-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Information Science

p-ISSN: 2163-1921 e-ISSN: 2163-193X

2017; 7(1): 1-11

doi:10.5923/j.ijis.20170701.01

Investigation of Electronic Information Literacy Level and Challenges among Academic Staffs to Support Teaching Learning in Addis Ababa and Jimma University, Ethiopia 2015; Cross-sectional Survey Method

Mniyichel Belay, Senait Samuel Bramo

Department of Information Science, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Mniyichel Belay, Department of Information Science, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of this study was to investigating electronic information literacy level and challenges among academic staffs to support teaching learning in higher learning institution, Ethiopia, 2015. A cross-sectional study design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection method was used. Two universities were selected purposively and the final sample size of 349 were selected by using simple random sampling from Academic staff/researchers, librarians and university management officials in Jimma University and Addis Ababa University of Ethiopia. Descriptive statistics analysis and qualitative data were worked out. Based on this study, most of the academic staffs in two universities acquire information literacy skills through trial and error, guidance from library staff, assistance from other colleagues and self-taught. The challenges facing on teaching and learning activities, most of responses were strongly agreed for the questions with problems facing in locating the most appropriate information resource, problems accessing too much time necessary to explore the information resources, lack of knowledge of search techniques to retrieve information effectively and problems to retrieve records relevant to information need. 35.9% (115) university/library did not organize information literacy training on use of electronic resources for academic staff member. On the training necessity the majority of the respondent 272 (85.0%) agreed on the universities considering electronic information literacy training for their own staffs.Hence, Librarians and information professionals should be continuous training and retraining of academics on information literacy skills acquisition and adequate provision of electronic information resources in their institution.

Keywords: Electronic Information literacy, Electronic source, Teaching learning

Cite this paper: Mniyichel Belay, Senait Samuel Bramo, Investigation of Electronic Information Literacy Level and Challenges among Academic Staffs to Support Teaching Learning in Addis Ababa and Jimma University, Ethiopia 2015; Cross-sectional Survey Method, International Journal of Information Science, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.5923/j.ijis.20170701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The development of electronics information literacy has been slow in comparison to changes in information communication technologies, and this remains an issue for the higher education sector (Duderstadt & Womack, 2004). Information in the early 21st century is characterized by information overload, unequal distribution, a strong tendency to triviality and increasing concerns about credibility (Sayers, 2006). As the volumes of information are constantly increasing, search skills are required in order to gain access to the information that is available. There is evidence that exposure to technology alone does not adequately develop digital information skills, and more complex factors such as education and attitude must be considered (Brown, C &Nanny, 2003, Chajut, 2010).Given the large investment in educational technological infrastructure over the last 20 years, the failure to engage students in online learning and promote adequate development of Digital Information Literacy is discouraging (OECD, 2004). Case (2007) refers to Julien (2001) in defining information literacy as the ability to make efficient and effective use of information sources. Information literacy includes having the skills to not only access information, but also to ascertain its veracity, reliability, bias, timeliness, and context. The quality of education among academics in any university system depends largely on quality and quantity of information resources at the institution’s disposal. Availability of information resources, accessibility and use are indispensable to the teaching, research and community activities of academic staff members in the university system. The continued existence and relevance of academics in any university system depends on the ability to exploit available information resources either in print or electronic formats. Academics in universities require information to function effectively (Nwalo, 2000; Chukwu, 2005; Oyedun, 2006; and Adetimirin, 2007). While stressing the importance of information for every profession, Haruna and Mabawonku (2001), affirms that legal practitioners depend absolutely on relevant, precise and timely information for success in their profession. Moreover, Julien (2002) believes that an information literate person today should possess specific online searching skills such as the ability to select appropriate search terminology, logical search strategy and appropriate information evaluation. However, one barrier to the efficient utilization of information resources especially digital resources in developing countries is the relatively low level of information literacy skill (Julien, 2002; Tilvawala, Myers and Andrade, 2009). As users of information community, academic staff members are faced with diverse, abundant information choices in their pursuit of knowledge because of the complexity of information sources and formats. This poses new challenges for academic staff members in evaluating and understanding the content. The uncertain quality and expanding quantity of information pose big challenges for any society. It is evident from literature that access to information resources can immensely improve academics’ teaching and research productivity. However, the nagging challenges such low information literacy skills among academics in developing countries as reported in literature can be noted; thus, the need to examine the influence of information literacy skills on research productivity /or teaching and learning process of academic staff in Ethiopia higher institution.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

- E-information literacy has become a crucial skill in the current knowledge and information society particularly in university communities. However, a number of challenges impact on the access of users to electronic information, including those that go beyond just the technologies available to users and the skills they have for using them (Pedro, 2007). Without the ability to manipulate and use information effectively by academics, the significant investment by university libraries, and other national and international donor agencies to ensure access to and use of information resources for the use of teaching, learning and research may remain grossly under-utilized and a waste of investments by academics in Addis Ababa and Jimma universities. In using the electronic resources, academic staffs of both universities faced problem with locating and evaluating information, which impedes its effective use. The study was investigated the gap of information literacy skills and how it affects the effective use of electronic resources among staff of the University of Addis Ababa and Jimma.

1.2. Research Questions

- Ÿ What methods do academic staff members use to acquire electronic information literacy skills?Ÿ What are the electronic information literacy skills possessed by academic staff members in Ethiopia higher learning institution?Ÿ What is the level of the electronic information literacy skill among academic staff in Ethiopia higher learning institution?Ÿ What is the relative contribution of electronic information literacy skills to the determination of productivity of academics in Ethiopia higher learning institution?

1.3. Objectives of the Study

- The main objective of this study is to investigate electronic Information literacy level and challenges among academic staffs to support teaching learning in higher learning institution, Ethiopia, 2015. The specific objectives were: Ÿ To determine electronic information literacy skills possessed by academics staff in Ethiopia higher learning institution. Ÿ To examine the level of electronic information literacy skill among academic staff in Ethiopia higher learning institution.Ÿ To investigate the influence of the ability to locate and access information on productivity of academic staff in Ethiopia higher learning institution.Ÿ To find out the contribution of electronic information literacy skills to teaching and learning process in Ethiopia higher learning institution.

1.4. Significance of the Study

- With the development in electronic information resources, academics in general have recognized the capabilities of ICTs. The study provide information that assist library managers in the design, development and formulation of institutional research policies in the changing global situation; and in particular, highlight those factors that should be emphasized in order to further encourage academic staff increase their research productivity. The findings enhance the academic staff development and capacity building drive in the area of information use and ICT in Ethiopia Higher learning institution. Finally, it added to the body of knowledge of literature in library profession on information literacy, use of information resources and productivity among academic staff in Ethiopia Higher learning institution.

1.5. Scope and Limitation of the Study

- The study mainly focuses on electronic information literacy level and challenges like skills of Academic staff in identifying, locating, searching, accessing, retrieving and using information from electronic sources of information. The sample of this study covers all Academic staff/researchers, librarians and university management officials in Addis Ababa and Jimma University.

2. Literature

2.1. Overview of Information Literacy

- Information technology, as defined by Oketunji (2002), is the application of computer and communication technology to information handling. The use of these technologies requires training, which brings about information literacy. Information literacy includes library literacy, media literacy, computer literacy, research literacy, and critical thinking skills. Information literacy, as viewed by Bruce and Candy (2006), is a global issue, with particularly strong efforts and examples in North America, Australia, South Africa, and Northern Europe. Academic staffs are working to integrate information skills instruction into the curriculum to achieve relevant learning outcomes. The era of mass higher education has led to the challenge of increasingly divergent student study skills. The need to use a mix of print and electronic resources, and the explosion of materials freely available on the web, has made the search for information seem easier to do and more complex to manage (Godwin, 2006). Bruce (1999) emphasizes the importance of critical thinking, an awareness of personal and professional ethics, information evaluation, organizing information, interacting with information professionals, and making effective use of problem solving, decision making, and research skills. Resource-based education encourages better use of information resources and services (Bruce, 1999).Information literacy is a cumulative process, which must be adapted to the requirements of each learner. Barriers to the development of information skills are identified by Godwin (2006) and include lack of appreciation and ignorance shown by teaching staff: The perception that all that is needed is to use a library catalogue and the library databases comes from their inability to find time to grapple with the effects of information explosion, Lack of institutional commitment to information skills combined with absence of time slots in the curriculum. The final barrier belief that they already know how to get information and are apathetic about receiving any professional help (Godwin, 2006), A number of studies of Internet use have been done by African authors. Jagboro (2003) as quoted by Omotayo (2006) reports that majority of academic staff of Obafemi Awolowo University ranked fourth on the use of Internet. A study by Omotayo (2006) observes that undergraduates learn the use of Internet through their friends. Badu and Makwei (2005) looked at awareness and use of the Internet in Ghana.

2.2. Use of Information Resources for Teaching and Learning of Academics

- The provision and efficient use of information resources in university libraries are central to any meaningful research, teaching, and community service delivery by academics in the universities. The use of information resources in whatever format by academics in universities has been studied by Ehikhamenor 2003; Aduwa-Ogiegbaen and Stella 2005; Adogbeji and Toyo 2006; Ureigho, Oroke and Ekruyota 2006; Osunade, Phillips and Ojo 2007; and Popoola 2008. Shokeen and Kaushik (2002) noted that social scientists of universities in India most frequently use current journals, textbooks and reference books. Agba, Kigongo-Bukenya, and Nyumba (2004) reason that the shift from print to electronic information implies that both academic staff and students in a university system must use these resources for better quality, efficient and effective research more than ever. Abels, Liebscher and Denham (1996) say networked services can benefit smaller institutions in particular, because academics and students have access to peers worldwide. They also have access to news and discussion groups, library catalogues of large research libraries, datasets (aggregated services) and databases and even public domain software packages for teaching and research. Popoola (2000) argues that social scientists in the higher institution utilize the library information services such as current awareness, photocopying, referencing, statistical data analysis, E-mail, selective dissemination of information and on-line database searching, in support of their research activities. The study reveals that majority of academics use printed sources more than e-sources, but they also use e-sources quite frequently. However, it is discovered that what they use mostly are books, websites and printed journals. It has also been found that there is greater use of e-sources among younger members of the academic staff members. Also, the results indicate that the use of e-sources is positively influenced by the respondents’ perceived usefulness of resources to their research productivity and as well as the convenience of access to the sources. Okiy (2000) submits that students and academics in Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria make use of book materials such as journals, newspapers, textbooks magazines, dictionaries, projects, encyclopedias and government publications. In the same vein, Kenoni (2002) carries out a study on the utilization of archival information by researchers in the University of Nairobi, Kenya and reports that academics make use of maps and atlases, gazettes, theses and dissertations, newspapers, statistical abstracts, video films, political records, journals and conference papers, books for their research activity. Madhusudhan (2007) conducts a study on the internet use by research scholars in University of Delhi and the results indicated that researchers, like others elsewhere, are beset with the problems of inadequate computers with internet facilities, slow internet connection, and lack of skills and training. The survey also reveals that 57 per cent of the respondents are facing retrieval problems. It also reports that some scholars lack research techniques and training. Agbonlahor (2006) examined factors which motivate academics in Nigerian universities to use information technology (IT). The study reports that perceived usefulness (relative advantage) and perceived ease of use (complexity) significantly influence the use of IT by lecturers in Nigerian universities. Furthermore, both training (information literacy skills) and level of access to IT significantly influence the number of computer applications used by lecturers in their research activities.

2.3. Staff’s Beliefs and Behavior Regarding Information Literacy

- To better understand the perspectives of discipline-based academics, Bruce, etal. (2006) aptly warned that there are different ways in which teaching, learning and information literacy may be approached. Whether a student, academic or librarian, it is not uncommon for such individuals to adopt different views in different contexts about learning and teaching.Generally academic communities value the services offered by librarians although a deep appreciation by all for the full involvement that librarians make to the educative mission of universities is not always apparent. Several dated research claimed that the attitudes of academics towards librarians are negative and subordinative in nature (Cook, 1981; Divay, et al. 1987; Haynes, 1996; Oberg, et al. 1989). Academics’ perception of information literacy has been given limited attention in the research literature. McGuiness (2003) discovered that academics do not necessarily value the contribution of librarians to teaching and learning. She further noted that much of the literature about information literacy education was written by librarians for librarians as it was assumed that librarians play the key educational role. Apart from McGuiness’ study of Irish academics, Bruce (1999) conducted a phenomenographic study of Australian university educators. In Canada, Leckie and Fullerton (1999) surveyed science and engineering faculty. In America, Wu and Kendall (2006) studied San Jose State University while Brooks, et al. (2007) focused on the University of Michigan - Dearborn. Similarly Boon, et al. (2007) investigated United Kingdom English academics conceptions of information literacy. In the most recent research, the findings of Wu & Kendall’s (2006) research into teaching faculty’s perspectives on business information literacy revealed that all faculty staff who were surveyed expected their students to use library research for their assignments. It was also determined that the teaching of aspects of information literacy by librarians was essentially an expectation by teaching faculty. With a very high response rate, the results were positive in terms of collaborating with librarians, referring students to them for assistance in term projects and requesting library instruction/lecture.

2.4. Information Literacy in Higher Education

- Rapid technological changes, proliferating information resources via different sources and medium, together with the uncertainty in the quality of information pose large challenges to society and add to the information literacy dilemma. In particular, Hepworth (2010) recognized that evolving technologies such as virtual learning environments and freely accessible learning and information retrieval tools impact on the learning and teaching environment since they are usually easy to use and are more user friendly with a functionality that directly addresses learners’ needs. Developing lifelong learners as a graduate attribute is central to the mission of most higher education institutions. Harrison and Newton (2010) concluded from their research that a strong relationship existed between performance on the information literacy skills assessment and students’ academic performance throughout their degree program.Bruce, et al. (2002) advised that information literacy as focal to the academic experience within the university community should be explored and developed. Supporting such a suggestion, relevant literature pinpoints the need of a pedagogic framework for delivering effective information literacy programs (Arnold, 1998; Carder, et al. 2001; Cooney & Hiris, 2003; Dennis, 2001; Doherty, et al. 1999; Korobili, et al. 2008; MacDonald, et al. 2000). Further support is offered by Bruce and Candy (2000), Limberg (2000) and Lupton (2004) who believed that information literacy is strongly associated with learning. As Parker (2003) noted, information literacy is becoming an increasingly strategic issue for universities where the onus is placed on learning and teaching strategies that deliver the skills that students need to thrive in an increasingly competitive graduate employment market. Possessing information literacy skills extends learning beyond classroom settings as individuals take such learned skills with them as they graduate from university and take responsibilities in other facets of their life. Electronic literacy skills for staff might include knowledge of the range of resources available in the digital library, such as which journal titles are available in electronic format. But it would also include teaching a member of staff to build an online reading list and add stable links to electronic journal articles. E-literacy also involves knowledge about copyright and licensing arrangements for electronic resources, what Martin (2003) terms, moral issues.

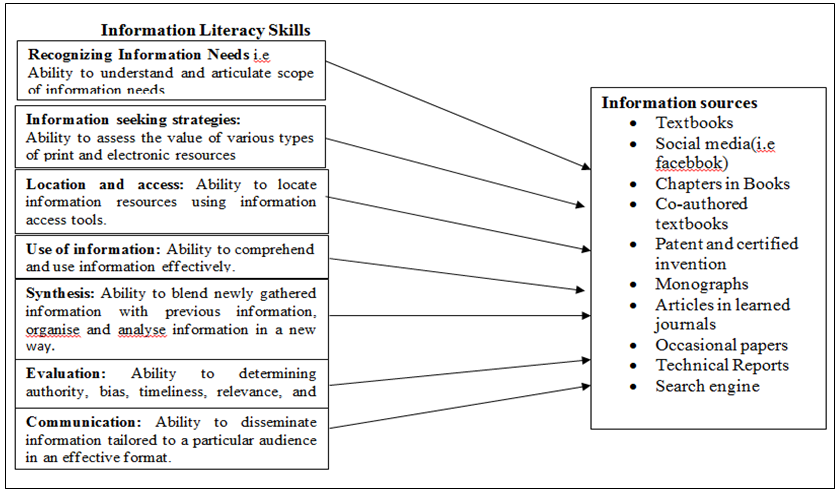

2.5. Conceptual Framework

- Academics engage in teaching and learning and research productions will always seek information to accomplish these productivity tasks. These information resources could be found in different places such as libraries, computer laboratory, databases and internet within the university libraries, departments, colleges and outside. The use of any of these information resources by academics for teaching and learning and research purpose is determined by some factors may affect academic staff members’ productivity, such as: skill to recognize a need for information; to distinguish ways in which the information “gap” may be addressed; to construct strategies for locating information; to locate and access information; to compare and evaluate information obtained from different sources; to organize, apply and communicate information to others in ways appropriate to the situation; and finally the skill to synthesize and build upon existing information, thus contributing to the creation of new knowledge. It is also assumed that an academic staff will always want to use information resources to satisfy his/ her activities need.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Method

- The research method used for the study was cross sectional survey method in Addis Ababa and Jimma university of Ethiopian. The researchers were chosen to use both qualitative and quantitative research design. Qualitative dimension refers to data that was collected from some top management through interview whereas; quantitative data was collected from academic staff and librarian using questionnaire.

3.2. Population, Sample Size and Sampling Techniques

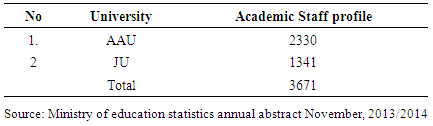

- There are 33 universities established in different parts of Ethiopia. Out of 33 universities 12 were established recently and are in the process of developing electronics resources management and approach to electronic information literacy. Twenty one of them are more experienced on developing digital resources and relatively advanced on the use. Therefore, in this study two universities were selected purposively based on their level of effort on electronic information literacy and their proximity to study sponsoring institutions namely, Jimma and Addis Ababa University with total population size of 3671(Ministry of education statistics annual abstract, 2013/2014).The researchers would be used simple random sampling technique to select a sample size of 349 respondents from different professionals or experts who have knowledge about electronic information literacy (academic staffs). Key informants of librarians and university management officials were also interviewed because they considered good background on the area and some questions may not be fully answered by the questionnaire or extra questions can also raise for the interviewee which was not asked by respondents by the questionnaire.The total populations identified for this study form selected universities were 3671. From this total number of populations 2330 were from Addis Ababa University and 1341 academic staffs were from Jimma University. The sample size was determined using single population proportion formula. Based on the formula, from 3671 academic staff, 349 (three hundred forty nine) of them were taken. Sample size allocation (proportional allocation for academic staff) for Addis Ababa University was 221 and Jimma University 128. The final study population was used by computer generated method.

3.3. Data Collection

- The instruments for this study were the self-administered questionnaire and interviews as well as observation were used.

| Figure 1. Conceptual framework for information literacy skills and academics performance (Self constructed) |

3.3.1. Questionnaires

- The questions and statements of the questionnaire would be grouped and arranged according to the particular objective that they can address.A four section instrument would be used to collect data from staff ’ in selected University (Jimma and Addis Ababa University) containing the following sections: (a) Socio demographical information (profile) of respondents (b) electronic information literacy trends of selected University and (c) technological support in facilitating electronic information literacy (e) challenges of electronic information literacy.

3.3.2. Interview

- Interview was conducted with library staff and management officials among Jimma University and Addis Ababa University. The researcher would be interviewed 5 respondents to gain in-depth data about levels and challenges of electronic information literacy in higher intuition that implies on teaching and learning process.

3.3.3. Data Quality Control

- The questionnaire was pre-tested on 5% of the total sample size (349) out of study area. Data was collected by one trained supervisors and four trained data collectors recruited from experienced people and brief orientation would be given to the data collectors and site supervisors. At the end of each day, the questionnaire was checked for completeness and consistency by the supervisors.

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

- Letters for permission to a structured questionnaires and interview by the researchers were written by Academic Research of Jimma University College of natural science to both Jimma and Addis Ababa universities. After receive permission from each university, the data collectors select the study population from the total population based on computer generated method and adjusts his/her time to give the awareness and an instruction for volunteer staff that was selected as sample.

3.5. Data Analysis Procedure

- The quantitative data was gathered are analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Important and significant comments from the open-ended questions and qualitative data were noted down and included to support and elaborate appropriate findings.

|

4. Data Presentation, Analysis, Results and Discussions

4.1. Response Rate

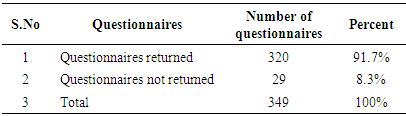

- Among the 349 distributed questioners, 320 were returned and 29 were not returned. Among 29 non returned questionnaires 10 questionnaires was not returned from Jimma University and 19 questionnaires was not returned from Addis Ababa University. Summary of the response rate is presented in table 2 below:

|

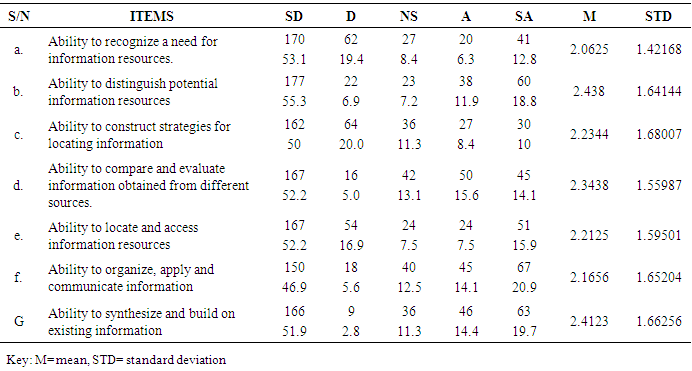

4.2. Electronic Information Literacy Skills/ Level

- As indicated in table 3 the response to information literacy skills shows that respondents with ability to distinguish potential information resources skill had the highest number of mean score of 2.438. This is closely followed by respondents with Ability to synthesize and build on existing information (2.4123), while respondents with Ability to compare and evaluate information obtained from different sources have mean score of 2.3438. However, respondents with Ability to construct strategies for locating information mean of 2.2344. The finding, however, shows that the mean scores of each of the seven components tested under the information literacy skills is lower than the mid-point scores of 2.5 on a scale of five. Therefore academics in Addis Ababa and Jimma universities do not possessed electronic information literacy skills based on the overall mean scores.

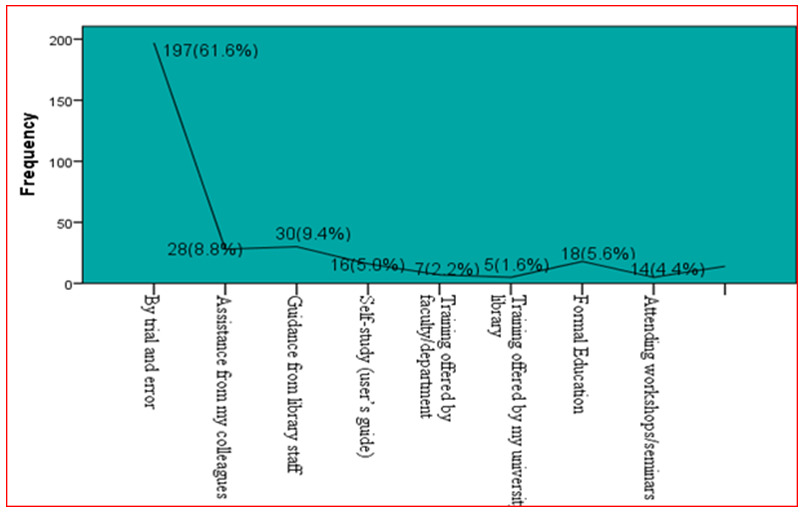

4.3. way of Acquiring Information Literacy Skills in the Universities

- The result in figure 2 shows that majority of the academic staffs in Addis Ababa and Jimma universities acquired information literacy skills through trial and error (61.6%). This view assertion that, information literacy skills acquisition has not been accorded its position in the institutions, in line with Kumar and Kumar (2008) in the colleges of Bangalore City on the perception and use of e-resources and the Internet by the engineering, medical and management argued that many of the students and faculty learn about the electronic information sources use either by trial and error or through the advice of friends. In the same vein, Mookoh and Meadows (1998) in South Korean universities reported that academic staff members were having difficulty in using information technology due to lack of suitable training staff. However, the finding is differ with the study of Baniontye and Vaskevicene (2006), which reported that 90% of research libraries and 65% of public libraries in Lithuania provide regular formal training for their users. Most of the respondents (96%) agreed that they possessed the skill to recognize a need for information and that their ability to use of information resources has greatly influenced their research output.

|

| Figure 2. Method of acquiring of information literacy skills in the universities |

4.4. Challenges Facing when Embarking on Teaching and Learning Activities

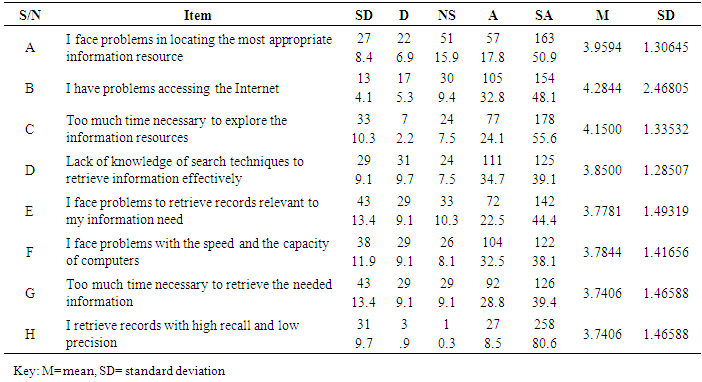

- To reveal the respondent’s observation of electronic information literacy challenges in their respective universities. The result presented in table 4 shows that respondent also strong agree with the statements of facing problems to retrieve records relevant to my information need with the mean value, and also respondents strongly agree with the statement of face problems with the speed and the capacity of computers. This indicated that respondents were strongly agreed with the challenges of electronic information literacy among academic staff.

|

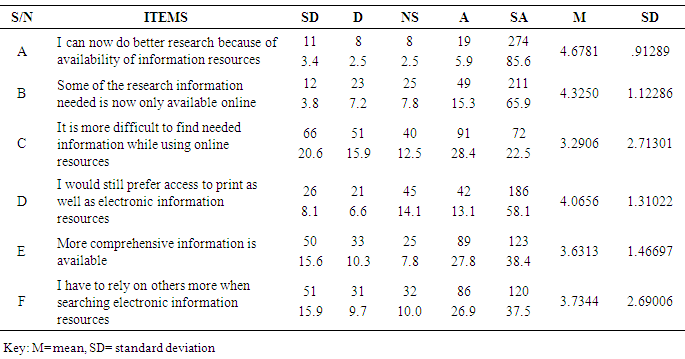

4.5. Importance of Information Resources to Your Teaching and Learning Activities

- To find out the respondent’s opinions about the usefulness of information resources to different activities, the result presented in table 5 shows that the most response were strongly agreed with doing better research because of availability of information resources in electronic information literacy with the mean value (4.6781), Some of the research information needed is now only available online with mean value (4.3250), It is more difficult to find needed information while using online resources with mean value (3.2906), still prefer access to print as well as electronic information resources with mean value, More comprehensive information is available with mean value (3.6313) and it rely on others more when searching electronic information resources with mean value (3.7344).

|

4.6. Consider the Training Necessarily on Information Literacy

- Majority of the respondents 35.9% (115) say university/library did not organize information literacy training on use of information resources for academic staff member. On the case of the training necessity the majority of the respondent 272 (85.0%) agree the universities considering electronic information literacy training for their own staffs.

4.7. Open-ended Responses Analysis (Qualitative Analysis)

4.7.1. Levels of Respondents on Electronic Information Literacy

- Academic staff possesses low understanding of the concept of electronic information literacy, some of the respondents’ “states that people require some level of information skill to make decisions and cope with quality of teaching and learning in the university”. This means that effective use of information is indispensable for effective performance in life, including academic process. Further support for this finding Written on the relationship between information literacy skill and academic productivity by Found (2000) asserted that access to sophisticate information tools without a conceptual base for use result in the diffusion of meaningless research efforts. According to him, critical inaccessibility on the other hand deals with the users’ inability to analyze and evaluate the content of the material in term of its currency. Explaining the above findings of the study further, Wilson (2001) argued that the tremendous increase in the need for information literacy for academic productivity was not unconnected with the exponent growth of information, resulting from digital information. According to him, the need to find, evaluate and effectively use of information has always been with us, however, with increased understanding of the learning process and internet access to unedited works, the academics in universities are faced with diverse and abundant information choices in their academic works.

4.8. Interview and Observation

- In this study, On how universities practice or experience in creating, generation, organization, utilization and dissemination of electronic resources that might be of value to their academic and research endeavor, most of the interviewees reported that “their respective institutions did not organize, manage and disseminate, and they are not prepare proper training to develop skills of electronic information literacy”. However, one of Addis Ababa University respondents mentioned that “over the last few years their university has been involved in initiatives and projects that aim to provide better access to electronic resources for teaching and learning process”. Therefore, Library staff of Addis Ababa and Jimma University has observed that by developing online courses the information literacy of academic staff has improved. Staffs are encouraged to use existing library resources available through subscription databases. Part of the training they are offered shows staff how to identify library resources. Therefore they often discover new resources and learn more about the library. Librarians are supposed to coordinate the evaluation and selection of intellectual resources for programmes and services offered by universities; organize, and maintain collections and points of access to information; and provide advice and coaching to students and academic staff who seek information (CAUL, 2001:3) in collaboration with the faculty. Respondents from librarians in respective universities reported that “they did not have formal Information Literacy programmes except for a few informal aspects of it such as library orientation, instruction in computer skills and Internet access, and others as were given at the beginning of the first year through a short lecture during the induction week. And they had drawn up an Information Literacy programme but were awaiting approval by the University Council before it is integrated into the university curriculum”.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Academics’ research productivity in universities was reported high in journal publications, technical reports, conference papers, working papers and occasional papers while on the downside in textbook publications, chapters in books, monographs, patents and certified inventions. However, we conclude that there were from the findings of this study, lack of skills possessing of electronic information literacy which includes ability to recognize a need for information resources, distinguish potential information resources, construct strategies for locating information, compare and evaluate information obtained from different sources, locate and access information resources, organize, apply and communicate information, and ability to synthesize and build on existing information and these had greatly influenced their research productivity and teaching learning activities. While the challenges facing on teaching and learning activities viewed by instruments that were problems in locating the most appropriate information resource, problems accessing the Internet, too much time necessary to explore the information resources, lack of knowledge of search techniques to retrieve information effectively, problems to retrieve records relevant to my information need, problems with the speed and the capacity of computers, too much time necessary to retrieve the needed information and retrieve records with high recall and low precision. Therefore, to solve those problems, there should be organized continuous training and retraining, of academics on information literacy skills acquisition of the staff in the libraries on the use of information resources, linking electronic information sources to library websites for users to access and; Preparing and using for teaching materials and organizing workshops and seminars specifically designed for creating awareness and deeper understanding of electronic information literacy so as to efficiently assist academics in accessing and retrieving information for research productivity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank all of the participants of Addis Ababa and Jimma University and thank to Jimma University college of Natural Science for funding this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML