-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Internal Medicine

p-ISSN: 2326-1064 e-ISSN: 2326-1072

2014; 3(1): 9-12

doi:10.5923/j.ijim.20140301.02

Prevalence of False Negative Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Hemodialysis Patients

Farag Salama Elsayed1, Qasem Anass Ahmed1, Elsayed Mohamed1, Fakhr Ahmed Elsadek2, Elsolamy Ahmed Said3

1Nephrology unit, Internal Medicine department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, 44519, Egypt

2Microbiology department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, 44519, Egypt

3Clinical Pathology department, Central Clinical laboratory, 112765, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Farag Salama Elsayed, Nephrology unit, Internal Medicine department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, 44519, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection in hemodialysis (HD) patients is persistently greater than in the general population. Difference in prevalence rates of HCV infection in HD patients has been reported from different regions of Saudi Arabia. Despite the precautions taken on blood products, HCV transmission is still being observed among HD patients. In order to reduce the anti-HCV false-negative results; HCV RNA testing for blood screening has been implanted. Ninety eight HCV negative HD patients were recruited from two HD units for this study. Routine screening for anti-HCV, HBs Ag and anti-HIV, in addition to HCV RNA quantitative PCR were done for all HD patients. Among 98 HD patients with anti-HCV-negative, 17 (17.3%) were HCV-RNA positive by PCR, with viremia load ranged from 2000 to 5,507,245 IU/ml. Significant difference between False negative HCV patients and True negative HCV patients regarding duration of hemodialysis was noted. The current status of the HCV infection and the frequency of the false negative HCV infection in HD population were determined with recommendation of implanting HCV RNA screening as mandatory testing in HD patients.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, Hepatitis C infection

Cite this paper: Farag Salama Elsayed, Qasem Anass Ahmed, Elsayed Mohamed, Fakhr Ahmed Elsadek, Elsolamy Ahmed Said, Prevalence of False Negative Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Hemodialysis Patients, International Journal of Internal Medicine, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 9-12. doi: 10.5923/j.ijim.20140301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore the impact of HCV infection as a major public health problem affecting around 170 million people worldwide. [1]The prevalence of HCV infection in HD patients is persistently greater than in the general population [2] predominantly in the Mediterranean and developing countries of the Middle and Far East. [3]Difference in prevalence rates of HCV infection in HD patients has been reported from different regions of Saudi Arabia: 34.8% to 53.7% in the central province [4, 5] 46.5% in the eastern province [6] and 45.5% in the southern province [7]. In a multi-center study involving 22 centers in Saudi Arabia, prevalence rates of HCV infection in hemodialysis units varies between 14.5% and 94.7% [8]. Despite strict precautions taken on blood products, HCV transmission is still being observed among HD patients. Prolonged vascular exposure puts HD patients at increased risk of infection with blood-borne pathogens, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), HCV and HIV, from contaminated devices, equipment and supplies, environmental surfaces or attending personnel [6].Several studies have reported nosocomial transmission of HCV in HD units contributable to breaches in infection control practice or contamination of dialysis machines. [7-9]Diagnosis of HCV infection is usually based on detection of anti-HCV antibody. This method has several pitfalls, including the window period in which antibodies are still undetected and the inability to differentiate between true infected patients and those who have recovered from infection. [9]In order to reduce the anti-HCV false-negative results, HCV RNA testing for blood screening has been implanted, as the false-negative rate of anti-HCV is many times higher among HD patients (up to 12%) [10].Therefore, we attempted in this study to detect the frequency of false negative HCV infection by Nucleic Acid Amplification Technology (NAT) testing in anti-HCV negative HD patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

- A cross-sectional study was done in December 2012 at HD units of Jeddah and Yanbu General Hospitals, Saudi Arabia. A total of 98 patients (49 men, 49 women) undergoing HD were enrolled. They were (63±13) years old (range 30–86 years old), and the dialysis duration was (44±12) months (range 8–120 months). The primary diseases of these HD patients were chronic glomerulonephritis (8 cases), diabetic renal disease (27 cases), Lupus Nephritis (4 cases), hypertensive nephropathy (23 cases), polycystic kidney disease (2 cases), obstructive uropathy (5 cases), graft dysfunction (5 cases) and unidentified (24 cases).Hemodialysis was performed three times a week, four hours per session, using single-used low-flux polysulfone dialyzers with a membrane surface area of 1.3 m2 – 1.6 m2. The study was approved by the ethics committee of both hospitals, conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.All dialysis units are using a Citrosteril method of disinfection. Universal precautions to avoid infection as a hand wash, change of gloves, face shields, and waterproof gowns among patients while performing HD are followed by staff members. Trays are changed regularly between patients. A single blood pressure cuffs are fixed for each machine and reusable by patients using the same machine. Multi-dose medications are not allowed; heparin, vitamin D, and erythropoietin are used in a single-dose form. Dedicated machines and isolated areas are used for anti-HCV positive patients, no dialyser reuse were done in both units.

2.2. Laboratory Measurements

- Blood samples were collected from patients before dialysis into two tubes: the first tube contains an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) where the plasma was separated rapidly and stored at -70℃ to be used for HCV RNA testing and the other tube was a plain tube used to separate sera to be used for liver biochemical tests and enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent (ELISA) antibody tests.Routine screening for anti-HCV, HBsAg and anti-HIV was carried out by Monolisa ™ HCV Ag-Ab ULTRA assay, Monolisa ™ HBs Ag ULTRA assay and Genie Fast HIV 1/2 assay respectively (BIO-RAD; New Ash Green, UK). ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, serum albumin, and serum bilirubin were performed using Bayer Advia 2400 clinical chemistry system. Tests were performed and interpreted strictly according to the manufacturer's instructions.Viral RNA was extracted using the viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the protocol provided. The first strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized. Initial denaturation was performed at 95℃ for 5 min. Polymerase chain reaction amplification was carried out at 94℃ for 1 min, 57℃ for 1 min, and 72℃ for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles and final extension at 72℃ for 7 min. The primer sequences are as follows: forward—5′CGCGCGACTAGGAAGACTTC3′ and reverse—5′ACCCTCGTTTCCGTACAGAG 3′.Absolute quantification of HCV RNA was done using ABI 7300 Prism® (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, USA). HCV RNA viral load was categorized as low (<100.000 IU/ml), moderate (100.000–1000.000 IU/ ml), or high (>1000.000 IU/ml).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

- Results for continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Counts and percentages were used for the description of the categorical variables. Comparisons among groups were made with Student's T- test for continuous normal-distributed variables and with chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. A P-value less than .05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 19.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, III, USA).

3. Result

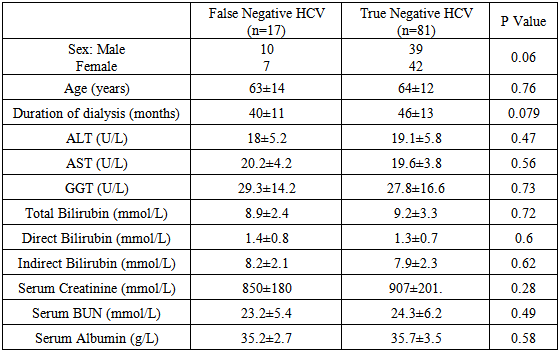

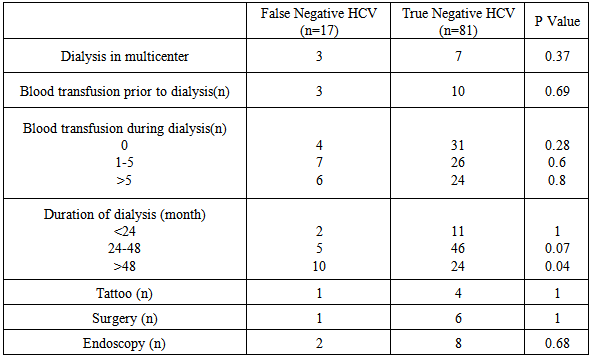

- Demographic data and laboratory investigations of false negative HCV and True negative HCV patients are highlighted in Table 1.

|

|

4. Discussion

- HCV infection is still a common complication in HD patients. The global anti-HCV prevalence is up to 91% [11] because of frequent past blood transfusions and the duration of dialysis. [12, 13] However, the prevalence of HCV infection among HD patients varies between countries and between dialysis units within a single country.Our study showed a relative high frequency of false negative HCV infection in HD patients despite the adherence to universal infection control precautions and the dedicated machine use for anti-HCV-positive patients. The explanation for this finding might result from the decreased sensitivity of commercially used methods for anti-HCV testing and presence of the window period between infection and seroconversion, even after introduction of third-generation anti-HCV ELISA. [14]Furthermore, uremic patients have immune dysfunction; this may reduce the ability to elicit an antibody response against HCV. A similar lack of immune response is described in uremic patients after HBV vaccination, and in HIV-positive individuals. [15]Our study showed a wide range of firearm load, the reason for this is not clear, but it might be explained by several mechanisms. First, HD procedures lowers HCV RNA levels as the HCV RNA particle is entrapped and destroyed onto the dialyzers’ membrane surface [16, 17]. Second, prolonged and marked production of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) during HD sessions suggesting a beneficial effect of HGF to hepatocyte proliferation and accelerated liver repair. [18] Lastly, marked increase of Interferin alpha (IFN α) levels after dialysis when using both cellulose and synthetic membranes, this increase in endogenous IFN α could contribute to a reduction in viremia in HCV infected patients on maintenance dialysis. [19]It is interesting to note that 60% (10 of 17 cases) of detecting false negative HCV patients were maintained in HD more than 48 months, this finding increase the possibility of HCV infection with prolonged duration of HD. The present findings seem to be consistent with Thongsawat et al. [20] On the contrary, Li and Wang [21] showed that there was no significant association between HD duration and HCV infection, with a significant correlation between the history of blood transfusions and kidney transplantation and the prevalence of HCV infection.Finally, this study has some limitations need to be considered. First, its cross-sectional design in which diagnosis of false negative HCV infection has been depended on one blood test, as there was a lack of follow up Anti HCV seroconversion. Second, limited sample size enrolled in our study, so the relationship between false negative HCV infection and hemodialysis associated risk factors should be further examined in a prospective design with a larger number of subjects.In conclusion, this study helps in determining the current status of HCV infection and the frequency of the false negative HCV infections in our HD patients. The screening of the HD patients for serum HCV RNA adds to the cost, but it is definitely useful in reducing the risk of hepatitis among HD patients.

Abbreviations

- HCV, Hepatitis C virus, HD, Hemodialysis, HBs Ag, Hepatitis B s antigen, HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus, PCR, Polymerase chain reaction

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML