-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Internal Medicine

p-ISSN: 2326-1064 e-ISSN: 2326-1072

2018; 7(2): 17-25

doi:10.5923/j.ijim.20180702.01

Safety and Efficacy of Sofosbuvir and Simeprevir Versus Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir in Treatment of Naïve Egyptian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection

Fathia Mohamed Abd EL Monem1, Wafaa Mohamed ELZefzafy1, Nessren Mohamed Bahaa EL Deen Mohamed1, Shiamaa Ibrahim Darwish2

1Tropical Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine of Girls, Al-Azhar Univerity

2Railway Hospital

Correspondence to: Nessren Mohamed Bahaa EL Deen Mohamed, Tropical Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine of Girls, Al-Azhar Univerity.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

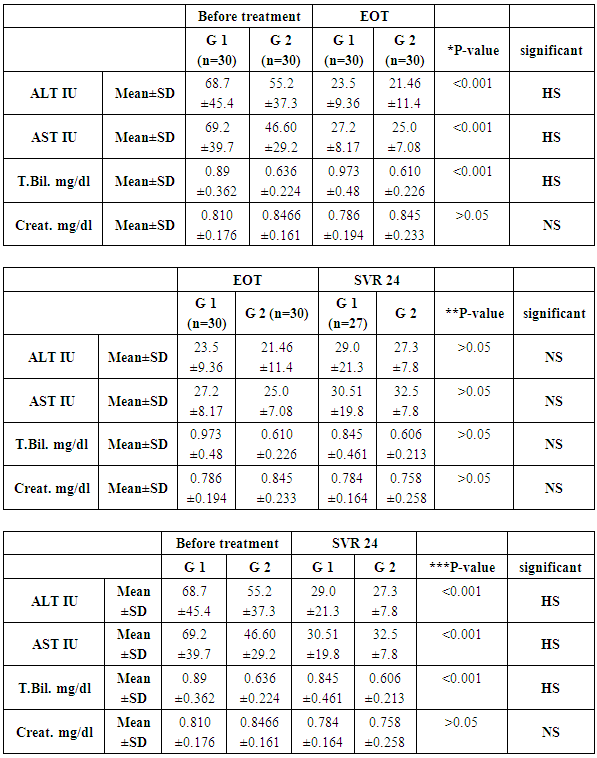

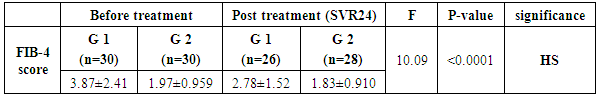

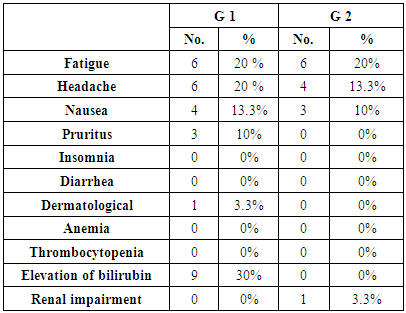

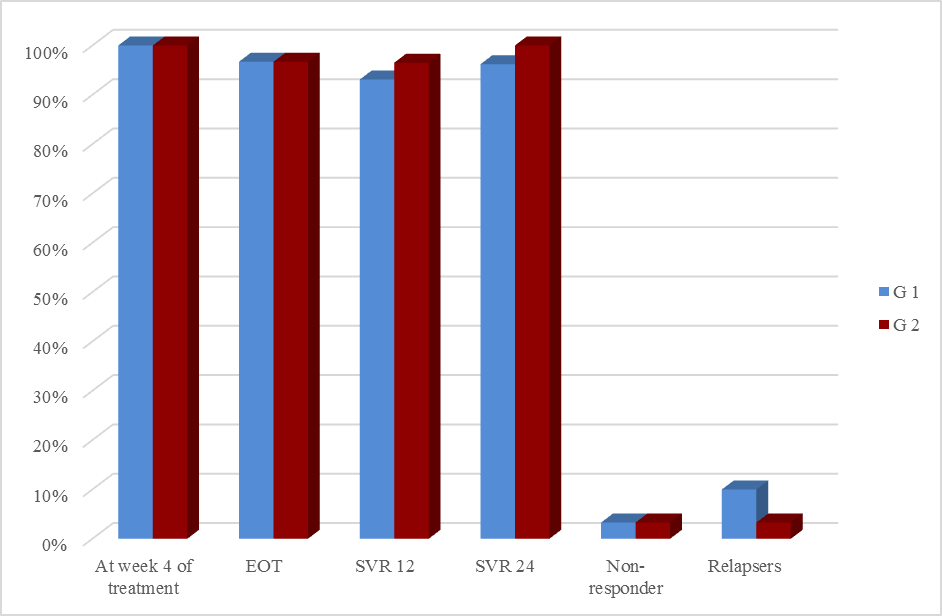

Hepatitis C infection considered to be one of the most important health problems in Egyp The treatment of chronic HCV was problematic due to lack of an effective and safe drugs. This study demonstrated that a virological response exceeding 90% in most genotypes. Aim: Study of safety and efficacy of combination between Sofosbuvir plus Simeprevir without ribavirin once daily versus combination of Sofosbuvir plus Daclatasvir without ribavirin once daily for 12 weeks in treatment of naive Egyptian patients with chronic HCV infection. Methods: this study included 60 patients divided into two groupsGroup I: Thirty patients received Sofosbuvir (SOF)400 mg plus Simeprevir(SMV) 150 mg once daily for 12 weeks. Group II: Thirty patients received Sofosbuvir 400 mg plus Daclatasvir 60 mg once daily for 12 weeks. All patients were subjected to detailed history taking and clinical examination. Assessment of liver fibrosis by FIB-4, Monitoring of treatment efficacy and endpoint at week 4, 8, 12 of treatment and a week at 12, 24 post treatment. Monitoring of treatment safety by complete liver profile, complete blood picture, creatinine each vist, and history taking about any side effects. Imaging by abdominal ultrasound. Results: There was no statistically significant difference in response rates to the combination of SOF/SMV regimen at week 4 of treatment (100%), at the end of treatment (96.7%) and post treatment at week 12(93.1%) and 24(96.2%) in comparison to the combination of SOF/DAC regimen at week 4 of treatment (100%), at the end of treatment (96.7%) and post treatment at week 12(96.5%) and 24(100%), but there was statistically significant increase in number of Relapsers who received SOF/SMV regimen (10%). There was highly statistically significant decrease in FIB-4 score in the responders of group-1 in comparison to the responders of group-2 before and post treatment (p<0.0001). The commonest adverse effects for both regimens were fatigue, headache and nausea, while with regimen SOF/SMV showed transient elevation of total bilirubin and cutaneous rash with prolonged exposure to sun. Conclusion: The oral regimen of SOF/SMV combination and SOF/DAC once daily for 12 weeks are an effective and well tolerated regimen and associated with high rate of sustained virological response (SVR) in naïve patients with different stages of fibrosis. The regimen of SOF/DAC has lower relapse rate than the regimen of SOF/SMV. The Fib-4 score was significantly decreased at week 24 post treatment in patients who received the regimen SOF/SMV.

Keywords: Sofsobuvir, Simeprevir, Daclatasvir, CHCV treatment

Cite this paper: Fathia Mohamed Abd EL Monem, Wafaa Mohamed ELZefzafy, Nessren Mohamed Bahaa EL Deen Mohamed, Shiamaa Ibrahim Darwish, Safety and Efficacy of Sofosbuvir and Simeprevir Versus Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir in Treatment of Naïve Egyptian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection, International Journal of Internal Medicine, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2018, pp. 17-25. doi: 10.5923/j.ijim.20180702.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Hepatitis C virus infection is the main cause of progressive liver diseases and a public health problem worldwide. Egypt is believed to have the highest rate of hepatitis C in the world (estimated at >10%) and most other African countries have prevalence rates ranging from 2% to >3% [1].Hepatitis C virus infection can present as acute or chronic hepatitis. Acute hepatitis usually is asymptomatic and rarely leads to hepatic failure. About 75–85% of people with acute infection develop chronic infection. The rate of spontaneous viral clearance in patients with chronic HCV is very low and chronic HCV develop cirrhosis with time [2].However, IFN-based treatments are accompanied by severe adverse effects, low tolerability and a suboptimal sustained virological response (SVR). Therefore, interferon-free regimens are needed. With the introduction of direct acting antiviral agents (DAAs), the treatment of HCV infections is evolving rapidly and interferon-free regimens are becoming a reality. DAAs have higher sustained virological response (SVR) rates, fewer side effects and decreased treatment therapy durations [3].Three major classes of DAA dominated the scenario at different stages of development and clinical practice: NS3/4A protease inhibitors, NS5B polymerase inhibitors and NS5A direct inhibitors. NS5B polymerase inhibitors are further categorized into two distinct groups: the nucleoside polymerase inhibitors (NIs) and the non-nucleoside polymerase inhibitors (NNIs). Their efficacies differ according to HCV genotypes, subtypes and they have a different barrier of resistance [4].The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) together updated guidelines for the treatment of HCV infection. It was recommended that the treatment of HCV infections should consist of several DAAs (elbasvir/grazoprevir, Ledipasvir, Sofosbuvir, Simeprevir, Daclatasvir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, dasabuvir, velpatasvir) alone or in combination with RBV [3].With the advent of new oral antiviral regimens, with better efficacy and tolerability and a shorter treatment duration, the number of patients that can be treated are expected to increase significantly and also the SVR rates will improve to approximately 95% or more [5].

2. Patients and Methods

- This was an observational prospective cohort study. It was conducted in outpatient’s clinic of gastroenterology and Hepatology of Railway hospital during the period from March 2016 till January 2017. The studied groups included 60 patients who were divided into two groups: Group I: Thirty patients received Sofosbuvir 400 mg plus Simeprevir 150 mg once daily for 12 weeks. Group II: Thirty patients received Sofosbuvir 400 mg plus Daclatasvir 60 mg once daily for 12 weeks.All the patients had to meet this criteria: × INCLUSION CRITERIA: Age 18-70 years old, HCV RNA positive, naïve patients and any Body Mass Index. × EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Age < 18 and > 70 years old, Total serum bilirubin ≥ 3 mg/dl, Serum albumin < 2.8 g/dl, INR ≥ 1 .7, Platelet count < 50.000/mm3. Ascites, Hepatic encephalopathy or history of hepatic encephalopathy, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Serum creatinine > 2 mg/dl, Pregnancy or inability to use effective contraception and Inadequately controlled diabetes mellitus.All patients were subjected to clinical assessment (before treatment and at 4,8,12 weeks, 12, 24 weeks after treatment) including detailed history of chronic liver disease especially bleeding tendency, ascites, jaundice, encephalopathy and symptoms of complication post treatment including fatigue, headache and pruritis.Laboratory investigations included complete blood picture, liver function tests including total bilirubin, ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, serum albumin and prothrombin time and concentration, fasting blood glucose level, blood urea and serum creatinine, hepatitis marker (HCV Ab and HBs Ag), quantitative PCR for HCV (12, 24 weeks post treatment), Alph-phetoprotien, TSH, ANA, assessment of fibrosis by FIB-4 pre and post treatment using FIB-4 =𝑨𝒈𝒆 (𝒚𝒆𝒂𝒓𝒔)×𝑨𝑺𝑻(𝑼𝑳)/𝑷𝒍𝒂𝒕𝒆𝒍𝒕𝒔 𝒄𝒐𝒖𝒏𝒕 (𝟏𝟎𝟗/𝒍)×√𝑨𝑳𝑻(𝑼𝑳) with cut-off <1.45 and cut-off >3.25 confirm advanced fibrosis.Virologic response was considered when HCV RNA is less than lower limit of detection (less than 15 IU) at the end treatment response (EOT) and post treatment at week 12 and 24. Ultrasound was repeated at week 24 post treatment for the responders. The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of the patients achieving a SVR at week 12 after the end of therapy. The second efficacy end point was the proportion of the patients achieving a SVR at week 24 after the end of therapy.

3. Statistical Analysis

- Data was collected, tabulated and statistical analyzed using IBM SPSS advanced statistics version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Numerical data were expressed as percentage, mean and standard deviation.Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Chi-square test was used to examine the relation between qualitative variables. Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison between two groups with quantitative data and non-parametric distribution. The comparison between 3 groups with quantitative normally distributed data was done by ANOVA test. P-value: A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant, A p-value < 0.001 was considered highly significant, A p-value >0.05 was considered non-significant

4. Results

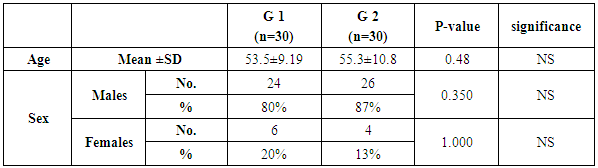

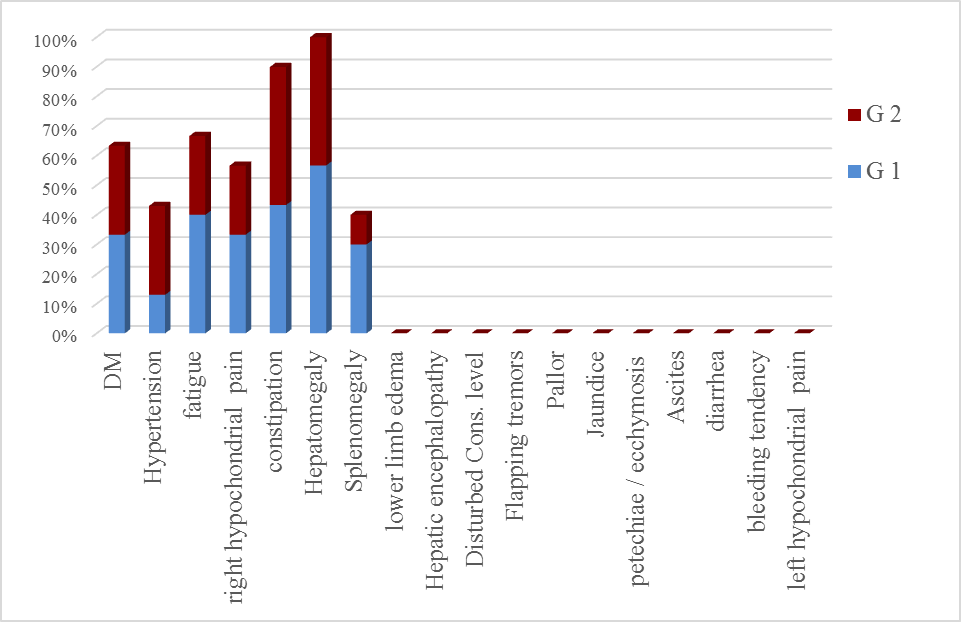

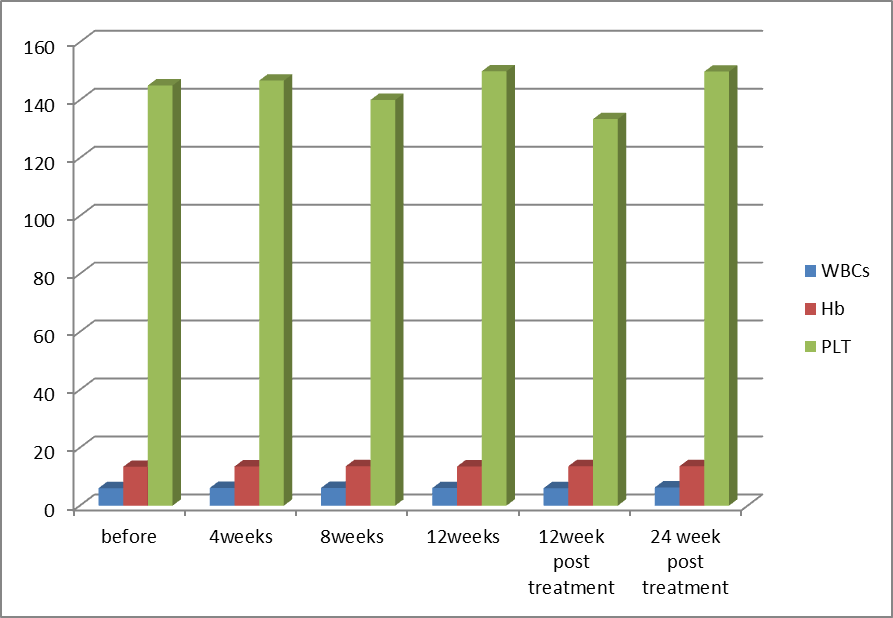

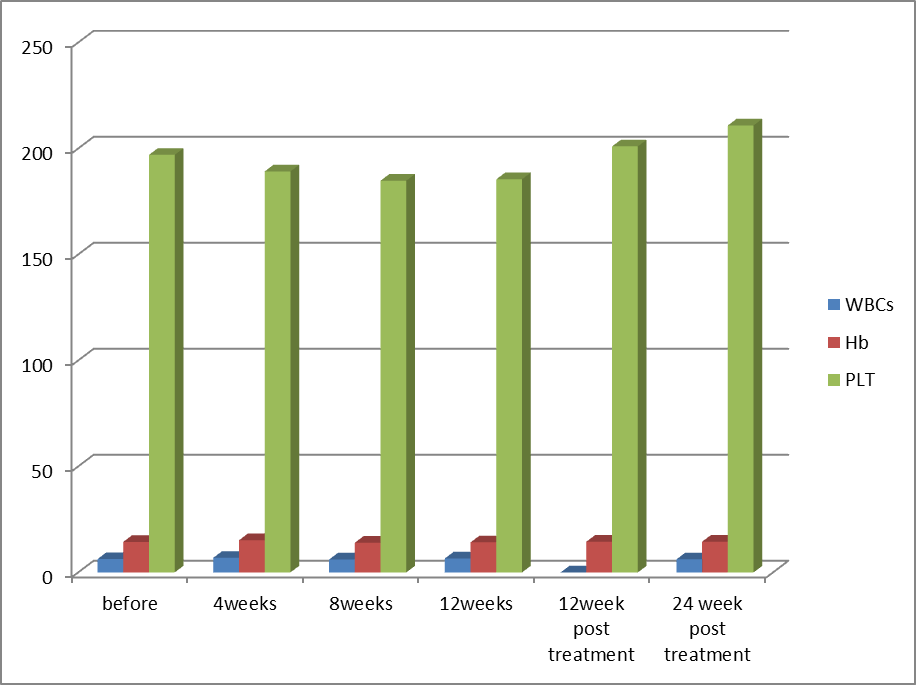

- This study was conducted on 60 patients. There were 50 male and 10 female patients with age ranging from 31 to 69 years. The results were summarized in table (1-2-3) and figure (1-2-3-4-5).

|

|

|

| Figure (1). Main history, symptoms & signs in the studied groups |

| Figure (2). Comparison of blood picture in Group-1 before receiving treatment, during treatment, at the end of treatment (EOT) and post treatment at week 12 and 24 (SVR12 and SVR24) |

| Figure (3). Comparison of blood picture in Group-2 before receiving treatment, during treatment, at the end of treatment (EOT) and post treatment at week 12 and 24 (SVR12 and SVR24) |

| Figure (4). Response rates to DAAs treatment among the studied groups |

5. Discussion

- In Egypt the overall prevalence of the anti-HCV antibodies and HCV RNA seropositivity is estimated at 14.7% and 9.8%, respectively [6]. While Amr et al., (2017) reported that The Demographic Health Survey (DHS) in 2015 showed 29% reduction in HCV RNA prevalence has been seen since 2008, which is largely attributable to the ageing of the group infected 40–50 years ago during the mass schistosomiasis treatment campaigns.The treatment of chronic HCV was problematic due to lack of an effective and safe drugs. In the past, treatment of chronic HCV infection worldwide was performed through many supportive line of treatment [8]. Since 1991, the interferon based therapy [interferon (INF) plus ribavirin (RBV)] was the main component of treatment options with low virological response not exceeding 50% [9]. In 2011, new medications named direct acting antivirals (DAA) were developed, which represents a major advancement in the treatment of HCV [10]. They inhibit specific stages in the HCV replication cycle through targeting the HCV polyprotein and its cleavage products [11]. The DAAs achieved a virological response exceeding 90% in most genotypes [12]. The DAAs had an improved safety profile, fewer side effects, better tolerability and shortened treatment duration with prolonged SVR. While first-generation DAAs were approved with Peg-IFN and ribavirin, but the current treatment regimens had moved away from Peg-IFN [13].In Egypt, the national committee for the control of viral hepatitis (NCCVH) started amass treatment program. The period from October 2014 till May 2015 the combination of SOF+RBV for 24 weeks and SOF+PEG+RBV for 12 weeks with SVR rate 78.4% and 94%, respectively. This followed by the combination of SOF+SMV with overall SVR12 rate 94%. Starting November 2015, generic SOF+DAC became the main line of therapy in the national program [14].Our aim was to study the safety and efficacy of combination of Sofosbuvir 400 mg plus Simeprevir 150 mg without ribavirin once daily for 12 weeks versus combination of Sofosbuvir 400 mg plus Daclatasvir 60 mg without ribavirin once daily for 12 weeks in treatment of naive Egyptian patients with chronic HCV infection. This was an observational prospective cohort study which carried out on 60 patients, never received treatment against HCV infection. The results of CBC before receiving the treatment in both groups, the P-value revealed that there were highly significant increase in red blood cell count and platelets count, significant increase in hemoglobin level in group-2 in comparison to group-1, although hemoglobin level was within normal range in both groups. Our findings were in agreement with Mei-Hua et al., (2015) [15] who reported that, the patients with chronic hepatitis C may had normal red blood cell count and haemoglobin level even may be found higher than the not infected patients in his trial. Mei-Hua et al., (2015) [15] reported that the patients with CHCV infection had thrombocytopenia. According to the liver biochemical profile of the studied groups before receiving the treatment, we found that there were highly statistically significant increase in the total bilirubin level in group-1 in comparison to group-2, although it was within normal range in both groups. Stephen and Timothy, (2006) [16] stated that serum bilirubin increased due to failure of liver cells to metabolize it. There were significant increase in level of AST and alpha-fetoprotein and decrease prothrombin concentration in group-1 in comparison to group-2. Our results were in agreement with Saito et al., (2015) [17] who reported that AST level was significantly higher in patients with significant fibrosis than those without it. Also Ke-Qin et al., (2004) [18] reported that the severity of hepatic fibrosis was associated with the significant elevation of serum AFP level. In our study there were statistically insignificant increase in ALT level and alkaline phosphatase and decrease in albumin level in group-1 in comparison to group-2, although the albumin level was within normal range in both groups. Our results were in agreement with Ohta et al., (2006) [19] who reported that significant negative correlation between fibrosis stage and albumin. Also were in agreement with Saito et al., (2015) [17] who reported that ALT level was higher in patients with significant fibrosis than those without it. On the other hand Alberti and Benvegnu, (2003) [20] who reported that some of the patients presented with liver damage can progress into liver fibrosis or liver cirrhosis despite normal or nearly normal ALT and AST levels. The findings of abdominal ultrasound at week 24 post treatment for the responders, showed no statistically significant difference in comparison to the findings before receiving treatment. In our study there were highly significant decrease in the level of ALT and AST at EOT and SVR24 in both groups. Our results were in agreement with Hanno et al., (2016) [21] who found that in the real life study on Egyptian patients a significant improvement of liver enzymes values after treatment by SOF/SMV regimen. Damian, (2017) [22] who mentioned that the liver enzymes quickly normalised during therapy of CHCV by SOF/DAC regimen indicating that hepatic inflammation had reduced. By using FIB-4 score for assessing the degree of liver fibrosis in our patients, we found that group-1 had 13 patients with F0-F2 (43.3%) and had 17 patients with F3-F4 (56.6%). While group-2 had 26 patients with F0-F2 (86.6%) and had 4 patients with F3-F4 (13.3%). This was matched with the results of the laboratory investigations and the findings of ultrasound. The group-1 had more patients with advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) in comparison to the patients of group-2 and this explained by EL etreby et al., (2017) [23] who mentioned that the National Committee for the Control of Viral Hepatitis (NCCVH) in Egypt had given the a priority in treatment to the patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, in spite of significant lower SVR compared with non-cirrhotics. All 30 patients in group-1 completed the treatment with Simeprevir 150 mg plus Sofosbuvir 400 mg once daily without RBV for 12 weeks, the end of treatment (EOT) success rate was 96.7%. This result was in agreement with the real life study that evaluated by EL etreby et al., (2017) [23] on chronic Egyptian HCV. genotype-4 infected patients, who received SOF/SMV regimen with end of treatment (EOT) succession rate 97.6%. As regard to the primary end point (SVR12) rate for the patients who received SOF/SMV regimen was 93.1%. These result was in agreement with the published results of Phase IIa OSIRIS clinical trial, at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) in November, 2015. This study was evaluated by EL Raziky et al., (2015) [24] who investigate once daily SOF/SMV combination in HCV genotype-4 infected patients and demonstrated that the SVR12 rate was up to 100% in patients treated for 12 weeks regardless of fibrosis stage and treatment history. Our result was also in agreement with trial evaluated by Willemse et al., (2016) [25] on patients with genotype-4 HCV infected patients with advanced fibrosis, the SVR12 rate was 92% after 12 weeks treatment with SOF/SMV regimen. The combination of SOF/SMV in our study showed higher rate of SVR12 (93.1%) compared to the TRIO real life study on HCV genotype-1 infected patients in which SVR12 rate was 88% in treatment of naïve and non-cirrhotic patients [26]. Eric et al., (2016) [27] Suggested that HCV genotype-4 may be more susceptible to Simeprevir than genotype-1. As regard to the second end point (SVR24) rate was 96.2%. Our result was in agreement with the real life study evaluated by Hanno et al., (2016) [21] who reported that the SVR24 rates was 96.6%.All 30 patients in group-2 completed the treatment by the combination of Sofosbuvir 400 mg plus Daclatasvir 60 mg once daily without RBV for 12 weeks, the end of treatment succession rate (EOT) was 96.7%. The same result was obtained by Omar et al., (2017) [14]. The study evaluated by Mark et al., (2014) [28] on HCV genotype-1 infected patients received the combination of SOF/DAC for 12 weeks, they reported that the end of treatment (EOT) success rate was 100%. As regard to the primary end point (SVR12) rate for our patients who received SOF/DAC regimen was 96.5%. Our result was in agreement with the studies evaluated by Omar et al., (2017)) [14] on Egyptian HCV genotype-4 infected patients, they reported that the SVR12 rate was 95.4% and 96.6%, respectively. Also in the study evaluated by Hezode et al., (2016) [29] on the genotype 4, 5 and 6 HCV infected patients, they found the SVR12 rate for genotype-4 was 91%. In a study evaluated by Pol et al., (2017) [30] on naïve non-cirrhotic HCV genotype-1 infected patients, were received the combination of SOF/DAC for 12 weeks and the SVR12 rate was 92%. They found that the SVR rates did not significantly differ with (98%) or without ribavirin (94%). As regard to the second end point (SVR24 rate) for the patients who received the combination of SOF/DAC was 100%. In the studies evaluated by Mark et al., [28] on naïve genotype-1 infected patients who received the same regimen, they found that the SVR24 rate was 95% and 89%, respectively. In our study we found that no statistically significant difference in response rate to the combination of SOF/SMV and the combination of SOF/DAC at week 4 of treatment, at the end of treatment (EOT) and at week 12 and 24 post treatment (SVR12 and SVR24). As regard to group-1 (SOF/SMV) no patient experienced viral breakthrough and only one patient not respond to treatment (3.3%), but there were relapse in 3 patients (10%), two of them were relapsed at week 12 post treatment and one of them was relapsed at week 24 post treatment. Our results were in agreement with the study evaluated by Hanno et al., (2016) 21on HCV genotype-4 Egyptian patients, who reported that no patient experienced viral breakthrough. The relapse rate (10%) in our study was higher than the relapse rate in EL etreby et al., (2017) [23] study (2%), this may be due to the limited number of our patients. While our relapse rate was lower than the observed in other IFN free based combinations as Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in trial evaluated by Ruane et al., (2015) [31] who reported that the relapse rate was 18.3%. As regard to group-2 (SOF/DAC) no patient experienced viral breakthrough and only one patient not respond to the treatment (3.3%), one patient relapsed (3.3%) at 12 weeks post treatment. Also Hezode et al., (2016) [29] reported that the relapse rate was 5.4% in their study. As regarding to the FIB-4 score, there was highly significant decrease in FIB-4 score in the responders of group-1 who received SOF/SMV regimen in comparison to the responders of group-2 who received SOF/DAC regimen. In the study evaluated by Damian, (2017) [22] he reported that, there was decrease in the fibrosis scores from baseline after receiving DAAs. Our study revealed that the combination of SOF/SMV was well tolerated, with no adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment and no deaths occurred. As regard to the complications that detected in the patients who received SOF/SMV regimen were transient elevation in total bilirubin in 9 patients (30%), fatigue in 6 patients (20%) headache in 6 patients (20%), nausea in 4 patients (13.3%) cutaneous rash was present in one patient (3.3%). These findings were in agreement with Hanno et al., (2016) [21]. In SONET study evaluated by Imtiaz et al., (2017) [32] they found that the patients who received SOF/SMV regimen presented with headache in (13.4%), nausea in (11.7%), fatigue in (11%) and cutaneous rash in (3.8%). Other adverse effects occurred in this study were insomnia in (5.2%), abdominal pain in (3.4%), diarrhea in (3.4%), dyspnoea in (2.7%) and anaemia in (2.4%) in contrast with our study.In contrast with our study EL etreby et al., (2017) [23] they found adverse effect occurred as liver cell failure with resultant mortality occurred in (0.37%), haematological complications in (3.09%), ischaemic heart disease in (1.03%) and angiomatous oedema (Drug hypersensitivity) in (1.03%). Our study revealed that the combination of SOF/DAC was well tolerated, with no adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment, no deaths occurred. As regard to the complications that detected in the patients who received SOF/DAC regimen were fatigue in 6 patients (20%), headache in 4 patients (13.3%), nausea in 3 patients (10%) and one patient (3.3%) had mild elevation of renal function. Our findings were in agreement with the studies evaluated by David et al., (2015) [33] and Hezode et al., (2015) [29] who reported that no adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment and no deaths occurred, the most common adverse effects occurred were fatigue, headache and nausea. Omar et al., (2017) [14] found in their study acute renal injury in 1 patient as adverse effects. While Tania et al., (2016) [34] who reported that the commonest adverse effects were fatigue, headache, arthralgia and gastrointestinal events. Also in contrast to our findings, the study evaluated by Omar et al., (2017) on Egyptian HCV genotype-4 infected patients, they found adverse effects that led to discontinuation of the therapy as haematological (4 patients), decompensation and/or ascites (3 patients), hepatocellular carcinoma (2 patients) and Status asthmaticus (1 patient).

6. Conclusions

- The oral regimen of SOF/SMV combination and SOF/DAC once daily for 12 weeks are an effective and well tolerated regimen and associated with high rate of sustained virological response (SVR) in naïve patients with different stages of fibrosis. The regimen of SOF/DAC has lower relapse rate than the regimen of SOF/SMV. The Fib-4 score was significantly decreased at week 24 post treatment in patients who received the regimen SOF/SMV.

7. Recommendations

- Further studies on a large scale of naïve non-cirrhotic HCV infected patients, on patients have HBV co-infection with HCV. Pre and post treatment evaluation of blood sugar lipid profile and cardiac condition.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML