-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Inspiration & Resilience Economy

2020; 4(1): 25-34

doi:10.5923/j.ijire.20200401.04

The Reconstruction of Family Identity through Food Consumption- The Case of Displaced Syrian Women in Jordan

Noor Jayousi

Lecturer in Marketing, University of Bahrain

Correspondence to: Noor Jayousi , Lecturer in Marketing, University of Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The objective of this research is to address the role of food consumption on the reconstruction of family identity using the case of displaced Syrian women in Jordan after the Syrian conflict in 2011. This paper used qualitative research method. Nine in-depth individual interviews were employed to collect data. Besides, a focus group was conducted to validate the data collection process. A conceptual framework that explains the relationship between food consumption and family identity was devised using interpretive phenomenological analysis. The findings of this study show that the reconstruction of family identity is underpinned by communal food preparation, valuing traditional food and economic decision-making. Moreover, the study reveals that the coping strategies adopted by Syrian women refugees include religious celebrations, food storage and social networks. The study recommends to expand research to include different target groups in other regions. The originality of this research stems from the fact that this study sheds light on the linkages between food consumption and family identity among Syrian women refugees in Jordan using interpretive phenomenological research.

Keywords: Consumer behavior, Family identity, Food consumption, Syrian crisis, Women refugees, Displacement

Cite this paper: Noor Jayousi , The Reconstruction of Family Identity through Food Consumption- The Case of Displaced Syrian Women in Jordan, International Journal of Inspiration & Resilience Economy, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2020, pp. 25-34. doi: 10.5923/j.ijire.20200401.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Displacement can be attributed to many reasons, such as natural disasters, human atrocities or armed conflicts. Articulating the linkages between the roles of consumption in maintaining family identity during displacement is critical to comprehending the interaction between consumption patterns of displaced people and its role in shaping family identity. Displacement in this study is going to be addressed in the context of women Syrian refugees in Jordan who have been forced or obliged to flee or leave their home or place of habitual residence. A literature review included studies related to crisis and transition in relation to consumption, such as unplanned transition events including divorce (Bates & Gentry, 1994). Less research has been done on the role of consumption in maintaining family identity during displacement for women Syrian refugees. Previous literature has addressed the role of meal preparation, display and consumption in maintaining family identity (Epp and Price, 2008). Also, family meal consumption practices, such as grocery shopping, meal preparation (Moisio et al., 2004) and meal sharing (Cappellini and Parsons, 2012), play an important role in managing the division of household labour (Kemmer, 1999). Food acquisition and preparation creates a sense of bonding, love and caring between family members (Cappellini and Parsons, 2012). Food therefore allows consumers to reconstruct, shape and maintain family identity. The Syrian crisis, which started in 2011, is a serious humanitarian conflict which resulted in an influx of around 4 million refugees to the neighboring countries including: Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon and Turkey. This conflict is considered one of the greatest displacements since World War II (Andres-Vinas, et al. 2015). The conflict resulted in displacing over 1 million Syrians to Jordan in refugee camps and in northern governorates, which reflected on the public utilities, schooling, health services infrastructure, and employability in Jordan (Bilukha et al., 2014). The paper intends to explore the relationship between family identity and food consumption patterns. More specifically, the research questions in detail are outlined below:1) What is the role of food consumption in shaping family identity for women refugees? 2) What are the strategies applied by displaced Syrian refugees in order to cope with changes in food consumption? This paper will begin with a theoretical framework on family identity and displacement. The methods used for data collection will be outlined next, followed by a number of emergent themes as part of the findings. Finally, conclusions and recommendations will be outlined for future research.

2. Literature Review

- The literature review will cover two components, i.e. family identity and displacement, as outlined below. Family IdentityThe literature defines identity as a process of co-creation between individuals and community in a socio-political context (Erikson, 1959). Also, identity can be explained as a journey of an individual’s constructed history that is shaped by place (Holt, 2007). According to Kuus (2007) identity is not a one-dimensional concept but a complex and a contested term that includes a wide diversity of attributes including age, nationality and religion (Holt, 2007). As defined by (Fiese and Wamboldt, 2000) family identity is the family’s subjective sense of its own continuity over time, its present situation, and its character. It is the gestalt of qualities and attributes that make it a particular family and that differentiate it from other families. The concept of family identity is conveyed as a group of psychological phenomena, which have as their essence a shared system of beliefs. To elaborate, shared belief systems are implicit assumptions about the roles, relationships and ethics that govern interactions within families and other groups (Fiese and Wamboldt, 2000). Family identity is influenced by a number of elements, i.e., structure, character and generational components. Family structure reflects the roles of family members, boundaries and patterns of family membership (Epp and Price, 2008). Family character captures the regular activities that families engage in as part of shared characteristics or personalities within the family, such as common values or tastes (Bolea, 2000). Moreover, family identity can be divided into individual identity and group identity (Scabini and Manzi, 2011). Individual identity is defined as the subjective concept of oneself as a person (Scabini and Manzi, 2011). Group identity where people start to perceive themselves less as individuals and more as part of a community (Agnew et al., 2008). The levels of family identity may be challenged during transitional periods (Scabini and Manzi, 2011). Consumer research has found that family identity is a determining factor during transitions when identity is questioned, re-examined or reviewed (Epp and price, 2008). Transformative events include social, economic, and political imbalances that induce immediate changes to family identity (Epp and Price, 2008). Transitional periods cause shifts in boundaries and changes in roles (Gentry et al., 1995). Moreover, many family transitions that become crises include a combination of cumulative stress and evolution. The term family crisis denotes disruption in the family’s social system (Lavee et al., 1987). A crisis occurs when the family can no longer access and manage its resources due to loss of control and sense of insecurity (Hill, 1958). Major crisis including war and armed conflicts are unpredictable and cause severe family disruptions. However, families tend to respond and adapt to such crisis through seeking support from one another to survive and overcome the hardships (Bennett et al., 1988).The role of consumption during transition can be conceptualized in the form of rituals. As a symbolic form of communication centred in the home. Rituals have the power to organize the family due to their patterned nature (Pleck, 2000). Comprehension of how family identity is created has substantial implications for understanding consumption (Epp and Price, 2008). Consumption is viewed as a coping mechanism, which can be used to restore or build a sense of family identity during family disturbance or stress (Burroughs and Rindfleisch, 1997). People respond to crises by adopting a number of coping strategies. These coping strategies include: changes in consumption patterns (Rindfleisch et al., 1997). Another form of coping is withdrawal from society due to inability to adapt or accept reality (Stephens et al., 2005). In contrast, past literature showed that Immigrants might demonstrate defence strategies like abstaining from consuming certain products as a form of resistance (Penaloza and Price, 1993). In sum, transformative events linked to consumption-related behaviours were addressed in previous literature. However, less research has been done on the role of consumption during displacement. This research intends to address this knowledge gap by investigating the role of consumption in shaping, defining and reconstructing family identity. Displacement Relocation of people entails hardships, suffering, and trauma. Displacement due to unanticipated events such as war creates a sense of vulnerability and helplessness (Newman and Van Selm, 2003). Relocation is related to loss of social context that causes instability and risk to identity (Ferris et al., 2013). People who move in such risky conditions in search of a secure place are referred to as refugees (Phuong, 2005). Refugee is a legal term applied that defines individuals who were forced to abandon and move from across border in search of security.The identity of a refugee evolves in time and place (Holt, 2007). This influence is partially due to the existing legal infrastructure in the destination country; different places respond to resettling refugees in different ways (Holt, 2007). Refugees experience a process of identity reformulation and strive to assimilate and adapt to new social, economic, cultural and political context. In essence, the label of a refugee entails a non-steady, dynamic and transient process of search for identity and home (Akcapar, 2006). Refugees are obliged to face new realities and new labeling that indicate a sense of being a stranger. This feeling of being an outsider influences the process of reconstructing family identity in the new home. The label of refugee impacts his destiny and his search for new identity (O'Neill and Spybey, 2003). The societal image is particularly important in the reformation of the refugee’s new identity. The refugee label embodies a social stigma that is shaped by (O'Neill and Spybey, 2003). political discourse and media. The challenge is that refugees are perceived as economic burden and competitors with local people for jobs and services (Zetter, 2007). Moreover, the refugee is referred to as “the other, which adds complexity to the process of the reconstruction of identity.

3. Methodology

- Qualitative research was conducted to gather data using in-depth interviews and a focus group. Qualitative research revolves around obtaining profound insights into human behaviour and the drivers behind such behaviour. Consequently, qualitative research serves the purpose of this research in the context of generating insightful comprehension in the examination of family identity, consumption patterns and displacement. Nine in-depth individual interviews were employed as a method of data collection, to obtain profound details about beliefs, attitudes, values and opinions. In addition, a focus-group discussion was conducted for women refuges to gain more insights. An opening question was followed by a set of follow-up questions to explore more detailed answers underlying connections and motivations. The interviews were held in Amman city, during July 2017. Each interview lasted for approximately two hours and the informants had the chance to answer, clarify and explain their opinions and thoughts in a free environment. Interviews were conducted in Arabic depending on the informants’ language proficiency, and were afterwards translated and transcribed in English. The key areas of questions were primarily related to food consumption practices, celebrations, traditions, and coping strategies. Purposive sampling was applied in this study. A sample of Syrian women refugees in Jordan was selected according to a particular judgment made by the researcher to estimate the suitability of respondents. The informant characteristics that met the requirements of the study were: (1) age group ranging from 25–35 years of age, (2) residents in the urban area of Amman city in Jordan, and (3) female gender. Syrian women refugees were selected through a resource person who works in a relief agency for Syrians. The reason for choosing participants of the study to be women is the fact that literature highlight women as key pillars for managing and maintaining family stability (Cappellini and Parsons, 2013), and their significant role in transmitting traditions across generations (Pleck, 2000). In addition, women contribute to household informal and indirect income (Rizavi and Sofer, 2008). This research adopted the phenomenological research so as to fulfil a knowledge gap in understanding a social phenomenon, which entails multiple interactions of events (Ehrich, 2005).Existential phenomenology seeks to describe experience as it emerges in some context (Flood, 2010). Hence, understanding existential phenomenology is accomplished through describing lived experiences and the meanings that develop from them. Also, interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) was used to provide rich interpretation of idiographic subjective experiences (Biggerstaff and Thompson, 2008). Since this study aims to generate insightful comprehension on the role of food consumption in maintaining family identity, IPA analysis was utilized for data analysis. The process for the interpretative phenomenological analysis as proposed by Biggerstaff and Thompson’s (2008) study is a cyclic process that can be summarized in the following steps: conducting semi-structured interviews that covers a number of themes in order to gather data from participants. Later, each interview recorded is transcribed in explicit detail in order to get accurate insights. Next, transcripts are analyzed through linking data with the original recordings. During transcript analysis, the researcher starts making notes any of ideas and reflections that appear during reading the transcript (Biggerstaff and Thompson, 2008). Prejudgments and assumptions are set-aside during the note writing (Husserl, 1999). The final stage is to develop a table of themes. These emerging themes are best located in an ordered manner which reflects the main issues identified in accordance to the research objectives. As will be shown later.

4. Analysis and Findings

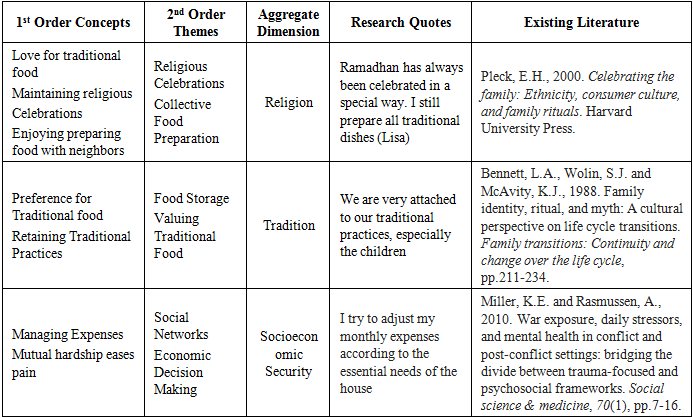

- Based on the above methodology, the following table was constructed. Table 1 outlines a number of elements which includes 1st order concepts were extracted from the informant’s statements. 2nd order concepts themes and domains were condensed from the original key phrases. The third order linkages between themes and models were conducted.

|

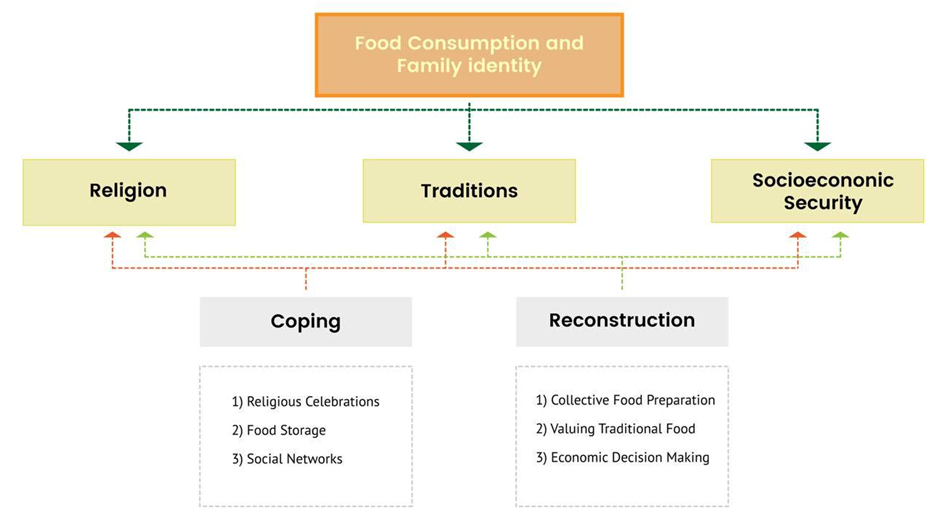

| Figure 1. A Conceptual Framework for Family Identity and Food Consumption |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- The following summarizes the two research questions in light of the inductive qualitative analysis. A discussion on how Syrian women cope with changes and reconstruct family identity through food consumption will be outlined below: Research Question 1: What are the strategies applied by Syrian refugees in order to cope with changes in food consumption? The research demonstrates a number of coping strategies as a mean to strengthen family identity during displacement as shown in Figure 1. The manifestation of these constructs has significant characteristics in food consumption practices among Syrian refugees, establishing unique cultural and socioeconomic influences. These coping strategies include: religious celebrations, food storage and social networks. Religious Celebrations as a coping strategy: Recent Literature shows that family rituals are a symbolic form of communication centered in the home and have the ability to organize the family due to their patterned nature. Celebrations are a form of family rituals that can be divided into weddings, funerals and religious celebrations (Bennett et al., 1988). Traditional celebrations present occasions celebrated in a cultural context and reassure people about the continuity of their family identity during life changes (Pleck, 2000). Family rituals can play a distinct role in maintaining and resolving family relationships during times of stress and transition (Bossard and Boll, 1950). As a result, celebrations help to strengthen group solidarity and rectify conflict as a means of social control (Schachner, 2001). The findings of this study show the importance of traditional food during religious celebrations for Syrian women refugees. While celebrations are seen as links to the past (Pleck, 2000), the revival of religious rituals such as fasting and praying along with traditional meals facilitated the coping process for the displaced informants. Moreover, it was found that traditional sweets (e.g. pastries) in religious celebrations like Eid constitute a key component of social celebration and hospitality. Consequently, renewing the entertainment and past memories of celebrations. Food Storage as a coping strategy:Traditions occur with regularity in most families and generate a feeling of intimacy for surviving the difficult times (Whiteside, 1989). Traditions come in the form of anniversaries, birthdays, family visits and special meals (Bennett, 1988). Food meal choices embody the historical memory for shared experiences (Almerico, 2014) and reflect the norms, values and social preferences (Stajcic, 2013). As a result, traditions are actively connected to the creation and reproduction of family identity (Wolin and Bennett, 1984). The findings of the study highlight the role of women in transmitting traditions (Pleck, 2000), and sheds light and the commitment of Syrian women to maintain traditional practices such as storing food. This practice was found to create a sense of security and continuity to the informants. The majority of informants were found to store basic food such as (e.g. sugar, rice and olive oil) despite the fact that food is available all year round in Jordan. Moreover, it was evident that families who maintain traditional practices such as food storage are likely to exhibit high levels of family identity. In contrast families that dismiss or partially abandon practices related to tradition are likely to exhibit low levels of family identity. Social Networks as a coping strategy: During unpredictable conditions, social networks play a significant role in maintaining family identity among group members (Brown and Perkins, 1992.). The experience of food sharing among group members is a rich and practical social experience. Literature suggests that social networks reduce the impact of hardship as displaced people share the same memory and reality (Pleck, 2000). The findings of the study show that social networks contribute to the maintenance of traditional food among members of a community. While refugees tend to seek for close social networks to help them cope with crisis and change (Tolsdorf, 1976), the findings of the study reveal that women Syrian refugees have high tendency to live within the same neighborhood for the purposes of sharing information on food offers, funding opportunities, and sources for traditional food ingredients. As a result, coping and maintenance of family identity is enhanced among family members. Research Question #2: What is the role of food consumption in shaping family identity for women refugees?The reconstruction of family identity can be attained using a set of measures as illustrated in Figure 1. These measures include: collective preparation of food, valuing traditional food and social capital.Collective food preparation as a strategy for reconstructing family identity: Literature shows that family practices are substantially influenced by changes in the family life span, such as changes in residency, work and family membership (Bennett, 1988). Past research highlighted that preparing food in a traditional style has a nostalgic or sentimental appeal referring to comfort food (Locher et al., 2005), which can be defined as any food consumed to induce positive emotions and is strongly associated social relationships (Locher, 2002). Preparing meals within the household enable the development of shared identity through shared practices (McIntosh et al., 2010). The findings declared that informants encountered many changes due to displacement such as separation from home and family gatherings. While celebrations generate a feeling of intimacy for surviving the difficult times (Denham, 2003), social networks were found to reduce the impact of hardship due to the mutuality in memory among displaced individuals. Women Syrian informants managed to successfully reconstruct their family identity through the collective preparation of traditional meals in groups of neighbors and family members during traditional and religious celebrations as a means to absorb social and economic shocks.Valuing traditional food as a reconstruction strategy for family identity: In past literature, women were in charge of holding the family together and transmitting traditions in order to add a sense of linkage with their family’s heritage (Pleck, 2000). Thus, displaced women were employing substantial efforts to transmit the values and traditions to the youth in the new home. The findings of this study reveal that displaced women play a key role in instilling loyalty for traditional food in younger generations. This result is evident in the attitude and food preferences of younger Syrian refugees.Economic Decision-making: While women and girls disproportionately affected by conflict due to a lack of access to essential services, as learnt from humanitarian crises in recent years (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010). The study shows that women Syrian refugees adjust their food consumption patterns according to the available resources. This constraint is dictated by the fact that each family has a limited budget. Consequently, decisions are made to minimize cost. Moreover, it was found that the informants set priorities and make clear distinction between necessities and luxuries. This is evident in the food choices made by women refugees as they tend to select low cost food, and plan for the purchase of basic needs each month (e.g. the first month would be for olive oil, the second month would be devoted for rice).The study concluded that food consumption plays a key role in the coping and the reconstruction of family identity where religion, tradition and socioeconomic security are of high importance. Religion was found to help recreate social reality through participating in group annual celebrations, which emphasizes a sense of belonging and shared identity. Also, social gatherings during religious celebrations contribute immensely to reconstruct family identity through joint preparations of food. In addition, traditional celebrations entail food storage as a key determinant in defining a coping strategy. Besides, the transfer of values including loyalty to traditional food in the younger generation is a common practice among women Syrian refugees. This measure has two dimensions, one is related to maintain cultural values, and the other is to instill cultural values in younger generations. Finally, it was found that social networks assist in supporting coping strategies through sharing of information (e.g. best food offers) within a neighborhood setting. Further, it was evident that the economic decision-making enables women Syrian refugees to reconstruct family identity through rationing expenses.Marketing Implications Connection to traditional food and the desire to sustain this connection among generations was visible among informants. Transferring values within the household can be relatively challenging due to separation from home. Nevertheless, it can be suggested that the involvement in trainings sessions that capitalize on traditional food and promoting it to individuals in the new home through the establishment through community based enterprise (cooperatives). Thus, this can be seen as a potential start up business for women Syrian refugees to participate in an informal economy to achieve economic independence through the production of traditional food. The study recommends to to validate and expand model proposed in this study by covering different geographical areas such as Turkey or Lebanon. This expansion can be used to investigate the Informal economy (corporations run by women for traditional food) since it was found that non-governmental organizations recruit Syrian women to cook traditional food in order to meet market demands. Further research can also be done on the impact of Syrian refugees to generate new startups and small or medium enterprises in the food industry (e.g. ice-cream, traditional meals).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML