are recognized as key drivers of economic development, particularly in priority sectors such as agriculture, health, and energy. The Tanzanian government has made notable efforts to strengthen these partnerships, as reflected in Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025, which emphasizes research and innovation as catalysts for sustainable economic growth [19]. Noteworthy collaborations include joint research between the University of Dar es Salaam and the Tanzania Agricultural Research Institute (TARI) to enhance agricultural productivity, as well as partnerships between the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS), the Ministry of Health, and the World Health Organization (WHO) to address public health challenges [20], [21]. Despite these advancements, the overall extent of collaboration between Tanzanian universities and industry remains limited. Many industries hesitate to invest in long-term research due to funding constraints, risk aversion, and regulatory challenges [22]. Overcoming these barriers requires a more supportive policy environment, increased investment in research and development, and stronger incentives for industry participation in academic collaborations.A major barrier to the effectiveness of industry-university-research collaboration in Tanzania is the lack of an integrated innovation ecosystem. Public universities continue to face insufficient funding for research and consultancy, which limits their ability to establish effective partnerships with industry [23]. In addition, Tanzania's bureaucratic and regulatory environment poses a major challenge to research collaboration, as lengthy approval processes and unclear guidelines hinder the smooth functioning of industry-university-research collaboration [24]. The private sector, while growing, remains largely disconnected from academia, with industry focused on short-term profitability rather than investing in research-driven innovation. As a result, Tanzanian universities perform poorly in generating internal resources through research and consultancy, reducing their overall efficiency and contribution to national development [25].Innovation should be a national priority, and universities, industry, and policymakers should work together to create an integrated system that supports knowledge generation, commercialization, and technological advancement [26]. By integrating academic research with industry needs and ensuring the university actively engages with industry stakeholders, Tanzania can leverage UIC to drive technological innovation, increase productivity, and boost economic growth.Industry-university-research collaboration in Tanzania faces unique challenges, such as limited funding, poor infrastructure, and a lack of established networks between academic institutions and industry. However, recent initiatives, such as those supported by the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH), have begun to bridge these gaps. In contrast, countries such as Kenya and South Africa have had greater success in promoting such collaborations through government policies and institutional frameworks that prioritize research commercialization and innovation ecosystems [27], [28]. The experiences of these countries highlight the potential for improving industry-university-research partnerships in Tanzania through targeted investments and policy reforms.

2. Methodology

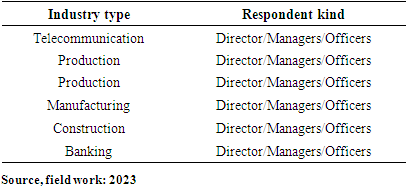

- This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the research methodology adopted for this study. It begins with an overview of the research methodology and then discusses the research design, including participant selection, data collection methods, and sampling procedures. This study used both primary and secondary data sources, using a mixed methods approach to ensure a thorough investigation. Data analysis techniques and procedures were elaborated in detail, highlighting how insights could be gained from the data collected. In addition, ethical issues were considered to ensure the integrity and credibility of the study. The choice of methodology depended on the research objectives, characteristics of the study population, and the epistemological stance adopted. By integrating quantitative and qualitative methods, this study aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study.This study was conducted in Tanzania and utilized relevant information provided by universities and industry. A combination of probability and non-probability sampling techniques, specifically simple random sampling and judgment sampling, were employed. Simple random sampling was used to ensure equal representation of respondents, while judgment sampling allowed for the selection of key participants with relevant expertise. The purpose of the study was clearly communicated to all participants and informed consent was obtained. Given that the study focused on factors influencing university-industry alliance research collaboration, both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods were employed. To collect the necessary information, three main tools were used: questionnaire, interviews, and document analysis, ensuring a comprehensive review of the subject matter.

|

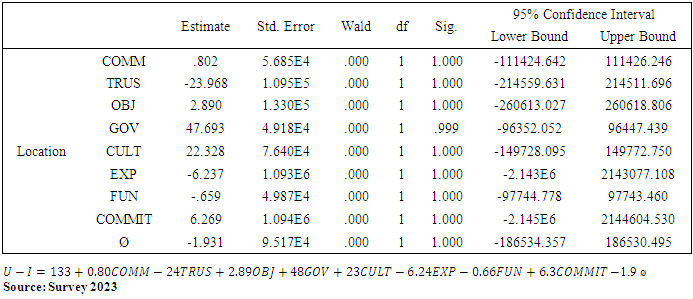

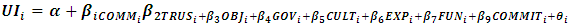

Where; H0 is the null hypothesis and H1 is the alternative hypothesis.In addition to descriptive analysis, an econometric model (that is, an ordered logit model) used to examine the relationship between universities and industry and the relationship between variables, and determine the motivator factors of university and industry research collaboration in Tanzania. By specifying the following regression model, the study used in an ordered logit model to determine which motivator factors and to what extent these factors affect the university-industry research connection.

Where; H0 is the null hypothesis and H1 is the alternative hypothesis.In addition to descriptive analysis, an econometric model (that is, an ordered logit model) used to examine the relationship between universities and industry and the relationship between variables, and determine the motivator factors of university and industry research collaboration in Tanzania. By specifying the following regression model, the study used in an ordered logit model to determine which motivator factors and to what extent these factors affect the university-industry research connection. | (1) |

is the country specific effects; i signify the university/industry; UI denotes University-Industry research collaboration, COMM denotes communication, TRUS show trust, OBJ denotes objectives and goals, GOV indicates government/regulations; CULT denotes culture; EXP denotes experiences on research collaboration; FUN imply Fund; COMMIT shows commitment and

is the country specific effects; i signify the university/industry; UI denotes University-Industry research collaboration, COMM denotes communication, TRUS show trust, OBJ denotes objectives and goals, GOV indicates government/regulations; CULT denotes culture; EXP denotes experiences on research collaboration; FUN imply Fund; COMMIT shows commitment and  is the residual term.

is the residual term.3. Results

- This chapter presents the key findings of the research, highlighting the relationship between the research questions and the actual challenges faced in Tanzania. It primarily explores the driving factors influencing university-industry research partnerships, focusing on communication, trust, objectives and goals, government regulations, culture, research collaboration experiences, and environmental factors. Based on previous studies and the conceptual model, these elements are identified as both driving forces and challenges in establishing effective university-industry relations.

3.1. Factors that Stimulate/ Hinder University Industry Partnership

- The analysis of factors that promote or hinder University-Industry Partnerships (UIPs) in Tanzania is based on quantitative data collected from stakeholders including university staff, industry professionals and policy makers. The factors were derived from survey responses and analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical techniques.

|

3.1.1. Stimulating Factors

3.1.1.1. Research Capacity and Expertise

- The study found that 72% of respondents agreed that the research capabilities of higher education institutions (HLIs) play a vital role in promoting university-industry partnerships (UIPs). With an average score of 4.2 (on a scale of 1 to 5), stakeholders expressed strong confidence in the value of university research expertise in driving these collaborations. HLIs provide cutting-edge research, innovative solutions, and highly skilled professionals, making them attractive partners for industries seeking to remain competitive and improve their technological capabilities. Their expertise goes beyond scientific knowledge to include theoretical frameworks, problem-solving approaches, and sustainable development strategies, helping industries address complex challenges and navigate global market dynamics.In addition, university partnerships enable industry to strengthen research and development (R&D) efforts while sharing the costs and risks of innovation. Access to state-of-the-art facilities, cutting-edge projects, and a well-trained talent pool accelerates industry innovation and strengthens product development. The high average score of 4.2 further reflects industry’s appreciation for universities as key drivers of progress. This is consistent with global trends that university-industry collaborations significantly boost R&D output and economic growth. The findings highlight the need for continued investment in academic research and increased collaboration between universities and industry to maximize the benefits of these partnerships for economic and technological advancement.

3.1.1.2. Curriculum Relevance

- The study found that 68% of respondents believe that aligning university courses with industry needs is critical to attracting industry collaboration, with an average score of 4.0. This alignment ensures that graduates gain relevant skills, bridging the gap between theory and practice while making universities a more attractive partner for industry. Industry-focused courses increase employability, reduce the training burden on companies, and facilitate a smoother workforce transition. By involving industry professionals in curriculum design, universities can integrate the latest trends and technologies, forming a continuous feedback loop to maintain the relevance of education. The strong positive perception reflected by a score of 4.0 highlights the industry's preference for universities that produce job-ready graduates, saving time and resources while accelerating innovation. In order to maintain and strengthen university-industry partnerships, academic institutions must continuously adapt their courses to changing market needs, ensuring mutual benefits for both academia and industry.

3.1.1.3. Networking Opportunities

- The data indicates that 76% of respondents agree that networking opportunities stimulate collaboration, with a mean score of 4.4 and a standard deviation of 0.68. This suggests a strong consensus on the importance of networking in fostering partnerships between universities and industries. Networking events, joint research projects, and professional forums provide platforms for knowledge exchange, relationship building, and the alignment of academic research with industry needs. Given that Tanzanian industries often lack structured research and development (R&D) units, effective networking acts as a bridge, helping firms tap into university expertise for innovation and problem-solving. The relatively low standard deviation (0.68) further suggests consistency in responses, indicating a widely shared perspective among stakeholders.

3.1.1.4. Government Support

- While government support is recognized as a factor in UIC, it is perceived as less stimulating compared to networking opportunities. Only 62% of respondents agree that government support fosters collaboration, with a mean score of 3.8 and a standard deviation of 0.82. This lower agreement level suggests mixed opinions on the role of government policies, funding mechanisms, and regulatory frameworks in promoting UIC. The relatively higher standard deviation (0.82) indicates greater variability in perspectives, reflecting potential concerns about bureaucratic inefficiencies, limited research funding, and regulatory challenges that hinder seamless collaboration.

3.1.1.5. Shared Goals

- The study found that 70% of respondents (with an average score of 4.1) agreed that goal alignment between universities and industry is critical for successful collaboration. Shared goals can promote mutual understanding, enhance communication, improve resource allocation, and make partnerships more effective and sustainable. When universities align their research with industry challenges, they can increase the relevance of academic work and encourage industry investment. In addition, goal alignment helps mitigate conflicts, ensuring smoother collaboration and stronger commitment from both parties. This synergy can enhance innovation, workforce readiness, and economic impact. Overall, strong consensus emphasizes the importance of shared goals in building long-term, adaptable university-industry partnerships.

3.1.2. Hindering Factors of U-I Collaboration

3.1.2.1. Limited Resources

- A majority of respondents (65%) recognize limited resources as a major barrier to effective UIC in Tanzania. The mean score of 3.6 suggests a moderate but significant impact, while the standard deviation of 0.8 indicates some variation in responses. Many universities in Tanzania face inadequate funding for research and innovation, while industries may lack the financial capacity or willingness to invest in long-term research collaborations. This limitation restricts access to necessary infrastructure, skilled personnel, and technology, weakening the foundation for sustained engagement.

3.1.2.2. Cultural Barriers

- The study found that 58% of respondents identified cultural differences between academia and industry as a significant barrier to collaboration, with an average score of 3.5. These differences stem from distinct values, priorities, and operational approaches, where academia emphasizes theoretical research and long-term goals, while industry focuses on practical applications and immediate results. This divergence can create misunderstandings about goals, timelines, and expectations, making it challenging to establish mutually beneficial collaborations. While some respondents saw these differences as manageable through better communication, others viewed them as requiring more systemic changes to foster stronger partnerships.To bridge this cultural gap, both academia and industry must invest in initiatives that promote mutual understanding and collaboration. Universities can organize joint workshops and encourage faculty engagement in industry roles, while companies can integrate academic research into their innovation processes. Additionally, embedding real-world industry challenges into academic curricula can help students develop practical skills while aligning education with market needs. The 58% agreement rate and average score of 3.5 underscore the importance of addressing cultural differences through dialogue, engagement, and shared learning opportunities to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of university-industry partnerships.

3.1.2.3. Bureaucratic Challenges

- Bureaucracy is another critical barrier, with 53% of respondents agreeing that complex administrative procedures hinder collaboration. A mean score of 3.3 indicates a moderate impact, while the standard deviation of 0.85 suggests varying experiences among respondents. Lengthy approval processes, rigid regulations, and unclear legal frameworks discourage both universities and industries from engaging in joint initiatives. Streamlining these processes through policy reforms could enhance efficiency and facilitate smoother collaboration.

3.1.2.4. Mismatch in Expectations

- The study found that 54% of respondents agreed that differing expectations between higher education institutions (HLIs) and industry can hinder effective partnerships, with a mean score of 3.4. Universities often focus on research output and academic goals, while industry prioritizes market relevance and return on investment. These misaligned expectations can lead to misunderstandings, dissatisfaction, and ineffective collaborations. Although the issue is recognized, it is not viewed as the most significant barrier compared to other challenges.To address this, clear and open communication is essential. Establishing shared goals, conducting regular check-ins, and developing formal agreements outlining roles and responsibilities can help align expectations. Training programs that foster mutual understanding between academia and industry can also strengthen partnerships. The 54% agreement rate and mean score of 3.4 highlight the need for structured communication and collaboration strategies to ensure that both sectors work effectively toward common objectives.

3.1.2.5. Lack of Awareness

- A significant 59% of respondents highlight lack of awareness as a barrier, with a mean score of 3.7 and a standard deviation of 0.78. Many industries remain unaware of the potential benefits of collaborating with universities, while academic institutions often fail to effectively communicate their research capabilities. Limited knowledge-sharing platforms and weak industry-academia linkages further exacerbate this issue. Increasing awareness through outreach programs, networking events, and public-private partnerships can foster greater engagement.

3.2. Other Factors

3.2.1. Tanzanian National Technology Transfer Policy

- The Ministry of Education, Science, Technology, and Vocational Training evolved from the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education, which existed before 2005. It was later merged under President John Magufuli’s administration, incorporating responsibilities from the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training while transferring communications to the Ministry of Works, Transportation, and Communications. The Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH), established under Parliamentary Act No. 7 of 1986, succeeded the National Research Council (UTAFITI) and serves as the primary government advisory body on scientific research, innovation, and technology transfer. COSTECH operates autonomously avoiding bureaucratic delays, and oversees various R&D institutions. Its role aligns with Tanzania’s industrialization agenda and the National Vision 2025, which aims to promote science, technology, and innovation to improve products, processes, and services for economic growth.The Science and Technology National Policy aims to strengthen collaboration between technology research institutions, the private sector, and the public sector to encourage demand-driven research, develop national scientific capabilities, and support skilled talent. However, research findings suggest that the policy emphasizes technological adaptation rather than technological innovation, which limits its effectiveness in fostering university-industry partnerships. Additionally, the mechanisms for industrial collaboration remain poorly defined, and the policy primarily relies on foreign direct investment (FDI) for technology transfer rather than strengthening national university-industry links. As a result, the policy's implementation has been weak, with limited noticeable impact on fostering stronger research-industry relationships at the national level.

3.2.2. Intellectual Property Right Policy

- Intellectual property (IP) refers to the legal ownership that results from intellectual activity in various fields such as industrial, scientific, and artistic domains. It plays a crucial role in protecting the moral and economic rights of creators while promoting creativity, the dissemination of knowledge, and fair trade, which contributes to economic and social development. Patents, in particular, facilitate the flow of knowledge between universities, research centers, and industries. Intellectual property rights allow creators and inventors to temporarily monopolize their creations, ensuring that their work is rewarded. These rights encompass various forms, including trademarks, patents, copyrights, and industrial designs. Tanzania's history with IP dates back to the colonial era, with the introduction of patent and copyright legislation in the 1920s, and continued development through various international treaties and conventions such as the WIPO Convention and the Patent Cooperation Treaty.Despite the legal framework surrounding intellectual property, there are challenges in establishing clear university-industry collaborations in Tanzania. Key issues include the ambiguity of ownership and commercialization of intellectual property created during research, the lack of a defined benefit-sharing mechanism for researchers, and the absence of clear policies regarding intellectual property in universities. While the government has encouraged the formulation of intellectual property policies and conducted awareness programs, no Tanzanian university currently has a formalized IP rights policy in place. The lack of standardized disclosure forms and a clear consensus on IP policies hinder the effective commercialization of research findings, impeding the potential benefits of university-industry partnerships.

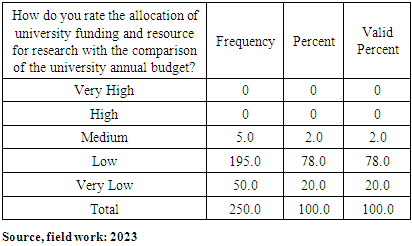

3.2.3. Research Financial Support

|

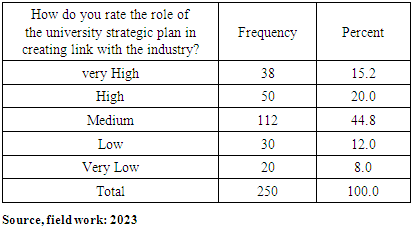

3.2.4. The Role of University Strategic Plans in Establishing Partnerships

|

3.2.5. Academic Staff

- Tanzanian Universities’ Collages, have academic staff from this including PhD holders, MSc holders and the reset are BSc holders virtually higher education instructors specially Phd and MSc holders are from their training and educational attainments are typically responsible for initiating and undertaking research, graduate student supervision, and holding senior management positions.Interestingly, among the study’s respondents, 20% have PhDs, while 62% have MSc holders. After resetting, 18% have BSc holders, so 82% of them have PhDs and MSc holders, can enable universities to implement national and institutional-level strategies and policies to promote university-industry partnership and connect university networks to the national innovation system, but subsequent interview results prove this data.An interview with the associate dean of the University’s Industrial Relations and Technology Transfer by the Faculties of universities: There are limitations to conducting novel research, which is important for attracting academics in academia that are interested in basic research rather than applied research. From the interviews, we can see that the potential of academic personnel for applied research and technology is very low.

3.3. Regression Analysis

- Furthermore, to the descriptive statistical analysis discussed above, in this study, an econometric model (ordered logistic regression analysis) was used to correlate the dependent variable which was status of university-industry collaboration, and the specified explanatory variable including communication, trust, government policy, commitment, funding, culture, experience level, objectives and goals and other factors.The regression results from Table 5 present estimates for various motivating factors that influence University-Industry Partnerships (UIP) in Tanzania. These factors are assessed through an ordered logit model, with each factor’s estimate, standard error, Wald statistic, and confidence intervals provided. Below is an analysis of each variable and its implication on motivating UIP in Tanzania. The table provides the regression coefficient (B) for each variable category, Wald statistics (to test statistical significance) and all important odds ratio (Exp (B)).

|

3.3.1. Communication (COMM)

- The positive estimate of 0.802 suggests that better communication could enhance University-Industry Partnerships (UIP). However, the p-value of 1.000 indicates that this effect is statistically insignificant. While communication is generally important, its actual influence on motivating UIP in Tanzania is unclear based on the available data. Improving communication channels between universities and industries might still be valuable, but further investigation is needed to confirm its impact.

3.3.2. Trust (TRUS)

- The negative estimate of -23.968 suggests that trust might have a hindering effect on UIP, yet the high p-value of 1.000 indicates statistical insignificance. The lack of trust between universities and industries may be a theoretical concern, but the data does not support it as a statistically significant barrier. Nonetheless, building trust should remain a priority to enhance collaboration, but it might not be the most critical factor in the Tanzanian context.

3.3.3. Objective Alignment (OBJ)

- The positive estimate of 2.890 suggests that aligning the objectives of universities and industries can foster UIP, although the effect is statistically insignificant (p-value: 1.000). Objective alignment is essential for successful collaboration, but since this result is not statistically significant, more works needs to be done in practice to ensure that both sectors are aligned in their goals and expectations.

3.3.4. Government Support (GOV)

- The large positive estimate indicates that government support might be a strong motivator for UIP. However, the statistical insignificance (p-value: 0.999) casts doubt on the certainty of this effect. While government involvement is theoretically important, further research is needed to confirm its practical impact. In general, enhanced government policies, funding, and infrastructure aimed at encouraging UIP would be beneficial.

3.3.5. Cultural Barriers (CULT)

- The estimate suggests that cultural barriers may play a role in motivating UIP, with a positive effect, yet the statistical insignificance (p-value: 1.000) indicates no clear relationship. Cultural differences may still play a role in the success of UIP, but the data does not support this with certainty. Addressing cultural barriers through awareness programs, training, and shared experiences could improve collaboration.

3.3.6. Experience (EXP)

- The negative estimate of -6.237 implies that a lack of experience could hinder UIP, but the statistical insignificance indicates that this effect is not conclusive. Although experience can be important, the lack of statistical significance suggests that other factors may have more direct implications for motivating UIP. Developing joint training programs, internships, and research collaborations could help improve experience-based collaboration.

3.3.7. Funding (FUN)

- The negative estimate suggests that funding issues could act as a barrier to UIP. However, the p-value of 1.000 implies this effect is not statistically significant. Funding challenges remain a concern for UIP in Tanzania, but they do not emerge as a decisive barrier according to this model. Continued efforts to improve funding for collaborative research, grants, and industry-focused projects could help stimulate partnerships.

3.3.8. Commitment (COMMIT)

- A positive estimate of 6.269 indicates that commitment between universities and industries is a motivating factor for UIP, but the lack of statistical significance (p-value: 1.000) raises doubts about its robustness. Commitment is a crucial element for fostering successful UIP, but it is not conclusively proven to be a significant motivator based on this model. Strengthening formal.

4. Conclusions

- In summary, the findings of this study highlight key factors that promote and hinder the development of university-industry partnerships (UIPs) in Tanzania. Several key stimuli were identified, including networking opportunities, which 76% of respondents agreed with, with a mean score of 4.4 (SD: 0.68). This highlights the central role that effective networking plays in promoting collaboration between academia and industry. Similarly, research capacity (72% agreed, mean: 4.2, SD: 0.74) and shared goals (70% agreed, mean: 4.1, SD: 0.75) emerged as key elements, indicating that strong research infrastructure and goal alignment between universities and industry are essential for successful partnerships. However, government support (62% agreed, mean: 3.8, SD: 0.82) showed a medium influence, indicating that while government initiatives are important, more targeted policies are needed to further strengthen collaboration. In addition, curriculum relevance (68% agreed, mean: 4.0, SD: 0.77) was highlighted as key to ensuring that university education meets the actual needs of industry.On the other hand, significant barriers limit the potential of UIPs. Limited resources (65% agree, mean: 3.6, SD: 0.8) was identified as the most prominent barrier, indicating that insufficient funding and infrastructure support remain a major challenge. Other barriers, including cultural barriers (58% agree, mean: 3.5, SD: 0.79) and bureaucratic challenges (53% agree, mean: 3.3, SD: 0.85), further complicate collaboration by creating organizational misalignment and slowing down the decision-making process. Mismatched expectations (54% agree, mean: 3.4, SD: 0.81) and lack of awareness (59% agree, mean: 3.7, SD: 0.78) also emerged as significant barriers, highlighting the need for clearer communication and better understanding of the benefits of such partnerships. Addressing these barriers is critical to improving the effectiveness of UIPs in Tanzania.Despite the existence of national policies such as the National Technology Transfer Policy and Intellectual Property Rights Framework, the survey results indicate that the lack of clear mechanisms for industry collaboration, insufficient research funding, and poor policy implementation hamper the overall effectiveness of these partnerships. Notably, 78% of the respondents believed that financial support for research was insufficient, with only 2% believing that funding was adequate. In addition, 45% of the respondents rated the role of the university strategic plan in promoting industrial linkages as moderate, indicating that while a strategic framework exists, its implementation remains weak. The study also found that 82% of academic staff hold advanced degrees, showing the potential to drive research and technology transfer, but their ability to engage in applied research and collaborate with industry is limited due to resource constraints. These findings highlight the urgent need for increased funding, clearer policies, and stronger strategic implementation to strengthen university-industry linkages and promote technological innovation in Tanzania.Ordinal logistic regression analysis provides further insights into the factors that influence UIP. It shows that factors such as communication (COMM), goals and objectives (OBJ), government policies (GOV), culture (CULT), and commitment (COMMIT) have a significant positive impact on UIP development, with coefficients of 0.80, 2.89, 47.69, 22.33, and 6.27, respectively. In contrast, factors such as trust (TRUS), experience level (EXP), and funding (FUN) exhibit negative correlations, with coefficients of -23.97, -6.24, and -0.66, respectively. These results suggest that while factors such as clear objectives, government support, and commitment are critical to the success of UIPs, challenges related to trust, experience, and funding must be addressed. The Wald statistic (all p-values are close to zero) indicates that these findings are statistically significant, confirming that these variables are key determinants of UIP status in Tanzania.Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of university-industry collaborations in Tanzania, highlighting the importance of building strong networks, improving funding and policy frameworks, and addressing cultural and bureaucratic barriers to enhance the potential of these partnerships to drive technological innovation and drive economic growth.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML