-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Internal Medicine

p-ISSN: 2326-1064 e-ISSN: 2326-1072

2025; 13(1): 1-4

doi:10.5923/j.ijim.20251301.01

Received: May 19, 2025; Accepted: Jun. 9, 2025; Published: Jun. 13, 2025

Disseminated Tuberculosis and Esophageal Candidiasis Co-Infection: A Case Report

Rex K. Bonsu1, Tricia Bemah Adomako1, Nana A. B. Owusu Sekyere2, Semenyo Daddy1, Juliana N. Idun3, Selasi A. Daddy1, Maame Ama Boateng4, Edwin Akomaning5

1Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana

2Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Legon, Ghana Health Service

3Akai House Clinic, Accra, Ghana

4Department of Surgery, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana

5Department of Internal Medicine, The Community Hospital, Akim Oda, Ghana

Correspondence to: Rex K. Bonsu, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

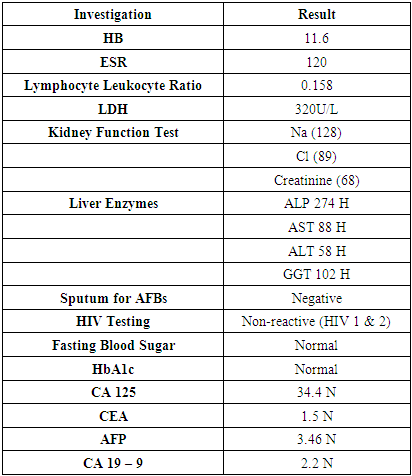

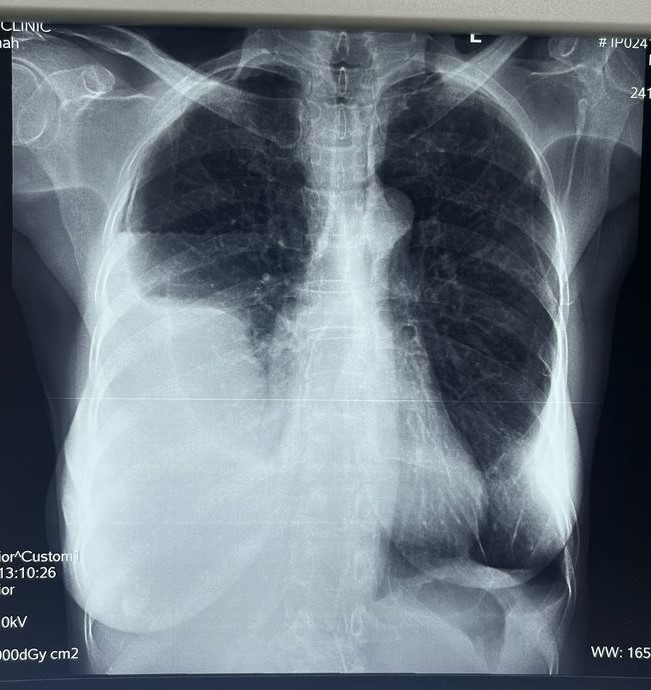

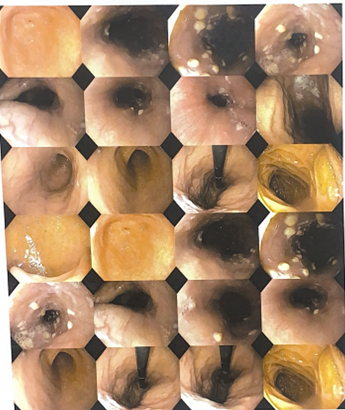

Introduction: Disseminated tuberculosis is an advanced form of tuberculosis that spreads from the lungs to multiple organs in the body. It is common in immunocompromised patients. Esophageal candidiasis is also an advanced form of candidiasis that commonly affects patients with immunosuppression, where the esophagus and stomach walls are involved. Both infections are common and have a fulminant course in the immunocompromised, but are extremely rare in immunocompetent patients. This report presents a unique case of disseminated tuberculosis and esophageal candidiasis in a patient with no underlying immunosuppression. Case Presentation: We present a 62-year-old Ghanaian female with no underlying immunosuppression, who presented to the out-patient department with non-specific symptoms (loss of appetite, dysphagia, early satiety, abdominal discomfort, and easy fatigability). She also had a sensation of food getting stuck in her throat. She reported significant weight loss and nausea. On examination, she was cachectic, mildly pale, and had white patches in her oral cavity. Her laboratory workup revealed mild anemia, hyponatremia, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and transaminitis. Chest -ray and CT scan revealed right pleural effusion with associated atelectasis, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed esophagogastric candidiasis. She was, therefore, diagnosed with disseminated tuberculosis and esophageal candidiasis and started on oral fluconazole for the candidiasis and the Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) regimen for tuberculosis. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks of starting antifungal therapy. She, however, developed transaminitis within a week of initiating antituberculous medication, which was halted till liver enzymes returned to baseline, and then she was reinitiated on them. Nutritional support therapy was given alongside. The pleural effusion resolved entirely following two months of antituberculous medication. Additionally, there was a significant improvement in her appetite, which is evidenced by an increase in her weight. Conclusions: Though more common and severe in immunocompromised patients, disseminated tuberculosis and esophageal candidiasis can also affect immunocompetent patients, though rarely. A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose this coinfection.

Keywords: Disseminated tuberculosis, Esophageal candidiasis, Pleural effusion, Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS)

Cite this paper: Rex K. Bonsu, Tricia Bemah Adomako, Nana A. B. Owusu Sekyere, Semenyo Daddy, Juliana N. Idun, Selasi A. Daddy, Maame Ama Boateng, Edwin Akomaning, Disseminated Tuberculosis and Esophageal Candidiasis Co-Infection: A Case Report, International Journal of Internal Medicine, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.5923/j.ijim.20251301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Disseminated tuberculosis (DTB) represents a serious manifestation of tuberculosis, characterized by the spread of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the pulmonary system to multiple organs within the body. Diagnosing disseminated tuberculosis can be challenging because its symptoms are often nonspecific [1-3]. Tuberculosis is often associated with decreased B and T cell immunity, NK cell dysfunction, and cytokine imbalances. Specifically, TB can lead to reduced numbers and impaired function of NK cells, while also affecting T cell responses and potentially altering cytokine production [4].Immunodeficiency can result from a wide range of causes, including congenital conditions, acquired infections such as HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, and malignancies. Notably, immunodeficiency may also be the initial manifestation of undiagnosed tumors [5].HIV is a major risk factor for disseminated TB, with up to 40% of HIV-positive individuals also presenting with disseminated TB [6]. In HIV, there are many infections, such as tuberculosis, because cellular immunity is reduced, leading to increased susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens. Co-infection with Candida species is more common in these individuals due to immune suppression [7-9]. In contrast, disseminated tuberculosis in immunocompetent individuals is rare, accounting for less than 5% of TB cases [1]. The simultaneous occurrence of Disseminated Tuberculosis and oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompetent patients is exceptionally rare and has been infrequently documented in the literature. Managing these co-infections is complex and requires careful balancing of treatments for both TB and candidiasis [10-12]. We present a case of disseminated tuberculosis with concurrent esophageal candidiasis in an immunocompetent patient, highlighting the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges faced.

2. Case Presentation

- A 62-year-old Ghanaian female presented to the General Outpatient Department (GOPD) with a 2-week history of loss of appetite, dysphagia, early satiety, abdominal discomfort, and easy fatigability. She described a sensation of food getting stuck in her throat during meals and feeling full after consuming only small portions of food. Additionally, she reported nausea but no vomiting and significant weight loss, which she attributed to anorexia. She also had an occasional dry cough but denied fever, night sweats, or dyspnea and had no known contact with anyone with a chronic cough. The patient has no history of smoking and is currently unemployed.During the physical examination, the patient appeared cachectic and exhibited mild pallor without signs of jaundice. An oral examination revealed white patches on the oral mucosa and tongue. Vital signs were generally within normal limits; however, the patient had an elevated pulse rate of 117 beats per minute. Chest examination indicated stony dullness to percussion over the right middle and lower lung zones, along with reduced tactile fremitus and vocal resonance. The intensity of breath sounds was also diminished. The respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 98-99% on room air. Abdominal examination showed mild tenderness in the epigastric region, while the neurological exam was unremarkable.A provisional diagnosis of possible TB pleuritis to rule out a malignant pleural effusion and oropharyngeal candidiasis was made. A chest x-ray (Figure 1) showed a homogeneous opacification of the lower two-thirds of the right hemithorax associated with a meniscus sign in the posterior costal pleural space and an air-fluid level in the anterior costal pleural space, suggesting a possible pleural effusion with an associated infection or inflammation. A chest CT scan revealed a large loculated right pleural effusion with associated atelectasis. There was linear atelectasis at the left lower lung base, and fibrotic changes were seen in the apical region of the left upper lobe with honeycombing. Small calcific densities, likely granulomas, were in the left lower and upper lung lobes. There was pleural thickening bilaterally, with left pleural calcifications.

| Figure 1. Chest X-ray |

| Figure 2. Upper GI Endoscopy images |

|

3. Discussion

- This case underscores the diagnostic challenges encountered in the management of disseminated tuberculosis, particularly in an immunocompetent patient, where both the diagnosis and presentation were atypical. The patient’s presentation lacked typical symptoms of fever and night sweats. Similarly, the presence of oral esophageal candidiasis in an immunocompetent individual is uncommon. The patient’s dysphagia and oral lesions prompted the diagnosis, but an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was required for definitive confirmation. The management of both conditions required a delicate and stepwise approach.This case highlights the importance of considering rare infectious conditions in immunocompetent patients, maintaining a high degree of clinical suspicion, and utilizing a multidisciplinary approach for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. A key limitation of this report is the absence of immunophenotyping, which could have provided valuable insights into the patient's immune status. This limits our ability to assess for underlying immunodeficiency or clarify the extent of immune system involvement in the clinical presentation.

4. Conclusions

- Co-infection of disseminated tuberculosis and oral esophageal candidiasis in immunocompetent individuals is rare and presents significant diagnostic challenges. High clinical suspicion is vital for improving diagnosis and treatment outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to thank the patient for consenting to the publication of this case report, the medical personnel involved in the patient's care, and my co-authors for their contributions.

Abbreviations

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML